Abbas Kiarostami stands as a towering figure to have emerged from the rich landscape of Iranian cinema, whose poetic vision and innovative filmmaking have left an indelible mark on the seventh art. From his early days as a graphic designer to his emergence as a leading voice of the Iranian New Wave, Kiarostami’s journey was one of constant evolution and artistic exploration. He has crafted a cinematic language that is both instantly recognizable yet endlessly surprising, with cameras lingering on long contemplative shots, inviting viewers to lose themselves in the rhythms of everyday mundane life. The line between fiction and reality frequently blurs in his work, with non-professional actors sometimes playing versions of themselves and real-life events serving as springboards for profoundly philosophical inquiries.

But despite the closeness to the real, Abbas Kiarostami was never a documentarian in the traditional sense, with his filmmaking aesthetic always decidedly cinematic despite framing actual events. His camera’s patient gaze captured the vastness of Iranian landscapes, mirroring the internal journeys of his characters. He wasn’t afraid of silence, using it to create moments of profound intimacy and encouraging contemplation. What sets Abbas Kiarostami apart is his unwavering faith in the intelligence of his audience: eschewing conventional narrative structures and easy resolutions, he invites the audience to actively engage with the filmed material instead of passively consuming the same.

Below, we shall explore ten of the best films from Abbas Kiarostami’s rich and illustrious oeuvre. Enjoy!

10. Like Someone in Love (2012)

Kiarostami’s second film outside Iran, and the final work to be released within his lifetime, “Like Someone in Love” is set in neon-drenched Tokyo where a young woman named Akiko (Rin Takanashi) navigates a double life: university student by day high-end escort by night. One night, she’s sent to visit retired professor Takashi (Tadashi Okuno), a widower with a hint of melancholy in his eyes who seems more interested in cooking, talking, and Ella Fitzgerald records rather than having sex with Akiko. Takashi’s paternal demeanor contrasts sharply with Akiko’s youthful turbulence. He offers her a place to sleep, cooks for her, and drives her to her university the next day, where they encounter Akiko’s obsessive boyfriend, Noriaki (Ryo Kase).

Kiarostami’s masterful framing heightens the film’s atmosphere of intrigue fused with melancholy. We often see characters through windowpanes or reflections, creating a sense of voyeurism and distance. The director’s penchant for filming conversations through car windows creates a sense of both intimacy and detachment, mirroring the characters’ emotional states. Kiarostami’s refusal to provide easy answers or neat resolutions can feel frustrating, but it’s precisely this ambiguity that gives “Like Someone in Love” its lasting power. Takashi’s kindness could be genuine affection or perhaps a desperate attempt to recapture a lost youth, while Akiko’s responses are equally ambiguous. The film’s title, borrowed from an Ella Fitzgerald song, hints at the illusory nature of the characters’ interactions, suggesting that they might only be “like someone in love” rather than truly experiencing the same.

9. Ten (2002)

Shot entirely from the dashboard of a car driving through the bustling streets of Tehran, “Ten” offers an intimate glimpse into the lives of modern Iranian women, their struggles, and their resilience. Through ten vignettes, we observe the interactions of an unnamed driver (Mania Akbari) with various passengers, each providing a different lens on life in contemporary Tehran. The passengers include her son Amin (Amina Maher), her sister, a sex worker (Roya Akbari), a bride, and an old woman. Each conversation reveals layers of the characters’ lives and offers insights into their broader societal issues. The driver’s precocious and often combative young son Amin is featured most prominently, their heated exchanges laying bare the generational and gender divides that run deep in Iranian culture.

Armed with just two digital cameras fixed to the car’s dashboard, Abbas Kiarostami creates a sense of claustrophobia and immediacy that draws us into these deeply personal conversations. The constrained setting becomes a metaphor for the restrictions women face in Iranian society while also serving as a confessional space where passengers feel free to open up. We meet a devout old woman heading to prayer, a sex worker negotiating the dangers of her profession, and a heartbroken young woman reeling from a breakup. The central character of the driver herself emerges as a divorcée grappling with societal judgment, motherhood, and her own sense of identity. Each encounter adds another brushstroke to the portrait of contemporary Iran that Abbas Kiarostami is painting in a masterclass of minimalist filmmaking.

