For all his significance as a screenwriter, performer, comedian, and musician, it can be easy for some to forget what a wonderfully talented director Woody Allen is when he hits his sweet spot. Said sweet spot is mainly New York Dramedies, centered on the love lives and moral quandaries of the middle classes, and was hit with clockwork regularity during the late-1970s and 80s, a period during which Allen’s prolificacy, consistency, and quality was unmatched.

His status as a prominent voice in American film was galvanized by the wildly influential Annie Hall, which swept four of the five main Oscars in 1977 and remains the benchmark for romantic comedies. This trend continued with classics such as Manhattan (1979), The Purple Rose of Cairo (1985), and Hannah and Her Sisters (1986). Indeed, Allen was nominated for Academy Awards with alarming frequency and has recorded 16 nominations in the Best Original Screenplay prize to date, appropriate considering how delicately his scripts balance caustic wit with hefty themes. 1989’s Crimes and Misdemeanours sees these tones coalesce with startling clarity: a film of two intertwining stories, one a comedy, the other a deathly drama.

With his Brooklyn heritage and background in the worlds of New Orleans Jazz and stand-up comedy, Allen is, by all means, a homegrown American master, but his work nonetheless speaks of a deep-rooted understanding of European arthouse cinema. The names of Ingmar Bergman and Federico Fellini, in particular, come to mind, the former influencing Interiors (1978, Allen’s first drama) and A Midsummer Night’s Sex Comedy (1982), the latter Sweet and Lowdown (1999) and Stardust Memories (1980). That is not to say that his work lacks originality, however. Whilst Zelig (1983) and Husbands and Wives (1992) pioneered mockumentary storytelling, Deconstructing Harry (1997) sees Allen playing against type, as an alcoholic, pill-popping womanizer.

In the 21st century, Allen’s output has not slowed down, but his powers of quality control have begun to wane. Hits such as the quaintly nostalgic Midnight in Paris (2011) have been outweighed by irrefutable duds such as Hollywood Ending (2002). There’s still a charm to his modern works, but it is to his heyday that his fans return, enwrapping themselves in his wonderful worlds of escapism and romance, worlds we will further explore in this ranking of Woody Allen’s ten finest accomplishments.

10. Husbands and Wives (1992)

The final film Allen would make with long-term collaborator and partner Mia Farrow before their publicized separation, “Husbands and Wives” works as both a riveting piece of cinema, in the same vein as all of its directors best dramas, and as an almost uncomfortably engaging gaze through the looking glass into the complicated lives of its central couple.

Allen has always rejected autobiographical readings of his work, but it’s impossible not to interpret this Oscar-nominated effort as such, which uses a shaky-cam, talking heads documentary aesthetic to present a sobering portrait of a mid-life romantic disintegration, the same year that its leads were experiencing one themselves. Removed from the auteur theory, the film still works a treat, as sharply observed in characterizations and observations as ever, dissecting and interrogating the facade that one adopts in a relationship, even a long-lasting marriage. Furthermore, Carlo Di Palma’s cinematography genuinely pushed the envelope forward in terms of the presentation of dramatic comedies at the time, and though Allen himself would never return to that particular style, its influence lingers large on later generations.

9. Midnight in Paris (2011)

It’s no secret among Woody Allen fans and critics that the great director’s output has faltered in recent years, too often playing into the same stereotypes and overplayed narratives, lacking in the originality and intelligence of his finest works. In a way, then, it made it all the more special when the gorgeously realized Midnight in Paris premiered to rapturous applause at Cannes in 2011 and went onto spark something of a mainstream career rival, highlighted by his fourth Academy Award win and, later, 2013’s equally acclaimed Blue Jasmine.

Related to Woody Allen: Midnight in Paris (2011): A Theme Park Ride into Nostalgia and Paris

Though by all means a late-career work, the film’s genesis dates back to the 1970s, where it appears as both a short story and as an undeveloped screenplay, and it’s easy to see where this mildly fantastical fair could have fit in with Allen’s “early, funny films” (ie somewhere in-between Sleeper, 1973, and Love and Death, 1975) but with four decades of experience under his belt, one feels as if Allen is better equipped to comment upon the movie’s themes of nostalgia, artistry, and longing. “Nostalgia is denial”, preaches Michale Sheen’s character Paul who, despite being the typically obnoxious pseudo-intellectual of the piece, is right in that he foreshadows the value of this ultimately bittersweet lamentation on ages past and pastures new, as Owen Wilson’s American write Gil Pender fails to find fulfillment in continuing to revel in borrowed nostalgia for a romanticized past.

