The 1997 cult favorite preys on our most internal fears: Very early on in Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s horror film “Cure,” there was a scene that already had me reaching for the rewind button. A slow pan across the beach, where a man is squatting and furiously sketching on a notepad. Another man enters the frame, and suddenly, the sand seems to shift color from a glistening beige to a pallid greyish-green, like blood draining from the face. Of course, it’s an illusion caused by clouds drifting past the sun, but it’s also symbolic of the dark and malevolent shadow that will soon envelope the psychological landscape as well.

The two men exchange a few words, and it’s clear this intruder is an amnesiac. The artist tries to talk further with this mysterious man, inviting him home to see if he can help him reclaim his memory. His altruism will be rewarded a short while later by the murder of his wife…at his own hand. The artist attempts suicide, but it is too late; the amnesiac’s experiment has succeeded, and he will find more victims. And his victims will find victims of their own, as well…

A director obviously can’t control the clouds the way they can their actors, but through sheer luck, Kurosawa was able to instigate a visual motif that will recur throughout the film. The shadows wafting over the sand will be hauntingly echoed at various points as the story unfolds. Blood slowly pooling over the concrete. Water from a spilled glass darkening the marbled flooring in a hospital room. Another drop of water hits a lighter, splashing pitch-black fluid over a grainy wood table. Each time, either right before or right after a sudden scene of shocking brutality, or even both (the brutal murder of a sex worker takes place just before the beach scene) we witness a metaphor for the darkness creeping over and enveloping the human soul, as outwardly normal, even kind-hearted people are driven once again to commit acts of great evil.

Each of these murders may have different perpetrators (at least we think so at first), but are united by the killer’s inability to remember committing them and the presence of an “X” carved out on each victim (a cinematic motif that originated with Howard Hawks’s “Scarface” and would be echoed again by Martin Scorsese for “The Departed”). Assigned to investigate is gruff detective Kenichi Takabe (Koji Yakusho, a long way from his star-making turn in the previous year’s “Shall We Dance?”), who has enough troubles of his own: his wife Fumie (Anna Nakagawa) is being treated for schizophrenia and is starting to lose her memory, being in the early stages of dementia.

