Cinema in India has long mirrored the country’s social hierarchies, often reinforcing dominant-caste narratives while rendering Dalit experiences invisible. Yet, scattered across the decades are films that dared to challenge caste orthodoxy, some subtly, others with unflinching rage. In a country where caste continues to shape social structures and individual destinies, films that confront caste-based discrimination and engage with Ambedkarite politics occupy a crucial space in the cultural discourse. These films do more than tell stories, they challenge hierarchies, provoke dialogue, and assert the humanity and dignity of those historically marginalized.

At its core, Ambedkarite politics calls for the annihilation of caste, not just through legal reform but through social transformation, education, and self-respect. It rejects caste-based hierarchies and ritualistic practices that uphold Brahmanical dominance, advocating instead for equality, dignity, and justice rooted in constitutional rights and rational thought. Dr. B.R. Ambedkar’s radical vision of social justice, equality, and the annihilation of caste has inspired generations of thinkers, activists, and artists.

In recent years, a growing body of cinematic work has begun to foreground Ambedkarite perspectives, moving beyond tokenistic representation to interrogate the systemic violence and everyday humiliations that caste engenders. Through social realism, biographical storytelling, and politically charged narratives, these films confront audiences with the caste question, an issue that remains deeply entrenched and critically relevant in Indian society.

The lineage of anti-caste and Ambedkarite cinema has evolved from cautious reformism to radical assertion. “Achhut Kanya” (1936), directed by Franz Osten and produced by Bombay Talkies, is often cited as one of the earliest films to address untouchability. It tells the story of a romantic relationship between an upper-caste boy and a Dalit girl, leading to tragic consequences. While limited by its Gandhian moralism and savarna gaze, the film initiated a conversation about caste injustice in a mainstream idiom.

“Sujata” (1959), directed by Bimal Roy, continued this trend of upper-caste liberal humanism. Adapted from Subodh Ghosh’s short story, it centers on a Dalit girl raised in a Brahmin household. While the film advocates for compassion and social inclusion, it still locates resolution in the moral evolution of the upper-caste family. Caste is portrayed as a moral failing rather than a structural system of oppression, a significant distinction from Ambedkarite thought.

It wasn’t until “Bandit Queen” (1994), based on the life of Phoolan Devi, that anti-caste cinema took a sharp, unsentimental turn. Directed by Shekhar Kapur, the film portrays caste not just as a background detail but as the crucible of violence and resistance. Phoolan’s transformation from a violated girl to a rebel dacoit is framed within the intersecting brutalities of caste, patriarchy, and poverty. While the film courted controversy for its representation of sexual violence, it also marked a pivotal moment in Indian cinema by making caste-based atrocity and rebellion visible, raw, and unapologetic.

Over time, this lineage grew more self-aware and assertive. Filmmakers like Nagraj Manjule, Pa. Ranjith, and Mari Selvaraj began to craft films rooted directly in Ambedkarite consciousness, telling stories not about Dalits but by and for them, reclaiming voice, gaze, and agency. From the reformist pathos of “Achhut Kanya” to the militant aesthetics of “Papilio Buddha” and the prideful assertion in “Kaala,” the journey of anti-caste cinema traces the long arc of struggle, from muted suffering to political resistance, from invisibility to self-representation.

On the occasion of Dr. B.R. Ambedkar’s birth anniversary, this list brings together films that echo his vision, challenge caste oppression, and carry forward the radical legacy of his emancipatory politics. These are films that align with or are informed by Ambedkarite thought, offering powerful critiques of the status quo and envisioning alternative futures grounded in justice and dignity.

15. Papilio Buddha (2013)

“Papilio Buddha,” directed by Jayan K. Cherian, is a searing and unapologetically radical film that situates caste oppression within the intersecting terrains of land dispossession, environmental destruction, queer identity, and Ambedkarite politics. Set in the Western Ghats of Kerala, the film centres on a group of landless Dalits, many of whom are followers of B.R. Ambedkar and Buddhism, who resist both the violence of the state and the indifference of the environmentalist upper-caste elite.

What distinguishes “Papilio Buddha” is its overt engagement with Ambedkarite ideology, not merely in reference but as praxis. The characters read Ambedkar, revere his legacy, and invoke his thoughts as a guide for radical socio-political transformation. The film critiques Gandhian paternalism, exposes the hypocrisy of caste in so-called progressive Kerala, and lays bare the brutal mechanisms of state repression. It also boldly foregrounds queer Dalit subjectivity, refusing to compartmentalize identity politics and instead weaving together caste, gender, sexuality, and land as mutually constitutive struggles.