8. Radio Days (1987)

Another take on nostalgia, Radio Days is a gem of a film extracted from one of its director’s very best periods of work and remains one of his most ambitious and personal projects. As opposed to Paris in the 1920s, this brand of nostalgia feels far closer to Allen’s heart, as he lovingly narrates this ode to an age where the world of radio in New York City was the beating heart of showbiz.

Shot again by Di Palma in eternally appealing colors, illuminating the shining lights and exuberant wear of the early 1940s, the film is a true exercise in nostalgia to an extent at once shameless and delightful. But whereas modern media tends to define nostalgia as a series of icons, logos, songs, and references, Allen defines it as a more general feeling, something intangible but somehow captured in every scene of the film, which charmingly whizzes around recreations of the anecdotes and folk tales that permeated throughout the pop-cultural landscape. It was one of the first Woody Allen films in which the director didn’t also appear in front of the camera, but as a soothing voice guiding the viewer through this world he has concocted, his familiar personality is more charming and endearing than ever, and his final line remains one of his most potent: “now it’s all gone except the memories.”

7. Annie Hall (1977)

There are more accomplished and moving films in the Woody Allen catalog, but none so pivotal to the direction of cinema history than Annie Hall, which reinvented the rom-com genre with its endlessly witty screenplay, heartfelt performances, and opening monologue, in which a forthright Allen stares down the camera, inviting the audience into a tender, vulnerable and often hilarious delve into the psyche of Alvy Singer. Often cited as one of American cinema’s very best romances, it’s fascinating on a rewatch how Allen manages to dissect the relationship between the two characters by dissecting them as individuals first.

Related to Woody Allen: 10 Greatest Oscar Best Picture Winner

We know Alvy is neurotic and that Annie is eccentric, and the characters are developed so fully that it could be interpreted as the screenplay’s will for them to be seen solely as individuals, that their relationship is untenable — such differing and engaging personalities can sometimes coalesce into one entity, but here they are too enamored to be apart yet too unique to stay together. Beyond all the innovation, Annie Hall is essentially a film of bittersweet resolution; if only they could address each other directly.

6. Another Woman (1988)

Thanks in part to his stellar standup career, and of course the myriad comedy pictures he has made throughout his career, the name of Woody Allen will most likely forever be associated with neurotic, high-minded, and often heartfelt humor, but for a time in the 1980s, the writer-director was proving himself quite the dramatist also. 1988’s Another Woman sees this dramatist incarnation of Allen at the peak of its powers. Sandwiched between the Chekhov-inflected September (1987) and the finely tuned Crimes and Misdemeanours (1989), it is perhaps the most self-serious and drab offering of the auteur’s entire filmography but manages to stick the landing as a deeply poignant piece of filmmaking thanks to a staggering central performance by Gena Rowlands and, as ever, Allen’s ingenious screenplay, as well as his direction, which switches protagonist Marion’s emotions from the concrete (her blunt narration) to the abstract.

This combined with Sven Nykvist’s beautiful deep-focus photography makes a strong case for Another Woman also being Allen’s most formalist movie, forging the components of this character study through craft alone, though the philosophical nature of many of his movies at the time never strays far from the lens. As the narrative progresses, Marion’s ability to tell the truth of her life from a play her ex-lover has written about her dwindles, and several scenes of ethereal beauty (backed by Erik Satie’s Gymnopédie) pay direct homage to perennial influences, Brecht and Bergman, evoking a level of the cerebral exclusive to the medium’s more subjective, purely emotional impulses.

5. Deconstructing Harry (1997)

Of all the films on this list, Deconstructing Harry is the least canonized among critics and audiences, but this bitter, acid-tongued trip down memory lane stands as the last absolute masterpiece its director would ever make. An often vulgar re-interpretation of Bergman’s Wild Strawberries (1957), Allen himself here excels most in front of the camera, as the titular Harry Block, a pill-popping, depressive writer whose literary success earns him honor at the very school he was once expelled from, and embarks on a road trip to the ceremony with his kidnapped son, dying friend, and an outspoken prostate.

Related to Woody Allen: Allen And Cinema As The Opium of the Masses

Hardly the most conventional of plots, but once has already appreciated the hilarious one-liners and unique interplay between the performers on first viewing, upon revisiting one can fully engage with the breadth and depth of the issues Allen is dealing with. In moments of innovation, we see Block discussing his travails with his own creations, themselves reflections of his psyche, his loves lost and past lives lived. The ending is the deciding sucker punch: Block stands slouched, almost paralyzed with depression, facing an array of his characters, purposefully resembling figures in his own life, and realizes that the true beauty of his existence, underpinning and outlasting the hedonism and nihilism with which he surrounds himself, is his work, in which he can express true feelings and embolden the world.

