Ozu-esque is the word that sprang to my mind when watching Hirokazu Kore-eda’s culturally specific yet emotionally relatable nuanced family dramas for the first time. Like Mr. Yasujiro Ozu, Kore-eda goes for meticulous camera placements, prefers specific shooting style, and gracefully dilutes sentimentality out of the circumstances to deeply observe authentic human behavior. Kore-eda’s 2008 masterpiece Still Walking (aka ‘Aruitemo aruitemo‘) is considered as his most Ozu-esque work. Mr. Roger Ebert mentions the shots of trains and pillow shots in his review of Still Walking. While director Kore-eda often makes broader references to the work of Ozu, from visual as well as thematic stand point, his movies differs a lot from Ozu’s oeuvre. Inter-generational conflict, one of the key themes of Yasujiro Ozu, is also central subject in Kore-eda’s family dramas. Yet, apart from the deliberate homages to old Japanese master, Kore-eda feels like a distinct film-maker who doesn’t live in the shadows of the auteur. It would even be quite reductive to frequently refer Ozu when discussing Kore-eda’s mesmerizingly subtle character studies of flawed yet genuine human beings.

Director Kore-eda too rejects the notion of comparing his aesthetic and thematic sensibilities with Ozu. In his interview to TimeOut, the director says: “When I make films, I don’t think of any other directors or their work in terms of the rhythm of the editing or the tenor of the performances.” Furthermore, the director admits that his works are more similar in style to the cinematic master Mikio Naruse: “A more relevant Japanese master, in terms of a worldview I feel much closer to, is Mikio Naruse, whose movies really understand that humans are flawed creatures, and he makes no judgment against them”, confides Mr. Kore-eda. Mr. Dennis Lim in his essay on Kore-eda’s oeuvre (for NY Times, published under title ‘Familial Loss and Proustian Tempura’) writes, “While Ozu’s characters are paragons of calm acceptance in the face of life’s cruelties and disappointments, the characters in “Still Walking” are pricklier and less reconciled, and they have a harder time concealing their resentments.” It’s an important observation as in some of the scenes (in Still Walking) the characters openly convey their resentments and indifference, although they don’t say bad things to the people’s face. They just pass off thornier comments after that particular person has left off the room.

The inter-generational issues in Still Walking reflexively bring to mind Ozu’s true masterpiece Tokyo Story (1953). But once again there’s gulf of differences between the two films. Of course, there’s tension between parents and children (in Still Walking) as in Ozu’s film. However, the tension here is of different order. Tokyo Story unfurls in a period when Japan stepped into era of frantic modernity. The old couples visiting their children in Tokyo from the village don’t find any solace in the busy lanes of the city. While Ozu doesn’t villainize the old couples’ children (their tired existence is relatable too) it’s pretty evident how the old people are perceived in the city: obsolete, nuisance, and an embarrassment. In Still Walking, the grown-up children are visiting their old parents on the 15th death anniversary of the family’s most loved eldest son. The children of this generation are too busy with their city lives so as to visit the parents one or two times a year. Nevertheless, considering the shaky global economic climate, the grown-up children are also struggling. The elderly patriarch who worked as a doctor (now retired) is embarrassed by his off-springs. And, all these old and young characters are more vulnerable and angrier than Ozu’s characters.

The greatest thing about Still Walking is that this vulnerability and repressed rage never paves way to heightened drama. Our empathy is shared in equal proportions to all the characters in the film. May be the indelible similarity between Tokyo Story and Still Walking is its quiet, elegiac tone, which despite portraying a very Japanese domestic life, allows ample space to evoke as well as deeply reflect over one’s own familial memories (and also let’s not forget how the death of a beloved family member haunts both films). In the contemporary cinema criticism, there’s the increasing tendency to turn a renowned young film-maker as an heir to an old auteur. For example, calling Christopher Nolan as the successor to Kubrick, or Paul Thomas Anderson as this generation’s Robert Altman or lauding Paolo Sorrentino as heir to Frederico Fellini. While the aforementioned directors have mentioned the old masters as the inspiration, it doesn’t mean that their films rests on the vestiges of yesteryear auteurs. Such tags sometimes doesn’t lead to profoundly approach the great works of current-generation directors. Similarly, I’d love to contemplate more on the uniqueness of Kore-eda’s style rather than offer a discourse on his tributes and influences.

