Ritwik Ghatak was born in Dhaka in 1925 and spent his boyhood in East Bengal (Bangladesh). He witnessed the Bengal Famine, World War II, and finally, the Partition. He became actively associated with the Indian People’s Theatre Association. He was highly influenced by Brecht, Stanislavski, Eisenstein, Godard, and Buñuel.

Finding and formulating his own opinion during those brewing years of a post-war Bengal troubled by communal riots and partition, he developed embryonic signs of a greater realization that germinated in his films, which, thanks to his acumen of observation and apt realization of using sound as a carrier of the narratives made his films pages out of people’s lives who were just as real and in a state of psychosis.

Deep insight into human reflexes and typical reactions of human virtues worked in a very curious way. Where history fails to account for an explanation, Ritwik Ghatak interrogates the relevance of an existential situation that forces lives to alter beyond all limits and boundaries, concluding in the formation of ‘rows and rows of fences.’

His strange passion for rivers, Padma, Ganga, Subarnarekha, and Titash, is a metaphorical reflection of his own life, which, like a river, flows on, beyond arguments and stories. Beyond Death.

Related to Ritwik Ghatak: Essential Bengali Films of the 2010s Decade

Ghatak scripted 17 feature films, of which nine were released, and eight were abandoned. He did minor roles in six feature films, including three of his own – Subarnarekha, Titash Ekti Nadir Naam, and Jukti Takko Aar Gappo. His first film was Bedeni. He had to abandon this due to a camera flaw. The number of projects Ritwik had to give up could make a book. Few know about his abandoned documentary on Indira Gandhi in 1972. Few know of his ad film for Imperial Tobacco to fetch money to complete Subarnarekha.

Other memorable films he had to abandon are Kato Ajanarey (1959), and Bagalaar Bangadarshan stopped after a week’s shooting in 1964-65. The most creative period in Ritwik’s career was between 1952 and 1967. It began with Nagarik, followed by Ajantrik, Bari Thekey Paliye, Meghe Dhaka Tara, Komal Gandhar, and Subarnarekha. This was punctuated with a spurt of documentaries. Memorable among these are Orson (1955), Ustad Allauddin Khan (1963), Fear (1964-65), and Scientists of Tomorrow (1967).

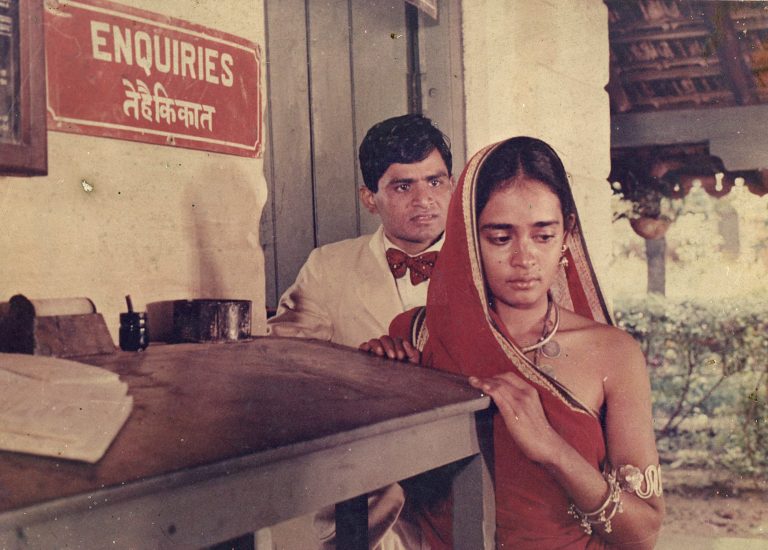

8. Jukti, Takko Aar Gappo (Reason, Debate and A Story) (1974)

Jukti, Takko Aar Gappo is “about a failed life and an argument that goes beyond it, beyond Ghatak himself,” according to Geeta Kapur in her study of this film titled Self into History: Ritwik Ghatak’s Jukti Takko Aar Gappo. “When he made Jukti in 1974, he was at the end of his tether; his health and sanity were disintegrating. But he was astute enough to realize that the nation, polarized among political expediency and ultra-radicalism, was on the brink, and if it were the last thing he did, he would intervene as an artist.”

