In One Battle After Another (2025), Paul Thomas Anderson contorts and reframes the myths of the American West to tell his most politically pertinent and emotionally driven story yet. Paul Thomas Anderson’s obsession with the past has been a recurring topic in recent years. For two decades, he’s luxuriated in it, mining it for nostalgic highs and operatic lows, staging American epics and personal dramas on ecstatic canvases.

And, in recent releases, whether it be the hazy psychosexual malaise of “Inherent Vice” (2014) or the shabby pot-smoke-stained romanticism of “Licorice Pizza” (2021), we’ve burrowed deeper into his brain, resulting in films that feel like chewing gum caught in the diary of a director, each slowly distancing him from the world he inhabits.

With “One Battle After Another,” this has changed. To some, this marks a refocus on the present, suggesting that Anderson is finally dealing with the here and now. To me, his latest effort is as steeped in nostalgia and historical reflection as he has ever been. It is a film that is just as much about reckoning with a past that refuses to stay buried as it is about navigating modern America.

Anderson hasn’t made a film set in the 21st Century since “Punch-Drunk Love” (2002). Yet, that film, in part about discovering the power we have over our lives – capturing a man’s realisation that he can escape sadness and fly towards the thing he truly wants, like a moth to a flame – was staged in such other-worldly quirk and angst, that it feels much less tied to a specific time, than to a specific, timeless feeling.

Time isn’t the only thing spiritually bonding “Punch-Drunk Love” and “One Battle After Another.” With both, Anderson taps into our need to love and, by that same virtue, fight for that love. Adam Sandler’s Barry defeats bad guys and henchmen, punching drunk like some cartoonish Superman, and Leonardo DiCaprio’s Bob tries (and often fails) to fumble his way to his daughter’s aid. Both are driven by pure pursuits, not just escaping frustrated mundanity, but chasing paternal or romantic love.

Differing from the insular and intimate frame of “Punch-Drunk Love,” Anderson’s latest is an almost 3-hour pulse check on modern America. It is a film about the form that societal battles take and the fragile conditions in which these are won or lost.

What’s most interesting is not what Anderson depicts, but how he chooses to depict it: the structure, framing, and timing feel both deliberate and urgent. In an age defined by conflict, fatigue through conflict, and lack thereof, Anderson asks a difficult question: how do you tell the story of a nation at war with itself? Anderson finds his answer via the framework of the American Western, a cinematic form that has always been America’s great battleground of history, ownership, power, and morality.

Anderson uses the Western mythic framework to dissect modern America. The Western genre framework itself is a hybrid. Although Western genres originally influenced Japanese samurai films, they were later absorbed by their aesthetics and themes in turn — a reciprocal borrowing that Anderson both acknowledges and reimagines. What better framework to capture the capitulation of the American dream, which has collapsed inward and spewed out violence across the political spectrum?

Read: The Last Frontier Is Us: What ‘Eddington’ and ‘One Battle After Another’ Say about Survival in the Current Global Order

For decades, filmmakers have reimagined the mythologies of the past. As far back as the 70s, American Westerns like “Little Big Man” (1970) and “Soldier Blue” (1970) confronted history and challenged perceptions. This extended beyond the Western: the grizzly grunt of Rambo questioned US imperialist and interventionist attitudes, and in “Point Break” (1991), a band of bank robbers wore masks of former US Presidents in a knowing mockery of an imbalanced and elitist capitalist system – a system which favors the Lockjaw’s of the world.

In “One Battle,” Penn wears the sagged and tired faces of the Trump administration’s leading henchmen like a metaphorical mask, an inversion of imagery that is as in-your-face obvious as the plastic mask-wearing dress-up that Bigelow used all those years prior.

In “One Battle,” we’re ushered into an off-the-grid America, where underground communities survive through togetherness and unity. This is interwoven with a father–daughter tale of dysfunction led by Bob Ferguson (Leonardo DiCaprio), a former demolition expert-turned-revolutionary, who has spent fifteen years fortifying walls to protect his daughter (Willa) from the world he once tried to change. His paranoia echoes real-world border raids, ICE roundups, and family separations, where private dread and public violence blur.

Fifteen years from his halcyon days of revolution, Bob is now affected by paranoia and protective, denying his daughter a phone, guarding her from the law he’s spent the last decade and a half evading. When it inevitably arrives in the form of Sean Penn’s Colonel Lockjaw – jackboots, boners, warts and all – he is forced to confront it.