Visually and thematically, the film disrupts narrative conventions. The use of stark imagery – such as self-immolation, forced evictions, and the destruction of Ambedkar statues – serves as a visceral indictment of caste violence and state complicity. Importantly, the title itself, referencing the endangered butterfly species Papilio buddha, becomes a potent metaphor for the Dalit condition – beautiful, hunted, and ignored by mainstream ecology and culture alike.

“Papilio Buddha” was censored and initially denied release in India, a fact that underscores the discomfort it causes to dominant caste structures. As a cinematic text, it represents an important rupture in Indian film history, insisting that Ambedkarite cinema must not only depict resistance but embody it. In a nation where Dalit stories are often muted or mediated, “Papilio Buddha” speaks in a voice that is loud, proud, and deliberately dissonant.

14. Manthan (1976)

Shyam Benegal’s “Manthan” (“The Churning”) stands as a significant intervention in Indian parallel cinema, blending realism with a vision of rural transformation. While the film ostensibly centers on the White Revolution and the rise of dairy cooperatives in Gujarat, its deeper subtext explores the deeply entrenched hierarchies of caste and class that structure rural Indian life.

Scripted by the celebrated playwright, Vijay Tendulkar, and funded collectively by five lakh farmers of Amul, “Manthan” is rooted in the ideals of cooperative self-reliance. Yet it refuses to romanticize the rural. It lays bare the fault lines that separate upper-caste landowners from lower-caste labourers, drawing attention to how socio-economic reforms are often subverted by caste-based power.

The protagonist, Dr. Rao (inspired by Verghese Kurien), represents the modern, developmentalist state seeking to usher in egalitarian reform. However, his technocratic optimism collides with the lived realities of caste oppression. The character of Bhola (Naseeruddin Shah), a Dalit dairy worker, becomes central to this collision. His exclusion from decision-making and his vulnerability to both exploitation and violence reflect the structural limitations of reform that do not actively dismantle the caste.

From an Ambedkarite perspective, “Manthan” is notable not for radical assertion but for demonstrating the limits of reformist models that fail to address caste as the axis of social power. The film asks whether economic empowerment alone can transform deeply hierarchical social relations, or whether genuine change demands a more confrontational reordering of power, as envisioned by Ambedkar. Importantly, it introduces powerful Dalit characters as parallel heroes and agents of change, distinct from the stereotypes attached to the conventional Dalit identity.

13. Paar (1984)

Goutam Ghose’s “Paar” is not merely a film, it is an ordeal, a lament, a desperate howl against the centuries-old institution of caste. Based on a Bengali story by Samaresh Basu, it is one of the most harrowing cinematic representations that intersect caste, class, and systemic exploitation in postcolonial India. Set against the brutal backdrop of rural Bihar, the film follows Naurangia (played with haunting intensity by Naseeruddin Shah) and his wife Rama (Shabana Azmi), a Dalit couple forced to flee their village after a violent reprisal by upper-caste landlords.

Their crime? Demanding wages, asserting dignity, and daring to live. At its core, “Paar” dramatizes Ambedkar’s critique of caste as a social and economic structure designed to dehumanize. The couple’s forced migration mirrors the experiences of countless lower-caste and landless labourers who are uprooted not just physically but symbolically, from their rights, dignity, and citizenship. Their passage from village to city and, finally, to an act of extreme endurance, swimming across a river with a herd of pigs, becomes a metaphor for the moral and physical toll of caste oppression.

Unlike many narratives that sentimentalize poverty, “Paar” foregrounds systemic violence and powerlessness. It critiques both feudal and modern forms of caste-based exploitation while offering an embodied view of suffering. The film’s realist aesthetic, documentary-like cinematography, minimal music, and raw performances, amplify its political urgency. It reveals how caste is stitched into the soil, baked into hunger, and coded into migration.

Rama’s resilience and Naurangia’s despair stand in for millions whose lives are shaped by inherited indignity and institutional violence. It is a film about movement – geographical, political, existential – and about what it means to carry your caste on your skin, across borders, rivers, and time. More than four decades later, “Paar” remains a blistering reminder that justice in India often demands an unbearable price. It does what great cinema must: witness suffering, question silence, and compel us to ask, how far must the oppressed swim before reaching the shore?

12. Witness (2022)

Deepak’s “Witness” is one of the most powerful contemporary Tamil films to foreground the violence of caste through the lens of sanitation labour, a sector deeply entangled with caste-based occupation and the logic of purity and pollution. The film centres on the death of a young Dalit man inside a septic tank, a tragedy that remains shockingly common in India and is emblematic of the caste system’s dehumanizing division of labour.