Jukti, Takko Aar Gappo was Ghatak’s violent assertion of unity for human dignity. He sang through it, as through his other films, like a great poet. “No filmmaker can change the people. The people are too great. They are changing themselves. I am only recording the changes that are taking place,” Ghatak once said in his quintessentially unique brand of English.

7. Titas Ekti Nadir Naam (A River Called Titas) (1973)

Titas Ekti Nadir Naam (1973) revealed Ghatak’s obsession with the female principle all over again. The film revolves around the life and ultimate dissolution of a fishing community on the banks of the river Titash in Bangladesh. Around the film’s time setting, forty years before it was made, the river starts drying up. Death and starvation threaten the lives of the fishing community. Urban vested interests enter to exploit the situation. The fishermen are displaced, and Basanti alone stays back, a live witness to and victim of the decadent, tragic reality.

Related to Ritwik Ghatak: Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne (1969) Analysis

Ghatak draws a visual metaphor of the drying up of Titash with the drying up of Basanti, who dies as the river does. She drags herself to the sandbanks and claws into the soft earth for water so that she can perform her death rituals herself. During those last dying moments, she watches a child run through the lush green paddy fields, playing on a leaf whistle against the stark silence of Basanti’s death.

Ghatak’s ambivalent perception and critique of motherhood metamorphoses into a thought-provoking treatment. Basanti, Mungli, Malo, and the other women in Titash Ekti Nadir Naam are fiery creatures, unlike the simpering, passive, and helpless women of the average Indian film. They tower over the male characters in their humanism, their defiance of corruptive forces that arrive to uproot them, and their decisive and collective solidarity that brooks no rupture.

When Basanti entices a landlord’s agent into a hut, a group of women bashes him up for having made advances to Basanti. When the young, widowed mother of Ananta, the little boy, arrives at the village for refuge, unknown and anonymous among the villagers, the men look at her with suspicion. But the women rally around her and offer her support.

6. Bari Theke Paliye (1958)

Bari Theke Paliye is an enjoyable film that critics say contains autobiographical accounts from Ghatak’s own truant childhood. It is the story of a young boy who runs away from his village home to a large city.

Though the city remains unnamed, we see Calcutta on screen. Kanchan, the little boy, gets help in the city from people on the fringes of society, simple people who go unnoticed. One is a teacher who has turned to peddling on the streets – a subtle jibe at what Calcutta does to a person’s right to live with dignity. Another benefactor is an aging domestic maid. A third is a gangster disguised as a magician, a cart puller, and a rich girl.

In the end, the boy comes home, having summed up that “the city is an aberration.” Ghatak’s focus is on the goodness of small people, which gets swallowed up by the ‘aberration’ of the machine-driven environment of the city. Obviously, he is referring to Calcutta though this time, he refrains from naming it.

Ritwik Ghatak indulged in some technical experiments in this film. For instance, the speed of a particular sound was increased on the transferring table, or the use of special lens (300) brought forth fascinating results when the wheel of a car appeared to rotate even while the car was static. The use of an 18-mm lens captured objects in their distortion.

5. Nagarik (1977)

Ghatak claimed that Nagarik was a political statement. It set out to analyze the agonies of a middle-class family in Calcutta engaged in a grim struggle for survival against oppressive social forces. It portrayed the slow and tragic descent of a middle-class family. This descent, several rungs down the hierarchical ladder of the socio-economic class structure, was geographic on the surface – the family moved home from one pocket of the city to a seamier and lower pocket.

But beneath this surface lay the decay in the lives of each member of the family. Their characters had metamorphosed into something quite different from what they were when the film opened. In many ways, Nagarik reflects some of the misgivings Ghatak felt when he first landed in Calcutta. Ghatak did not bother to cloak his visuals with verbal niceties. This brutal insight into the nature of a city and its people appears amazing even across bridges of time and space.

With one whip-leashing stroke of his directorial wand, Ghatak slashed open the stomach of this vibrating, sick city, revealing its ugly innards, right in front of the eyes of the viewer till they wished to look away. Ghatak portrays Calcutta as a victimizer of its people. At the same time, he also shows the city as the helpless victim (a) of refugees pouring in by the thousands, (b) of the galloping poverty, and (c) of squalor, which turned the city into a huge drain flowing with human blood, human waste, and human desperation.

