The conceit of Leonard Cohen’s ‘Is This What You Wanted’ is to self-deprecate at the cost of showing his soon-to-be ex-wife’s superiority. In one line, he says ‘You were Marlon Brando, I was Steve McQueen.’ This witty comparison upholds an indisputable idea – that McQueen, then Hollywood’s biggest box-office star (or any ‘star’), could never hold a candle to the finesse and brilliance of Marlon Brando. Indeed, perhaps no one in American cinema’s history can, to a man whose monumental ability and revolutionary methodology could never be put into words because of how natural it all was to him.

He was described by Los Angeles magazine as ‘rock and roll before anybody knew what rock and roll was’, whose real-life histrionics were the only competition for his theatrics onscreen. Yet few actors have ever allowed their bearing to bolster greater social causes, be it walking down Harlem with Mayor Lindsay the night Martin Luther King Jr. was shot or sending an Apache woman to reject an Academy Award for a role that revived his career. The myth of Marlon Brando exceeds any encapsulation and attempts to separate his genius as an artist from his recklessness as a man, are folly. He is a singular figure in cinema history, whose disdain for ‘stardom’ ironically redefined what it means to be one.

10. Julius Caesar (1953)

Released at a time when Welles’s Expressionist adaptations of Macbeth and Othello had changed the perception about how radically the most revered texts in the literary canon could be adapted for the screen, Mankiewicz’s film is a somewhat overlooked gem from the 1950s. Remembered mostly as being one of the series of terrific films that announced the arrival of Marlon Brando, it certainly is an excellent work in its own right. With its staging and visual flourish, counting it as being among the best film adaptations of Bard’s texts is not a stretch. Its cast included some of the most gifted acting talents in the world at the time, like Edmond O’Brien, Deborah Kerr, Sir John Gielgud among a host of others.

Similar title to this Marlon Brando Film: Hail, Caesar! (2016) – A Hilarious Faux Pas on Hollywood

As Brando makes his proper appearance in the wake of Caesar’s death, he hides Antony’s conflict with steadfast assuredness. Given the stage at his funeral, he becomes Brutus’s greatest mistake, delivering a speech with such fervor that Brutus’s reason pales in comparison to Antony’s evocation of sentiment. Brando measures every turn in his audience’s heart, screams with vigor, and weeps with deceit. Every sound, every move is painstakingly measured. His Machiavellian side is revealed through stares and gestures as he proves himself a far more cunning politician than Brutus imagined. Then, like a master conductor building up to the crescendo of a sonata, the ending of his speech with ‘Here was a Caesar. When comes such another?’, embodies a magnetism so infectious that the scenes that follow somehow fall flat in comparison.

9. The Wild One (1953)

The setting of a small dreary town where the arrival of a group of outlaws causes mayhem means it’s really a Western in disguise. Brando’s iconic look from the film in his leather jacket, sideburns, and tilted cap has remained one of cinema’s enduring symbols of style and swagger, inspiring Elvis to Alex Turner, and it is what the film, too, is largely remembered for. Yet it’s shallow to overlook the potency of its exploration of lawlessness. Made three decades before ‘Do The Right Thing’, it is a disturbing depiction of the catastrophe that unfolds when a problem is exacerbated uncontrollably by remaining unchecked.

Brando’s performance is no different than that of a cowboy. As Johnny, he is not entirely an admirable character, yet his charisma shines through. He carefully ensures that the cavalier machismo never turns brutish or coarse, but instead has a softness that only needs to be evoked. He is aware of the importance of Johnny’s style, his gait, and postures, and deliberately allows it all to define the character’s facade. The iconic statement about rebelling against everything is the paragon of coolness. Then, through Kathie Bleeker’s character, the revelation of this veneer’s falsity begins, most noticeably in the park scene. Through a portrayal of this duality, it is now the earliest example of Brando’s abilities in successfully embodying individuals who are emotionally and psychologically conflicted, as well as the desire to never let the actor outshine the character that is being played.

