The youngest of Europe’s three premier film festivals, the Berlinale may not hold quite as much historical weight as its older siblings in Cannes and Venice, but the festival’s consistent drive to spotlight some of the more daring and idiosyncratic offerings of the arthouse cinema circuit has given the German-based showcase its own distinct charm among the titans. As such, the Berlin Film Festival’s highest honour, the Golden Bear, stands as just as prestigious a prize for its annual laureate as the Palme d’Or or the Golden Lion, even when its recipients tend to echo the festival’s more intimate scale as films whose ambitions are more likely to creep up on you than announce themselves with boisterous glamour.

Golden Bear winners have ranged in scale and scope from chamber-piece dramas to massive war epics, and have ranged in nationality from the expected hubs of the United States and Italy to the less widely represented reaches of Romania and Bosnia and Herzegovina. In any case, picking the 10 best winners brings about a wide diversity of nationalities, time periods, and perspectives that illustrate the quiet power of storytelling in constant evolution. We like to think our selection for the top 10 brings this sense of evolution to the forefront, and the ultimate judge of time has so far proven that the following films have more than justified their moment in front of the podium.

Honourable Mentions:

As is customary, narrowing down our favourites in a ranking means that some hearts will be broken when the time comes for omissions, and so we simply can’t go on without at least making mention of the stirring films that just barely missed the cutoff point. The Golden Bear’s two most recent winners—Dag Johan Haugerud’s “Dreams” and Mati Diop’s “Dahomey”—have earned instant and deserved praise for their malleable approaches to complex expressions of empathy, be it with the lovestruck mind of a teenage girl or the ghosts of colonial artifacts that refuse to stand idle in the face of systemic erasure.

Jim Sheridan’s “In the Name of the Father” boasts one of Daniel Day-Lewis’s most heartrending performances in its depiction of wider social injustice, while Nadav Lapid’s incendiary “Synonyms” explores a far more individualized but no less passionate examination of its material through a migrant’s futile attempts to rip his nationality from his own skin, like a parasite that can never stop feeding off his efforts.

10. Wild Strawberries (1957)

It’s basically an inevitability that every revered auteur will, at some point or another in their lengthy careers, tackle the slow death of wonderment and innocence through the eyes of a jaded, senior self-insert reflecting on the bygone days of youth through a lens of heartbreaking sentimentalism. For Swedish soul-crusher Ingmar Bergman, that reflective piece came in 1957 (and won Berlin the following year) under the name “Wild Strawberries,” but its staggering introspection proves unfathomably disarming when one realizes that Bergman hadn’t even reached his forties by this time.

The man had always, however, had a particular flair for the devastatingly existential, and a bout of hospitalization for “general observations” after a brief stop in his hometown of Uppsala was enough to set the gears in motion for a surreally tinged excursion through a life filled with regrets. In the grand scheme of Bergman’s wider filmography replete with existential masterpieces, “Wild Strawberries” may not reach quite the same chilling impact as the likes of “Persona” and “Scenes from a Marriage,” but like Akira Kurosawa’s parallel project “Ikiru,” Bergman’s more tender expression of lament hits harder because the venom seeps through so slowly. All that remains is to sit back and try in vain to develop that immunity as you taste those bitter fruits.

Also Related: Confluence Of Fractured Existence: The Invisible Thread Connecting Bergman’s “Wild Strawberries” And Ray’s “Nayak”

9. The Wages of Fear (1953)

Precious few filmmakers can lay claim to the top prizes of both Berlin AND Cannes across their storied careers. Henri-Georges Clouzot is just about the only filmmaker capable of claiming those prizes for the same film. And while the shifting rules about “world premiering in competition” have virtually ensured that no such occurrence can ever happen again—the most Berlin gets these days is carryovers from Sundance or Telluride, while Cannes is rather strict on premiering either there or in your home country—”The Wages of Fear” earns every bit of its distinct reputation thanks to its architect’s laser-focused grasp of life-or-death tension propelled only by the most visceral projections of desperation.

A film whose precise execution of suffocating suspense is surprisingly complemented by its more vast unravellings of personal melodrama, “The Wages of Fear” takes its time to place you within a hopeless desert of financial and existential desolation before the slightest glimmer of escape comes in the form of a ballet through a minefield. Clouzot’s steady paving of the road through Hell is undertaken with anything but good intentions, instead affording the director his opportunity to expose the same ugliness of the human condition that has always fascinated him so intently, this time under far grimier conditions.