Related to Ritwik Ghatak: How Ray’s Pratidwandi Explores The Rapidly Changing Facade of Calcutta

Ghatak’s personal pain comes alive on screen with palpable effects. One identifies with the pain he felt as he watched people sliding down the socio-economic ladder, the pain of seeing Ramu, the teacher’s son, forced into accepting the job of a wage laborer for want of a better job as his sole means of survival. Ramu moves into a slum with his widowed mother. Ramu drifts away from his girlfriend, Uma.

One watches and feels the pain with which Ghatak portrays Uma’s sister giving herself up to prostitution. We watch, with an equal feeling of helplessness, the pain of a talented singer compelled to sing cheap commercial songs. The film closes with strains of the ‘Communist Internationale’ filling the soundtrack.

Was this Ritwik’s way of suggesting a Marxist solution to this gross inequality between man and man, family and family? Not really. He offers Ramu’s own family as a point of comparison against itself. The change in the family at the end is so drastic that it almost defies recognition with its own image at the beginning of the film.

4. Ajantrik (Pathetic Fallacy) (1958)

This was based on a short story, Ajantrik, by Subodh Ghosh (known internationally as The Unmechanical, The Mechanical Man, or The Pathetic Fallacy). It is one of the earliest Indian films to portray an inanimate object, in this case, an automobile, as a character in the story. It achieves this by using sounds recorded during post-production to emphasize the car’s bodily functions and movements. It was one of the few films to win critical acclaim abroad.

Ajantrik rejects all associations of machines with monstrosity and, therefore, is unable to emotionally communicate with a human being. The film tellingly brings out the relationship between the animate and the inanimate, exemplifying the unification of the ‘conflict of images’ and the pathos that goes with it. The film humanizes Jagaddal, a Chevrolet reduced to a jalopy, thus christened by its master, yet draws attention to the fallacy of investing an inanimate or natural object with human feelings.

An innovation in Nagarik that became a characteristic of his later style was the use of deep focus to place his characters firmly in their social environment. The first visual introduction of the central character in the film comes only after a panoramic sweep of Calcutta, the camera panning over shanties and shops, high-rise buildings and ghettoes, electric wires cob webbing the skyline and streets crowded with common people going about their daily chores.

This is followed by a long crane shot from a height of about 20 feet that introduces the character, one of the crowd, helping an old woman to cross the street. He tracks the man to his house through narrow and dirty by lanes, passing street performers and beggars. The camera then closes up on the face of the hero. By then, the audience has accepted Ramu as a point of identification, as one of them, in no way extraordinary, heroic, rich, handsome, or promising of adventures in a fantasy world.

3. Komal Gandhar (E-Flat) (1961)

Komal Gandhar is an autobiographical film and the resolution in terms of personal hope and compassion through surviving social contradictions. The story revolves around a group of youngsters committed to resolving the contradictions of independent India through theatre performed in small towns and rural areas. It grew into a movement, reflecting the movement initiated by IPTA (Indian People’s Theatre Association) as the cultural wing of the CPI.

But the movement soon lost its fighting spirit and, like many others, broke up due to petty squabbles and the narrow individualistic notions within its cadre. Thematically, the film unfolds Ghatak’s constant preoccupation with the shattering of dreams he nurtured and fought for to forge a unity where all objective conditions threaten to tear up the social and political fabric that keeps people coping with new-found Independence.

Related to Ritwik Ghatak: Once Upon A Time in Calcutta: Venice Review

One scene in Komal Gandhar shows an old, confused man with unkempt hair and a dusty beard. He asks a young man about his future as a refugee. Unable to reconcile with the fact that he has to leave his fertile land near the Padma River, the man shuts his ears because everything he knows and loves is forever behind him. The director paints a ghastly yet tantalizing picture that voices the emotions of several generations of humans who were adversely affected by the political move.

2. Subarnarekha (1965)

Subarnarekha opens with the foundation of Naba Jiban Colony, a colony for refugees in Calcutta. The story zeroes in on the theme of uprooting – geographic, emotional, moral, and for Sita, even political. The storyline is deceptively simple in appearance. As the film comes across over its 132 minutes of screening time, it sends a series of electric shocks down the spine of a growingly disturbed audience. “Disturbance” aptly describes one’s reactions to Ghatak’s Subarnarekha.

