One of the most heart-numbing films on grief and death would be Michael Haneke’s “Amour” (2012). “Amour” remains firmly entrenched on my list of evergreen films, and I recall watching it without spoilers. The outstanding portrayal of an older woman with dementia by the late Emmanuelle Riva and the breadth of emotion displayed by the late Jean-Louis Trintignant was priceless. With modest inspiration from “Amour” and featuring an Asian twist, filmmakers Tzu-Hui Peng and Ping-Wen Wang craft a tale in A Journey in Spring (Chun xing) that gives viewers an alternative viewpoint on what it means to lose a loved one.

Khim and Tuan are married couples who live together in their imperfect home. Despite doing everything that is feasible for someone of their age, they appear to be struggling financially. We see Tuan working very hard to make what little money she can by collecting used plastic bottles to recycle. As for Khim, he has a limped foot that doesn’t allow him to handle heavy jobs, yet he doesn’t complain much about his disability. They have to take care of their own living expenses since their son, Kian Beng, hasn’t visited them in years. On a regular morning, Khim tries to wake up Tuan and realizes that she is not moving an inch. The process of Khim handling Tuan’s loss makes up the rest of the narrative.

The director duo pins their primary emphasis on the dysfunctionality among aged couples, which is clearly seen in Khim and Tuan’s frequent arguments. Viewers can observe Tuan’s anguish as she constantly criticizes and whines about insignificant matters. For instance, a broken pipe in the kitchen, which was Khim’s responsibility to repair, becomes the cause of a rift between the couples. The tension escalates into a verbal dispute as Tuan begins to raise her voice and accuses Khim. “You may blame God if you want” seems to be Khim’s way of normalizing resentment from his wife. In addition, Khim begins to respond to her with sarcasm, indicating that he is unable to handle these conflicts.

One might see this as an indication of an imbalance between the Yin and Yang energies. However, their degree of disagreement doesn’t appear to go beyond hurting each other, but it does seem to aid them routinely to release their inner depression. As a positive side note, viewers would also see how the couples’ love has grown stronger over the years despite the rifts that have existed between them. Listening to Khim and Tuan’s inside jokes about TV shows and laughing as they reminisce about happy moments help one to feel the intimacy of their love for one another. The filmmakers offer us a fascinating portrait of imperfect love, where certain flaws actually enhance relationships to a greater level.

“A Journey in Spring” also touches on a secondary theme: the declining responsibility of children to care for their aging parents. For many aged parents, the dream of a long and healthy life with their children and grandkids remains unattainable. Throughout the narrative, numerous emotionally charged moments convey Khim and Tuan’s unwavering concern for Kian Beng.

The sentimental value that Tuan places on her son’s old clothes from his childhood and the significance that Khim places on the memories of their son’s wedding are some of the few examples. However, Khim and Tuan have been profoundly affected by Kian Beng’s absence from their lives in different ways. The director duo masterfully demonstrates how acceptance and denial serve as coping mechanisms after a loss, where one person may be waiting for their return while the other has already moved on.

This effect of loss is also evident in the death of Tuan, where Khim falls into the denial stage and begins to make irrational decisions. The aspect of guilt manifests throughout the grieving phase when Khim starts to see how Tuan’s persistent nagging is really a blessing in disguise. Amidst the silence, the incessant internal monologue of whether Khim has been a decent husband to his wife follows him till he can’t tear his eyes away from her. Aside from an emotional drama, the directors also showcase poverty’s darkest aspects, where sudden events bring out unforeseen expenses. The process of how Khim handles all these struggles will shock the viewers indefinitely.

More intrusive questions begin to appear as the film progresses. Is the modern age of globalization a cause for marital estrangement? As a parent, is it wise to put your faith in your children to fulfill your little desires? Does a child’s reluctance to connect with their parents stem from internal conflict or traumatic experiences in their past? What measures has the government adopted so far in order to address the problem of poverty among older people? When faced with the loss of a loved one, how can one go from a state of denial to acceptance?