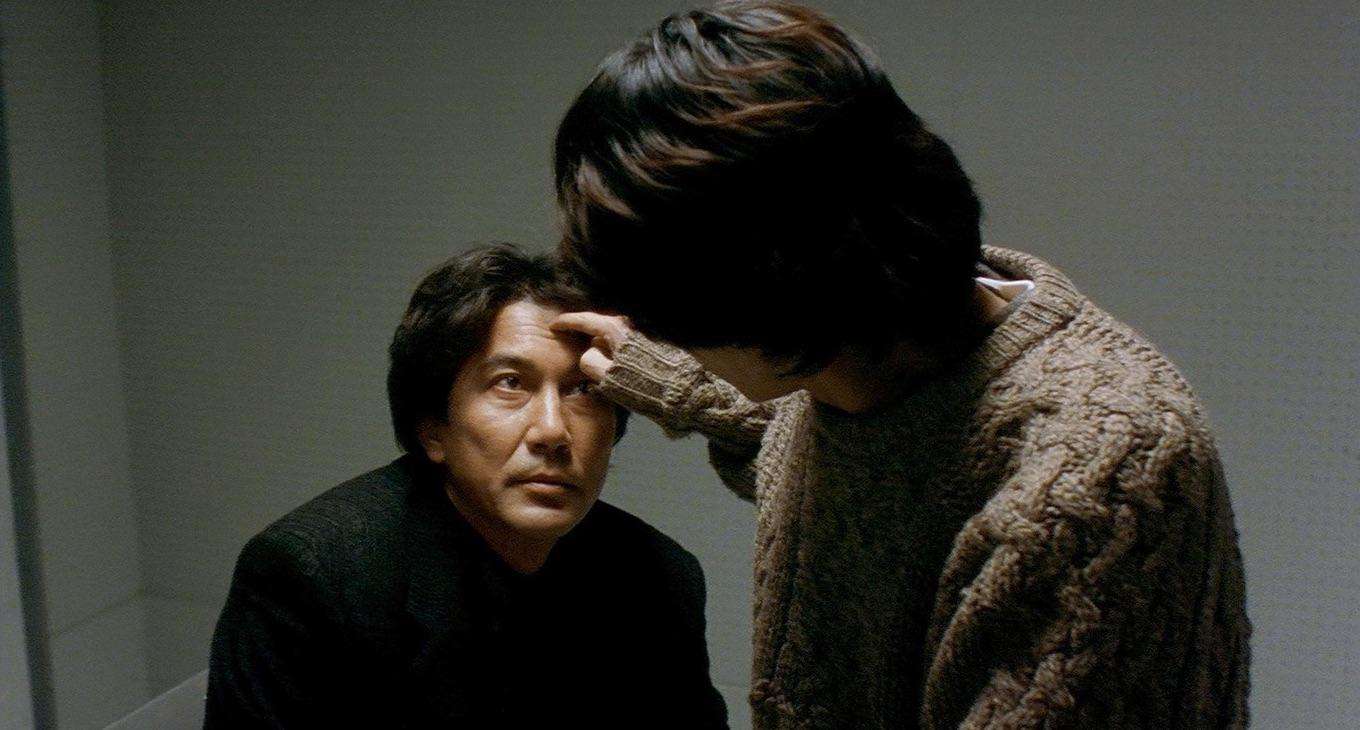

Accompanied by psychologist Sakuma (Tsuyoshi Ujiki), he tracks down the one person uniting all the murders: Mamiya (Masato Hagiwara), the same gangly, hairy-lipped amnesiac encountered at the film’s opening. In most horror films, the capture of the monster (human or otherwise) signals the triumph of good over evil, an explanation to wrap everything up and the end of the terror at hand. Here, at least for the main characters, it’s just the beginning.

It’s tempting to call “Cure” a horror film had it been directed by Yasujiro Ozu, and granted, there are strong stylistic similarities: both Ozu and Kiyoshi Kurosawa rely on both long takes and long shots alike, frequently taken from a stationary camera situated at floor-level and within a horizontal frame, a highly elliptical editing scheme and the absence of a traditional score. And yet, there are also major differences in directorial technique that reflect Kurosawa’s more pessimistic yet no less sympathetic take.

For one thing, Ozu was known for including much activity going on off-frame in a given scene or implying that it was continuing outside the shot. If a character exited the frame, his camera would remain stationary and continue to linger on the empty screen. Frequently, when concentrating on action within the frame, Ozu would make clear there was additional activity going on right outside of it, made perceptible by outside dialogue or barely discernable movement occurring just beyond the margins.

In stark contrast, Kurosawa restricts all his action to that which is confined within the current frame, and uses tracking shots throughout if he needs to depict additional activity. If a character starts to walk to the edge of the screen, the camera moves with them, creating a feeling of continual surveillance and confinement. This technique seems distracting at first, but it’s essential to communicating the key themes of the film. Ultimately, both Ozu and Kurosawa are concerned with human loneliness and the toll it takes not just on interpersonal relationships, but to the wider spectrum of society itself. At least in this one film, Kurosawa seems as preoccupied as Ozu with a psychic malaise afflicting Japanese social and family life, one that can easily be recognized by any viewer no matter where they live as existing within their own communities as well.

While many other films prey on our fears of being alone, Kurosawa instead takes a different tack, taking advantage of our fears of loneliness itself. There’s another particularly indelible image in “Cure” reflecting not just these fears but the tensions arising from them: that of a monkey pacing frantically back and forth in a narrow cage, obviously greatly distressed and suffering from starvation and neglect in its cruel confinement, surrounded by other similarly caged animals. We later learn that Mamiya had been experimenting on these lower primates before moving up to people, and Kurosawa similarly uses this one as a human proxy himself.

The characters in the film are in an emotional and psychological situation not unlike that of the poor simian, not just trapped within the horizontal borders of the camera frame, but subject to stresses caused by interpersonal and social isolation that makes them easy prey for a psychic predator to take advantage of them. They have had social and psychological barriers placed between themselves and others, are starved of affection and other emotional needs, and are forced into dull work routines that numb their empathy.

As a result, they are unconsciously building themselves into an interior frenzy, ready to be unleashed once the right catalyst finds them. Takabe himself is subject to the same pressures: the stress of watching his wife slowly disintegrate and his fears of inevitable loneliness take a toll on him, and the pain is only exacerbated by the horrors uncovered over the course of his investigations. When he, too, erupts in violence, it may be less brutal, but it is no less terrifying.

Alfred Hitchcock made a similar analogy in “The Birds” to caged avians and the human characters, trapped within social and psychological cages, their own frustrations about to be released violently as well. One also recalls Norman Bates’s famous lines in Hitchcock’s “Psycho,” penned by Joseph Stefano: “I think that we’re all in our private traps- clamped in them. And none of us can ever get out. We — scratch and claw, but only at the air — only at each other.” The characters in “Cure” also scratch and claw at the air until “freed” from their cages. And then they can only do so at each other with fatal results.

