In many ways, Ali Abbasi seemed like just about the ideal choice to helm the first major feature outing on one of our era’s most polarizing figures. After all, the breakout director’s lack of a personal connection to the longtime American personality allowed him to approach the origin story without any sense of personal vitriol. But then again, the world had to collectively live through the geopolitical calamity that Donald Trump emerged to be. How do you make a film about his persona and come across as non-polemic, that too less than a month before his second run for becoming arguably the most influential man in public office?

At the same time, the “Holy Spider” filmmaker has shown his flair (although not fully formed and clever as one might think, in my opinion) in dealing with thematic depictions of disgust and exploitation through his work. That’s to say while his latest, “The Apprentice”, doesn’t feel like an all-out Democrat-funded tactic, it also doesn’t leave much room for intrigue or introspection by resorting to a rather straightforward account of how the worst New Yorker of the 20th century went onto become the most divisive figure of contemporary times.

What we have, then, is a film that lingers between the two extremes, at once acting as a Frankenstein-like origin story while simultaneously compounding the perception of a man who in reality thinks he’s more complex and enduring than he really is. Perhaps, in that scenario, it would make sense why a film about a schismatizing and divisive man would echo the same blemishes along its framework.

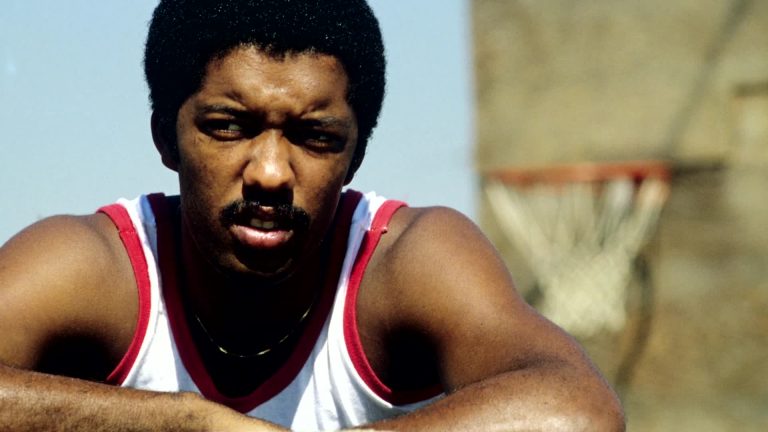

The fictional dramatization here deals with young Donald J. Trump (Sebastian Stan), as the kinetic filmmaking hovers over him walking through the trash-choked streets of Manhattan. From the start, the filmmaking imbues itself in the ’70s styled grainy quality images. His family’s sprawling real-estate business there doesn’t quite mean he’s got things sorted — he knocks on old and mean residential tenant doors to personally collect the rent. But he also has grandiose plans to revive the struggling city in a gamble of making his (self-earned?) fortune.

Donald’s aspirations for reconstructing the Midtown Hotel in his climb to success see hope when he bumps into Roy Cohn (Jeremy Strong, in his form again), a slithery lawyer known for aiding the infamous investigations of the McCarthy period. He’s desperate enough for his breakthrough to follow Cohn into the bathroom to schmooze him into helping him get his famous hotel built. Then follows a chasm of mentor-pupil relationship that paved the way for helping Trump achieve his American dream. In the unfolding of the countless do-overs, business deals, and stiff worker exploitation built over the glittery semblance of optimism he put over his sleeves through the ’80s, we see the nightmare of the American Dream we’ve already seen engulf us in the past eight years.

While taking Trump from grumpy meals in his old family Queens home into the looming corridors of wealth and power, the makers also explore his romance with a feisty Czech model, Ivana (Maria Bakalova). It suggests that she is good for Trump, and perhaps a potential lodestar, unaware yet of the tyrannical side he’d bring even to their relationship. Much has been said already about the movie’s decision and depiction of a graphic scene between them, which would again be counterintuitive to discuss given how mostly everyone watching the film would be coming in with already preconceived notions.

But what’s surprising about everything leading up to that point is how the rather unflattering template of an unflattering figure humanizes the man for who he is. For who he’s always been. While the film encourages you to laugh at his extremes and his often embarrassingly frail vanity, there are also moments of stillness amidst the gonzo excesses surrounding the man. Like, the long take of his face while he presumably sips his first-ever drink to impress Cohn in closing a deal.

The surprise, really, is that it doesn’t come across as exploitative – a complaint I had with the director’s previous film. Here, with the help of his resourceful cinematographer, Kasper Tuxen, Abbasi gets the textured feel of the era right. But more importantly, by not directing the performance in a caricaturist way (credit also to Stan here, who, with this film and “A Different Man,” has shown the extraordinary transformative range he’s got as an actor), he organically makes the terrible behavior seem un-sensational. But the undoing of the film is in how it doesn’t fully embrace its most powerful thematic beat. The film suggests how Trump got his flashy reputation of can-do, will-do at any-cost doctrine from Cohn.

It’s naive and superficial to say so much about Trump while making a movie about him, without letting the dramatics of it inform the perils of populism and neoliberalism. Watching such ethos being planted and fertilized in the young version of a man who paved the way for both makes for fascinating cinema. The fact that we’re supposed to feel sympathy for Cohn as he looks upon the horror that his former friend and client wrought upon him is what makes this a nightmare of the modern-American story. That even one of history’s greatest monsters reaches a point where they’re surprised by someone else’s lack of humanity.

Their central dynamic should’ve been the main lens for this film to channel its urgency, as it hopes to portend something we’re dangerously hurtling toward. Again. “The Apprentice” should’ve served as a portal into that future, instead it remains complicit by drawing yet another portrait of the man who continues to divide us.

![Beneath the Shadow [2020]: ‘NYAFF’ Review – A Slow-Burn Queer Drama That Withers Before Bloom](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/BENEATH-THE-SHADOW-Movie-Review-highonfilms-3-768x512.jpg)

![The Middle Man [2021]: ‘TIFF’ Review – Coen-esque black comedy falls short of its potential](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/The-Middle-Man-1-highonfilms-768x322.jpg)