Still Walking opens with the sound of radishes and carrots being grated, onions chopped, and oil sizzling in the pan. The family’s elderly matriarch Toshiko Yokoyama (Kirin Kiki) is preparing the vegetables for the feast as her daughter Chinami (You) listens to cooking tips, primarily to keep company for the mother. The opening scene sets up the ordinary, unrushed family life in rural Japan. The natural light flows through the house and that combined with the non-stop chatter and reassuring cooking sounds evokes our personal memories of the light-hearted family gathering. The patriarch of the family is Kyohei Yokoyama (Yoshio Harada), whose grumpiness has escalated after his retirement from doctor job. He doesn’t acknowledge the conversation of the wife and daughter, walks to the street, and chats with the neighbor, an elderly woman who says her ‘time could be any day now’. The scene beautifully sets up how Kyohei’s fondness for his doctor status (and laments for losing it after retirement) more than the identity of a father or husband. Although the meticulous preparation of food and witty exchanges between Toshiko and Chinami gives the notion of Still Walking being a melodramatic get-together, in the vein of American Thanksgiving tragicomedies, it’s darker and complex layers are gradually revealed with utmost care.

Kirin Kiki’s Toshiko exudes the kind of warmth that’s affixed to matriarch characters. Yet, she isn’t just characterized by her genial, motherly nature. She could be indifferent too. When the daughter asks Toshiko about Ryota (Hiroshi Abe), her younger son, she says “he didn’t have to go for a used model” – referring to Ryo’s recent marriage to young widow Yukari (Yui Natsukawa). She further adds, “It’s better to marry a divorcee than a widow. At least a divorcee chose to leave her husband”. But despite the indifferent comment, Toshiko doesn’t express her resentment to Yukari’s face. The mother’s feelings are driven by old traditional beliefs, which actually don’t make the viewers to judge her. In fact, it provokes us to relate with our parents or other family elders’ corroded old-school beliefs. The joy that marks the mother’s face when preparing the corn tempura and the small hatreds she treasures co-exists to make this well-rounded character. The same goes for other central characters in Still Walking. We can’t really confine them into dual shades of good and bad. In an interview to flavorwire.com, Kore-eda states, “What I wanted to portray with the character of the mother was the idea that you don’t say bad things to people to their face. You wait until they leave the room and you say things behind their back. It’s a principle for her, her philosophy. It’s not limited to just my mother. It’s common to all Japanese people to go through life avoiding confrontation.” Nevertheless, contrary to Kore-eda’s belief, this principle isn’t just specific to Japan; it’s rather universal. In these chaotic modern times, where family or friendly gathering becomes rare, we try to maintain the relationships, however vulnerable it is. It may not lead to evolution or growth in the relationship, yet being overly polite becomes an essential thing.

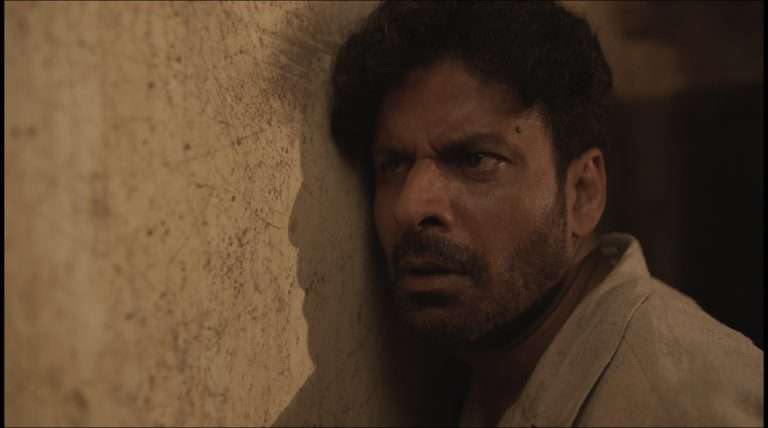

Ryota’s relationship with his father Kyohei is the central aspect of the Yokoyama family dynamics. More than a decade before, the family’s eldest son Junpei has drowned in the beach while trying to rescue a kid. Junpei is the father’s favorite and was expected to carry the medical practice, which is situated in house’s extension wing. Ryota, to his father’s dismay, has chosen the field of arts; partly due to the mixture of hate & envy towards his father’s unbridled love for deceased Junpei. However, Ryota hasn’t become a creative artist. Now in his early 40s, Ryota simply works as art restorer and sometimes goes by the title ‘painting doctor’. He also doesn’t have a steady job which is the last thing he wants to reveal to his parents. The old couples’ incessant mourning for the long-dead son has somehow frayed the relationship with their youngest son. Under these circumstances, Ryota doesn’t very much look up to the gathering. He is accompanied by truly empathetic Yukari and her introvert son Atsushi (Shohei Tanaka). In the train journey to parents’ home, Ryota wonders if they could avoid staying the night by citing ‘emergency PTA meeting’. Yukari frowns and thinks of the gathering as a chance to assimilate herself into the family.

