Guillermo del Toro’s “Frankenstein” (2025) reimagines Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel through a prism of 19th-century aesthetics, religious imagery, and deep human melancholy. Mary Shelley, writing “Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus” at age nineteen, captured the unease of an age enthralled by scientific progress yet terrified of its consequences.

The novel’s combination of gothic horror and romantic philosophy challenged early 19th-century conventions, earning fascination and censure alike. Over two centuries, its reception has shapeshifted; from moral parable, scientific prophecy to existential lament. Shelley’s brilliance lay in granting the creature not only life but voice. Del Toro honors this by placing the creature’s consciousness at the center of the film’s emotional map.

This adaptation bridges del Toro’s fascination with monsters as metaphors with Shelley’s existential fight on creation, loneliness, and guilt. Visually grand and emotionally raw, the film transforms Shelley’s fable of hubris into a melodrama on the unbearable weight of not being seen.

Guillermo del Toro’s filmography consistently explores the intersection where myth and mortality meet, using fantastical narratives to illuminate the deepest truths about life and death. In “Pan’s Labyrinth,” del Toro surrounds his young protagonist, Ofelia, with a world of ancient creatures and magical trials, but this realm is always shadowed by the grim realities of war and mortality.

“The Shape of Water” reimagines a classic monster myth as a story where the boundaries between life and death blur. The director uses the supernatural to reflect on human vulnerability and the capacity for transcendence in the face of mortality. His films persistently linger at this rich crossroads of legend and existential truth.

Read: Here’s Why the Ending of The Shape of Water Doesn’t Work

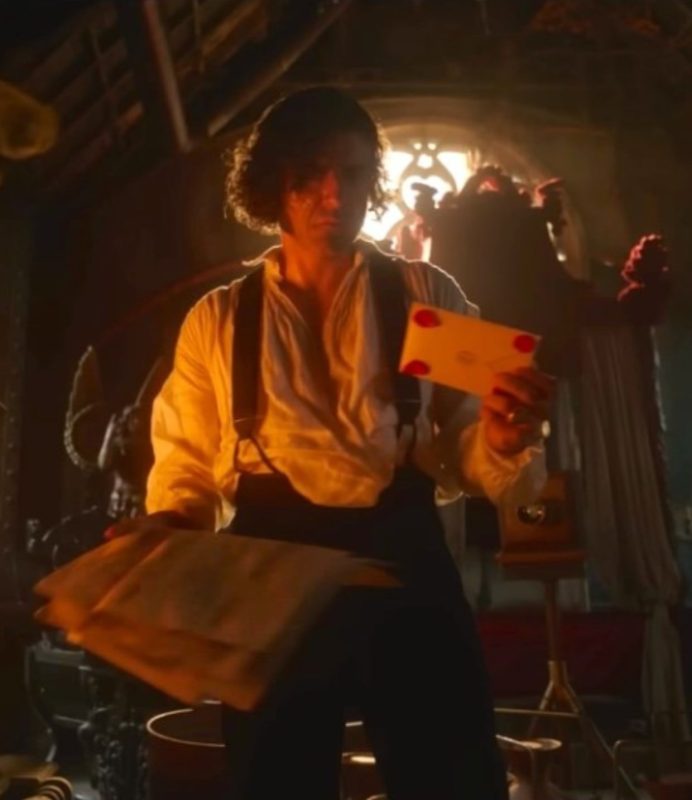

“Frankenstein” (2025) reinterpretes the story of the creature from the 1800s in a world poised between enlightenment, reason, and romantic rebellion. The sets brim with artistic references: neoclassical symmetry confronting Gothic excess; candlelight halos that evoke Caravaggio’s tenebrism. The influence of the Baroque appears in grand, contorted movement, each frame a tableau of spiritual, almost theatrical drama. Moreover, the dialogues throb with poetic intensity, their cadences echoing the verse of Goethe or Byron.

The camera in the film works like a sculptor’s chisel: carving figures in chiaroscuro, composing frames that recall baroque altarpieces. A homage to classical art becomes the visual and spiritual backbone of the film. In “Frankenstein,” visual empathy is magnified. The film’s palette here is colder than usual; icy grey-blue light is contrasted by warm candlelit interiors, representing a perfect see-saw of the emotions in each of the characters. The romanticism of design persists in every choreographed scene, every fog-drenched graveyard, every trembling close-up of a wounded hand.