This isn’t just about poverty or negligence; it’s about how caste assigns value to lives. The film’s strength lies in its refusal to treat this death as an accident; it is positioned as institutional murder, enabled by the silent complicity of caste, bureaucracy, and urban modernity. The film explores how caste persists in the seemingly progressive, metropolitan spaces of the Indian city. It reveals how even in the face of Dalit migration to cities, caste follows through occupation, architecture, and silence.

The story is told through the perspective of a mother (played brilliantly by Rohini) who moves from mourning to political awakening, fighting for justice and recognition. The film interrogates how caste operates through invisibility and how those oppressed by it must reclaim the right to name their oppression. In doing so, it enacts a cinematic Ambedkarite intervention: it refuses erasure, demands dignity, and insists on justice.

With minimal melodrama and a keen sociological eye, “Witness” emerges as a vital text in anti-caste cinema. In its portrayal of manual scavenging and the state’s failure to eliminate it despite constitutional safeguards and legislation, “Witness” echoes Ambedkar’s critique of structural caste, not just as a rural or religious problem, but as a modern, institutional one.

11. Chomana Dudi (1975)

In the heart of Karnataka’s soil, where caste is older than memory and deeper than roots, “Chomana Dudi” (“Choma’s Drum”) beats like a wound that refuses to heal. A seminal Kannada film that poignantly explores the emotional and existential landscape of caste oppression in rural India, it is known for its unflinching portrayal of untouchability, landlessness, and the spiritual violence inflicted by the caste system. B.V. Karanth’s haunting adaptation of Shivaram Karanth’s novel tells the story of Choma, a Dalit bonded labourer, who dreams of tilling a piece of land, a desire forbidden to him by the structures of caste.

He is beaten down not by one oppressor but by an entire system, wrapped in the rituals of caste purity and economic bondage. Choma’s son dies on a plantation, his daughters are exploited, and he is left alone to dudi (drum) out his despair into the indifferent air. His passion for the soil, his frustration, and his struggle for dignity are echoed in the rhythm of his drum, which becomes a metaphor for both his isolation and his unarticulated resistance. Choma’s longing to claim agency over land and life speaks to Ambedkar’s assertion that land reform and economic self-reliance are essential components of Dalit emancipation.

The film does not frame Choma as a victim in the simplistic sense; rather, it shows the psychological weight of oppression, the deep desire for selfhood, and the impossible constraints imposed by caste Hinduism. In denying him land and autonomy, the system denies his humanity. His final act, dancing and drumming in furious solitude, becomes a symbolic rebellion, a solitary but resonant echo of Ambedkarite critique.

“Chomana Dudi” predates the rise of overtly Ambedkarite cinema, but its thematic focus aligns deeply with Ambedkar’s vision: the need to annihilate caste not only through law but by exposing the deep-seated cultural codes that sustain it. As a work of anti-caste cinema, it remains a powerful document of rural marginality, social exclusion, and the quiet, rhythmic beat of resistance.

10. Sairat (2016)

“Sairat,” yet another anti-caste film from Nagraj Manjule, is a landmark in Marathi and Indian cinema for its bold and unapologetic interrogation of caste within the framework of a romantic tragedy. While it adopts the surface conventions of a youthful love story, replete with music, elopement, and rebellion, it ultimately subverts the genre, exposing the violent undercurrents of caste power that shape social reality in India.

The film follows the story of Parshya (Aakash Thosar), a lower-caste boy, and Archi (Rinku Rajguru), an upper-caste girl, whose romance defies the rigid norms of rural Maharashtra. Their love is tender and sincere, but it is also perilously transgressive. In portraying the couple’s escape from their village and the subsequent attempt to build a life outside caste restrictions, “Sairat” foregrounds the illusory nature of freedom in a society where caste violence is both systemic and intimate.

Manjule, himself from a Dalit background, uses his directorial voice to shift the gaze from the dominant-caste centre to the margins, thereby recasting the genre as a site of resistance. The cinematic space is infused with Ambedkarite politics, not through didactic dialogue, but through its structural critique of caste privilege and the brutal costs of its defiance. The film’s shocking ending, which refuses the comfort of narrative closure, is a political act in itself: a refusal to romanticize caste-blindness and a reminder of the real consequences of inter-caste transgression.

“Sairat” thus emerges not merely as a tragic love story but as a social document that challenges the myth of caste neutrality in modern India. Its popularity underscores the power of cinema to spark critical conversations on caste, love, and violence, making it an essential work within the canon of anti-caste and Ambedkarite cultural expression. “Sairat” is a powerful reminder that in India’s caste-ridden and patriarchal society, caste pride often outweighs human life itself, proving that caste can, and often does, triumph over love.

