In the frenetic landscape of contemporary cinema, dominated by fast-paced narratives, bombastic special effects, and relentless sensory overload, there has emerged a counter-current going by the name of “slow cinema.” Film scholar Emre Çağlayan, in his book “Poetics of Slow Cinema,” defines the phenomenon as a particular subgenre of filmmaking whose aesthetic features include “a mannered use of the long take and a resolute emphasis on dead time.” The deliberate pacing and minimalist aesthetics of these films, however, are not merely stylistic choices; they reflect a profound philosophical engagement with time, perception, and the human condition.

Slow cinema challenges the contemporary viewer’s investment in the rapid-fire information intake characteristic of the late capitalist world and, instead, invites them to reclaim the act of looking: to linger on details, to savour the unfolding of time, and to engage in a more mindful and introspective relationship with the cinematic experience. The camera becomes a patient observer, lingering on a sun-drenched kitchen as hands rhythmically knead dough or capturing the wind-swept solitude of a shepherd traversing a desolate plain. Such seemingly uneventful scenes, however, are not devoid of drama or tension. Instead, they simmer with a slow-burning intensity, where unspoken emotions flicker in glances, and the weight of unspoken words hangs heavy in the air.

In this article, we explore the landscape of slow cinema by discussing ten great films from around the world that foreground stillness, each for uniquely different reasons; films where time slows down and lets us rediscover the profound in the mundane, reconnect with the rhythm of our own lives, and find meaning in the silences between words and actions. Enjoy.

“I despise stories, as they mislead people into believing that something has happened. In fact, nothing really happens as we flee from one condition to another . . . All that remains is time. This is probably the only thing that’s still genuine–time itself: the years, days, hours, minutes and seconds” – Béla Tarr

1. Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975)

Chantal Akerman’s magnum opus is an intimate portrait of three days in the life of a widowed mother, Jeanne Dielman (Delphine Seyrig). Shot entirely with static camerawork and featuring unhurried editing, the film takes an intent look into the ritualistic nature of a housewife’s monotonous existence as Jeanne’s carefully calibrated system slowly starts to fall apart. Akerman shows no interest in dramatizing this woman’s daily routine with cinematic techniques and decidedly risks boring the viewer to death with the 3-hour-plus runtime. Yet this precisely is the point: foregrounding the oppressive mundanity that’s often part and parcel of what it means to be a woman, giving it concrete meaning by letting it be experienced in real-time instead of cutting up the action at a thousand places as in conventional filmmaking.

The film’s glacial pace trains the viewer to register and react to the tiniest fluctuations and nuances in the action, heightening the senses. One wouldn’t expect to be watching a 3.5-minute static shot of a woman just kneading and folding a lump of meat to prepare meatloaf and still be in thrall of it if not for the hypnotic quality Akerman achieves. With a largely flat and frontal cinematography that places us squarely inside Jeanne Dielman’s living room and her kitchen (and her life), the film becomes a subtly powerful commentary featuring scenes neglected in conventional cinematic representation. Akerman made it clear that the film was responding to the “hierarchy of images” found in mainstream cinema, where certain eventful images (like a kiss or a car crash) are prioritized over images of cooking or washing up, the latter belonging to the sphere of domesticity traditionally associated with women.

2. Landscape in the Mist (1988)

Driven by their mother’s stories, young Voula (Tania Palaiologou) and her brother Alexandros (Michalis Zeke) flee their Greek village in search of their unknown father in Germany. Along the way, they encounter both fleeting kindness and crushing betrayal, their innocence withering with each icy blast. They fall into the care of a benevolent puppet troupe led by the gentle Orestis (Stratos Tzortzoglou). Here, amidst the colourful spectacle, a semblance of normalcy flickers, but the yearning for their father pulls them away, urging them towards the unforgiving road. The world outside the troupe is harsh and unforgiving. Trust turns to betrayal as a truck driver exploits their vulnerability, leaving Voula with a searing scar of trauma. Hunger gnaws at them, the biting wind mocking their thin, threadbare coats. The dream of Germany and their father figure, once vibrant, starts fading into the mist.

