“It’s a disease. Nobody thinks or feels or cares anymore; nobody gets excited or believes in anything except their own comfortable little God damn mediocrity.”

Richard Yates, Revolutionary Road

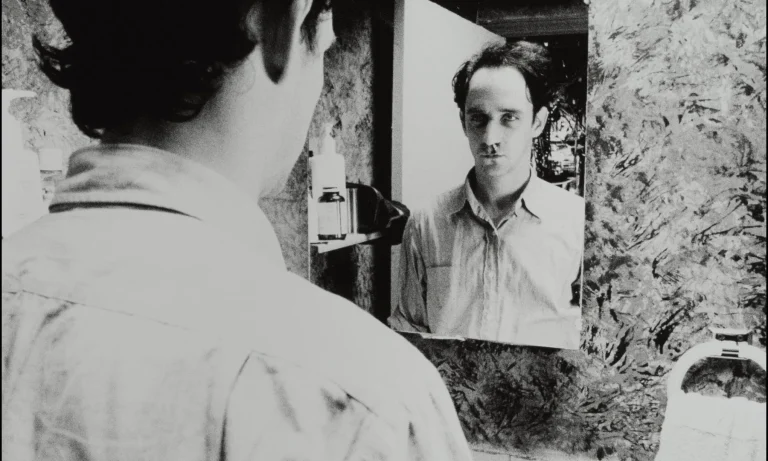

SE7EN (1995) is a timeless classic and one of the pivotal genre films of the last three decades. The gripping subject matter and the “What’s in the box?” twist are just small contributors to it. A jarring and disturbing watch, the film exposes us to our own hypocrisy. Directed by David Fincher and written by Andrew Walker, on the surface, Se7en has a very simple story: two detectives, one a meticulous veteran and the other an impulsive greenhorn, team up to catch a serial killer who is using the seven deadly sins as his modus operandi.

Se7en (1995) still remains one of the greatest films of the 1990s, which continues to stay relevant. Morgan Freeman plays Det. Somerset, who finds that apathy is the only way to cope with the cruelty of the world around him, while Brad Pitt plays Det. Mills, young and hopeful at the state of the world, believing he can make a difference.

Movies have long mirrored and mimicked society. But for all its hideousness, one would be hard-pressed to find a city as unflaggingly grotesque as the innominate one in the movie. The script does not establish a particular locale for the story. The city is a character in itself. It is unnamed, forever swamped in the rain, and has an unending number of dark corners (exemplified by the many low-angle takes and cold and dark color palettes). The city is cold and unforgiving, crimes go unsolved, and empathy is responded with ridicule. In my numerous rewatches of this classic, the city always reminded me of another famously languid city with ample crime, malversation, hopelessness, and despair. Gotham. The city has a history of mental illness in the lion’s share of its population, and people commit horrendous crimes that have no purpose. It has a very Gotham-esque vibe to it.

Related Read to Se7en (1995): Every David Fincher Film Ranked

Alfred Hitchcock famously said, “The more successful the villain, the more successful the picture.” and the same is the case for Se7en (1995). In any good story, villains are the catalysts who move the story forward, challenging the audience (by challenging the protagonist) to own up to their actions. John Doe’s intelligence and passion for his plans, coupled with his prudence and scrupulousness, is what makes him great. George R. R. Martin said, “Nobody is a villain in their own story. We’re all the heroes of our own stories,” and you see that happening with John Doe.

As you find out more about him, you start to understand him. He makes you uncomfortable because the people he killed sometimes disgusted you, too. But he also knows that he is not above any of the sinners that he has punished (even if not for the same reasons). He knows he must be punished as well. So when the movie ends with his plan being successful, you are, to some extent, despite being despondent, understand the logic of it, too. We, as humans, tend to take advantage of things that seem convenient to us. We are complicit.

While Se7en (1995) deals with the seven deadly sins of gluttony, greed, pride, lust, sloth, envy, and wrath, evocating the dread of mythology and symbolism, which John Doe uses as his motivation for committing the murders, the biggest sin throughout the movie is something else. Apathy. Apathy is the emotion of denial. It is the antithesis of empathy. The citizens of Se7en’s city are doused in apathy. The absence of feeling and passion is so profound that they accept it as commonplace. The murders form a pattern over the course of the narrative, which encompasses Somerset and Mills. The killer constructed the pattern to provide a wake-up call to society’s inhabitants, and the film intends the same for its viewers.

Social critique is at the heart of this story and peeks out in various instances. The inhuman police work (interest only in the mechanics of crime-solving without looking further), the hostile and disconsolate surroundings (constant downpours), the resignation of others’ problems by people (complaining about the noise rather than calling the police or the landlord of the ‘sloth’ victim being oblivious to the crime happening in his building as the rent was paid on time). Somerset sees crimes of hate, aggression, and murder and people’s reactions to them daily.

