Millennium Actress Review: Satoshi Kon answered, “Really, there’s nothing dumber than asking a painter why he painted an apple instead of pear. People have very fixed ideas about anime.” The question was, “So why not live-action?”. Anime as a genre is not just for the inner-child within you but can carry powerful themes to bewitch the mature audience. A cogent argument to prove that point is the films of Satoshi Kon, the singular anime film-maker whose virtuoso display of visual agility has no precedence in animation or live-action film-making. Kon’s main body of work contains four feature-films and the mini-series Paranoia Agent. He died of terminal pancreatic cancer at the age of 46. Yet his profound, revolutionary, and beautiful works of cinema – replete with visual and cerebral delight – I hope is celebrated and rediscovered by generations of cinephiles.

Kon’s debut feature Perfect Blue (1997) delivered an innovative and hard-hitting commentary on media representation and overwhelmingly toxic fandom. Kon’s sophomore effort Millennium Actress ( Sennen joyu, 2001) serves as an antithesis to Perfect Blue, where the relationship between an artist and a fan is presented in a more positive light. Kon is said to have called the two films as “both sides of the same coin”.

While trying to explain the plot-points of Kon’s cinema, one would inevitably fail to convey the overpowering visual experience. On the outset, Millennium Actress’ story, for a lack of better, sounds simple. A small-time video producer Genya Tachiban takes his unenthused cameraman to interview a former movie star named Chiyoko Fujiwara who now lives a solitary life with minimum social contact. Fujiwara takes a dive into her old memories, reminiscing about wartime, post-war existence and her lost love, the chase for which turned her into the great artist she was.

Related to Millennium Actress – Satoshi Kon: One of the most influential filmmakers of his Time

Though it sounds melodramatic or tragic, once the story takes off – brimming with Kon’s trademark transitions and intercutting – we are totally pulled into the action. Kon and his co-writer Sadayaki Murai’s basic premise – the effort taken to interview an old movie-star long disappeared from public life – is reminiscent of a similar situation involving Setsuko Hara, the phenomenal actress who is best known for her collaboration with director Yasujiro Ozu. She retired at the age of 43 and lived as a hermit for the next half-century (until her death in 2015).

Middle-aged Genya, a long-time fan of Chiyoko, and his cameraman initially stand as the passive witnesses in the actress’ memories. When youthful Chiyoko recalls her first casting offer or when she accidentally encounters a young artist on the run, the aging actress’s living room space jumps to the reconstructed space of her memories with Genya enthralled by the opportunity to ‘observe’ everything from the sidelines. The cameraman is not much familiar with the actress’s works or her life, and he is more of a cynical observer, unwittingly caught in the tempestuous cloud of Chiyoko’s memories.

Chiyoko instantly falls in love with the aforementioned young artist, who is pursued by the wartime authorities. She offers him shelter for a day and when he successfully escapes to Manchuria, Chiyoko takes up the acting opportunity and sails off to Manchuria. The young artist leaves a mysterious key with Chiyoko. Although the chase becomes increasingly futile, Chiyoko’s determination turns her into a bankable post-war movie star. The characteristic Kon maneuvers begin when the actress’s memory about the search blends in with the images of movies she performed. Her ‘real’ and ‘cinematic’ memories get increasingly blurred as Genya, often in the ‘cinematic’ memories, takes over the role of the savior. The young Genya has worked in the studios when Chiyoko was propelled into the limelight and has always harbored a crush on the actress.