Greek director Theo Angelopoulos paints a hauntingly ethereal portrait of childhood disillusionment and yearning in “Landscape in the Mist.” The film is shrouded in a perpetual mist, both literal and metaphorical. Hazy, wide shots blur the edges of reality, adding to the sense of uncertainty and displacement. The vastness of the Greek countryside is often captured in long, static takes, emphasizing the vulnerability of the two children against the indifferent immensity of nature. Rugged mountains, desolate highways, and sprawling industrial complexes become daunting obstacles in their journey. Did they find their father? The film’s silence is deafening, leaving only the echo of their transformative journey and the poignant beauty of hope facing harsh realities.

3. Satantango (1994)

A dying collective farm in a rain-soaked Hungarian village. The villagers await a promised payout, their dreams flickering in the face of grim reality. Irimias (Mihály Víg), a presumed ghost, returns with promises of a utopian commune, his motives as murky as the mud beneath his feet. Mr. Schmidt (László feLugossy), a conniving husband, plots to steal a promised cash payout, igniting a web of deceit and betrayal. As trust crumbles and hope evaporates, Irimias’ commune reveals itself as a cruel mirage, leaving the villagers stripped bare emotionally and financially. Following a final act of treachery, the promised land dissolves into a desolate wasteland, reflecting the moral hollowness that festered beneath the surface of their collective hope.

Béla Tarr’s seven-hour-plus “Sátántangó” transcends any straightforward plot summary: it’s an immersive experience meticulously crafted through deliberate formal and stylistic choices. Tarr’s signature technique lies in his mesmerizing long takes. The camera, often handheld and sinuously gliding, follows characters through their mundane tasks, drunken binges, and tense confrontations. We aren’t merely observing; we’re living and breathing alongside the characters, feeling the mud squelch under our boots and the icy rain stinging our faces. Tarr masterfully manipulates light and shadow: the interiors are often plunged into near darkness, illuminated only by flickering candles or shafts of cold, grey light. Mihály Víg’s haunting score, with sparse piano chords and mournful strings, reinforces the film’s melancholic atmosphere. “Sátántangó” is a bleak tapestry of human despair, where hope and ambition come to drown in the downpour of shattered dreams.