This aesthetic interplay is influenced by Galant charm enmeshed in Gothic horror. The film’s design represents beauty as the mask for decay. “Frankenstein” transforms painting into performance, evoking classic artworks to deepen the narrative’s mythic register.

“The Sea of Ice” by Caspar David Friedrich: the film opens and closes in the Arctic with a ship trapped in ice, its timbers groaning as the crew struggles to hack a path through the frozen sea, directly recalling Friedrich’s imagery of a vessel immobilized and crushed by frozen slabs. Victor and the Creature are like that wrecked ship, each has tried to defy natural and moral limits, only to find themself immobilized in a void where ambition, vengeance, and desire are ground down by nature’s law that offers no rescue.

“The Creation of Adam” by Michelangelo: When the creature and Elizabeth meet for the first time, del Toro stages the moment as a resurrection of Michelangelo’s fresco. The camera lingers on their outstretched hands, the sparse air pulsing between touch and transcendence. Michelangelo’s painting depicts the divine spark, Adam receiving life from God. In the film, that gesture is reversed. Elizabeth, mortal and fragile, extends her hand toward the outcast creation.

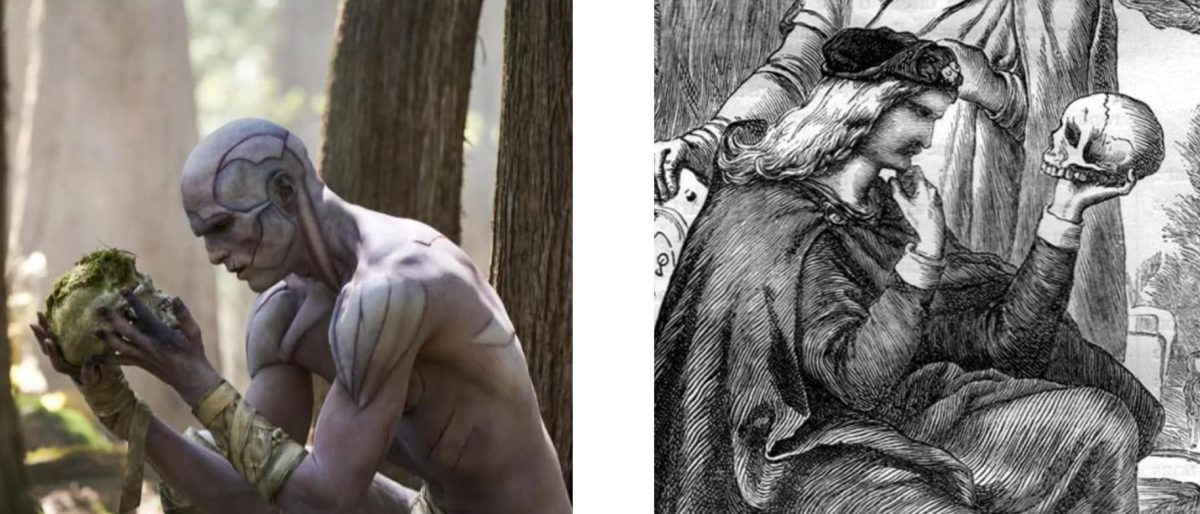

“Hamlet and Yorick’s Skull”: When the creature first ventures out of the laboratory, he discovers a pile of skeletons in the forest, and del Toro directly references the depiction of Hamlet holding Yorick’s skull. The creature gazes into a skull’s hollow eyes, contemplating mortality. The monster confronts the absence of a soul.