8. 24 Frames (2017)

In his final masterwork, Abbas Kiarostami strings together a series of breathtaking vignettes, brought to life by CGI and animation and accompanied by carefully curated pieces of music. Pushing the boundaries of what experimental filmmaking can achieve, Kiarostami injects life into 24 still photographs to guide our imagination (but also let it run wild) as the static frames metamorphose into moving imagery. The film opens with Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s painting “The Hunters in the Snow,” setting the tone for what’s to come. As the snow begins to fall and a dog ambles across the foreground, we’re immediately thrust into Kiarostami’s world, where the static becomes dynamic, and the familiar gets estranged. Released posthumously, this experimental work serves as a fitting capstone to the career of one of cinema’s most innovative auteurs, challenging our perception of time, movement, and the very nature of images.

Humans are rarely seen directly (except in Frames 15 and 24), but their presence is intermittently felt across the quasi-narratives in the form of gunshots, chainsaws, and automobiles. There isn’t much sense in labeling it as an ‘Iranian film’ or placing other similar genre markers, for it is more of a personal love letter from Kiarostami to the medium of cinema and all its infinite possibilities. Like the twentieth-century avant-gardists scratching and bleaching celluloid in search of newer ways of constructing films, Abbas Kiarostami works in reverse by embracing the power of digital imagery and using it to add a temporal dimension to natural images frozen in time. In his own way, he pays homage to the art of videography without making use of it; he recognizes its transformative power within the framework of art.

7. The Wind Will Carry Us (1999)

“Entrust your lips, replete with life’s warmth,

To the touch of my loving lips

The wind will carry us

The wind will carry us!”― Forough Farrokhzad

“The Wind Will Carry Us” quietly sneaks up on you rather than asserting its intentions outright, much like its protagonist, Mr. Behzad (Behzad Dorani), a Tehran-based journalist who visits a remote Kurdish village on a mission that isn’t readily apparent. One best goes into this film, knowing as little of the plot as possible, as it ever-so-slowly trickles out information to keep us looking and observing intently, keeping us in the dark about Mr. Behzad’s motives as much as the villagers. Kiarostami is said to have keenly studied Bresson while producing this film, and it readily shows. He keeps a great deal hidden away from our sight, perhaps to stir our imagination and encourage involvement, like Mr. Behzad’s two companions or the man digging a ditch, none of whom ever appear onscreen.

Related to Abbas Kiarostami Movies: 20 Underrated Road Movies You Need to See

The title sequence, inspired by Farrokhzad’s poetry, features a brilliant interplay of light and dark where a woman milking cows refuses to show her face despite Behzad’s repeated instigations. Kiarostami’s spare treatment leaves us focusing intently on our protagonist and his relationship with this village, where he seems like a fish out of the water with his camera, his cellphone, and his refined intellectual sensibilities. Behzad appears a little condescending to the villagers initially, and his lack of respect is on clear display as he pokes humor at everything these people hold sacred, but the rustic wisdom held by them continues to chip away at his irreverence.

During his stay, Behzad observes a birth and a death and people caught in various stages of life between them, and through his eyes, we are given an abridged reflection of life in this remote, half-forgotten village. By the end of the film, we can feel that Behzad (and, with him, the audience) has started caring for these people and is maybe even a tad embarrassed as he spends his final couple of days trying to make little amends for his erstwhile self-centered behavior.

6. Certified Copy (2010)

As captivating as it is confounding, “Certified Copy” is set against the picturesque backdrop of a sun-drenched Tuscan town where we follow the chance encounter at a gallery between British author James Miller (William Shimell) and an unnamed French antique dealer played by Juliette Binoche. James is in town to promote his new book ‘Certified Copy,’ which argues for the blurring of conceptual boundaries between copies and originals, insisting on how every original is also, in turn, a copy of something that came before. The woman, attending the event with her 11-year-old son, later invites James on a drive through the Tuscan countryside. What begins as a spirited debate about art and authenticity soon morphs into something far more complex and emotionally charged.

As the day unfolds, the line between reality and performance begins to blur. At one point, a café owner mistakes them for a married couple, and they begin playing along instead of correcting her. This role-playing fiction is sustained even after they’ve exited the café. Are they truly strangers, or do they share a deeper, hidden past? Abbas Kiarostami basks in this ambiguity as his camera closes up on faces, inviting us to scrutinize their expressions for clues to the “truth.”