8. One-Eyed Jacks (1961)

Originally scripted by Peckinpah and later on slated to be directed by Kubrick, a certain touch of both individuals is prevalent here. Brando’s only directorial venture heralds the onset of the revisionist Western, years before Peckinpah would definitively give the subgenre its title. The moral bankruptcy of the once romanticized Old West is the central concern. Deceit is a defining characteristic of individuals here and the only path to peace is to give up the instincts that keep one alive and going. And Brando’s direction shows a distinct vision, far removed from the style of the dominant Westerns. There are frames of uncanny beauty and visual information used in keeping with its deceptive theme to build suspense.

Related to this Marlon Brando Film: The 15 Best Westerns of the 21st Century

From the moment he appears, Brando’s Kid is shown to not be one who enjoys violence like his comrades. His engagement with it is purely as a means of survival, in the world and his chosen way of life. As we see his determination build up, his steely gaze manifests an unflinching force of desire to avenge himself. Brando is not exactly sympathetic as an individual, because he distances himself from an emotional performance and makes the audience’s feelings for him strictly a product of his unfortunate circumstances. Even when he is with Louisa, there’s no drastic softening as among the two long interactions between them, in one he tricks her, and in the other, he sends her away. This laconic portrayal of a cowboy, resolute and businesslike, became a template for antiheroic cowboy characters that followed, like the ones played by Clint Eastwood.

7. The Missouri Breaks (1976)

Arthur Penn’s Western is a bizarre creation, one that oscillates between pure comedy and then moments of real threat and violence. It’s also a film that shouldn’t quite work, given how a large portion of the second act is divided into two storylines that seemingly have no connection with one another. Its cast includes the likes of Jack Nicholson and Harry Dean Stanton, playing rustlers planning a heist and possible revenge, which are thwarted by their intended victim’s employment of a peculiar regulator. Whether it is to be seen as secretly being a parody or if it’s a commentary on tropes of the genre can be argued about for ages. But what it certainly isn’t is predictable in any capacity.

Related to Marlon Brando: 10 Best Jack Nicholson Film Performances

Marlon Brando evidently enjoyed every minute of playing this role. His eccentric portrayal of an Irish-American regulator is among his most curious characters. He is flamboyant and extremely articulate, speaks in a tone and pitch that makes a character naturally guess that he’s a preacher. There’s a childlike sense of mischief about him yet he also fosters a thirst for immense violence. Interestingly, Penn uses a lot of shots from his perspective, as if to make him the character we ought to be rooting for. Because Brando portrays him with such a rakish flair, the audience might just consider it. From eating a plate full of raw, whole carrots to hinting at bestiality, here is a character portrayed with an unchained sense of self-consciousness, an attribute that spilled into real life with his antics on set.

6. Viva Zapata! (1952)

Kazan’s biopic depicts the life of Emiliano Zapata through a number of political upheavals, all of which include him in some capacity yet the central nature of his existence never changes. He’s a man always on the run, always struggling against the onset of complacency amongst the dominant regimes because unlike those in power and even some of his peers, he isn’t constrained by the thought of victory or satisfied with what is merely a better state of affairs than what was. What is so brilliantly depicted here is how men, through their actions and resolutions, transcend their physical presence and are elevated to the status of a legend. It won Brando the Best Actor award at the Cannes Film Festival.

Marlon Brando is clearly in tune with the constancy of Zapata’s status despite the change in the country’s fortunes. He has a steely-eyed determination from the moment he first appears amongst the peasants in Diaz’s court that never fades, even when he’s engaging in repartee with his to-be in-laws. This consistency is what assures our faith in him, in the fact that he is incapable of being corrupted, inspiring the viewer in the same way Zapata does his followers. It also is what lends credence to his insecurity, making that moment when he implores Josefa to teach him how to read in one night because he realizes the vehemence of that shortcoming and does not wish to waste any more time in equipping himself with it. And his sense of justice which he always assures is a telling precursor to his portrayal of Don Corleone.

5. The Fugitive Kind (1960)

Like all Tennessee Williams stories, its central concern is hopeless romanticism that tries its very best to assert itself in a world too harsh to accommodate it. Though among Sidney Lumet’s lesser-known films, it too is a work of infuriating power about socio-political prejudices that ruin lives and the American heart of darkness. Brando is set against the magnificent Anna Magnani who has the central role here as an aging woman trapped in a diabolical marriage, seeking freedom. This tale of provincial bigotry is among the most powerful works to have been released in the years that predated the New Hollywood movement.