Related to Movies about Caste Discrimination: Sairat (2016): Exploration of Inter-sectional Identity in Indian Cinema

9. Asuran (2019)

In “Asuran,” the earth is soaked in blood, not just from revenge but from history. Based on the novel “Vekkai” by Poomani, Vetrimaaran’s visceral drama is more than a tale of personal loss, it is a blistering portrait of caste oppression, land politics, and the simmering rage passed from one generation to the next. The soil of rural Tamil Nadu becomes a battleground, where owning even a handful of land is seen as a dangerous form of Dalit assertion. “Asuran” thus becomes a significant film in the landscape of contemporary anti-caste cinema.

Sivasaami (played with quiet ferocity by Dhanush) is a man scarred by the memory of what caste can do to a man who dares to rise. The narrative unfolds around Sivasaami’s Dalit farming family, whose modest rise through land ownership is perceived as a transgression by dominant caste landlords. This perceived breach leads to brutal retribution, triggering a cycle of violence and resistance. The film balances a tension between two modes of Dalit response: the father’s cautious survivalism, shaped by his traumatic past, and the son’s raw thirst for justice.

“Asuran” is not merely about physical survival, it is about the assertion of dignity in the face of structural dehumanization. It embodies Ambedkarite principles, particularly the insistence on land rights as foundational to social justice and the exposure of caste not as an outdated relic but as a continuing material and ideological force. Vetrimaaran’s direction resists melodrama, instead focusing on the psychological and social costs of oppression and rebellion. The film also subverts typical hero narratives by centering Dalit subjectivity without romanticisation.

Sivasami’s backstory – where education, love, and dignity are all crushed under the weight of caste – evokes Ambedkar’s own call for the annihilation of caste as a prerequisite for true democracy. The film’s layered structure and nonlinear storytelling reflect the complexity of resistance itself: it is not always triumphant, but it endures.

In “Asuran,” every ember tells us that to claim dignity is a dangerous act. But claim it, they do. And in that act, the oppressed become the authors of their own legends. Sivasaamy’s final, illuminating words to his son echo the core of Ambedkarite philosophy: “If we own land, they’ll seize it. If we carry wealth, they’ll steal it. But if we possess education, no one can ever take it from us.”

8. Puzhu (2022)

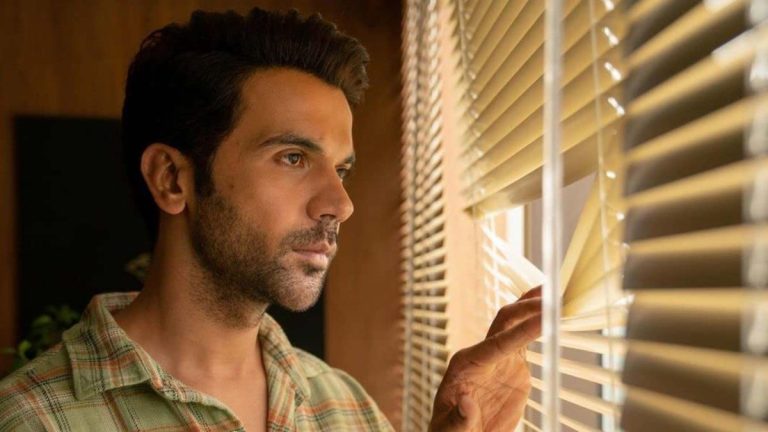

“Puzhu” (“Worm”) slithers in silence. It poisons slowly, revealing how caste does its most insidious work not through spectacle but through the quiet cruelty of everyday control. In her debut feature, Ratheena P. T. crafts a slow-burn psychological drama that doubles as a chilling study of upper-caste anxiety and savarna fragility, masked as a moral order. The most impactful aspect of this film is that it casts superstar Mammooty in a deeply uncharacteristic role, that of a villainous, mentally unstable bigot. This film marks a rare moment in Indian cinema where caste is explored not from the margins but from within the psyche of the oppressor.

Mammootty, shedding the glamour of his star persona, delivers a haunting performance as Kuttan, a retired intelligence officer, a single father, and a man obsessed with discipline and ‘purity.’ But beneath his calculated routines lies a deep rot: the fear of contamination, the paranoia of losing control, the rage of a caste mind challenged by love that crosses lines he deems sacred.

When his sister falls in love with a Dalit man, Kuttan does not explode, he tightens his grip. The violence in “Puzhu” is emotional, suffocating, and internalised. It’s not the brutality of batons but of whispers, doubts, and manipulations. Caste here is not a system, it is a disease of the mind, festering in silence.

The ideological tension emerges most clearly in Kuttan’s increasing discomfort with his sister’s romantic relationship with a Dalit theatre artist. His casteism is not expressed in slurs or spectacle but through surveillance, manipulation, and emotional domination, suggesting how caste operates from the private, familial, and psychological spheres. This approach reflects Ambedkar’s insight that caste is not merely a system of social hierarchy but a mode of consciousness sustained through fear, purity, and control. What distinguishes “Puzhu” within the canon of caste cinema is its refusal to sensationalize.