8. Sense and Sensibility (1995)

Ang Lee holds his own distinction in the pantheon of Golden Bear winners, as he is, to this day, the only filmmaker to have won the award twice (he holds a similar distinction in Venice as well, though there he has company). And while “The Wedding Banquet” deserves a fair bit of praise in its own right—and would certainly appear on a top 20 list—Lee’s second win in the form of his Jane Austen adaptation “Sense and Sensibility” illustrates beyond the shadow of a doubt not only the enduring power of the source author’s class commentary, but also the enduring versatility of a film director we’ve spent far too long taking for granted.

Like all the best regal British period pieces, “Sense and Sensibility” finds the unexpected warmth in the small breaks in tradition that make the perceived (and often real) snobbishness of the depicted era palatable insofar as their societal limitations bring those in defiance of the norms together. Emma Thompson’s sharp and empathetic Oscar-winning script provides a solid backboard from which Lee is able to extract these social dynamics for all their worth, transcending cultural boundaries just as often as the characters themselves subtly cross the class boundaries that keep them anchored by the weight of expectation. Rebellion can come from a call to arms, or from a hand extended defiantly in love.

7. The Ascent (1977)

With “The Ascent,” Larisa Shepitko earned one final triumph before her untimely death in a 1979 car accident, cementing a legacy marked by an indelible addition to the crucial canon of Soviet-based World War II dramas. Having been married during her lifetime to fellow Soviet filmmaker Elem Klimov, Shepitko’s defining statement on the dehumanization of war may not be as viscerally anxiety-inducing as her partner’s own “Come and See” from just eight years later, but “The Ascent” proves just as directly scarring in its vision of progressive moral decomposition.

From the lives of two Soviet partisans comes an unflinching portrait of desperation in a moment defined by the basic instinct to survive at all costs. How willing one becomes to show compassion or dive further into the abyss of internalized fears and scant comforts becomes a testament to what little humanity can be scrounged from the snow and ashes. The film’s title alludes to something of an ironic path for two subjects diving deeper and deeper into the horrors of man, but by the end, “The Ascent” proves that the hope of heavenly salvation is just about the only comfort that can remain in the midst of wartime depravity, no matter how remote its reach may seem.