Kyohei and Ryo’s disintegrated relationship is portrayed through a small moment earlier in the film. Ryo and You’s family talk to one another as Kyohei awkwardly enters the frame. Ryota passes off an aloof look, while the others bow. Kyohei immediately leaves the space, loudly locking himself into the small clinic. Every bad thing in Kore-eda’s film has happened before the narrative starts up. His characters are only left to grapple the consequences of the tragedy. And, the tragedy itself is referred in passing conversations and through old nostalgia-inducing objects. Right from Maborosi (1995) to After the Storm (2016), Kore-eda’s characters live in the shadows of a tragedy with no reassurance of a dawn. The conflicts between father and son in Still Walking don’t go through a fixed narrative arc. There’s no ebb and flow in this conflict. Their emotional distance doesn’t need any dramatic revelations. The simple gestures and bodily movements allow us to guess at the conflict that has been thriving for years.

Director Kore-eda states that he had similar difficult relationship with his father, although it was his mother who was against his decision to become a film-maker. Still Walking continues the director’s signature to approach afflicted characters with abundance of empathy. But, this film has few autobiographical strands. Mr. Kore-eda made the film after the death of his mother, whom he took care of in her last two years. The film’s title which hails from the lyrics of a ’60s pop hit called “Blue Light Yokohama” was his mother’s favorite song. Moreover, the attention to detail on the cooking of variety of food items is something he gained after watching his mother’s cooking. “That kind of relationship, where the parent and the child are very out of sync emotionally, it’s very reflective of my personal experience”, Kore-eda says in an article in NY Times. In spite of including the memories of his mother and childhood, Kore-eda doesn’t succumb to sentimentality. He doesn’t breach the characters’ psychology for little emotional drama. Except for the epilogue, the director chooses to limit his narrative within the 24 hours and by doing that he avoids playing the familiar beats about ageing and death. When mother Toshiko is last seen she nimbly crosses the road after sending off her son in the bus and slowly climbs up the steep stairs alongside her husband. Mr. Kore-eda has paid a wonderful homage to his mother through Toshiko’s active existence. Furthermore, by not depicting the mother’s death (and conveying it in simple words), the weight of her absence in the epilogue is much heavier.

The characters in Still Walking, as we know, exhibit incredible restraint. Mother Toshiko and father Kyuhei possess archaic views on re-marrying. Younger son Ryota maintains annoying distance from his parents, asking them to solve the squabbles within themselves. Daughter Chinami intends to move with her family (husband & two children) back to her family home, which may invade the elderly mother’s private space. Nevertheless, the restrained, naturalistic behavior doesn’t allow them to be one-dimensionally defined by the self-centered characteristics or out-dated views. Like us, the characters of Kore-eda are trained to not always express what they feel or think. Perhaps this incredible restraint could be better understood through the conduct of Yukari. The married widow is mostly expressionless throughout the conversations, yet she owns a deeper sense of empathy for the family, despite the in-laws’ insensitive comments about re-marriage and widowhood. On some occasions, Yukari expresses her anger about mother-in law’s rebuffs (when she feels her son Atsushi is snubbed by mother-in law Toshiko), but it doesn’t lead to any over-dramatization. Director Kore-eda is more interested in bringing out the complexities of the relationship between Yukari and her in-laws than trying to design it as simple conflict between old-school and modern values. In one rather uneventful conversation scene, Kore-eda superbly injects the complexities. In the conversation, Toshiko talks about Yukie-san, Junpei’s widow. Yukie-san has re-married, hence she couldn’t be invited. Toshiko wonders If Junpei and Yukie-san had children she would have visited them.

After a perfunctory pause, father Kyohei adds: “Perhaps its better that they did not have children. A widowed single mom is harder to marry off.” The little indifferent remark must have hurt Ryota and Yukari, who are sitting around the Japanese-style dining table. A tense pause ensues. We expect the casual conversation to reach a boiling point, but Yukari counters with a very clever remark. Kore-eda zeroes-in on the conflicts and complexities of the relationship through this conversation and if he had turned it into a shouting match, the complexities would have perished. The other great conversation is the one between Ryota and his mother (Toshiko) which starts from recalling the name of a sumo wrestler and ends up in demonstrating the mother’s pain and hatred after losing her beloved elder son. Toshiko reveals that she wants Yoshio (the boy for whom Junpei gave up his life has grown up to be a fat young man with no promise of a bright career) to visit them on Junpei’s death anniversary, exactly because she wants Yoshio to incessantly feel the guilt of a survivor. Contrary to cinema’s oft-repeated notion, here it is the hatred that helps Toshiko to mourn for her loss. Although Ryota is disgusted by his mother’s candor, a moral dilemma raises in viewer’s mind. While it’s hard to condone Toshiko’s hatred for the innocent Yoshio, it’s also hard to entirely dismiss the deep-rooted grief of a mother.