Complementing the father-daughter tale is an odd love triangle orbiting Bob’s ex-revolutionary lover, Perfidia, the subject of desire for Lockjaw and the film’s symbolic site of control. A lingering question of paternity fuels Lockjaw’s fixation, driving his pursuit of Willa as he seeks to confirm whether she is, in fact, his. Beneath this twisted and racially driven obsession is the question of ownership. Anderson mines the Western’s colonial foundations to expose how the toxic impulse to own and the urge to possess – land, women, power – metastasizes into paranoia and fascism.

Lockjaw is an absurd and terrifying presence – face convulsing, muscles bulging – a steroidal military relic who lurches across the screen like a Freudian man-baby. In moments, you almost feel sorry for him. The performance recalls “Mickey 17,” where Mark Ruffalo gave a cartoonish Trump impersonation that split audiences. Here, Penn takes it further. Lockjaw plays like an RFK Jr. archetype, bloated with conspiracy and bursting at the seams.

In the film’s opening, he growls and grunts like a warped, underbelly impression of Clint Eastwood, the Marlboro Man reimagined as a grotesque mannequin. Walking like a defunct robot, he is an oversized paradox, at once absurd, terrifying, and hilarious, and precisely the kind of figure who thrives in the heightened morality of the Western, where character has always been more archetype than realism.

In one of the film’s defining images, Lockjaw (his jaw now unlocked and obliterated by a shotgun) returns from the dead, staggering across a sun-beaten plain. Indefatigable and grotesque, his persistence itself becomes mythic: the past refusing to die, history marching back over the horizon. Woven into the film’s cinematic grammar and narrative is this sense of the horizon as threat, as promise, as inevitability.

In Bob’s frantic pursuit to rescue his daughter, further archetypes of the Western are mimicked. The trope of the damsel in distress, seen in Westerns such as “The Professionals” (1966) and “The Searchers” (1956), is turned on its head. This change-up isn’t exactly new to the genre. As recently as Maclean’s “Tornado” (2025), we have come to expect ideas and imagery to be flipped and reassessed in modern cinema. Only Anderson is the first to mangle, contort, chew up, and spit out these ideas to such a degree.

Via the traditions of the Western, Bob’s hopeless pursuit to save his daughter should also culminate in a face-off with Lockjaw, a showdown that the villain naturally craves. This isn’t just narrative logic for Lockjaw, but ideology, the “man-to-man” solution, a fantasy of order that sustains his worldview.

The duel is the expression of his backward psyche, and it’s only natural that this should manifest in twisted paternal fixations, racial obsession, all culminating in an obedient adherence to the damsel in distress archetype. Despite this, the face-off never materializes. Save for a brief comedic exchange in a supermarket, Bob and Lockjaw never come to duel, the image of the sheriff and the outlaw, the ronin and crook; the Jedi and the Sith, never comes to fruition.

Read More: All Paul Thomas Anderson Movies (Including One Battle After Another), Ranked

Instead, Lockjaw’s confrontations are reserved for the film’s women. Perfidia upends the traditional power dynamic of desire, and Willa targets Lockjaw’s fragile and insecure sexuality, power, and manhood. Even Bob and Lockjaw’s supermarket encounter is blurred by Lockjaw’s racially charged obsession with Perfidia, leaving Bob a confused observer rather than an active antagonist. By rejecting the duel, Anderson also rejects the Western’s moral geometry. Old certainties collapse, and the torch quietly passes to a new generation.

The dynamic between Bob and Lockjaw is abstract, elusive, and unclear. One is chasing shadows, the other chasing ghosts. Neither truly confronts the battle at hand; they are fighting mirrors while the real revolution happens under their feet. While “Punch-Drunk Love” gave its audience the catharsis of the fight and the fist-pumping success of the stand-off, “One Battle” refrains from this satisfaction; ultimately, theirs isn’t the battle that matters. It is an archival fight, no different from the reruns of “The Battle of Algiers” that Bob indulges in. Their battle might as well be in black and white, or, as Anderson posits, it should be unclear and meandering, a cat chasing its own tail.