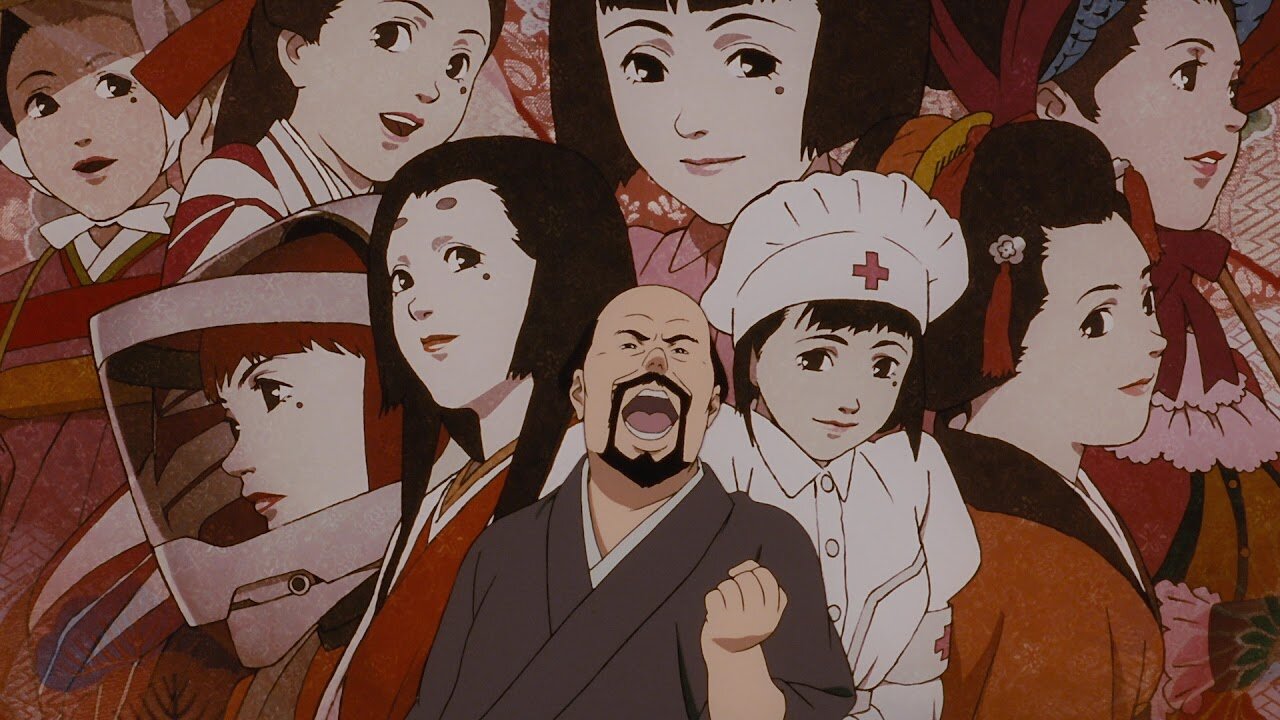

Hence, it’s no wonder he embraces the opportunity to occupy an active role in her memories. From wearing an out-dated samurai suit to being a truck-driver, Genya the fanboy enjoys the thrill of this roller-coaster ride. Throughout this phase in the narrative, Kon playfully restages pivotal moments from classic cinema, ranging from Akira Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood, Ozu’s Tokyo Story to Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. In fact, the enduring theme in the films of Chiyoko Fujiwara happens to be the pursuit of love. The beauty that lies in the transitions between Chiyoko’s reality and her on-set action or the kaleidoscopic profusion of summoned memories is absolutely indescribable. While Kon’s investigation of reality in Perfect Blue provoked a sense of anxiety, Millennium Actress reaches for the opposite mood: excitement and elation.

Also by Satoshi Kon- Tokyo Godfathers [2003]: A Richly-Textured Christmas Dramedy

Millennium Actress can sound so conventional, but once Kon starts interweaving reality and fiction, his distinctive abilities come into focus, and the excessive care he has taken to craft the minutiae can really be intimidating for the perceptive viewers. Chiyoko’s recollections brilliantly showcase the relationship between memory and desire. The feeling we get from Chiyoko’s tumultuous and warmhearted recollections of professional and personal life is that this is her way of keeping the desire alive, even though the chase has become futile. As she states, “life is the thrill of the chase, even if you’re chasing a shadow.”

On a broader sense, ‘the thrill of the chase’ can be taken as an interpretation of the very nature of film-making. As Actress Mami Koyama, one of the three who lends her voice to Chiyoko Fujiwara says that: “…the shadow that Chiyoko pursues is perhaps Cinema itself for the director. I think it’s a film with very strong feelings toward film-making”.

Nevertheless, I feel that between these two, Perfect Blue is a better work, probably because its critique on the media/pop-icon culture offered a rich subtext compared to this freewheeling chase of a phantom lover. Millennium Actress undoubtedly pays a poignant tribute to the power of cinema and the enduring relevance of an artist. But Perfect Blue through its complex study of obsession, identity, and reality offered much deeper layers of meaning. While Kon was promoting this productive and positive side of the idol-fan relationship [in Millennium Actress] through an intrinsically predictable yet visually exhilarating narrative, I was nagged by the lack of serious character development. The film, to an extent, got better in the re-watch once I submitted myself to Satoshi Kon’s dynamic, out-of-the-box visual elements.

★★★★

Trailer

Millennium Actress (2001) Links: IMDb, Rotten Tomatoes, Letterboxd

![Atrangi Re [2021] Review: A Bland and Problematic Film Discussing Indian View of Mental Health](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Atrangi-Re-Movie-Review-2-768x464.png)

![Personal Shopper [2016] – An Imaginative Examination of Grief and Personal Identity](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Personal-Shopper-Kristen-Stewart-768x442.jpg)