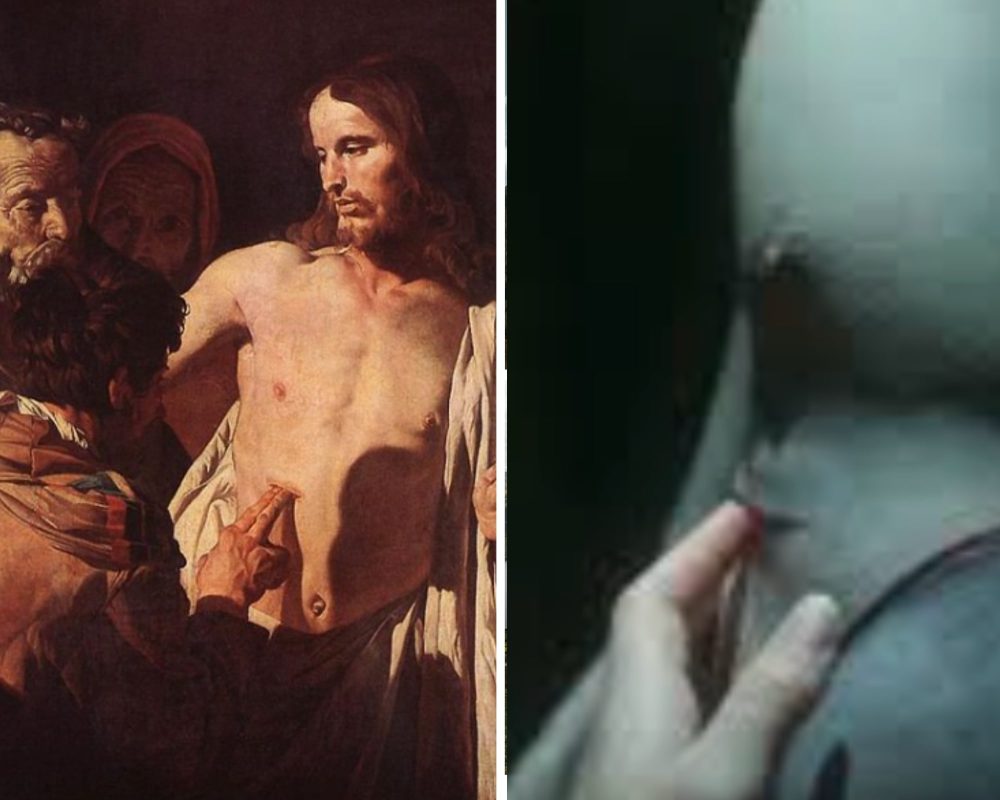

“The Incredulity of Saint Thomas” by Gerard van Honthorst: In another pivotal scene, Elizabeth touches the creature’s wounds, her fingers trembling over his stitched flesh. The composition mirrors St. Thomas probing Christ’s wounds, seeking proof. Here, Elizabeth’s gesture is an act of understanding. Her empathy replaces belief, suggesting that faith can bridge what science divides.