4. Few of Us (1996)

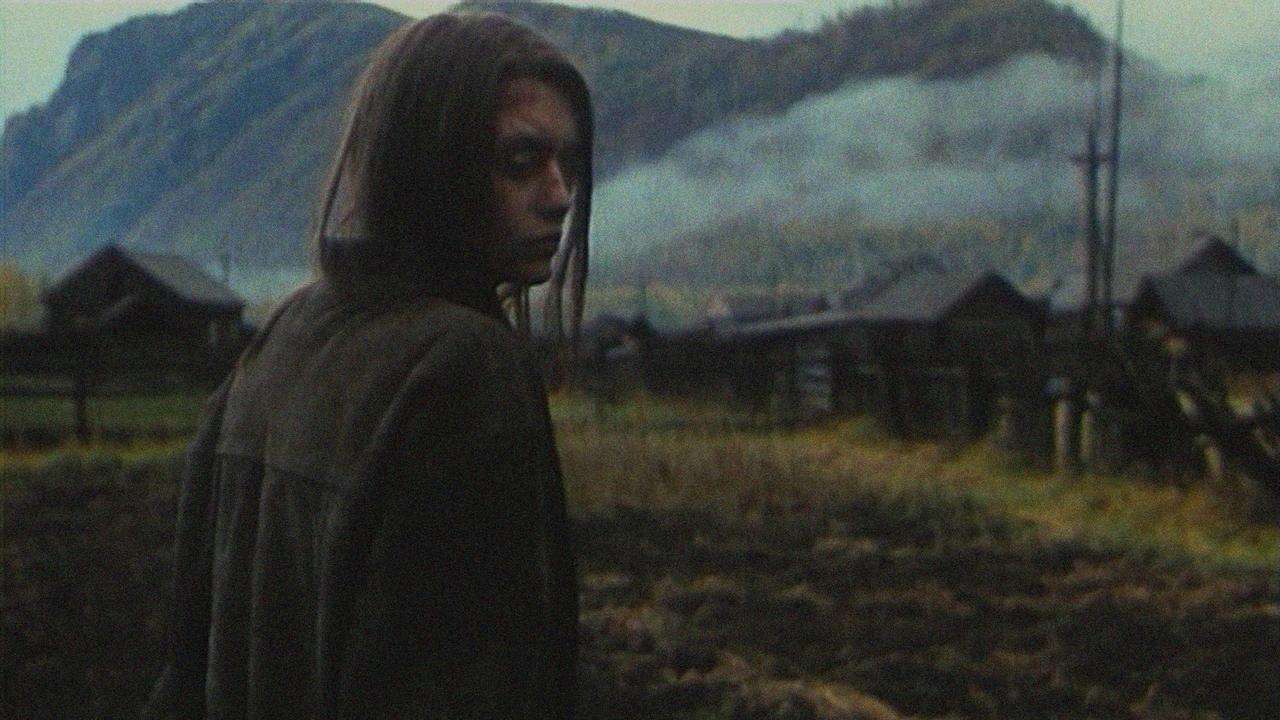

From Lithuanian director Šarūnas Bartas comes this moody meditative piece where a young woman visits the nomadic Tofalar tribe in the Sayan Mountains of Siberia. Yekaterina Golubeva (also Bartas’ spouse) in the leading role is a sight to behold, with her sunken blue eyes radiating tenderness and melancholy. She seems to be seeking refuge within this indigenous community that’s secluded from the rest of the world and keenly observes the daily rhythms of the inhabitants’ lives. There is no well-defined plot or character arc to speak of, and little is revealed about the woman’s motivations or thoughts, allowing (and even encouraging) us to fill the blanks with our interpretation of the images presented.

Additionally, there’s no dialogue throughout “Few of Us,” resulting in Bartas’ trademark minimalism being distilled to the purest essence of the cinematic apparatus – visual storytelling. Steadfast long takes govern this dreamy painting of a film which, almost paradoxically, incorporates distant long shots alongside moments of intimacy, training the viewer along the way to glean information from gazing eyes and furtive glances. Bartas’ camera zooms up close to study faces and tiny fluctuations in their expressions, lounges back in contemplation to observe people going about their daily business, or just quietly absorbs the sublime serenity of the vast, awe-inspiring landscapes. The predominance of silence, along with images carrying the additional communicative burden of words, provides an unparalleled level of immersion within this alien world we find ourselves navigating and makes for a soul-cleansing cinematic experience.

5. Evolution of a Filipino Family (2004)

Filmed over ten years and with a runtime of over 10 hours, Lav Diaz’s “Evolution of a Filipino Family” illuminates the unseen face of a nation spread across its past, present, and projected future. The fragmented, nonlinear narrative – as if being recalled from memory – charts the gradual descent of an impoverished family in a remote Filipino barrio and is juxtaposed against real historical events depicting the various atrocities committed in the name of President Ferdinand Marcos, who placed the entire country of Philippines under martial law for 14 years. It soon becomes apparent that the ‘Filipino family’ in the title refers not just to the characters in the film but also to the history of the larger nationwide family.

Diaz mixes archival footage alongside scripted sequences to emphasize the sociopolitical context from which he derives the fates of his characters. He freely uses dead time to let us lose ourselves within the rustic sights and contemplate the events we witness, often placing shots that serve little narrative purpose other than to firmly settle us within the shoes of his characters. This is an invitation to not just watch but LIVE alongside this Filipino family, sharing their sustained experiences and emotions, which essentially means sharing time with them. Instead of cutting away every few seconds to accelerate the narrative, Diaz encourages us to take a long and hard look at these humans, and the million little ways that they’re slowly and silently crumbling away.

As we see one man stabbed in the belly, lurching and stumbling forward to his death for 20 minutes straight on empty streets flanked by empty dysfunctional factory buildings, it manifests as a bleak yet inescapable image of a nation rushing to its demise. Time alone can transform hunger into starvation, anxiety into fear, and hopelessness into crippling depression, and experiencing the lives in this poor cursed barrio means experiencing time on their terms, which precisely is facilitated by the 10.5-hour-long “Evolution of a Filipino Family.”