It interrogates the internal corrosion caused by caste ideology and invites viewers to witness the unravelling of an upper-caste man’s moral world. The film’s title, meaning “worm”, is not incidental. Kuttan becomes the very thing he fears: consumed from within, crawling through the wreckage of his own decaying power. In a landscape where caste often appears as an external conflict, “Puzhu” dares to look inward, exposing the psychological inheritance of savarna dominance. It is an indictment of savarna self-righteousness, and in its discomforting gaze, it aligns with the Ambedkarite project of truth-telling and structural critique.

Related to Movies about Caste Discrimination – Puzhu [2022] ‘SonyLIV’ Review: A brooding deconstruction of privilege

7. Kaala (2018)

How often does an oppressed subject, the Other, get to see, view, and claim himself on the screen? The profundity of Dalit cinema is to be real and critical in the celebration of the Dalit self. Pa. Ranjith’s “Kaala” (“Black”) stands as a bold assertion of Dalit identity rooted in Ambedkarite consciousness and proudly grounded in the radical maxims of Budhha-Phule.

It is a politically charged film that reimagines the gangster genre as a canvas for articulating Ambedkarite resistance. Set in the slums of Dharavi, Mumbai, an urban microcosm of marginalised India, the film confronts the intertwined structures of caste, class, and power through its central protagonist, Karikaalan, known as Kaala, played by Rajinikanth.

Kaala, a Tamil Dalit leader of the slum, becomes the symbolic and literal face of resistance against Brahminical and corporate hegemony. He faces off against Hari Dada (Nana Patekar), a real estate baron and political manipulator whose dream of a “clean” city is code for erasing the poor, the Dalit, the dark-skinned. Hari Dada is an embodiment of caste power cloaked in the rhetoric of development and cleanliness, metaphors often mobilised to invisibilise and displace the working poor, especially Dalits. Kaala, in contrast, asserts the right of the oppressed not just to survive but to live with pride, colour, and dignity.

“Kaala” is deeply embedded in Ambedkarite thought, not only through its overt references to land rights and social justice but also in its structural reconfiguration of power. The film refuses savarna heroism, instead centering on a subaltern hero who leads collectively, resists non-violently, and upholds the sanctity of constitutional values. It emphasizes the land as a site of autonomy and conflict, aligning with Ambedkar’s understanding of socio-economic emancipation as foundational to any true equality.

The film’s visual language, marked by dark tones, vibrant murals, and the symbolic prominence of the colour black, serves as a powerful aesthetic declaration of Dalit assertion and cultural identity. Ranjith’s direction transforms the mass entertainer into a vehicle of radical pedagogy. “Kaala” is not merely a film about the poor fighting the powerful, it is a cinematic manifesto that reclaims space, culture, and political agency for the oppressed, echoing Ambedkar’s call to “educate, agitate, organise.”

6. Article 15 (2019)

Anubhav Sinha’s “Article 15” represents a significant intervention in contemporary Hindi cinema by directly addressing the persistence of caste-based violence and discrimination in postcolonial India. The film derives its title from Article 15 of the Indian Constitution, which prohibits discrimination on the grounds of religion, race, caste, sex, or place of birth. By invoking this constitutional provision, the film foregrounds the gap between legal idealism and lived realities for Dalit and marginalized communities.

Set in rural Uttar Pradesh and inspired by real-life events such as the 2014 Badaun rape case, “Article 15” follows Ayan Ranjan, an upper-caste, urban police officer newly posted in rural Uttar Pradesh, where the discovery of two Dalit girls hanging from a tree sets off a chain of revelations. Through Ayan’s increasing awareness of the systemic violence around him, the film exposes how state institutions, particularly the police, are complicit in perpetuating caste-based oppression. He is forced to confront a landscape where caste is not just a relic of the past, it is the architecture of the present. It decides who cleans drains, who fetches water, who lives, and who dies.

While the protagonist’s position as a savarna outsider has drawn critical scrutiny, the narrative still manages to center Dalit suffering and resistance through the testimonies and absences of the oppressed. Thematically, the film aligns with Ambedkarite thought by emphasizing that caste is not merely a rural or cultural problem but a structural issue that undermines the very foundations of democracy and justice. It critiques the state’s failure to protect its most vulnerable citizens and implicitly calls for a radical reimagining of social relations, echoing B. R. Ambedkar’s vision of equality, dignity, and fraternity.