The female protagonist, Sita, represents a political uprootal. Ghatak alludes to the imagery of T.S. Eliot’s The Wasteland in this film. He also uses the tunes of Patricia from Antonioni’s film La Dolce Vita on the soundtrack. Ghatak’s ‘wasteland’ is Calcutta and Sita is the ‘waste’ within it. The wasteland of Calcutta does not permit Sita the freedom to live up to the mythical name she was christened with. She cannot accept this reality when she discovers that her ‘client’ is none other than her brother Ishwar, who ‘mothered’ her. Sita’s suicide is not an escape but a violent statement of protest against the degeneration of values in a modern, disintegrated society.

Subarnarekha, according to Souroprovo Chatterjee (Structural Analysis of Ritwik Ghatak’s Cinema – With Special Reference to Ritwik Ghatak in Indian Scholar, Volume 7, Issue II, December 2020), “is an extremely powerful exploration of displacement, betrayal, social disintegration, and historical trauma, and how Ghatak endows it with the potential to resonate across cultural or temporal boundaries, are ironically, the very elements that can get lost, or at the very least obscured, in translation.

It invites us to reflect on opening up a space for revising our spectatorial habits and understanding of global art cinema and reconceptualizing the ―local‖ and the ―cosmopolitan as heterogeneous and intertwined, rather than as homogeneous and antithetical formations.”

The time setting and progress are established through historical milestones. The film opens on 28th January 1948 with a small group of refugees hoisting the national flag as a tribute to the Jallianwala Bagh massacre led by the idealist and rebel school teacher Haraprasad, a close friend of Ishwar. A few days later, we hear of the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi. Soon after Sita and Abhiram have eloped, the foreman Mukherjee brings a newspaper that carries the news of Yuri Gagarin’s first flight into space. A very angry and frustrated Ishwar tears off the pages and consigns them into the foundry fire.

The time leaps within the narrative come across through black title cards with white calligraphic writing, as if a story is being narrated through the visuals between the title cards. The credits are beautifully designed against a ‘dated scroll’ on parchment paper in beautiful calligraphic writing with the edges of the scroll torn. The music is like visual poetry expressed through songs and melodies. There is a baul number in the beginning, a pointer to bauls who are secular and live and sing beyond borders.

The cinematography is a wonderful playing around of the varied shades between the polarised black and white, with the flickering lights in the Windsor Bar when the camera focuses more on the glasses and the bottles than on the faces of the actors. The arid landscape of Ghatshila is more prominent than the flowing waters of Subarnarekha. And the racecourse fades before you realize its presence. The editing, coming from one of the greatest editors in Indian cinema, needs no comment at all because you hardly realise its presence or its functioning. Once, the camera closes on the face of Ishwar, and one can even glimpse the shimmer in his eyes behind the glasses.

The film zeroes in on the theme of uprooting – geographical, emotional, moral, and for Sita, even political. The storyline is deceptively simple in appearance. Maybe, when one reads it, it may also seem melodramatic. For example, the discovery of Abhiram’s caste from the way he identifies his dying mother at the station is pure cinematic coincidence. Ghatak defended the element of melodrama almost with a vengeance. As the film comes across over its 132 minutes of screening time, it sends a series of electric shocks down the spine of a growingly disturbed audience. “Disturbance” is a word that aptly describes one’s reactions to Ghatak’s Subarnarekha.

Yet, all is not lost. If a bit of Ishwar dies with his sister, he also begins to live again. Calcutta offers him a lifeline after having taken it away. This comes in the shape of Sita’s little son Binu, who pulls Ishwar along because his steps are now hesitant. The roles of the guardian and his ward are reversed. It is now the little Binu who guides his aging uncle Ishwar into a future of hope, if not happiness.

1. Meghe Dhaka Tara (The Cloud-Capped Star) (1960)

Three films, namely Meghe Dhaka Tara (1960), Komal Gandhar (1961), and Subarnarekha (1962), dealt with the ravaged psyche of the victims of partitioned Bengal. Together, the three are regarded as a complex, trend-setting, cinematically splendid trilogy. It is a corrosive, complex account of a refugee family with an incredibly stoic protagonist, Nita.