He lingers on seemingly mundane details – a stray hair on the woman’s jacket, the way James stirs his coffee–which are imbued with a strange significance as if holding the key to help us differentiate authentic from fake. Ultimately, it is the fluidity of identity and the fraught concept of authenticity, in both art and relationships, that is centrally at stake in “Certified Copy,” challenging us to consider whether genuine connections and feelings can emerge from what might initially seem like mere imitations or performances.

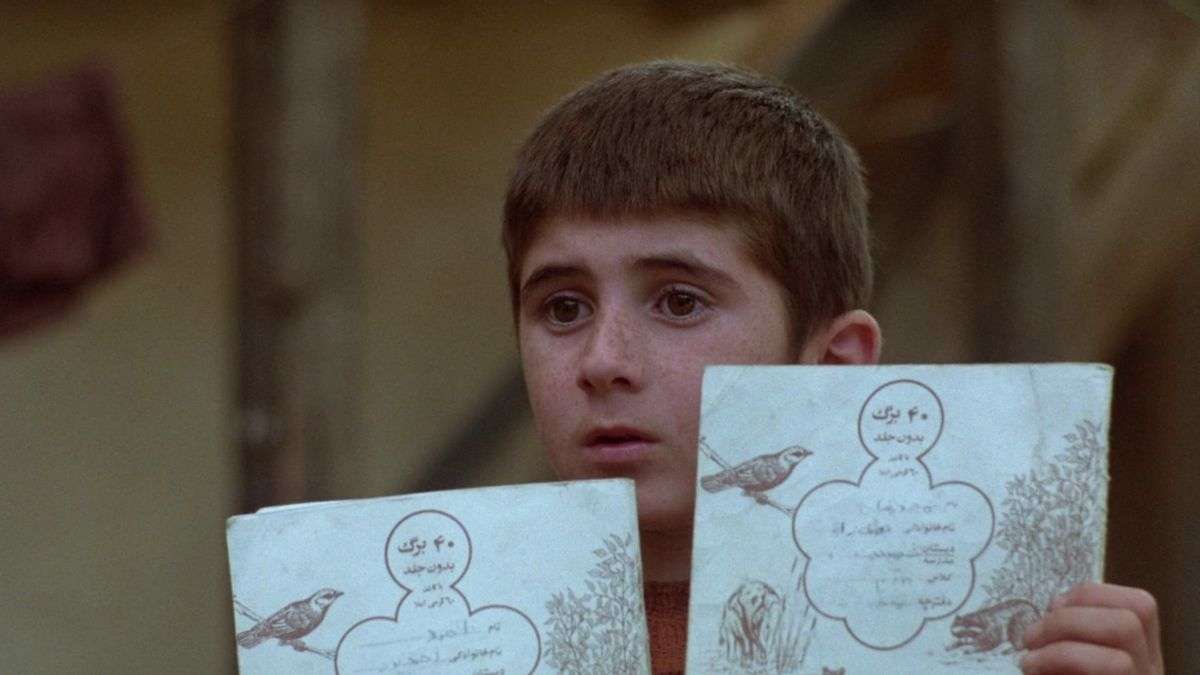

5. Where Is the Friend’s House? (1987)

The first film in Kiariostami’s famed Koker trilogy is a deceptively simple masterpiece set in the rural village of Koker, exploring childhood innocence, responsibility, and the oft-overlooked acts of everyday heroism. Ahmed (Babak Ahmadpour) is an eight-year-old boy who has accidentally taken home the notebook of his classmate Mohammad Reza (Ahmed Ahmadpour); the latter is threatened with expulsion from his school for repeatedly failing to do his homework. Ahmed thus embarks on a determined quest to return the notebook before nightfall, despite the challenges posed by the strictures of his small community and his family’s expectations.

From a carpenter too busy to help to an old man who provides advice but no real assistance, Ahmed’s encounters along the way highlight the bureaucratic and often indifferent nature of adult society, in stark contrast to his own childlike zeal to help his friend. His journey becomes an adventure, filled with detours and unexpected encounters. Kiarostami’s masterful use of non-professional actors adds to the film’s realism, in addition to conversations being peppered with local dialects and everyday mundane concerns. “Where Is the Friend’s House?” keeps toying with the line separating fiction from documentary, drawing the viewer into Ahmed’s world with a genuine sense of immediacy. Abbas Kiarostami never condescends to his young protagonist or resorts to sentimentality but instead presents Ahmed’s quest with utmost seriousness, respecting the weight it carries in the boy’s little world.