This is true of our leads as much as it is with the characters who are manipulated into murder. In this context, Mamiya’s actions seem even more cruel; he is not just coercing others into murder but taking advantage of their mental and emotional isolation to wreak social havoc (supposedly, the loneliness theme is even more prominent in Kurosawa’s follow-up “Pulse,” which I have not yet seen).

While the presence of a book on Franz Mesmer in Mamiya’s home has been noted by many, the full title often goes unmentioned: Mesmer and the End of the Enlightenment in France. Mesmer, for the uninitiated, was a late-eighteenth century pseudoscientist who put forth bizarre notions of “animal magnetism” and whose name lent itself to the terms mesmerism and mesmerize, synonyms not just for hypnotism but to have one’s will and mental attention subverted to another’s gaze. As nonsensical as Mesmer’s ideas were, they were taken quite seriously in their time, and its similarities to the later and similarly medically dubious notions of Reiki expounded by Mikao Usui in Japan a century later have been pointed out by scholars of quackery.

Even though the French Enlightenment was associated with the extolling of Rationalism, Mesmer’s decidedly irrational notions had found followers within it, compelling then-King Louis XVI to convene a panel to examine its claims. This team of investigators, which included Benjamin Franklin, Antoine Lavoisier, and physician Joseph-Ignace Guillotin, found no scientific basis for it, and Mesmer was forced into exile. A decade later, both the King and Lavoisier would be dead, murdered under the blade that bore Guillotin’s name (against his humanitarian wishes) by the revolutionary fanatics of The Great Terror. Mesmer’s revenge? Maybe Mamiya thought so.

Related to Cure (1997): 6 Movies to Watch if You Liked ‘Longlegs’

Perhaps Mamiya also imagines himself as being not just a modern-day Mesmer but a 20th Century Robespierre, instigating his own reign of terror and encouraging a casual acceptance of mass murder among an outwardly sane and reasonable populace. But from the evidence we see on film, we have already exited the Age of Reason, and Mamiya is only accelerating the process. The character of Sakuma is often forgotten in analyses of the film, yet he has a very important thematic role.

Both he and Takabe are united by their commitment to a rationalist and methodological approach and have been trained to treat each case as dispassionately and objectively as possible. But this case not only shatters their relationship but their very faith in the ideals they have lived and worked by for their entire lives. For Sakuma especially, whose training and commitment to reason could not prepare him to deal with the horrors he had to confront. There is a complete inability to cope with this intrusion into the rational world he believed in, and hence his ultimate fate.

Kurosawa claims to have been influenced primarily by classic American horror films, yet beyond the aforementioned Hitchcock inspirations (and citing the influence of Hitchcock on a thriller seems as redundant as mentioning how a Western film seems inspired by John Ford), little of that influence is immediately apparent in “Cure.” That is not to say one can’t see similarities to certain definitive films in the horror and thriller genres.

Mamiya’s modus operandi invokes the villains played by John Barrymore in “Svengali” and Charles Boyer in “Gaslight,” and despite the bloody scenes the film itself is very much in the subtle, low-key tradition of Val Lewton’s psychological horrors, with an ending that recalls the depressing conclusion of “The Seventh Victim.” That film deals in part with an underground cult that tries to compel recruits to kill themselves in a similar manner to the way characters in “Cure” are driven to murder, again implicitly by another malevolent cult intent on social disruption.

The presence of a Japanese translation of Helmut Barz’s retelling of “Bluebeard” recalls Edgar Ulmer’s classic 1948 film of the same title (which bears little actual resemblance to the original French story), long the favorite “Poverty Row Horror” of the art house crowd. In that film, John Carradine’s gentleman puppeteer and painter is prone to sudden psychotic fits in which he brutally murders young women, not unlike the ordinary citizens suddenly turned killer in “Cure.” Another movie it surprisingly resembles is the 1932 sleeper “Thirteen Women,” in which Myrna Loy takes revenge on her former sorority sisters by hypnotizing them into suicide, although it’s doubtful Kurosawa had seen it before making his own film.

