Discussing Systemic Sabotage and Institutional Suicide in Jana Gana Mana (2022): The latter half of the popularly canonized ‘New Generation’ Malayalam cinema has witnessed a more radical identity to the content it propagates following a radicalization of the medium itself in the early 2010s. While an argument can be made against this citing that the politics of some of these films are more reactionary than revolutionary, one cannot dismiss an obvious attempt at the intended political subversiveness these productions strive for and how formally innovative they have become.

For example, recent films like Nayattu (2021) and Salute (2022), while indifferent to critical acclaim, have both attempted in exposing the double standards of the state machinery by contextualizing the corruption within the institutional body of law enforcement, the police. These narratives no longer show the extremely intelligent machismo male lead who strives for justice and brings down tumors of society with a strong sense of right and wrong. Rather, they show individuals conflicted in their actions, without any concrete sense of right or wrong, helplessness at being mere pawns waiting to be scapegoated by the modern feudal lords. It is amidst this canonization of cinema which depicts the depletion of trust, in judicial and law enforcing institutions, that director Dijo Jose Antony and writer Sharis Mohammed bring the bold albeit conflicted Jana Gana Mana (2022).

Similar to Jana Gana Mana (2022): The Portrayal of the Subaltern in Sachy’s Ayyappanum Koshiyum (2020)

The question of whether Jana Gana Mana (hereby addressed as JGM) is a good film worth your while is pointless. It is a definite film. It tries to be omnipotent in its depiction of the vice and rot of contemporary Indian society by presenting the failure of an interconnected system and the resulting aftermath. Antony continues his use of the courtroom, following his use of the same in his debut film Queen (2018), as his stage to question the aforementioned vice and further expose underlying infringements within the institutions of law, education, law enforcement, and the superficial propagators of truth; the media. This essay analyses the so-called ‘institutional killings’ these entities are responsible for as a result of biases and preconceptions within the narrative of JGM and further explores the unique structure the creators have used in convincing audiences of their prejudices.

The film is quick to establish a particular saffron-clad community as the obvious evil. It shows sequences of the unrest and violence this group is responsible for but does not linger on emphasizing more than necessary as who they are alluded to in the real world is evident through the mimicking of real-world events in the film. However, the film refrains from siding with any oppositional forces or affiliating itself with any particular ideology thus taking a liberal stance in an attempt to tame two extremist outlooks. It does this through a sequence of real-life events (such as the Hyderabad gang rape and encounter killing of 2019, Rohit Vemula suicide of 2016, The killing of an Adivasi man, Madhu of 2018, etc) adapted onto the silver screen and narrativized in a manner that joins them together in pushing for an ulterior narrative against reactionary woke politics.

Perhaps the most important cite of institutional suicide within the film is that of the media. Is the media the reporter of truth or creator of truth? The film is of two independent halves. The first half reads like a newspaper report on an inciting incident, the following reactionary upheaval and ultimate verdict. However, the second half becomes a reality check for the many prejudices the common mass subconsciously holds close to their chest. Similar to how Saba’s death is used by the residing Home Minister, Nageshwara Rao, to bolster his election campaign by swaying popular opinion through media manipulation, Antony attempts to convince his audience that their sense of relief and jubilation at witnessing the encounter killing is validated by showing characters on-screen reacting positively to the killing. This is furthered by having the protagonist (till that point), Sajjan Kumar (Suraj Venjaramudu), carry out the killing himself. Through this, Antony frames the audience and apprehends them for their perceived discrimination at celebrating the extrajudicial killing of suspects without trial.

The film shows how the media not only incites a false narrative but goes out of its way to propagate and conform to it to make it seem like the celebration of the encounter killing was organically generated among the masses rather than the masses being manipulated into thinking it was a call for celebration. The very fact that Saba’s ‘rape’ was reported with huge headlines over multiple other rape cases across the country raises questions about why one particular case was sensationalized. The film suggests that there is particular politics in having such scoops being ingrained into the minds of the general public; that this is the news of the hour and not hundreds of other lynchings, deaths due to hunger, or fraudulent activities of the government being reported. So beyond the discourse of the media being the reporters or creators of truth, it becomes an institution of weighing truth and deciding which truth matters over the other. “There is only one truth and that truth will win” goes the opening monologue of JGM. But when the institution responsible for exposing that truth does so with the ulterior motive of choosing sensational scoops for commerciality and click counts, it commits suicide in its action of deciding which truth matters.