4. And Life Goes On (1992)

Set against the aftermath of the devastating 1990 earthquake in northern Iran, “And Life Goes On” is a mesmerizing blend of fiction and reality exploring human resilience in the face of catastrophe and the thin line separating cinema from life. It follows a director (Farhad Kheradmand) and his young son (Buba Bayour) as they drive through the earthquake-ravaged landscapes to find the young stars of Kiarostami’s last film “Where Is the Friend’s House?” and check on their safety. The once-vibrant village lies in ruins, homes reduced to rubble, and a sense of collective grief hangs heavily in the air. Despite the overwhelming destruction, the film focuses on the small acts of kindness and the cooperative resistance to cataclysmic threats on the part of the villagers.

While never transgressing the boundaries of being exploitative of grief, Kiarostami nevertheless doesn’t shy away from representing the harshest realities. His long contemplative shots capture the wreckage and the survivors, their faces etched with loss but also a quiet determination to rebuild. Kheradmand, in the role clearly meant to represent Abbas Kiarostami himself, delivers a nuanced performance that captures both the determination and the growing bewilderment of a man confronting nature’s awe-inspiring destructive power.

Kiarostami’s penchant for off-screen action and dialogue adds layers of depth to the narrative, forcing us to imagine the full scope of the disaster beyond what’s merely caught on camera. What’s truly remarkable about “And Life Goes On” is how it finds hope and even humor amidst the rubble. A young couple, determined to get married despite the chaos, becomes a recurring motif – their love story a testament to life’s persistence, in turn becoming the subject for Kiarostami’s subsequent film.

3. Through the Olive Trees (1994)

This mesmerizing conclusion to Kiarostami’s Koker trilogy is a meta-cinematic gem whose layered narrative makes the viewer ponder the nature of storytelling alongside the persistence and mysteries of human desire. Set in the same earthquake-ravaged village of Koker from “And Life Goes On,” the film follows the production of a follow-up movie – a fictionalized account of the events following the disaster. We see Hossein (Hossein Rezai), a young illiterate construction worker, cast as an actor who is hopelessly in love with his co-star Tahereh (Tahereh Ladanian). Their on-screen romance mirrors a real-life pursuit, as Hossein repeatedly proposes marriage to Tahereh between takes, only to be met with stony silence.

Mohammad-Ali Keshavarz plays the fictional director (another stand-in for Kiarostami himself) whose frustrated attempts to capture the perfect take become a metaphor for the elusive nature of truth in both cinema and life. Is Hossein’s pining for Tahareh genuine, or is it simply part of his performance? The olive groves that give the film its title become a character in their own right, their gnarled trunks and silvery leaves bearing silent witness to the human drama unfolding in their midst. Enhancing the film’s introspective mood is the beautifully evocative cinematography, capturing the lush rolling hills and, of course, the olive trees. In one unforgettable sequence, Kiarostami’s camera follows Hossein as he pursues Tahereh through these groves, their dance of attraction and rejection playing out against a landscape that has endured far greater upheavals.

