“No one is more of a slave than he who thinks himself free without being so.”

― Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

In 1947, a Holocaust survivor, Jewish architect Làszlò Tòth, arrived in Philadelphia. Born in Hungary before the war, he was an architect of the Bauhaus school, an architect of works that, in wartime terrain, remain resolutely standing. And who, as in the traditional genesis of men of genius from poverty and misery, will find himself the father of one of the most ambitious projects in his contemporary America.

A library, a cultural center, a church, a memorial. It is an immense, unclassifiable construction, a Brutalist masterpiece, a place of modernity for a modern community. Entrusted by the immoderately wealthy American businessman Harrison Van Buren (Guy Pearce), the architect is to design a building honoring the recent death of his mother. The project will absorb 30 years of Làszlò’s life, meticulously observed by camera master Brady Corbet, and it is the story of a man who, like the film’s author, seeks to create art out of the impossible.

Corbet’s film, shot in 70 mm, is a nearly four-hour odyssey, before all else, beautifully crafted. Tòth’s relentless pursuit of the architecture of beauty is transposed into a filmmaking that seems to have already grasped and mastered the secret of this quest. In fact, every sequence and shot starring the architectural genesis and its components is millimetrically gorgeous. Visually splendid, “The Brutalist” is describable in the words of its protagonist: “Beauty made of only what is necessary.” Or, from another character’s perspective, “the necessary beauty to tolerate what (or who) one would otherwise despise.”

Indeed, there is enough beauty to please Von Buren’s tolerance, which makes little effort to conceal a claim of superiority toward blacks, Jews, and foreigners in general. Toward the beggars at the station, who make it indigestible. Toward drug addicts, the impoverished, the weak, and those who, in one way or another, seem not to embrace the Western aspiration of the American dream. Von Buren is the prototypical fake humanitarian, always ready for acts of altruism, only toward those who, on a scale of values he defines, make themselves worthy of his benevolence. A scale of values according to which Làszlò, a visionary Jew, is a tolerable foreigner. Consequently, his wife, the brilliant Erzsébet (Felicity Jones), and his niece, the taciturn Zsófia (Raffey Cassidy), are also affected.

More than a story of brilliance, “The Brutalist” is a portrait of the ‘stranger in a foreign land.’ In this case, the experience of Jews who, after World War II, were reduced to the status of beggars. Taking up Goethe’s quote, which is referred to in the first few minutes of the movie, it is a reflection on how to be free is not simply to consider oneself as such, especially in a world where individual freedom is defined chiefly within the terms of calculated external altruism, as shown not only in Làszlò’s relationship with Van Buren but also with his Americanized cousin Attila (Alessandro Nivola).

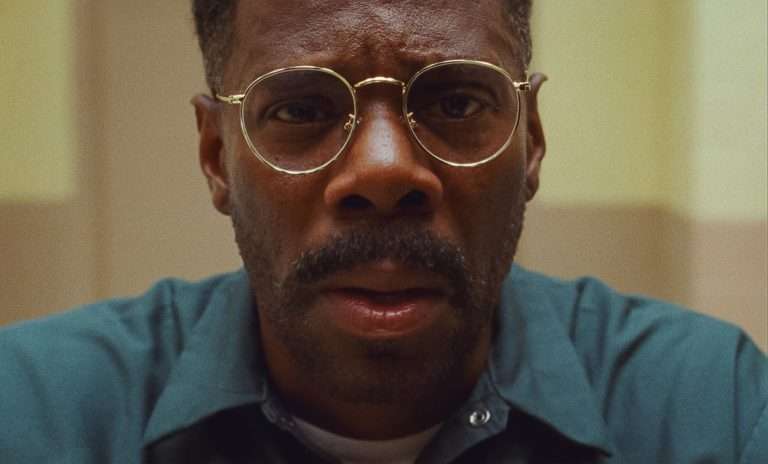

The acting performances are, without exclusion, excellent. Leading actor and constant presence throughout the film, Adrien Brody, extraordinarily inhabits the role of Làszlò, his neuroses and vulnerabilities. Similarly, Guy Pearce convincingly plays the role of the wealthy American self-portrayed deity, just as Felicity Jones shines in what is usually a second-rate character, that of the ‘protagonist’s wife,’ which becomes the movie’s heart. Equally convincing is the rest of the supporting cast, from Joe Alwyn and Stacy Martin as the Van Buren’s offspring to Raffey Cassidy (and her depiction of trauma in her character Zsòfia) to Alessandro Nivola and Emma Laird (as Mr. and Mrs. Attila and Sidney Miller).

However, the real, major stumble of “The Brutalist” is probably to be found in its runtime. The 215 minutes of the film appears unwarranted mainly, if not by the authorial will, to achieve such a length of viewing. This is apparent mainly in the second act, where the pace becomes waning and unsteady, failing to maintain the fluidity of the first 100 minutes. The narrative also suffers, moving in a somewhat unclear direction and in a circular repetition of events and situations interspersed with sequences that appear borderline random.

In particular, the evolution of the dynamic between Làszlò and Harrison, potentially the film’s highlight, suffers, in its conclusion, due to an unsatisfactory and hurried execution. At the same time, the gradual overload of thematic input, though rich in insights, leads to a final simplification of the overall story as the only solution to the enormous narrative complexity achieved. The bizarre and didactic epilogue constitutes another shortcoming of the nevertheless excellent movie, especially if compared with the stunning opening sequence.

On the other hand, the technical department is excellent, from the sound (Steve Single and Szabolcs Gàspàr) to the set design (Judy Becker) and the costumes (Kate Forbes), as well as the soundtrack by Daniel Blumberg. A faux biopic, relevant as ever in the modern landscape (and despite its less successful features), “The Brutalist” has the potential to emerge as a modern classic and to be remembered as an absolute achievement in Corbet’s filmography.

![A Family Tour [2018]- ‘NYFF’ Review](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/a-family-tour-hof-768x432.jpg)

![Ashes and Diamonds [1958] Review – A Wartime Story Told in Bold Visual Terms](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Ashes-and-Diamonds-1958-768x470.jpg)

![County Lines [2019] Review: A gut-wrenching tale of a teenager peddling drugs](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Country-Lines-1-highonfilms-768x576.jpg)