Although “Article 15” stops short of offering a fully decolonial or Dalit-centered cinematic language, its commitment to foregrounding caste in a commercial format marks an important step in mainstreaming Ambedkarite concerns within Indian popular culture. It is an indictment of a society where the Constitution’s promises remain systematically denied to those at the bottom of its hierarchy. The film, grim and gritty as it is, asks us whether that promise has ever been kept. It doesn’t offer a resolution. It offers confrontation. Sometimes, that is where change begins.

5. Jai Bhim (2021)

“Jai Bhim” opens not with a crime but with a ritual humiliation, the dehumanizing routine of prison authorities segregating “habitual offenders,” all from oppressed castes, stripping them bare of not just clothes but dignity. From that moment, the film makes its mission clear: to expose the systemic rot of caste violence embedded deep within India’s institutions.

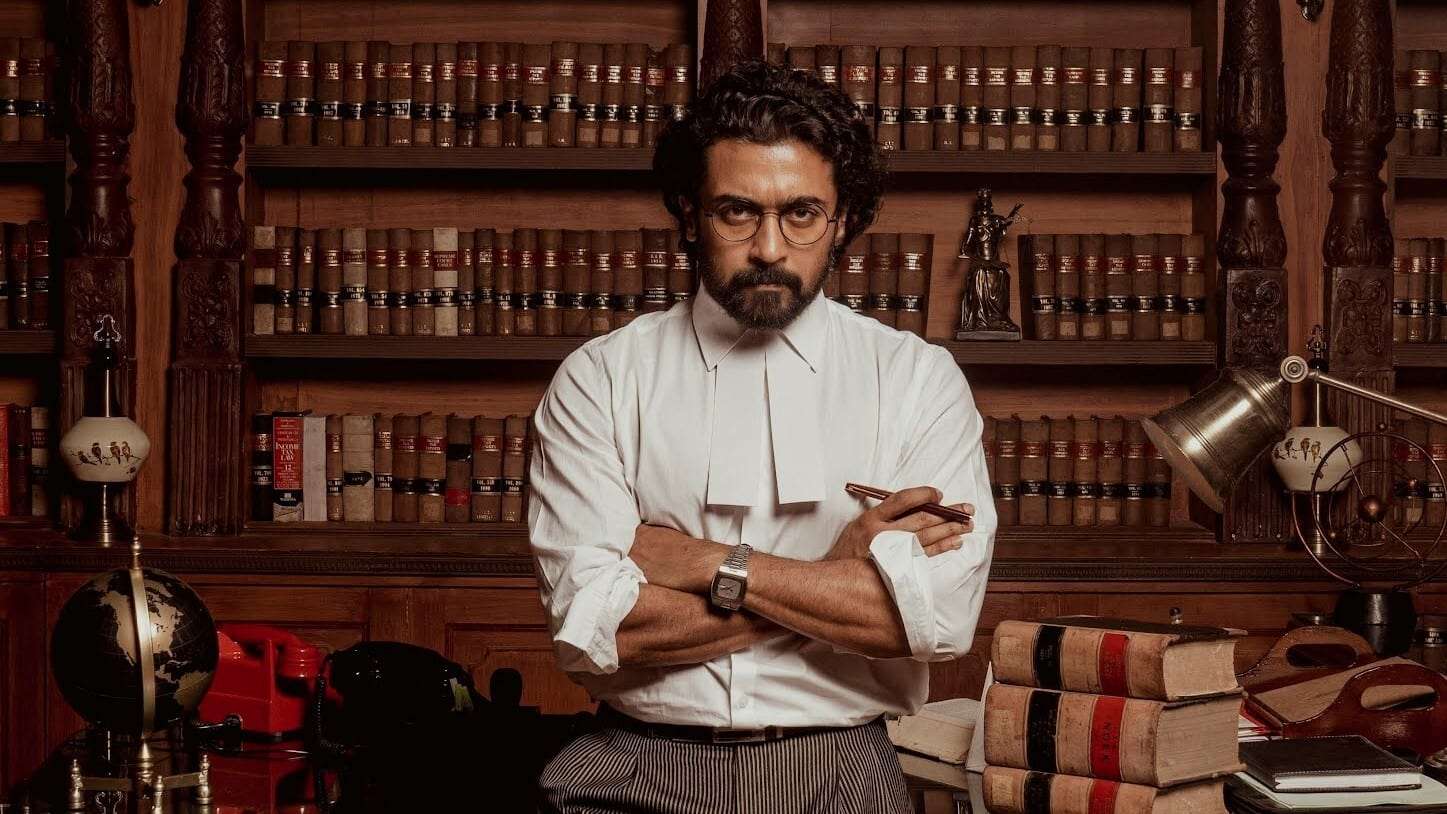

T. J. Gnanavel’s critically acclaimed “Jai Bhim” is a landmark Tamil film that offers a trenchant critique of caste-based state violence while foregrounding legal resistance rooted in Ambedkarite principles. Based on a true incident from 1993, “Jai Bhim” follows Chandru (Suriya), a lawyer inspired by Justice K. Chandru, who takes up the case of Sengeni (Lijomol Jose), a pregnant Irular woman whose husband Rajakannu (Manikandan) disappears after police detention. It is not just a legal drama but a piercing indictment of a caste-ridden state machinery that criminalizes the very existence of the marginalized.

