In his continued quest to adapt all of August Wilson’s plays to the big screen, Denzel Washington has firmly placed himself squarely in the producer role, handing off directing duties to those who could do with the spotlight. After his own successful outing with “Fences” and George C. Wolfe’s relatively equivalent success with “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom,” Washington has set his sights towards an incoming visionary at the bottom of the Hollywood food chain, with no other avenues of potential exposure… Just kidding, he handed “The Piano Lesson” off to one of his sons.

Now before you scoff at Washington embracing the time-honored tradition of industry nepotism and giving the reins to the less famous of his two boys (while the more famous of the two takes on the leading role), consider this: with the incredibly high standards set by his father’s legacy—and an older brother who already has a head start carving out his own—Malcolm Washington might have nearly as much to prove as an artist as his father once did. With “The Piano Lesson,” Malcolm crafts just about the most dynamically directed adaptation of Wilson’s work yet.

Produced by a Washington, co-written and directed by another Washington, and starring yet another Washington (for the sake of clarity, each Washington will henceforth be referred to by their given names), “The Piano Lesson,” like most Wilson adaptations, functions largely as a chamber-piece, confined to the post-Depression Pittsburgh home of Doaker Charles (Samuel L. Jackson). It’s here that his nephew, Boy Willie (John David Washington) and his friend Lymon (Ray Fisher) find themselves after a drive up from the family’s native Mississippi to sell a truck full of watermelons. Boy Willie has a plan: to sell those melons and gather enough money to buy a plot of land from the property of the family that once owned his own.

Those melon funds won’t be enough to pay off the land, though, so Boy Willie has his sights set on another fundraising opportunity to close the gap: selling the meticulously carved piano that his own father died smuggling out of their former slave master’s house. This doesn’t sit well with Boy Willie’s sister Berniece (Danielle Deadwyler), intent on keeping the heirloom right where it is. Her attachment isn’t helped by the fact that the ghost of the former slave owner, Sutter—only recently deceased under suspicious circumstances—seems to be hanging over them, in more than just a metaphorical sense.

This last bit more or less primes “The Piano Lesson” for a certain ingredient that would give it a vastly different flavor from the previous Wilson adaptations, themselves at risk of monotony in a sea of endless, static theater adaptations: a flair for psychological horror. Malcolm, for his part, proves himself wonderfully adept at manipulating his sound and frame in order to solidify the tightening tension that manifests when familial friction makes way for the supernatural. In no scene is this clearer than a joint song between the men of the house, in which a moment of sorrowful solidarity becomes punctuated by increasingly ominous and forceful foot stomps and creaking floorboards. (Alexandre Desplat’s robust score also proves instrumental (pun intended) with regards to the consistent borderline-horror tone of the film.)

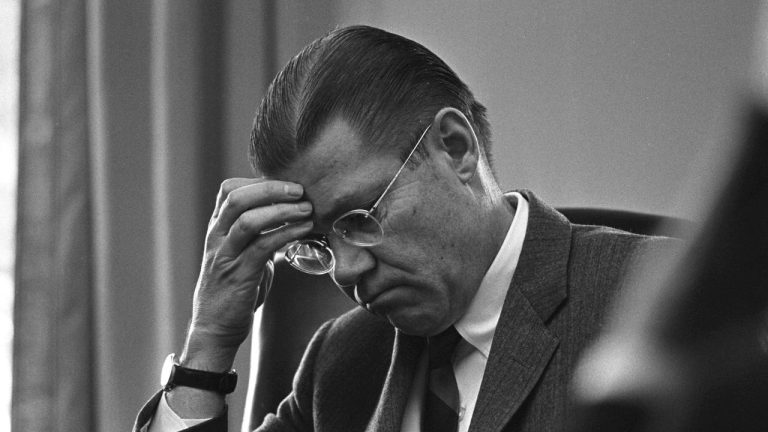

The tightness of craft is matched by an intensity in the film’s performances—John David doing his best to channel his father’s charisma, Deadwyler getting ferocious to the point of near-overkill, and Jackson basically disappearing into the background to occasionally react to something someone else has said—which gives “The Piano Lesson” a particular vantage point in quantifying the institutional racism that has plagued African Americans through the ghosts (both literal and figurative) that follow them around when attempts are made to carve out a future beyond the scope of their ancestral bondage.

Malcolm and co-writer Virgil Williams mine from Wilson’s material a tangible sense of frustration evolving into vigorous tension between Boy Willie and Berniece, and the director’s continuous dynamism with the camera and editing keeps that tension as high as it can be, even when the pacing begins to sag. Unfortunately, “The Piano Lesson,” at two hours, struggles to maintain that momentum without relegating itself to a series of occasionally tiring monologues, passionately delivered as they may be. As a result, there comes a point when the balance between that supernatural allusion and the more grounded familial melodrama begins to falter, before regaining some footing as Malcolm’s play at atmospheric direction pulls in some overtime in the last act.

That “The Piano Lesson” manages to be a compelling piece of filmmaking in its craft, beyond the delivery of solid performances, already puts it in a league above most theater adaptations on the market right now. Far too many of these films, including the past Wilson adaptations, struggle to find the right equilibrium of lively technique and actor-friendly restraint (a lesson Stephen Karam, for instance, took too far in the opposite direction with his adaptation of his own play “The Humans”), but Malcolm Washington demonstrates a focus well above the scope of a debuting filmmaker. With further focus given to that balance of tone, we could be looking at a true talent behind the camera, well worthy of his family name.

![Always Be My Maybe Netflix [2019] Review: A Comedic Treat with a Racial Flair](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Always-Be-My-Maybe-2-768x432.jpg)