The three films are bonded as much by the cultural elements of Bengal – theatre, music, poetry, and song, as they are by the tragedies of the Partition that dislocated millions from their roots. Each family in the three films offers a microcosm of the refugee family, truncated into segments – emotionally and socially.

In this sense, the three films are autobiographical. The horrific spread of terror consequent to the Partition finds expression in Ghatak’s statement, “we have all become refugees of our time, having lost the roots of life.” This statement is expressed in three different ways in these three films. A press worker in Subarnarekha exclaims, “Refugee! Who is not a refugee?” Ghatak’s dream of seeing the two ‘Bengals’ united comes across movingly through the chanting of the Panchali* of Satyanarain Pooja.

Related to Ritwik Ghatak: How Satyajit Ray’s Nayak Uncovers The Facade Behind Fame

Meghe Dhaka Tara paints a brutally frank picture in stark black and white images of the family as a cannibalistic consumer of one of its own members. The ‘black and white’ does not refer to the cinematographic reality of the film. It is metaphorical and figurative in essence since the characters are painted in black and white.

History points out that cinematographically, color had not become prolific in Indian cinema when the film was made. Nita, her father, and Shankar are the ‘white’ characters. Gita, Montu, and their mother are the ‘black’ ones. Sanat is somewhere in the middle of these two extremes, weak, spineless, indecisive, and in the ultimate analysis, as cannibalistic towards Nita as the others.

Lighting, camera, and sound blend meaningfully in the scene when Shankar belts out the Tagore song, je rate more duyaarguli bhanglo jhorey (the night when the storm broke down all my doors) in his darkened room.

The lines of the song are full of hope and regeneration. The camera takes a very low-angle shot to look up at a big close-up of Nita’s face, her eyes filled with unshed tears and the sound of the whiplash intruding into the song, not once but repeatedly. The sadness of her cry, “I wanted to live!” resounding in the hills she longed to visit is visually focused on momentary disorientation in order through the circular movements of the camera followed by the broad sweeping shots, complemented with Nita’s voice distorted through the amplified sounds of her breaking-down sobs.

*Panchali is a prayer book composed in praise of the Hindu God or Goddess being worshipped at a given point of time. A priest or any member of the family chants it at the time of pooja. It narrates several stories delineating the greatness of the given God/Goddess through folk tales of kings, queens, and common people, underlining how non-believers are punished, and believers are blessed.

Summing Up

Ritwik Ghatak was born a rebel. He questioned the ideas and attitudes towards culture and art prevalent at the time. When he was forced to appear before a one-man commission, so-called progressive thinkers branded him a Trotskyite. He criticized commercial cinema, which he felt left no scope for creativity and research. Ghatak put things on screen that worried him, made him happy or sad. He was basically an aesthetic artist and was personal in his films. Films that failed to highlight Indian culture were meaningless so far as he was concerned.

Though a tragic victim of the 1947 Partition, Ritwik Ghatak brought an upbeat and celebratory insight into both the personal and national dimensions of homelessness, as reiterated constantly in his cinema. “Exile and homelessness can teach us the joy of living internally as well as externally without boundaries and without borders,” said Ghatak. The reason for the growing posthumous critical acclaim and recognition for Ghatak is, for one, the courage, power, and anger with which Ghatak dramatizes the urgent modern questions of ‘nationality,’ ‘borders’ and ‘exile.’

His first full-length feature film Nagarik, (1952), lay in damp vaults for 25 years, condemned to perpetual obscurity. A year after Ghatak died in 1976, the film was restored, and a print was taken out through the initiative of the Left Front State government.

When the film was seen in different cities of India, people began realizing the enormity of the damage done to the subsequent career of Ritwik Ghatak. Subarnarekha lay in cold storage for three years before it could be released. Ustad Allauddin Khan (1963) was released without his name as director. A short film called Amaar Lenin (My Lenin) has not been permitted public release though it was made in 1970 and given a clear censor certificate in 1971. His last film, “Jukti, Takko Aar Gappo” ran into trouble with the censors.