From the outset, the Irular community is depicted as structurally disenfranchised, routinely subjected to surveillance, arbitrary detention, and physical torture by police authorities. Through the investigative and courtroom sequences, “Jai Bhim” illustrates the gap between constitutional ideals and the realities of caste oppression in contemporary India. At the centre of this narrative is the law, not as a neutral mechanism but as a site of struggle. The film resonates strongly with B. R. Ambedkar’s belief in the power of legal and constitutional tools to challenge caste hierarchies.

Chandru’s character, played by Suriya, represents a vision of progressive jurisprudence, wherein advocacy for the oppressed is both a moral imperative and a political act. But the heart of the film beats in Sengeni’s struggle, her tears, her resolve, her refusal to be silenced. “Jai Bhim” is not content with showing individual acts of cruelty; it zooms out to show a system built to protect the powerful and crush the powerless.

The film is both a tribute to Ambedkarite thought and a battle cry. It affirms that the law, when wielded with moral courage, can be a tool of liberation. The courtroom becomes a site of confrontation, not just of facts, but of histories. “Jai Bhim” is not a slogan here. It is a lifeline, a legacy, and a promise.

4. Ankur (1974)

Before caste became a whispered presence in mainstream Indian cinema, Shyam Benegal’s “Ankur” spoke it aloud, in grainy frames, in silences that seethed, and in characters denied the luxury of choice. Cited as a significant film in India’s Parallel Cinema movement, particularly for its direct and critical exploration of caste issues, it brought about a new cinematic vocabulary for injustice. The film starkly portrays the power dynamics between upper-caste landowners and lower-caste labourers within rural feudal structures, showcasing how caste intersects with class and gender to perpetuate exploitation and oppression.

Set in rural Andhra Pradesh, “Ankur” tells the story of Lakshmi, a Dalit woman played with extraordinary sensitivity by Shabana Azmi in her debut role. Her husband, Kishtayya (Sadhu Meher), a deaf labourer, is driven to the city in search of work, leaving Lakshmi behind to toil under the gaze of Surya (Anant Nag), the landlord’s son – young, entitled and freshly returned from the city with modern education and feudal arrogance intact. Surya’s seduction of Lakshmi is less romantic than it is a reflection of entrenched power, wrapped in liberal guilt and caste entitlement. Her resilience, her quiet resistance, becomes the heartbeat of the film.

“Ankur” doesn’t shout. It murmurs truths that wound deeper. It strips caste of all abstraction and roots it in the domestic, the intimate, and the unbearably real. Moreover, it does not offer a revolution, but it points to the simmer. Though made decades before the word “Ambedkarite” found cinematic circulation, “Ankur” is in dialogue with his ideas. It exposes the moral decay of privilege, the double standards of upper-caste progressivism, and the cost of dignity when it is systemically denied.

In its final moments, a child throws a stone through the window – a jolt, a question, a call. It echoes across the decades. The system may be old, but the resistance is always young. As an early cinematic critique of caste from a feminist lens, “Ankur” remains essential viewing for any serious engagement with the politics of representation in Indian cinema.

Also Read: The 10 Best Shyam Benegal Movies

3. Pariyerum Perumal (2018)

Some films don’t just tell a story, they name a wound. “Pariyerum Perumal” is one such film. Mari Selvaraj’s stunning debut is an unflinching, quietly devastating portrayal of caste oppression in contemporary Tamil Nadu. It follows Pariyan (Kathir), a young Dalit man with dreams of becoming a lawyer, as he enrolls in law school, only to find that the real courtroom is society itself, and the verdict is always rigged.

At first, Pariyan is full of innocence and ambition. His friendship with Jothi Mahalakshmi (Anandhi), an upper-caste classmate, sparks warmth but quickly invites surveillance, suspicion, and violence. Every interaction becomes a site of caste power, polite smiles hide deep-rooted prejudice, and kindness can quickly turn into cruelty when social boundaries are crossed.