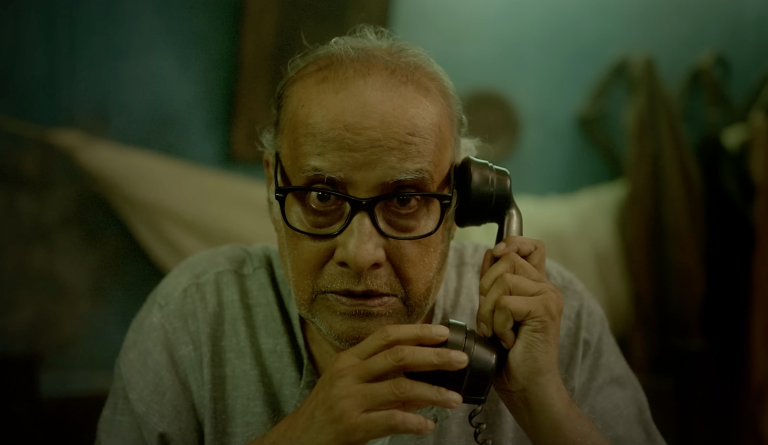

4. Crimes and Misdemeanors (1989)

The thin tightrope between drama and comedy is something that Woody Allen has consistently walked throughout the years, and never with such delicacy and cerebral weight as in Crimes and Misdemeanors, whose structure is an almost parodically literal interpretation of the ‘Dramedy’. In short, there are two conflicting stories: one a romantic comedy; one a deathly drama. On paper, they seem entirely separate in tone and execution, but through some of his smartest dialogue and narrative ordering, they coalesce into a beautiful whole. The significant thematic punch of the picture is emphasized by a truly stark ending, the finest in Allen’s filmography, in which Allen and co-star Martin Landau finally cross paths.

Many films on this list raise larger than life philosophical, existential questions about existence, behavior, love, guilt, romance, but leave them largely, purposefully, unanswered. In Crimes and Misdemeanors Allen finally provides something of an answer, not one I’m willing to spoil, but one that suggests that if there is a God is he truly one worth worshipping in a world of such hatred and bad luck? This question is raised with a typically deft touch and reinforced by Sven Nykvist’s impeccable cinematography and least half-a-dozen performances of skill and nuance. Rightfully considered one of his finest achievements.

3. Stardust Memories (1980)

From Greenaway’s 8 1/2 Women to Fosse’s All That Jazz, many a filmmaker’s artistic flame has been set alight by the magic of Fellini’s landmark 8 1/2, though only Allen’s Stardust Memories has come close to capturing the magic of the original. The writer-director achieves this through boldly naked self-reflection, casting himself as Sandy Bates, an acclaimed comedian-cum-director fighting for his sanity’s survival in a weekend at the titular Stardust hotel. So far, so Fellini. But by imbuing this sense of humor and wonderful understanding of human relationships Allen manages to sparkle the necessary, titular, stardust onto the screenplay, creating an entirely new work that transcends pastiche and lampooning and becomes an essential entry into his filmography. The film was met with critical befuddlement in its day, even from close friend Pauline Kael, but it’s telling that Woody himself, so long a vehement critic of his own work, has always harbored a soft spot for Stardust.

Related to Woody Allen: 6 Best Federico Fellini Movies

In his autobiography, he once again dissuades viewers from an autobiographical reading but does comment upon the fraught triad of critics, fans, and artists that comprise the film industry. Many critics of the time complained of a supposedly arrogant Allen using his platform to bemoan his own fanbase who support him, but he was trying to point to a much more subtle argument about the dangers of parasocial relationships between artists and audiences, albeit in the most obvious way possible as Sandy Bates is shot by his own admirer. Shortly after the film’s release, John Lennon was shot, making Allen feel vindicated in his own commentary on the sad state of the world of celebrity. Ultimately, though, Stardust Memories is a film of sumptuous visual beauty and bittersweet romance — a tale of caution and commentary rather than abject nihilism.

2. Hannah and Her Sisters (1986)

Woody Allen’s warmest, most life-affirming film, Hannah and Her Sisters has a deserved place in the canon of ‘80s cinema as a masterpiece of human interaction and nuanced emotion, woven intricately through several overlapping storylines, each centered on a member of an extended New York family. Buoyed by Carlo Di Palma’s gorgeous deep-focus cinematography and an array of marvelous performances (both Dianne Wiest and Michael Caine won Oscars for their roles), the screenplay (another Oscar winner) is truly masterful in the way it balances tone, thematic weight, and the time spent with its central characters. Each scene is more riveting than the next, but the true beauty of Allen’s film is found not in its undeniable technical prowess but the pure emotional resonance and universal beauty of the screenplay and how it is delivered.

