Buoyed by a recent string of critically acclaimed films, Vietnam’s cinematic landscape is buzzing with fresh energy. A new generation of talented filmmakers might usher in a new wave, with their works gracing prestigious international stages. Director Trương Minh Quý’s “Viet and Nam” exemplifies this exciting trend, weaving a poignant tapestry of love and loss that is sure to captivate audiences.

The film opens with the introduction of two male protagonists, Viet and Nam, who are laborers in a coal mining area. Beyond the coal dust and gritty atmosphere, the focus shifts to Viet and Nam, who are isolated and having a peaceful time together. The way Viet and Nam converse with one another provides a certain level of comfort. The director’s masterful touch lies in the quiet power of understatement. This subtlety creates a pervasive sense of serenity throughout the film. It’s a stark contrast to the immersive, almost trance-inducing style of Andreï Tarkovsky, where pacing itself transports us to a hypnotic state. The narrative revolves around Viet and Nam’s journey as they navigate their lives alongside each other and encounter multiple tribulations.

The director inserts the exploration of gay relationships through the eyes of Viet and Nam exclusively. The depiction of love is intimate and secluded rather than swamped by heightened sexual fantasies. Aside from the covert nature of their relationship, it appears that neither the community nor their family is oppressive. Although there are indications that Nam’s mother is aware of their relationship, she would rather remain silent and still extend an invitation to Viet for dinner. Viewers would start to comprehend Vietnam’s lenient views on homosexuality, which has never been a reason to oppress any individuals.

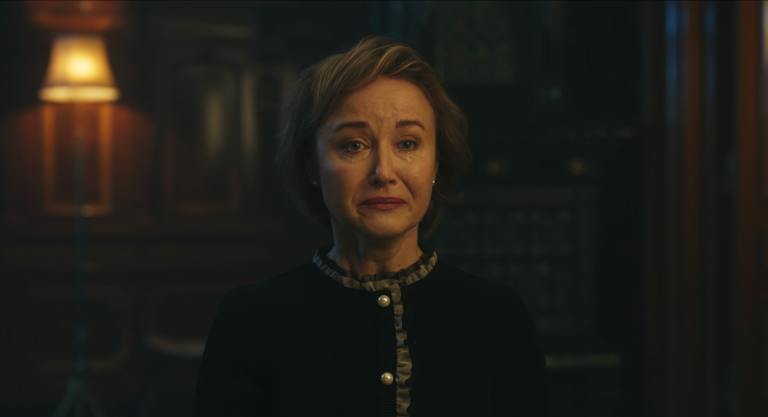

In terms of context, the political backlash of exile and death has affected their families continuously in different ways. The effects of war have diminished the harmony of the nation, where many unclaimed bodies of martyrs are announced on air. This takes me back to a scene in Pedro Almodóvar’s “Parallel Mothers,” where Janis Martínez (Penelope Cruz) and her family are seen in tears as they grieve over the buried bodies of loved ones. The atmosphere is very much similar in this film, where grief is felt through the silence and gentle weeping of the people.

We get a glimpse of how the community has not healed from these deaths, as many have experienced the unexpected loss of a loved one to the point that they are constantly looking for closure. At this juncture, the filmmaker focuses on the concept of cultural and supernatural beliefs as a survival mechanism. For instance, Nam’s mother, driven by the hope of finding her husband’s remains, embarks on an unconventional quest for the truth. She delves into the depths of her dreams, searching for clues buried beneath the surface of consciousness.

The mother believes that her dreams bring her closer to her husband. Furthermore, we observe their reliance on psychics to recall the deceased’s last moments and provide clues as to potential burial locations. The director employs a unique approach here: reenactments based on the psychic’s visions and messages from the community. This allows viewers to piece together the events surrounding the husband’s death. Nam is transported to a recollection of his father’s possible death in the war as he pursues a forest route that leads him to a hidden hole. He reenacts the death scene as a form of memory projection, which is perhaps one of the film’s most notable scenes.

Viewers are taken to a surrealistic realm of conceivable truths through the usage of metaphoric messages woven within Nam’s mother’s lullabies and recollections of the past. A notable scene in which a veteran informs Nam’s family of his fear of consuming frog meat is a clear example. Here, the war veteran describes how frogs typically emerge from corpses as a sign of a dead body after a war. This eerie belief takes on new meaning for Nam as he follows a frog to a hidden opening. Interestingly, the director carefully inserts metaphorical hints into every aspect of the film, drawing comparisons to Phạm Thiên Ân’s “Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell.”

Numerous puzzling yet important questions start to surface as the film progresses. Why weren’t appropriate safety measures implemented in the mining sites to ensure the workers’ safety? Do mining workers receive adequate wages for their arduous labor and risky working conditions in hazardous areas? How could Nam’s mother have been so sure that her dream would lead her to her husband’s grave? Despite having a close relationship with Viet, why is Nam so keen to leave the country? Is the psychic merely using her gifts to attract the town’s attention, or is her truth helping the community come to a peaceful conclusion? Is the problem of illegal immigration still present in Vietnam today?

The film’s technical aspects are enhanced by Félix Rehm’s editing, which takes advantage of the film’s dual structure. “Viet and Nam” is split into two sections, one centered on Viet’s romantic journey with Nam and the other on the search for Nam’s father’s body. The film’s fragmented narrative, masterfully crafted by the director, invites viewers to become active participants. The audience forms their own interpretation by piecing together the story’s scattered pieces, deepening their engagement with the film’s themes. The film’s sound design by Vincent Villa is another pillar of strength, capturing the aura of being in the vicinity of rural Vietnam in its purest form. The genuine portrayal of two men seeking love amid misery masterfully brought to life by Đào Duy Bảo Định as Viet and Phạm Thanh Hải as Nam earns them a round of applause.

This year’s UnCertain Regard nominee, “Viet and Nam,” is a gritty, surrealistic, yet absorbing drama that explores the impact of love against the backdrop of war. “Viet and Nam” resonates deeply with its cultural roots, exploring the enduring grief and profound respect for the nation’s lost veterans. The director appears to be redefining the term “buried” in three distinct contexts: the buried love between two men, the buried body of a loved one, and the buried coals as a symbol of arduous labor. If you were captivated by the magical aspects of “Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell,” you would be equally stunned by the beauty of “Viet and Nam.”