What makes “Pariyerum Perumal” extraordinary is its poetic restraint. There is no melodrama, only mounting dread. The violence is not sensational but systemic—embedded in glances, gestures, and the institutions that fail Pariyan at every turn. Through its pacing, visual metaphors, and Yogi Babu’s unexpectedly tender presence, the film carves out a deeply human narrative about survival and dignity. The haunting figure of a local caste killer, who stalks like a spectre throughout the film, reminds us that for many, the price of assertion is death.

Yet “Pariyerum Perumal” is not a film of despair. It is a film of defiance. Its Ambedkarite core is clear: educate, agitate, organize, but above all, endure. The final moments, where Pariyan speaks directly and with clarity, are among the most powerful declarations of self-respect in Indian cinema. In his calm is fire. In his composure, a quiet revolution. “Pariyerum Perumal” does not scream. It resists. And that resistance echoes.

2. Fandry (2013)

In a village where caste is written into the soil and spoken in every silence, “Fandry” erupts like a scream long held in the throat of history. “Fandry,” meaning “pig” in Marathi, is a searing portrayal of caste and humiliation set in rural Maharashtra. Nagraj Manjule’s directorial debut unfolds through the eyes of 13-year-old Jabya (Somnath Awghade), a Dalit boy who dares to dream of love, escape, and dignity. The film captures both the tenderness of adolescence and the brutality of a social order that punishes hope.

Jabya belongs to a family tasked with catching pigs, a job that marks them visibly and invisibly. As he falls for an upper-caste classmate, Shalu (Rajeshwari Kharat), he dreams of escaping his oppressive circumstances, but unfortunately, his world brims with longing and humiliation. The schoolboys’ laughter, the villagers’ offhand cruelty, the dehumanizing rituals of daily life, these accumulate, not as background noise, but as the very architecture of oppression. What begins as a tender coming-of-age story quickly unravels into a powerful indictment of caste-based discrimination and the illusion of social mobility.

Manjule crafts a film that is as lyrical as it is political. He captures the quiet violence of caste through everyday interactions, glances, silences, and the casual cruelty of those who never question their privilege. The film’s realism is unsettling, especially in its depiction of how desire, dignity, and belonging are denied to those at the bottom of the caste hierarchy.

“Fandry” builds slowly but ends with an unforgettable gut punch: an explosive act of rage and defiance that breaks the silence Jabya has been forced to endure. The film does not offer resolution or redemption; instead, it leaves us with discomfort, and the urgent need to reflect. A landmark in anti-caste cinema, “Fandry” is not just a film about a boy, it’s a film about a system that crushes boys like him every day. Pigs may never fly, but revolution begins in rage. And in “Fandry,” rage finds its voice.

Related to Movies about Caste Discrimination: The 15 Best Marathi Movies of the 21st Century

1. Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar (2000)

What better film to lead this list than one that tells the story of Dr. Ambedkar himself, a life that embodies the very essence of his ideology, a life that did not merely resist caste but reimagined India from its margins? “Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar,” directed by Jabbar Patel and headlined by Mammootty in a National Award-winning performance, is more than a biopic, it’s a cinematic testament to one of the most radical thinkers and humanists of the modern world.

Spanning from Ambedkar’s early struggles as a Dalit student in an unforgiving caste society to his education abroad, political battles, and ultimately, his pivotal role in drafting the Indian Constitution, the film humanizes a towering figure while underscoring the radical nature of his politics. But it’s not just his rise the film captures, it’s his resistance: to Brahmanism, to tokenism, to the slow violence of silence.

The film does not shy away from the ideological confrontations Ambedkar had with dominant caste leaders, including Gandhi, or from the intense personal costs of his lifelong battle against caste. It highlights his advocacy for labour rights, gender equality, and social justice and concludes with his historic conversion to Buddhism, a deeply political and spiritual act of defiance against caste Hinduism and a call for liberation that continues to resonate.

It serves as a vital educational and political tool, offering an in-depth look at the life of a man who redefined justice for the downtrodden and oppressed classes in India. Mammootty’s portrayal is the film’s beating heart. Mammootty doesn’t mimic Ambedkar, he inhabits Ambedkar with rare gravitas. His Ambedkar is not a saint carved in stone but a man of flesh, fury, intellect, and immense sorrow. The film’s emotional power lies in its silences as much as in its speeches. It remains one of the most significant cinematic tributes to Ambedkarite thought and continues to inspire generations seeking dignity and equality.

Among the film’s most unforgettable moments is the Maharaja of Baroda’s prophetic declaration: “You have found your saviour in Ambedkar, and I am confident he will break your shackles.” These words, spoken to the marginalized sections of India, echo through history and into the present, an affirmation of Ambedkar’s unwavering fight for liberation. In capturing his life, this film doesn’t just recount history, it reignites a movement. Jai Bhim!