The most impactful example of this may be a famous monologue delivered by Allen’s depressive TV producer Mickey, detailing his brushes with suicide and eventual enlightenment at the movie theatre, a speech so potent it reaches beyond Woody’s typical brand of cynicism and snark and into a realm of hope for the world and existence. Buy and large it has a similar message to the more bitter Deconstructing Harry but is presented with far more warmth and appreciation for its characters, representative of a different time in Allen’s personal and professional life: a perfect coalition of all his greatest characteristics as a writer, director, and performer.

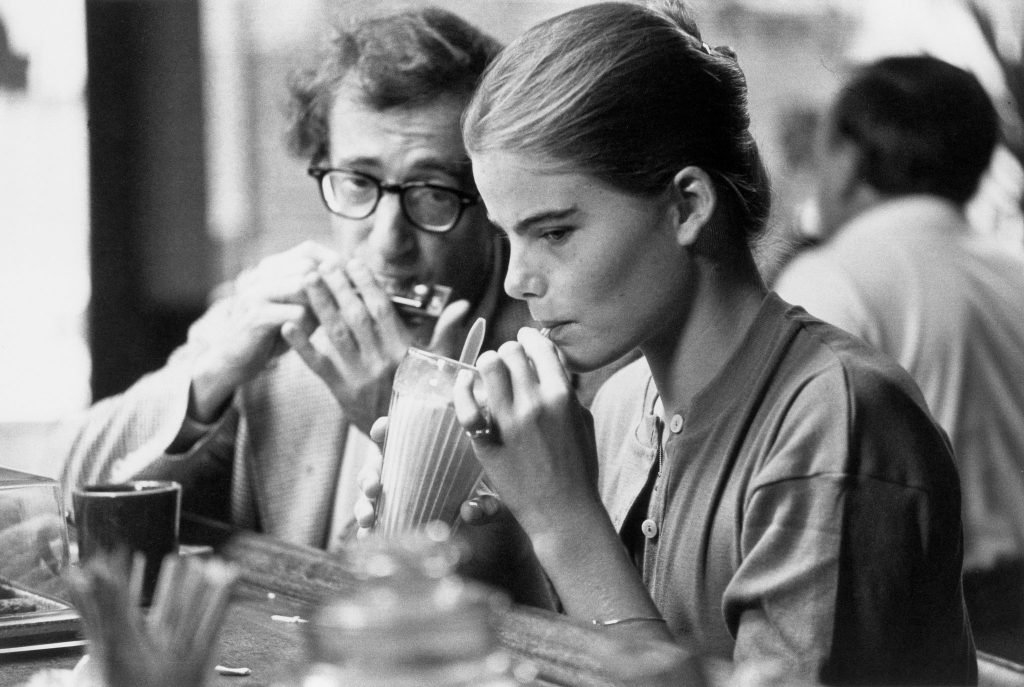

1. Manhattan (1979)

Put simply, Allen’s masterpiece. Shot in gorgeous black-and-white by Gordon Willis, made to evoke protagonist Isaac’s childhood memories, Manhattan is a delightful, bittersweet ode to younger women, promiscuity, and the New York borough it was named after. It’s perhaps the best summary of Allen’s most prevalent thematic touchstones but also best exemplifies his skeptical worldview, which once blown onto the biggest of screens in the prettiest of colors, becomes wondrous. The tale of a middle-aged man’s back-and-forth relationships with his best friend’s mistress (Diane Keaton) and a 17-year-old student (Mariel Hemmingway), the film tackles an extremely taboo subject matter without passing judgment or preaching to the audience.

Related to Woody Allen: 20 Best Movies About Writers

Rather than being a celluloid op-ed, it is an observant piece, but not to the extent where Allen and co-writer Marshall Brickman ever lose a genuine emotional connection with the characters. Both central romances may be inherently doomed, yet they feel so authentic and raw in their dialogue (the witty exchanges, quotable one-liners) that the audience believes fully in their passion, and engaged in the possibility that one of them might come good. It’s some of Allen’s very smartest screenwriting, and it benefits from the grand cinematic scope of the project, despite the relatively small-scale of the project. Many Allen films, for all their brilliance, could work almost just as well as radio plays or in the theatre, but the cinematography, editing, and swooning music of Manhattan are truly emblematic of the power of the medium, and a testament to the beauty and diversity of its titular location. One of the greatest images of the human heart and the cityscape ever captured.

What a shity list without Match point!