Against Magnani’s portrayal that swings between optimism and despair, Brando becomes the anchor holding her in place. Unlike most of his previous roles, he rarely imposes himself during a scene. He’s quiet and resigned, perfectly attuned to the malaise of a young man belonging to a generation with seemingly no place in history. When he says, “I’m not tired. I’m fed up”, the words merely manifest what he had been depicting wordlessly till that point. The opening courtroom scene has vestiges of Terry Malloy. His insistence on changing himself in it is an excellent combination of determined intent underlined with self-doubt. A role easy to overlook because of its subdued nature and as one playing second fiddle to Magnani, it’s just as crucial a role in depicting Brando’s dedication to character, as it is a film showing the diversity of his body of work.

4. Désirée (1954)

One of many examples of Technicolor’s unparalleled ability in depicting period worlds. Scenes from it, some more directly like Napoleon’s coronation, and the others relatively less so are almost indistinguishable from the neoclassical paintings of Jacques-Louis David. It is a nifty portrayal of how worldly ambitions destroy domestic peace. Desiree’s life, despite her irreverence or probably because of it, has an illustrious quality that even the noblest courtiers at the time would not have dreamed of it. The film, in essence, being about her is an interesting exploration of the life of women at the time and what it meant to be headstrong as opposed to purely servile, to customs and luxuries, like Desiree’s sisters.

Brando keeps his chin lowered and never looks up at anyone, a technique that most effectively utilizes Napoleon’s towering arrogance which is not undermined by his notorious stature. He struts with a certain theatricality, as if every step he takes, every pose he strikes, is corresponding to paintings of Napoleon depicting him in all his glorious conceit. His voice sounds somewhat hoarse, exercising a lower pitch that reeks of an insecure sense of authority. The rare moment when he shouts magnifies the impertinence directed at him. And physically, nothing betrays what Brando looked like at the time. It is easily among his most insightful performances, one that mixes pomp and realism in equal measure, creating a most unique interpretation of Napoleon. This brilliance was recognized by Sir Laurence Olivier, who called it the best performance he had seen of the character.

3. The Godfather (1972)

Deemed ‘box-office poison’ by then, with his personal life torn, popping valium, and having resolved to never have anything to do with films, Brando was far from anywhere even interested in acting. For Paramount, the suggestion that an actor as volatile as him working on their film made them go ballistic. Yet Puzo had imagined him as Don Vito all along and Coppola was adamant on having him. So, Coppola faking epilepsy in front of Paramount’s president, the determination of Brando’s assistant, Alice Marchak to land him that very role, Brando’s own anger at the growing list of actors who were supposedly seen as his substitute for the role and a disguised screen test confirmed him as Don Vito Corleone. The rest is history.

Related to Marlon Brando: 10 Greatest Best Picture Oscar Winners of All Time

The beauty of Brando’s performance is his ingenuity as an actor. There is an unremarkable nature to how he looks and presents himself. He understands that Vito Corleone as a man has failed to outlive his own legend. He no longer commands the terror and authority he once did and has to reckon with the transience of his role. The emotional outbursts such as shaking Johnny Fontane up to be a man are the rare moments when he physically manifests his internal struggle to plan his succession. It all leads to the iconic scene with Al Pacino in the garden, almost a culmination of Brando’s career as the conversation so deftly shifts between joy on hearing about his grandson starting to read and regret at seeing the one son he wanted to spare the life of a mobster, becoming the heir to his crumbling empire.

2. On The Waterfront (1954)

Touted largely for Brando now, and rightly so, Kazan’s work is a revolutionary moment in the history of American cinema. Taking its cues from Italian neorealism and even French Poetic Realism, he made a film that was poetry and brutal reality in equal measure. Its depiction of blue-collar individuals, their lives, the fear and desperation that governs their world had a palpable quality to its characters that Hollywood’s interest in fantastic events and individuals as subjects could never bring to life prior to it. And what always goes unnoticed is the sheer brilliance of Rod Steiger’s performance.