Seeing people plainly ignoring and not caring about fellow humans makes him wonder what is wrong with society. Something incredibly shocking has dissolved into a quotidian, and regular activity and apathy have become the common response of society toward events that should be considered shocking. Having lost faith in humanity, Somerset adopts cynicism and apathy as his primary defense mechanism. An emotion he shares with John Doe, who said, “We see a deadly sin on every street corner, in every home, and we tolerate it. We tolerate it because it’s common, it’s trivial.” They both share a distaste for people’s apathy.

While John Doe certainly takes his philosophy to an extreme level, ‘hitting them with a sledgehammer just to make them listen,’ the point he makes is not a flawed one. The point is we as a society have become apathetic to a fault. Doe has an issue with the casualness with which people accept sin, which renders virtue meaningless. He is bent on teaching humanity the errors of its way as he blames society for letting these sins run wild and corrupt everyone.

He is convinced that the growing apathetic nature of the people leads to the deadly sins corrupting the world and driving it into further meanness and self-absorption. The utter lack of care or concern for others, both in the police and the general public by extension, conjoined with the ending that has the villain emerge victoriously, leaves the viewers in despair. However, the film argues that people must abandon apathy as a solution to the problem of the epidemic of human suffering.

Also, Read: Some Unconventional Movies to Watch to Satiate the Movie Buff In You

In Se7en (1995), Brad Pitt’s character asks pertinent questions that make Freeman’s Somerset answer them, further necessitating him to examine and elucidate them. Thus, Somerset, who initially sympathized with people who chose apathy as a survival mechanism, arrives at the epiphany after vigorous ideological arguments that a belief system that justifies apathy is not beneficial to anyone, including the ones clinging to this philosophy. He realizes that apathy not only leads to suffering but that others’ suffering can cause suffering to himself. His philosophy failed to even serve him. Mills thus emerges as the philosophical antagonist to Somerset, making him question and ultimately change his point of view.

The libretto makes a case that beliefs that absolve apathy are more harmful than beneficial to society. Somerset, whose mind was afflicted by despair and who decided to leave the force because he didn’t think he could “continue to live in a place that embraces and nurtures apathy as if it were a virtue,” decided to stay back as he realizes that the fight to ward off the evils of the world comes from within else the sin will take over the indifferent populace, in no short part to Mills’ opinion on his chosen philosophy “You say ‘the problem with people is that they don’t care, so I don’t care about people.’ That makes no sense… The point is that I don’t think you’re quitting because you believe these things you say. I don’t. I think you want to believe them because you’re quitting.”

I love how Fincher in Se7en (1995) enhances its themes through his visual storytelling choices. Se7en’s dark color palette effortlessly fuses with the thematic darkness. Moreover, the grisly crime scenes are designed not just to shock but to have us question our own reactions. The film expertly toys with the audience by flirting with the show, don’t tell technique. You’re not shown all the details about the bodies, but you’re shown enough.

We don’t see John Doe commit a single murder, which only adds to the element of mystery and power of his character. You know what is in the box, but they don’t show you. You create the mental images of each murder, and in fact, these imagined images are far worse and more horrifying than anything the movie could have shown you. Se7en plays around with the knowing-not-knowing theme, spinning more terror from what we don’t fully understand.

Serial killers have long been popular in the entertainment media. The movie uses the motivations of the killer to create an intriguing story, playing around with it to create a gripping plot. This clearly makes John Doe one of the greatest villains in film history. But it also makes Doe point out that his actions “are going to be puzzled over and studied,” commenting on the dangers of giving killers a cult status, which also allows us to detach ourselves from them, thinking we could never do that.

Related Read to Se7en (1995): The 10 Best Movies of Brad Pitt

Se7en (1995) was Fincher’s second movie after Alien 3. While he went on to make masterpieces like Zodiac, The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo, Gone Girl, and Mindhunter, where each deals with a twisted and complicated character, none of his other works is darker than Se7en. While most of Fincher’s films are classics, this one definitely stands out, as it allows us to come face to face with familiar everyday bleakness, leaving us with the knowledge that indifference is not a solution and that the best we can do is stick around and fight.

Somerset’s quote, “Ernest Hemingway once wrote ‘The world is a fine place and worth fighting for.’ I agree with the second part.” sums up this emotion well. The idea here is that we need to recognize that there is a problem and that a solution can be worked on if we choose not to adopt an indifferent attitude toward it.

![Ad Astra [2019] Review – An Exhilarating cinematic Experience](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Ad-Astra-768x512.jpg)