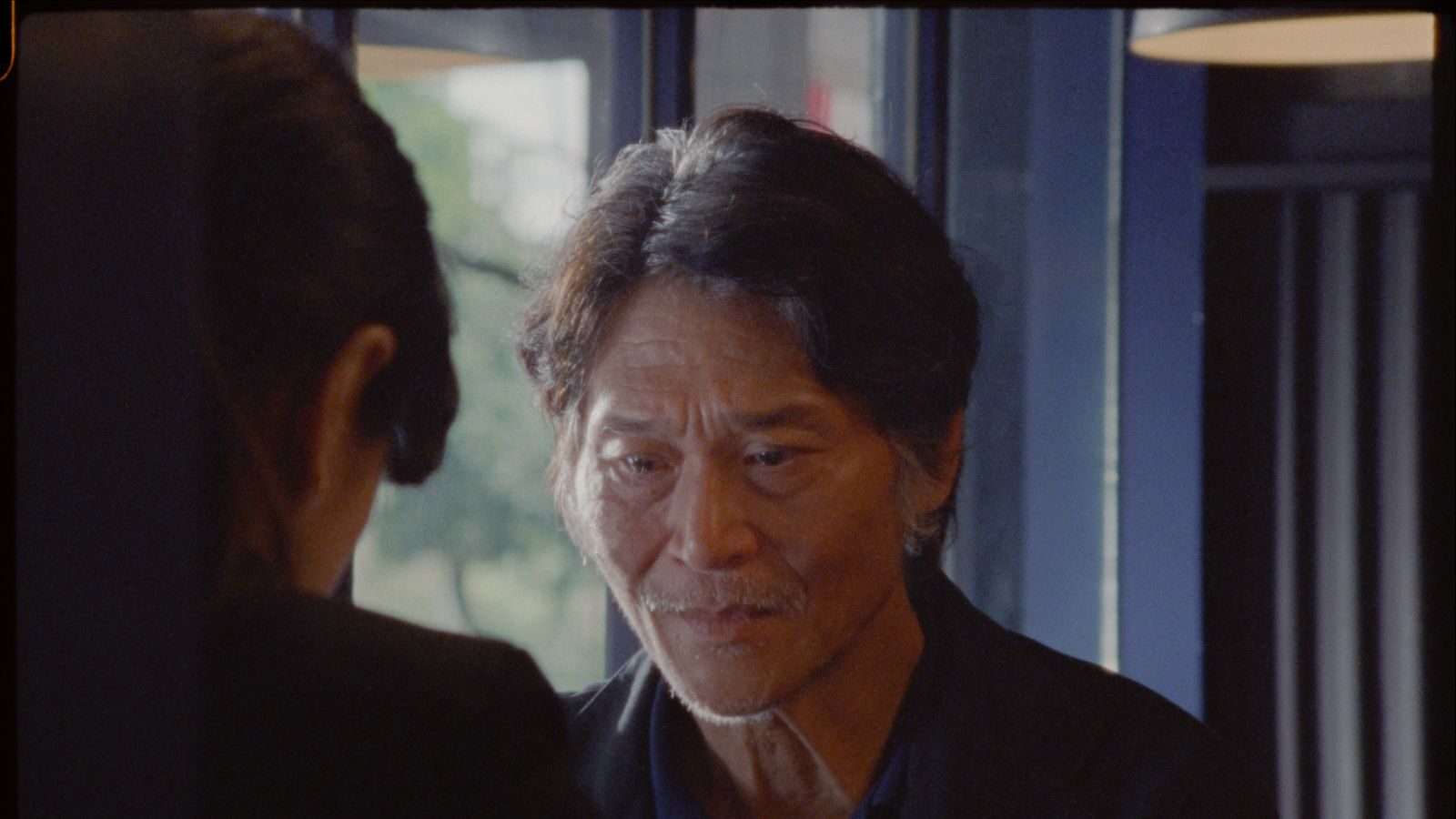

Jieh-Wen King’s performance as Khim is remarkable, as we are able to grasp his despair through his silence. The scene where Kian Beng asks Khim to move in with him, while Khim refuses and limps alone by the side of the road, is probably one of the notable segments of the film. The intensity of Khim’s agony at seeing Tuan’s ashes and his outburst of sorrow may move us to tears. Directors Tzu-Hui Peng and Ping-Wen Wang deserve praise for conveying a bereaved person’s emotional imbalance accurately, which will prompt us to reflect on it long after the credits roll.

“A Journey in Spring” won the Best Actor award and FIPRESCI Prize at the Hong Kong International Film Festival 2024, followed by the Best Director Award at the San Sebastian International Film Festival last year. It is a heartbreaking family drama that takes you on an emotional roller coaster through the challenges of loving people for who they are and the pain of losing a loved one. The film discusses the importance of family, the unpredictable nature of family dynamics, the flawed nature of human beings, and the significance of appreciating every moment spent alongside the people you care about. Despite dealing with heavy themes like death and the profound sadness experienced by bereaved individuals, the delicate and nuanced direction facilitates the narrative to flow like a gentle breeze. Perhaps this is Taiwan’s proud answer to “Amour.”