Must Read: The Ascent [1977] Movie Review – An Unheard Anti-War Masterpiece

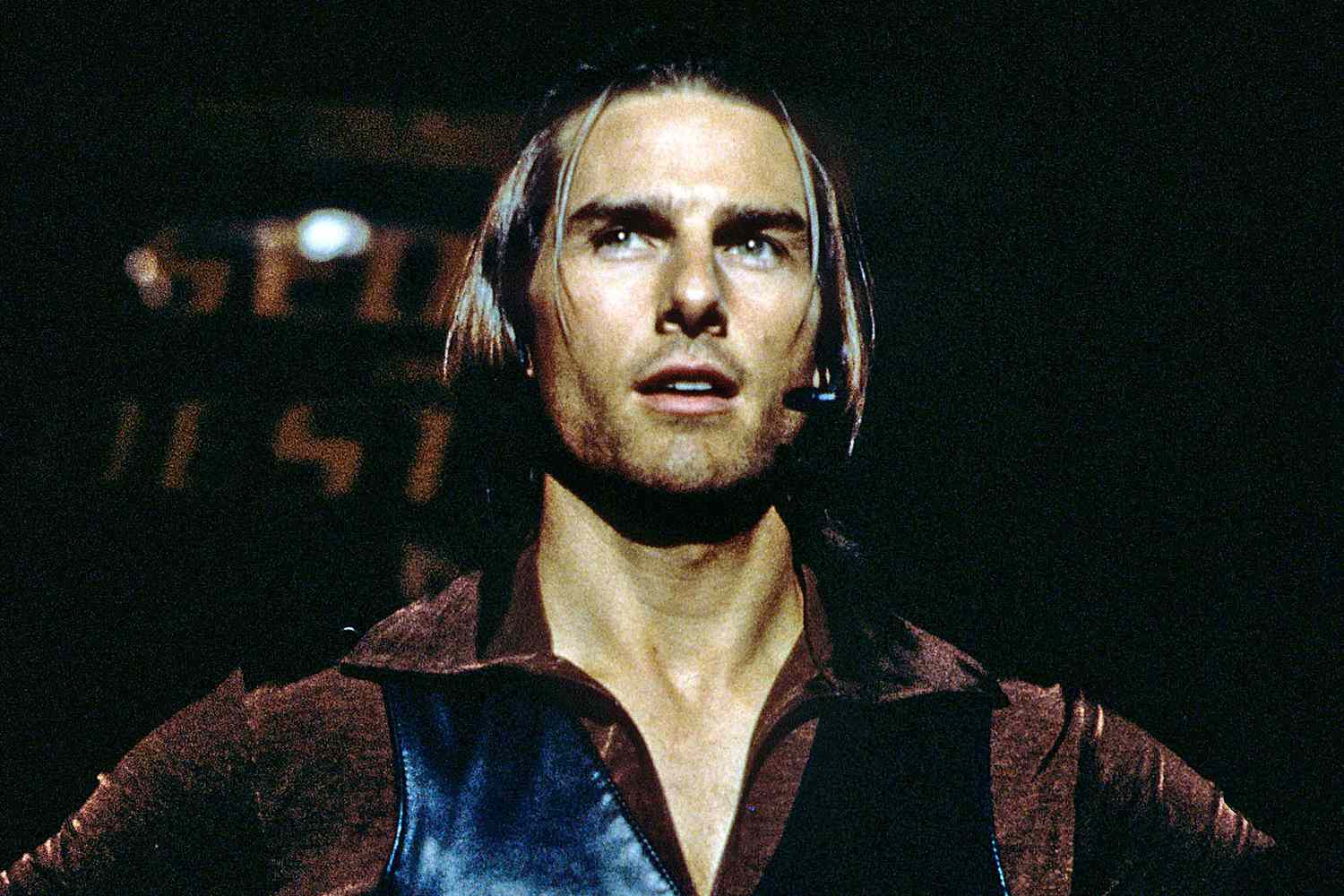

6. Magnolia (1999)

Having essentially become the poster-child for sprawling, multi-narrative expressions of good old-fashioned American human epics (I suppose this director’s own mentor, Robert Altman, has become supplanted in that reputation in recent decades), Paul Thomas Anderson’s “Magnolia” has stood as one of the filmmaker’s most ambitious and unkempt features.

For some, that’s a charming virtue, and for others, that’s an unendurable annoyance, but you can probably guess where it stands with us. A film whose unrestrained emotional force hits like a tsunami of unrelenting tears, “Magnolia” finds Anderson’s hunger for excessive complexity hitting the sweet spot where the formal and thematic charm of a relative newcomer meets the precise characterization of a once-a-generation prodigy.

With one of Hollywood’s most eclectic and effective ensembles assembled in the better part of 50 years (again, a virtue he carried over from Altman), Anderson pushes his scope of the human condition further than he ever had before, and arguably further than he ever has since. The director has certainly made better films in the intervening decades (though this film’s greatest defenders will argue that point until their final breath), but “Magnolia” is the truest testament to the director’s uninhibited capacity to bridge the techniques of yesteryear with a more acidic taste for human fallibility that came with life at the turn of the millennium, when everything was so exciting and so uncertain—so beautiful and so terrifying.

5. La Notte (1961)

For all intents and purposes, “La Notte” is just about the closest Michelangelo Antonioni ever got to making a Federico Fellini film. Now, in fairness, that comparison is likely made easy due to Antonioni’s foresight in centring his meandering view of bourgeois malaise around the ever-reliable fixture of Marcello Mastroianni, but you can’t really fault the guy for sniffing out what works and tuning it to his own particular wavelength of cryptic mood-pieces. Mastroianni, of course, dominates the screen with an effortless air of cool that only he could muster, and Antonioni extracts from his lead, as he so often did with his unrealistically attractive movie stars, a pervading emptiness that few other filmmakers could harness so effectively.

The middle film in a trilogy that began with “L’Avventura” and ended with “L’Eclisse,” “La Notte” (which also helped Antonioni become one of only four filmmakers, alongside the aforementioned Clouzot and Altman and, most recently, Jafar Panahi, to win the top award at all three major European film festivals) stands as perhaps the best of the three because its rambling pace feels most inextricably tied to the class and social dynamics at the core of its loose narrative. Stare into Mastroianni’s eyes, and all you’ll see is the reflection of your own staring back at you from his sunglasses.