Also, Read: Lav Diaz’s Tale of Decay and Hope in “Norte, the End of History”

6. Le Quattro Volte (2010)

Michelangelo Frammartino’s “Le Quattro Volte” (The Four Times) presents a uniquely contemplative account of the transmigration of the soul across the four Pythagorean realms – human, animal, vegetable, and mineral. It opens with a few men burning charcoal inside a huge kiln – an image that’d return at the end of the film, thus completing its “dust-to-dust” existential cycle. We see an old goatherd (Giuseppe Fuda) and his dog as they go about their regular day-to-day, most of which involves tending to the large herd of mountain goats. Suffering from an ailment, every night, the goatherd is seen taking his “medicine” – a handful of dust from the nearby church dissolved in water.

One day, the man loses his medicine, and following a bizarre sequence of events, we find him on his deathbed, surrounded by his goats. The goatherd’s demise signals the film’s transition into its second act, which cuts to the birth of a goat (as if a transfer of souls has taken place), the narrative now following this animal’s perspective. Soon, we find the goat lying down under a majestic Fir, which becomes its final resting place as seasons pass from winter to spring, and its existence merges with that of the tree.

Eventually, the tree is chopped down to decorate some local ritual, and then, its cultural purpose exhausted, is sent off to be turned into charcoal. The burning charcoal turns into smoke, billowing out of the chimneys and making its way up to the heavens, concluding the Pythagorean cycle of birth and death. Frammartino’s vision, as realized in this dialogue-free film, is indifferent to conventional hierarchies imposed upon the living and non-living – treating men, animals, rocks, and trees all with the same degree of deference, the indistinct murmur between humans as unintelligible to us as the bleating of the goats or the rustling of leaves.

7. Two Years at Sea (2011)

Structured as a docufiction, British filmmaker Ben Rivers’ “Two Years at Sea” traces the Scottish hermit Jake Williams living in complete isolation within some unspecified frozen region surrounded by a forest. There’s no dialogue, obviously, given that there’s no other human to talk to, and the whole film hinges on the many little ambient sounds and noises that accompany this man’s day-to-day existence. Shot in grainy black and white 16mm film (and blown up to 35), the cinematography captures the beauty of the barren landscape juxtaposed against the solitude of the man’s existence, with long takes and lingering shots contributing to the overall atmosphere of stillness.

We see Williams going about his daily rituals as he cooks, reads, builds a shelter, and browses through photos, aside from navigating the unique challenges of living in such a remote location. Ben Rivers creates a sense of tranquil timelessness that grabs hold from the very first few frames and refuses to let go till the final credits appear. Away from the maddening din of human civilization, the film is a genuine breath of fresh air that’s as sublime as it is therapeutic to the soul.

The centerpiece of “Two Years at Sea” is a nearly 8-minute-long unbroken shot showing the man quietly getting on his raft and floating across an icy pond. As simple and sparse as it may sound, like the scene itself, this description utterly belies the experience one has when encountering it within the film. Ultimately, it is this experience facilitated by the film that becomes far more important than any interpretation of its text, as aptly noted by Manohla Dargis: “What counts is the fog that wreathes the trees, the bloody folk song that the man plays on a record player, the slight pulsing quality of the images and the way that another person’s seclusion can feel like an oasis.”

8. Stray Dogs (2013)

Tsai Ming-liang’s “Stray Dogs” revolves around a tiny, fragile family of three – a father, son, and daughter grappling with extreme poverty. The father (Lee Kang-sheng) works a back-breaking job as a human billboard, standing in the middle of the unforgiving roads of Taipei, constantly buffeted by the cruel winds of the world. Tsai quietly follows this family as they wander around, scrounging for food and shelter and whatever scraps of happiness they can find in this joyless world. He films the stagnation and decay that govern their existence amidst haunting visions of a happier and more functional family life – without any clear indication as to whether these visions are relics of the past or dreams for the future.