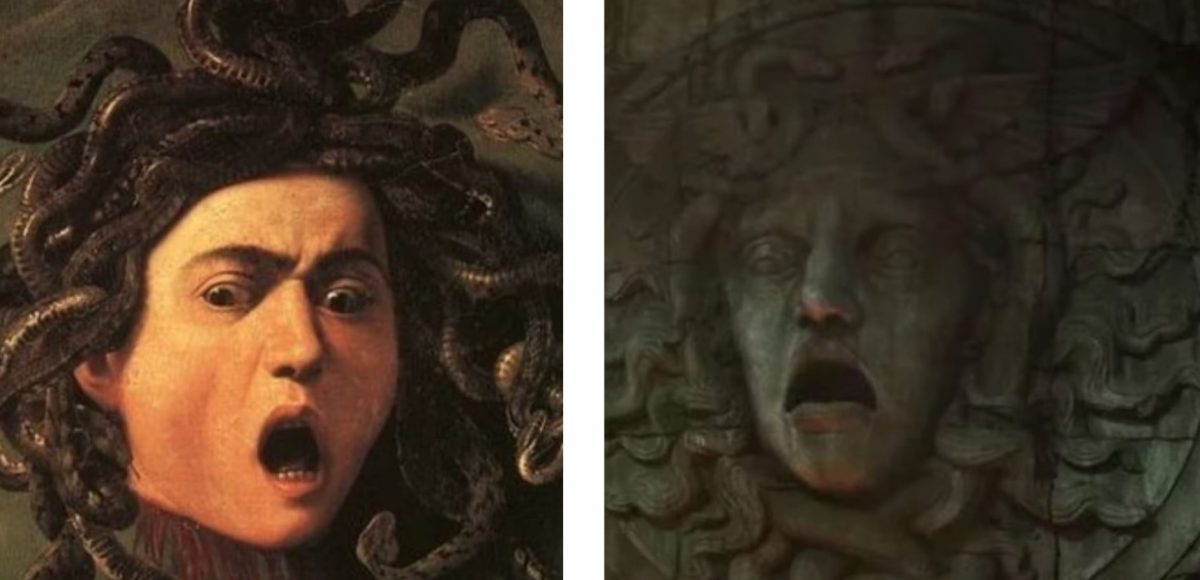

“The Medusa Sculpture”: The recurring image of Medusa punctuates the film; etched on mirrors, carved into doors, glimpsed in the creature’s nightmares. Medusa here symbolizes transformation through terror. She could also be placed as a metaphor for the monster’s gaze: whoever looks upon him confronts their own petrifying fear of difference.

Also Read: Stitched Souls: Identity and Emotion in Guillermo del Toro’s ‘Frankenstein’ (2025)

Baroque architecture fills the screen, echoing Victor’s spiral into obsession. Neoclassical statues haunt his study, the cold marble bodies mocking his attempts to animate dead flesh. Every scene in the film bears the tension between artistry and entropy. The film’s romanticism is not decorative but ideological. Candlelit banquets exude morbidity; each gesture is choreographed as improvised theater. This melodramatic texture recalls the operatic rhythms of early Gothic novels that are passionate, overwrought, yet sincere. The design of the scenes in “Frankenstein” shows that excess, in romantic art, is simply honesty under pressure.

The concept of the Galant style, which prized conversational lyricism in the 18th century, finds a true cinematic embodiment in the film’s language. Characters speak as if composing ephemeral sonatas; airy yet aching. The film’s dialogue often slips into poetry, every exchange saturated with yearning and despair. These linguistic flourishes are not an ornament but an essence. Some of the dialogues truly do reveal the emotional architecture of the film:

When the creature whispers, “I called your name and understood I was alone,” the line captures the shock of creation without consent. The creature’s existence becomes a cosmic orphanhood, calling for his maker mirrors humanity’s call to a God. The silence that follows is unbearably hurtful, and an empathy for the creature being abandoned sets in. During a confrontation, the creature cries to Victor, “I am obscene to you, but to myself I simply am.” This declaration challenges the boundaries between the maker and the made. The creature’s self-recognition is an attempt at survival. His hurt mirrors every child rejected by a parent’s ideals.

Elizabeth’s compassion for the creature reaches beyond gender, species, or social norms; it is beyond life itself. Through her, the creature experiences the tenderness Victor denied him. Elizabeth’s dying words to the creature were “To be lost and to be found, that is the lifespan of love”. These lines serve as a benediction to the creature. Their relationship, more spiritual than romantic, reframes the Gothic trope: it is not the reanimation of the dead that is terrifying but the resurrection of feeling that is.

At his deathbed, Victor’s final words bind the creator and his creation. We realise, despite their fight, they share the same despair: to exist without solace. “While you are alive, what recourse do you have but to live?” These words come from Victor as an exhausted confession. Their parting is a recognition that loneliness binds them closer than kinship ever could. In the climactic reconciliation, the creature says, “Perhaps now, we can both be human.” The line softens the centuries-old boundary between monstrous and man. Forgiveness becomes the film’s true resurrection.

The final image of Frankenstein remains etched in silence. The creature, once terrified of daylight, walks toward the sun; its warmth no longer a threat but an invitation. That slow ascent completes the existential arc: the monster seeking not revenge but reconciliation with the world. The film ends with a quote by Lord Byron, “the heart will break and yet brokenly live on.”

The creature was left with the biggest human adventure to experience, to search for connection and love. “Frankenstein” (2025) is not just the usual cinematic adaptation; it is a dialogue between mediums: novel, painting, myth, cinema, life, and art. It stands as both homage and evolution. Eventually, it’s a romanticized gothic dream that turns monstrosity into humanity’s most ancient mirror.

![Castro [2009]: A Hilariously Absurd Existential Comedy](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Castro-1-1-768x429.jpeg)

![The Family Game [1983] Review – An Incredible Dark Comedy on the Middle-Class Nuclear Family Life](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/The-Family-Game-1983-768x432.jpg)