The obvious site of corrupt power being exercised in the country is within the police department. In JGM as well, a peaceful (nonetheless vocal) protest by Gauri and her colleagues on taking action against the perpetrators who murdered their lecturer is met with oppression and them being labeled ‘anti-nationalists’ by the popular media. It parallels the gruesome violence that happened at Jamia Millia Islamia in 2019 and the attack at Jawaharlal Nehru University in 2020, both cases in which either the police incited the violence and were part of it or did nothing to prevent the agitation. Amidst the chaos, Sajjan Kumar is introduced as an empathetic ACP to negotiate with the students at the University and investigate the murder of Saba. When warned by a colleague of the unrest caused by students, he responds “They are students right? Not the Taliban”. Phrases such as this persuade audiences to immediately identify Kumar as the just figure of hope. Even as mistrust ensues between him and the students of the Central University of Ramanagara, he eventually wins them over with the encounter killing of the suspected 4.

However, not only is Kumar eventually revealed to be a puppet in the government machinery but ultimately the brainchild of the whole scheme. Thus reinforcing the fascist manipulative image often associated with the institution of law enforcement. The very body that exists for maintaining decorum creates havoc within an educational body, the same body in charge of assisting in providing justice to those at a loss of it confiscates that very same justice, and the body that assists the court in passing judgment takes judgments themselves and in addition hinder the functioning of the law altogether. Ultimately, the institution of law enforcement not only ceases to accurately perform its duty but also sabotages itself and the functioning of other government bodies.

Institutions of education are characterized to be bodies of discourse and discussion for ultimately arriving at sensible conclusions, providing solutions and entry points of research, and the growth of new minds who will one day become the future of the country. However, in JGM, the Central University of Ramanagara ends up becoming a traumatic battlefield of mindless violence and herd mentality. The police occupation of the University leads to the burning of books and destruction of libraries thereby showing oppression against any form of inculcated knowledge that may lead to dissent. It reminds one of the Nazi book burnings of 1933.

As mentioned before, students are senselessly labeled anti-nationalists for seeming to stand up for their lecturer who was a Muslim. It is in this very same institution that the Vice-Chancellor belittled the death of an employee citing the clothes she wore as a probable reason for what happened to her. Such ignorance for important pillars of education within the University itself shows the underlying neglect for both intellectual growth and sympathy for humankind thereof. Additionally, the film also depicts the misery faced by Divya, a student who seems to be from a lower class, as a senior Professor belittles her and denies the completion of her PhD, citing her appearance to not be worthy of an academic. He tells her that in order for her to know her worth, she should look at herself in the mirror citing her dark skin tone and further stating her role in society is to only sweep floors and clean garbage.

The Savarna mentality that has plagued the education system and the disregard it has for minority populations is evident through the examples of Saba and Divya. Parallel to this, a scene from Maharaja’s College in Kerala, a college historically known for being politically active, shows a college lecturer having to push his students to participate in political dissent and join in solidarity with the students of the Central University of Ramanagaram. This indicates how politics has unfortunately moved away from the physical realm to one that only exists in the digital one. When the cite of educational growth and intellectual stimulation becomes one of bloodshed and disruption of discourse, where the head of the institution and senior members of staff are facetious to issues of central concern and where the very revolutionary politics taught in theory are not produced in practice, there the institution fails to generate ambitious youth who are the future of the nation and is another example of self-sabotaging institutional suicide.