Related to this Marlon Brando Film: 10 Criminally Underrated Best Picture Oscar Winners

There is nothing even closely resembling the majestic aura that was exuded by the likes of the biggest stars at the time like Wayne and Bogart, in Brando’s performance. From picking up Eva Marie Saint’s glove spontaneously or telling her, ‘Boy, what a fruitcake you are’ to his ingenious car scene or his last stand against terror, his work here is a delicate fabric of varied colors. It is conscience battling against itself, youth deprived of possibilities and ruined, regret at the prospect of a life denied, disappointment borne from trust, hope from love, and despair at the prospect of that life protracting. It is a performance of such paralyzing power that one will either be glued to Brando even when he’s showing his back or not notice anything because of the effortless ease with which he portrays the life of the likes of Terry Malloy.

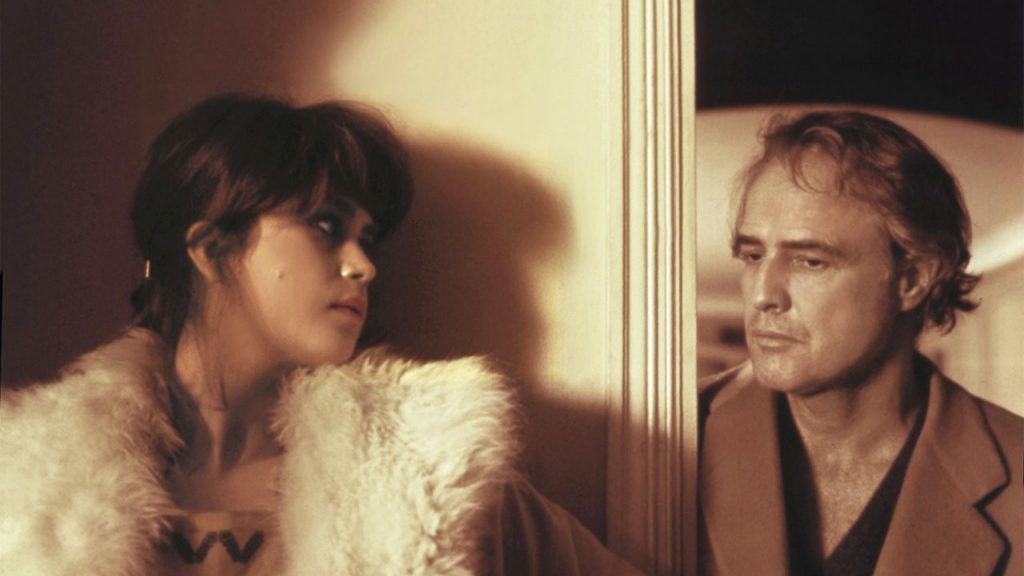

1. Last Tango In Paris (1972)

Bertolucci’s enigmatic tale about a curious se*ual relationship that is ignited between a middle-aged widower and a young girl is an exploration of identity, space, and memory, in a dreamlike, golden world. We see Marie Schneider in love with two individuals who as people and in their interest in her, couldn’t be more different. Here, like an apparition, the camera glides across rooms of large Parisian apartments and suburban villas, creating an aura of hypnotic beauty that hides within it, a terrible emotional violence. Like Paul Dano in ‘There Will Be Blood’, Marie Schneider’s ability to hold her own against Brando’s soaring performance should not go unmentioned.

Brando embodies the unpredictably mysterious nature of the film. Grieving his wife’s suicide, he shifts between outbursts of explosive rage and sudden outbreaks of tears. In the opening few minutes, he succinctly captures the essence of this character, ensuring that in the two hours that follow, nothing he does surprises us. It’s hard to tell whether this man is worth caring for or if he is a repulsive monster, leaving the audience in Schneider’s position, where one can only go by the present expression on his face and no amount of protest will reveal any more. In one moment, while chasing a john down the street at a prostitute’s behest, he beats the man up and then detaching himself from the violence, casually flicks his eyebrows, as if saying, ‘Well, that’s done now.’ This portrayal of debilitating grief that causes such anguish and ecstasy is one of the rawest performances ever captured on film.