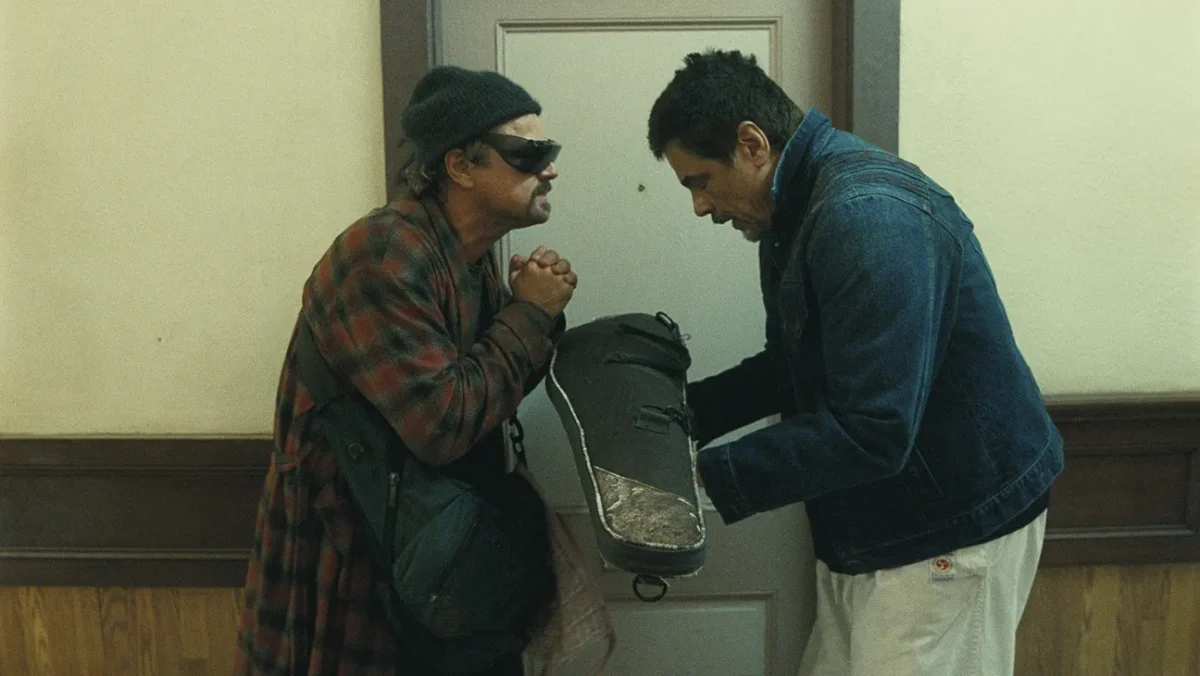

It’s also pertinent to note that Benicio Del Toro’s ‘Sensei’, an underground revolutionary and Willa’s fighting instructor, is the only character we see truly saving lives. But this happens quietly and out of sight. Hidden from the shouty stand-offs of white figureheads is a real fight, a battle that matters, whether this be communities in the suburbs or a pot-smoking superfluity in the sticks, a fight can only be won in numbers, in unity, and in selflessness.

“One Battle” is a film in which the past, present, and future seem to coalesce, ultimately landing in the beating heart of public paranoia and dread. Over the past year, new films have carried recurring themes of inter-generational conflict or connection. In Zach Cregger’s “Weapons,” a witch desperate to hold onto her youth is torn apart by a horde of screaming kids; in “Happy End,” the film’s optimistic tone was propelled by two moments of older generations sharing music.

Then there’s “One Battle,” where a paranoia-afflicted Dad attempts to shelter his daughter and eventually learns he no longer needs to do this. By the film’s end, she is encouraged to fight. Anderson dramatizes the generational passing of responsibility much as the Western has often staged one era giving way to the next.

Another film released this year, which tapped into similar social fears and took advantage of traditional Western genre foundations, is Ari Aster’s “Eddington.” The difference: “Eddington” screamed our anxieties back at us like a late-night doom scroll, whereas “One Battle” offered us action and next steps; it demonstrated the freedom that is inherent in the fight. As the film itself says, the fight is bigger than me, you, and everyone.

“One Battle” culls the misanthropy of “Eddington.” Instead, Anderson opts for optimism, a message of empowerment for his family, which is precisely the tone that gives the film its strength. While the title may suggest endless struggle, Anderson insists that the fight itself is the point, the proof of life, the guarantee that history can never fully be owned or ended.

“One Battle After Another” is not just a film about paranoia, or fascism, or even America. It is a film about the inevitability of history itself, the battles that refuse to die, and the necessity of confronting the past rather than endlessly replaying it. That Anderson stages this reckoning, in this political context, within America’s most haunted genre, is precisely what makes “One Battle After Another” his most significant and culturally relevant film to date.