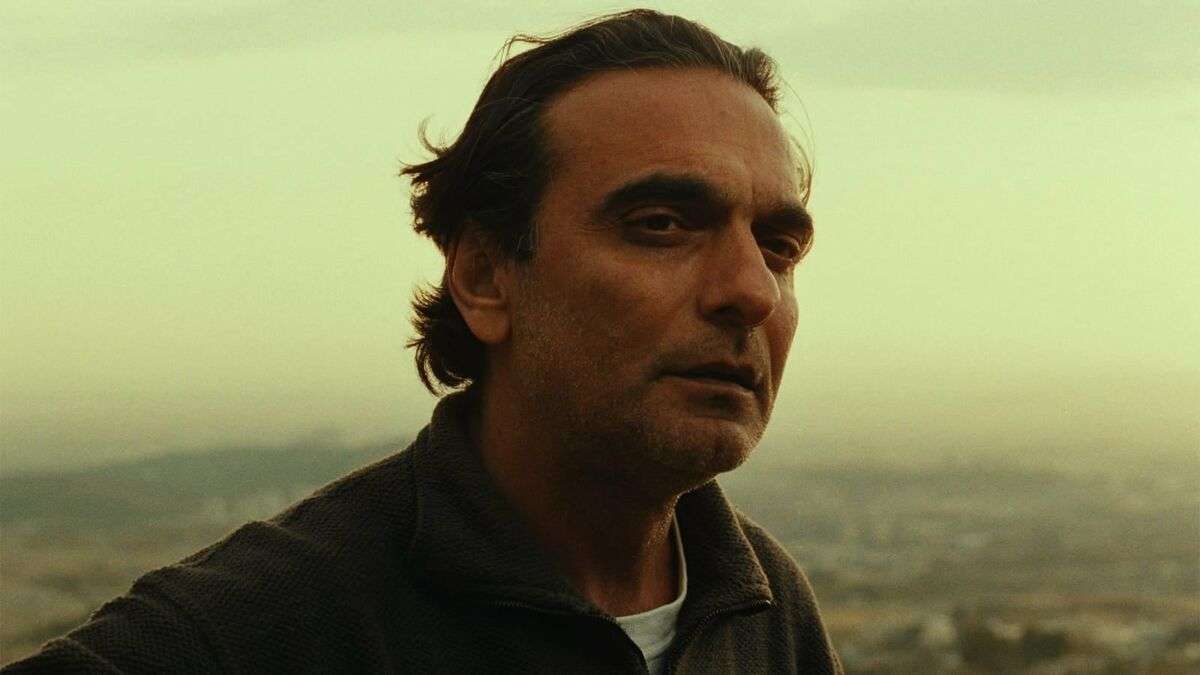

2. Taste of Cherry (1997)

Kiarostami’s Palme d’Or-winning “Taste of Cherry” (1997) is a haunting meditation on life, death, and the existential despair in between. The film follows Mr. Badii (Homayoun Ershadi), a middle-aged man driving through the barren hills of Iran with a macabre purpose: he’s searching for someone to bury him after he kills himself, a taboo act in Islam. Ershadi’s nuanced performance is a marvel of restraint, his weathered face a canvas of quiet desperation that speaks volumes without saying a word. As Badii encounters various individuals – a young Kurdish soldier (Safar Ali Moradi), an Afghan seminary student (Mir Hossein Noori), and a Turkish taxidermist (Abdolrahman Bagheri) – Abbas Kiarostami turns each interaction into a profound exploration of morality, faith, and the value of human life.

Each character he encounters offers a different perspective, reflecting diverse cultural and personal viewpoints on death and the worth of human life. The Kurdish soldier’s fear, the seminarian’s religious objections, and the taxidermist’s pragmatic yet life-affirming philosophy all contribute to a rich and complex existential discourse. The barren landscape becomes a character in its own right, its endless hills and construction sites mirroring Badii’s internal desolation. We’re never told why exactly Badii wants to end his life, nor are we given a clear resolution to his quest. Instead, Kiarostami invites us to grapple with these questions ourselves, turning the film into a deeply personal experience for each viewer.

1. Close-Up (1990)

Based on a bizarre real-life incident, “Close-Up” recounts the strange case of Hossain Sabzian (playing himself), who impersonated the famous Iranian filmmaker Mohsen Makhmalbaf. Sabzian, a cinephile and Makhmalbaf devotee, convinced the well-to-do Ahankhah family that he was the renowned director scouting locations for his next film. With his deception eventually uncovered, Sabzian finds himself on trial, facing charges of fraud and attempted crime. Intrigued by the case, Kiarostami decided to document it, blending real trial footage with reenactments involving the actual people involved. The first half documents the Ahankhahs’ initial encounters with Sabzian, using a mix of reenactments and interviews with the real family members. But the second half takes an even more daring turn when Abbas Kiarostami brings the real Sabzian and Makhmalbaf face to face with the Ahankhahs.

The resulting scenes are electric, filled with a mix of anger, confusion, and grudging respect. The initially defensive Sabzian eventually admits his deception while Makhmalbaf grapples with the strange mirroring of his own identity. Kiarostami’s stroke of genius lies in his decision to have the real people involved in the incident re-enact their own roles. This includes not just Sabzian but also the Ahankhah family, the journalist who exposed the fraud (Hossain Farazmand), and even the real Mohsen Makhmalbaf.

The result is a fascinating hybrid that constantly keeps us guessing about what’s “real” and what’s reconstructed. “Close-Up” seamlessly shifts between documentary and dramatization, creating a layered narrative that challenges the viewer’s perception of truth. We see Sabzian not as a malicious imposter but as a man consumed by his love for movies. His portrayal of Makhmalbaf is riddled with inconsistencies yet also reveals a genuine understanding of the filmmaking process.