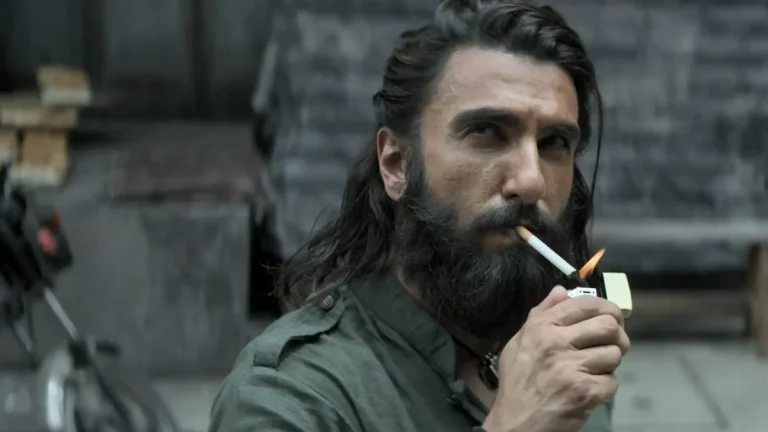

Finally, the institution depicted to be the most belittled is that of law. The encounter killings done in the film are done under the presumption that it would take years for the convicted to be tried in court and even if found guilty, will ultimately only “eat biryani in jail” with no form of ‘true justice’ being delivered. The film shows the media taking responsibility for investigating and identifying the wrongdoers while the police are shown to pass judgment and carry out the execution. Ultimately, the court becomes merely an institution of ‘clowns in black’ as Aravind Swaminathan (Prithviraj Sukumaran) puts it. Had the filmmakers not decided to base the second half as a courtroom drama, the law may have been completely avoided as seen in multiple mainstream template films.

However, even during these scenes, besides Swaminathan himself, everyone else including the opposing lawyer and the presiding lawyer, come across as unilaterally discriminatory, similar to you or I, in their outlooks towards the murdered convicts. Even the presiding judge claims the convicts look like people who’d be involved in the act of murder, thus reinforcing Swaminathan’s argument in the baseless prejudice that has seeped into society, even among its most educated members. Ultimately, the statement by Saba’s mother that ‘no law is greater than justice’ is called to question. Who decides who receives justice and in what form besides law itself?

While the film focuses on establishing the institutional fallacies that contemporary society is a victim of, it simultaneously tries to make evident that the problem is not merely a monolithic issue and that the common public has their own prejudices to partially blame for many regressive attitudes the film addresses. The general public is shown to quickly judge the suspected 4 as the obvious culprits without considering the possibility that they could have easily been framed by the police to satisfy the public outrage. The filmmakers seem to juxtapose this with how they previously questioned the integrity of the police when there was a delay in producing the suspects in court. Swaminathan’s argument in court that public sensibility against the suspects has largely been shaped by their physical appearance and the area the suspects come from unfortunately rings true not only within the domains of the film but in the real world as well.

Antony further liquidates the boundary between what is truth and not through the dichotomies of his central protagonists. As mentioned earlier, Kumar is intentionally presented as the ‘good cop’ in the beginning so that audiences resonate with a morally just individual who is in some position of power and is thereby capable of change. However, this is subverted in the second half. Similarly, while Swaminathan, being played by Prithviraj, automatically makes audiences feel he too could be a good guy, the initial trailer and teaser present him as someone who has committed treason and shows no remorse for it. Additionally, his initial interactions in court are characterized by a cynical approach to human emotions and are rather unsympathetic to the victim herself. This seems to be done to create polarities between Kumar and Swaminathan for the binaries of good and bad which is later subverted to add to the weightage of the subsequent reveals. Eventually, the considerate, son-loving cop becomes a corrupt assailant and an inhumane, cynical lawyer becomes the moral mediator of truth. Thus, emotions ride on the prejudices projected on individuals rather than factually charged statements.

Also Read: (Un)Controlled Chaos and Herd Mentality in the Films of Lijo Jose Pellissery

One cannot dismiss the nationalistic tendency within the film with the title in itself being labeled the national anthem of the country and its attempt in being multilingual and pan-Indian in existence. There is one scene in particular where Swaminathan points out incidents of injustice in different states of the country and ultimately states that these didn’t happen in different places, but in one place; India. Additionally, the overt antagonization of the leader of the women’s commission which makes her seem unidimensional and caricaturish, savior of the victims by seemingly upper-caste personnel like Swaminathan, and predominant framing of non-Malayalee characters as the bad guys (while Kumar is technically an antagonistic character, he is provided opportunities to redeem himself), the transition from a political drama to an overtly commercialized courtroom thriller are some examples where the film loses its focus in being a credible political film.

Mohammed and Antony denounce a form of justice that is emotionally charged and reactionary and calls for democracy to hold to its values of a detailed system. However, the filmmakers ensure that they are not all that trustworthy of the system itself as the institution of knowledge fails, the institution of law upholding fails, and the institution of information fails. The film becomes a recourse against hegemony enforced through institutional manipulation and exposes that such incidents are not isolated and are a result of the collective failure of an interconnected machinery that weaponizes identity politics for votes. Thus Jana Gana Mana sensitizes its audience to pause before action but doesn’t really instigate how to react.

Jana Gana Mana (2022) Links: IMDb, Wikipedia

![The Greatest Beer Run Ever [2022] Review – A clumsily mounted and glib anti-war movie](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/The-Greatest-Beer-Run-Ever-Movie-Review-2-768x512.jpg)