Actress-turned-director Natalya Kudryashova’s sophomore feature, Gerda (2021) is set in the turbulent, harsh social reality of contemporary Russia. However, the filmmaker studies her characters and their painful existence in a manner that carries metaphysical resonance and is devoid of a social-realist approach. In fact, exploration of metaphysical space in Russian cinema has bestowed us with unique works. From Andrei Tarkovsky, Alexander Sokurov to Andrey Zvyagintsev, we have witnessed mysterious tales of spiritual catastrophe and loaded with grand metaphysical implications. Natalya’s Gerda doesn’t withhold the hypnotic power of those aforementioned filmmakers. Yet she takes a step in that direction, offering a portrait of a young woman trying to embrace the spiritual aura while getting clobbered by the ubiquitous social cruelty.

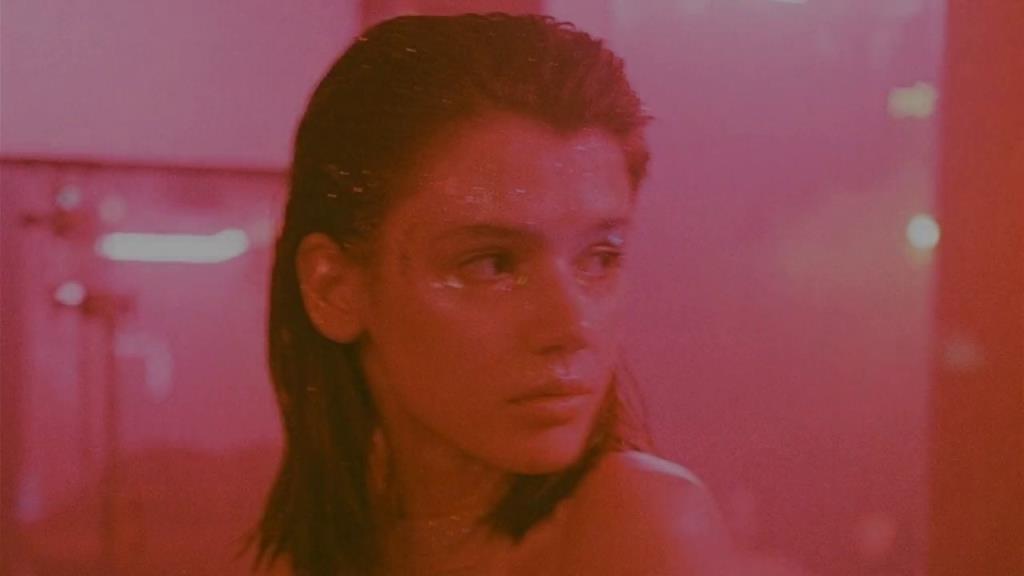

The metaphysical intent of writer/director Natalya is evident in the title, Gerda – a central character in Snow Queen. The film opens with a woman trying to flee her suffocating reality. She is being transported somewhere. She asks the car to stop, leaves her kid in the backseat, and goes out to the woods to pee. But suddenly she starts running as if a paradise is waiting on the other side of the woods. The prologue cuts to a strip club, and our Gerda isn’t singing about roses that adorn her window box garden but offers private dance to a man. Later, she is humiliated by her colleagues for ‘going further’ with the man for money. The jolt the filmmaker provides by unexpectedly initiating us into Gerda’s world of naked bodies and preying eyes is unnerving.

Related to Gerda: Nine Days [2020] Review – A tender and metaphysical tale about the human condition

Gerda’s real name is Lera (Anastasiya Krasovskaya), a student of Sociology. She lives with her depressed, sleep-walking mother in a somber apartment complex. Her father is largely absent, who occasionally barges in late-night, is drunk, and behaves violently. Forced to be the family-head at a very young age, Lera doesn’t have many options apart from dancing at a strip club. Her body satiates the voyeuristic pleasures of male customers, whereas her aloofness is interpreted as arrogance and draws vitriolic comments from her female colleagues. The women, however, aren’t simply portrayed as bullies but what they say to Lera aka Gerda is part of their strange coping mechanism. In fact, at one touching moment, the women jump in and help our protagonist.

Natalya throws in these hard details to makes us wonder about Lera’s soul that dreams of a better life and attempts to shield others from their pain. The treatment of this core subject matter does falter at times due to symbolic overtones or emotional detachment, which nonetheless reverberates with exquisite imagery. The question of ‘soul’ is raised earlier in the narrative when a world-weary Lera listens to the class that touches upon Plato’s theory of the soul. Whenever she goes to sleep, Lera finds herself (the soul) floating in a dense forest. The soul’s desire to escape to the metaphysical space is expressed through the recurring dream. At the same time, in reality, her pure soul at one moment thwarts the menace of carnal hunger.

In one of Gerda’s tense sequences, Lera is surrounded by two naked men in a hotel room. She accompanies her stoned friend, who agrees to provide ‘private service’ to the wealthy and drunk men. Lera is simply there to keep an eye on her. But when the friend passes out, the men casually strip down and consider her the substitute. What Lera does at that moment is simply astounding and transcends the atmosphere in the room. However, Lera often finds losing herself amidst the wider societal malaise. The sociology students before finishing their graduation are given the task to conduct a survey, i.e., visiting people door-to-door and interviewing them to fill up a form.

Also Read: Courier (1986) Review – A Poignant Coming-of-Age Drama Set in the Twilight of Soviet Union

From an old woman who barely survives on her pension to an old gentleman hoarder living with yowling cats and a lonely kid wishing for chocolate, Lera finds a greater discrepancy between the bleak reality and the absurd questions conceived for the survey. Natalya’s Gerda could be criticized for stacking the narrative with certain layers and characters to exhaustively disperse the gloominess. For instance, I was frustrated by the dynamics between Lera and her only friend Oleg (Yuriy Borisov), an artist working as a gravedigger.

In fact, apart from Lera, the other characters are less explored and they more or less remain as a shade in Natalya’s canvas of brutal society. A mother believing in miracles, a father lost to alcoholism, a friend who talks about his ‘customers’ buried in coffins, the characters after a point only remain as an essential part of the narrative’s feel-bad aspects.

Nevertheless, the redeeming aspects of Gerda are the remarkable performance by Anastasiya and the moody imagery which evokes the perceived spiritual degradation of contemporary society. Overall, Gerda (111 minutes) is a distressing character portrait of a young woman, navigating the soul-crushing quandaries of the modern world.

![Dragonfly Eyes [2017]: Locarno International Film Festival Review](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/dragonfly_eyes-h_2017-768x433.jpg)

![The Platform (El hoyo) [2020] Netflix Review – A Fiendishly Entertaining Allegory on Social Inequality](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/The-Platform-2020-768x512.jpg)