Still Walking follows certain familiar beats of family gathering movie, particularly the nostalgia factor: The corn tempura, young Ryota’s cute letter about his doctor father, the grimace of a sumo wrestler, the romantic evocation of the hit song ‘Blue Light Yokohama’, etc. However, the nostalgic recollection doesn’t lull the characters into smugness. The random objects in the film are not only used to provoke nostalgia, but also to infuse the realistic environment. For example, the broken tiles and a steel rod in the bathroom speak volumes about the parents’ ageing. The sums and parts of all the little details bring a uniform energy to flow within the narrative. The small details are what the treasures we take away from Kore-eda’s films because he doesn’t keep the conflicts to the fore and peoples in the background. Characters are always at the fore of his works and the details (including human quirks and memory-inducing objects) naturally develops the conflicts.

From the stylistic point of view, Still Walking is different from the largely brooding static shots and takes of Kore-eda’s Maboroshi (1995) & Nobody Knows (2004). As I mentioned earlier, despite assimilating certain Ozu’s themes, Kore-eda deviates a lot from the master Ozu’s sanctified frames. In Still Walking, Kore-eda frequently showcases different generations engaged in polarizing actions across the frames. He focuses on every twitch, pause and laugh that unfolds with in the much-broader frames. Similar to the works of Taiwanese auteurs Hou Hsiao-Hsien (A City of Sadness) and Edward Yang (Yi yi), the director frames the family with all its myriad details and drawing out individual tensions without ever sanitizing their unruliness or chaotic nature. Kore-eda, however, doesn’t forget to keep an observational distance from the family to insist that it’s impossible to capture the whole, well-rounded subjectivity of the chief characters. Although director Kore-eda from his early days as documentarian took on the sociological themes, his restrained manner and empathetic approach of the subjects allows his philosophical notions to take root. He extracts everlasting truths within everyday conversations and Zen composure of the people. We may not understand the Japanese context, but there’s immense space to bring our own context to the things. For example, I don’t have nostalgic yearning for corn tempura, but I can easily substitute it with a delicacy I loved in my childhood. We don’t fully know the belief behind the arrival of yellow butterflies, but it could be related with similar (comforting) superstition in our culture. The scene where Toshiko chases the butterfly inside the house, believing it to be her reincarnated son, is also effective from the visual standpoint. Here Kore-eda follows the mother with a hand-held camera capturing her vulnerability and grief which is otherwise locked deep within her pragmatic, overly polite self. The scene makes us reflect on our own vulnerable activities that’s far different from our rigid external composure. In most of the scenes, Kore-eda also uses random objects to comment on character’s predicament. For example, the distant shot of stranded ship on the shore (towards the end) which is a reflection of the irredeemable gap between father Kyuhei and son Ryota.

One of the predominant reasons for Still Walking’s universal appeal is the director’s focus on the characters’ psychological attributes. We relate with character’s moral dilemmas and emotional complexities because they are flawed like us and their on-screen life becomes a perfect reflection of our own. Despite the cultural and societal differences, some of Toshiko’s traits could be seen in my mother; or I share certain insecurities of Ryota. We can’t just plainly judge Toshiko despite her hate for Yoshio (the boy for whom Junpei gave his life) or the apathetic comments about Yukari (Ryo’s wife). The excessive self-righteousness which kicks to life when watching a cinema disapproves Toshiko’s way of mourning or her traditional beliefs, but Kore-eda gracefully strips off our hypocrisies to profoundly relate with Toshiko and the other characters. From then on, we can understand her and (father) Kyohei’s romanticization of Junpei’s memory or their instinctive comments about Yurkari – calling her as ‘used woman’. They are flawed very much like us – the insecure, ever-lamenting middle-class. Like us, the Yokoyama family too confines their hatred and mockery within four walls of the home. And, as in life Kore-eda has no answer to this anguished existence and his characters are never blessed with an epiphany. In fact, they are too late for that. Yet, the emotional burden which figuratively often pushes me to my knees eases a lot after watching a Kore-eda film. The gulf of cultural divide is bridged upon by the basic emotional reactions, which can bring tears or smiles at the same time to people all over the world, similar to the way our inscrutable, dispiriting emotions are cleansed by great music.

★★★★★

Hirokazu Koreeda — Timeout Interview

Koreeda Interview — Flavorwire

Familial Loss and Proustian Tempura — Dennis Lim’s essay on Still Walking

Contemporary Japanese Cinema Since Hana-bi by Adam Bingham

![20th Century Women [2016] : Southern Californian Bliss](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/20th-century-women-poster-banner-768x292.jpg)