With long static takes, Tsai paints a cripplingly bleak picture of the vastness and weight of the world, reducing the powerless little family to insignificance: with images like that of a huge tree (taking up most of the frame) dwarfing the two kids in front of it, followed up by the camera lingering on the father struggling to get his heavy boat off the shore with an extraordinary amount of effort. The title derives its significance when we see the family eating out of discarded cartons of expired food dumped outside a supermarket, the same cartons that were used moments ago to feed a pack of stray dogs. Juxtaposing both excess and lack in a single image, it stands emblematic of the key concerns of the film – the advent of neoliberal capitalism and the accompanying dehumanization of its most precarious subjects.

9. Horse Money (2014)

Pedro Costa’s fourth feature dealing with the lives of Cape Verdean immigrant workers residing in the Fontainhas slums, “Horse Money,” is centered around Ventura – the quasi-patriarchal figure introduced in Costa’s previous film “Colossal Youth” (2006). Through endless dark corridors and cavernous rooms, the lone Ventura traverses the length and breadth of his people’s past, forging a truly one-of-a-kind exploration of personal and political history. He has been hospitalized and seems to be suffering from an aggravated case of dementia and nerve damage, his fingers trembling uncontrollably, conjuring up ghosts from a bygone era – faces and names belonging to his friends and family.

The film is astonishingly dense despite the languid pace, with a lifetime of pain and agony breaking forth every passing minute while barely allowing us enough time to process it all. One unforgettable sequence involves Ventura being trapped inside an elevator with what seems to be his conscience, which has taken the shape of his fears: a freedom trooper in uniform. The figure alternatingly echoes voices from his past – his wife, his friends, and his people from Fontainhas – as Ventura makes his final ascension upwards, in prison stripes, having finally acknowledged all his past crimes and negligences.

Trying to piece together a fractured memory and thus exorcise his demons, Ventura leads us on a haunting journey across decades of oppression heaped upon these Cape Verdean immigrants – an impoverished working class that survived years of exploitation and, finally, a revolution that only complicated their problems. With long static takes absorbing every detail and spellbinding chiaroscuro threatening the impregnable darkness of these lives and frames, “Horse Money” almost doesn’t appear to be set anywhere on our familiar green Earth, but rather in some obscure realm buried deep within the recesses of Ventura’s unconscious.

10. An Elephant Sitting Still (2018)

Four lives crisscross and collide with one another under the gloomy sky of a small Chinese town, setting off an uncontrolled chain reaction that would irreversibly transform their damaged existence. 16-year-old Wei Bu (Peng Yuchang) is on the run after an altercation with the school bully escalates to dangerous proportions. 60-year-old Wang Jin (Li Congxi), Wei’s neighbor, finds himself suddenly unwelcome amidst his son’s family, who’d rather drop him off at some nursing home. Huang Ling (Wang Yuwen), Wei’s classmate, lives precariously with her irresponsible mother while nursing a secret affair with her school’s Vice Dean. Yu Cheng (Zhang Yu), the school bully’s reckless older brother, is caught in a web of revenge, responsibility, and guilt after witnessing a tragic event that he may have unwittingly caused.

We patiently follow the four lives through the course of one eventful day of simmering tension, punctuated by bouts of violence and feral rage. All of them are drawn to the news of a circus elephant sitting still in Manzhouli all day long, refusing to eat or move as if completely detached from civilization. What do these four broken souls, battered and bruised from life’s cruel blows, seek from this mythical elephant? Perhaps they see within the beast’s deathly stillness a reflection of the stagnation and existential crisis that afflicts their own lives. Or maybe the elephant just functions as their North Star, catalyzing their escape, guiding them together towards a new life – away from the asphyxiating clutches of their past misfortunes.

The film grips you from the start with its sense of immediacy and nihilistic outrage and sustains the tension through long takes governed by the camera moving with zen-like calm and precision, intent close-ups, and slow focus pulls that alternate emphasis on the humans and the bleak environment they’re trapped within, and a sparse background score evoking foreboding and melancholy. Deliberately paced, with a mammoth 230-minute running time, “An Elephant Sitting Still” is the bold debut feature of Chinese novelist-turned-filmmaker Hu Bo, a protégé of Béla Tarr. Unfortunately, it is also his final work, with the 29-year-old Hu killing himself only weeks after finishing the film.