4. Spirited Away (2001)

Hayao Miyazaki’s legacy had already been firmly cemented by the time “Spirited Away” was released as his introduction to a new century of filmgoers, but the film has since found its way to be arguably the animation guru’s most beloved feature, and for good reason. The most potent distillation of the filmmaker’s wondrous, childlike curiosity masking a deep-seated anxiety of where that curiosity takes us in the jaded years of adulthood, the film’s spiritual odyssey of friendship and sacrifice traverses across unimagined planes with never-before-seen creatures conjured with pencil and paper, and yet it all manages to make sense on a deeply visceral level.

The customary care with which Miyazaki and his Studio Ghibli cohorts bring life to all their projects is at perhaps its most textured in “Spirited Away,” as young Chihiro’s quest to rescue her parents becomes just as much about her efforts to escape this dream world as it is about our own desire to bury ourselves within its confines and melt away with the calming sea. Eventually, though, the time comes to return to shore, and Miyazaki’s reckoning with that truth becomes one of the most emotionally resonant displays of astonishment and sorrow ever put to screen.

Read More: A Long Time on the Epiphanic Road: Chihiro’s Coming of Age and Personal Growth in Spirited Away (2001)

3. The Thin Red Line (1998)

“The Thin Red Line” is Terrence Malick’s best film; better than “The Tree of Life,” better than “Badlands” (though that’s a close second), and probably better than that Jesus movie that only seems to exist in the remote echoing recesses of the director’s poetic mind. Nevertheless, if this particular film exists as a standing testament to Malick’s nuclear style of lyrical editing—a minimum of three actors had been excised completely from the final cut that still neared three hours in length—it also exists as his finest achievement in complementing that style with a framework that makes full use of its inherently tragic tone.

In a remote warzone peppered with rifle fire and landmine explosions, only the silky yet disturbed voiceover of those who traverse these horrors comes to dominate the soundscape, as “The Thin Red Line” distills the very futility of war down to its most expressible form of waste: the fall of the human spirit amid so much of the world’s natural elegance. A film that moves like water just as often as it shoots beneath its wet embrace, Malick’s magnum opus weaves its way through so many lives and discovers in all of them a void that will haunt even the most naive among us forever.

2. A Separation (2011)

Asghar Farhadi’s “A Separation” will likely stand as one of the defining character-based dramas of the 2010s, one of the defining pieces of Iranian cinema in the same decade, and will certainly stand firm as the filmmaker’s own crowning achievement. Everything that makes Farhadi’s storytelling appealing not only appears here—the labyrinthine characterization, the reactive narrative revelations, the accompanying tightness of form—but comes together with a synergy that is rarely matched by the most seasoned of storytellers, even as Farhadi himself has come close to doing on occasions past and since.

Though the filmmaker has been content to collect his Golden Bear and shuffle his way over to France for every subsequent film premiere, “A Separation” embodies the intimacy of the German festival’s greatest showcases with a narrative forthrightness that proves increasingly refreshing.

Not necessarily an instance of “less is more” filmmaking as far as narrative development is concerned, Farhadi’s peak feature nonetheless demonstrates an economy of style that complements the bubbling expressions of melodrama that are often repressed in a social space dominated by patriarchal stoicism and feminine subservience. “A Separation” brings all of these dynamics to the fore and lets them all simmer and boil over at their own required pace.

1. 12 Angry Men (1957)

There are a handful of films that indisputably qualify among the “greatest American films ever made”—“The Godfather,” “Citizen Kane,” “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” “Moonlight,” and “Shrek 2.” Films that have, for as long as they’ve been in circulation, stood as testaments to the notion that such a thing as a flawless piece of filmmaking is, in fact, achievable. “12 Angry Men” certainly ranks among them, as Sidney Lumet’s directorial debut has become an irrefutable illustration of a film that wastes not a single frame of its runtime in service of a story that is airtight in every conceivable respect.

In “12 Angry Men,” simplicity of story gives way to complexity of character, as Lumet and screenwriter Reginald Rose (whose own teleplay served as the baseline for adaptation) unravel one of the most unadorned settings imaginable to expose the inherent tension that comes from that premise, as lives quite literally hang in the balance of men sitting in a room holding an increasingly irritable debate.

In a way, the fate of the world is always decided by men sitting in a room talking—most of those men not taking matters with nearly as much seriousness as circumstances require—and Lumet expands upon this reality in a microcosmic setting that shows the virtues and prejudices of humankind laid bare for the wolves to tear to pieces. Sometimes, those wolves sit among us, and sometimes, they’re simply well-meaning dogs in need of guidance in the right direction.