While it came out at a time when serial killer movies overran American theaters, Kurosawa’s film is a very different beast from most of them. There certainly are major stylistic and thematic differences between it and the two most well-known movies in the subgenre, Jonathan Demme’s “Silence of the Lambs” and David Fincher’s “Se7en,” despite the similar subject matter. Whereas both of those are very dark films with a gritty and grimy look used throughout, “Cure” is deliberately filmed in bright, high-key lighting with an antiseptic feel to even the goriest scenes. Demme’s film, with its emphasis on intense close-ups and other directorial choices that try to emphasize the connections and kinships between the various characters, is very much in opposition to Kurosawa’s with its aforementioned emphasis on long shots and dwelling on the emotional loneliness and isolation amongst its own dramatis personae.

Some have also perceived thematic affinities with Fincher’s film, possibly the most nihilistic ever produced by a major American studio, but the toxic misanthropy of “Se7en” is totally at odds with the sympathetic approach taken by Kurosawa in “Cure,” who treats each murder as a tragedy for all those involved. His attitude is as pessimistic as Fincher’s and every bit as uncompromising, but it is a more civilized savagery, the type of despair that manifests itself in tears instead of screams or sickness. There are also scenes early in the film that are reminiscent of Michael Mann’s “Manhunter,” but Kurosawa gradually transitions to a completely different visual and editing style as the story develops and new themes unfold and reveal themselves.

The one American film it really seems to fully resemble, in terms of story, theme, and stylistic choices alike, is Larry Cohen’s cult item “God Told Me To” (1976), a sloppier, less coherent but still fascinating film in its own right. Cohen’s film is also structured as a police procedural, following another detective (an excellent Tony Lo Bianco) who is also trying to figure out why so many seemingly sane and law-abiding individuals have suddenly committed terrible acts of murder. His investigations also lead him to a similar guru-like figure (Richard Lynch) possessing great power to influence others, although this character’s background requires an even greater suspension of disbelief. It all ends on a similarly pessimistic note, with the “hero” turned murderer himself, and the open implication that the chaos has not ended.

“Cure” was largely overlooked in North America when first released there in 2001, not experiencing the commercial success of such later Japanese horror films as “Ringu” and “Audition” upon their subsequent release to world markets. It certainly didn’t help that its American distributor went bankrupt shortly after its stateside release or that the aforementioned glut of serial killer movies in the ’90s had left American audiences fatigued, if not totally desensitized to such films.

It has since proven to be the sleeper success of the “J-Horror” trend of the late Nineties and early Noughties, especially after Bong Joon-ho declared it one of his all-time favorite films in the 2012 Sight and Sound poll and it received high praise from Martin Scorsese as well. Amidst this growing prestige, it was eventually released on Blu-ray by the Criterion Collection in 2022, yet it still remains an unseen film for even many knowledgeable horror fans, and many of those who do herald it do so in muted terms.

The best explanation I have for this is that it does not try to scare audiences in the traditional way, nor does it take the contemporary route of trying to disgust or disturb the viewer through explicit or shocking imagery. Of course, some will disagree with me, because they were scared by the film or disturbed by some of the gorier scenes (I still flinch just thinking about the face-peeling scene, which rivals that in “Eyes Without a Face”) but it’s trying for something deeper, more probing of the audience’s psyche.

Plenty of horror and suspense films have exploited our fears that our neighbors, our family, and even our closest friends might be hiding deep, dark secrets within themselves, but Kurosawa also exploits our fears of the evils hiding within our own selves, even if we deny them. Of course, this is hardly a completely original theme; the various adaptations of “Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde” as well as “The Wolf Man” and most subsequent werewolf movies have all famously dealt with it. What makes Cure’s treatment of it particularly disturbing is its matter-of-fact approach, suggesting we only need the slightest nudge to push us to the brink of evil.

If there was a single overwhelming feeling throughout my first viewing of “Cure,” it was a feeling of oppressive sadness. It’s a sensation I had only felt once before from a horror film, from Werner Herzog’s “Nosferatu” (1979). For that matter, the only other horror film (if one can call it that) of recent years that left a similar sensation of utter tristesse was David Lowery’s “A Ghost Story” (2017), which similarly also builds on the fears of solitude even within a social human landscape.

I felt sad for the murder victims in “Cure” but also for those manipulated into committing such awful acts. I felt deeply for both Takabe and his wife and Sakuma as well. Somehow, I even managed to have a twinge of sympathy for Mamiya, who, instead of being the epitome of “evil incarnate” as described on the Criterion website, I came to regard more as a pathetic child than an outright monster. And at the very end, I felt great sorrow for everyone. There was no cure for their madness…or for their loneliness either.

![Jesus [2019]: ‘Japan Cuts’ Review – The dilemma of belief through the prism of innocence.](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Jesus-Japan-Cuts.jpg)