Most of my writing about films begins with a cinema-related memory. A well of first experiences, I go back to those that will help trace what I feel about the topic at hand. What I feel about it will, in turn, inform what I have to say about it. When I first watched this. When I first heard of that. Subjective? Narcissistic? Write what you know? “What is most personal is most universal?” A fitting point to start a conversation about Nair’s filmography.

This article has been due for a while. In the time since I began writing it, I moved cities, hit a personal and professional milestone, living and marinated in the definitive themes of Nair’s best work: the near-constant homesickness of a vagabond self longing to belong in this complicated world we have custom-built for ourselves. An opportune moment to honour the “producer of the candidate”, now the mayor of NYC, and king of our feeds, came and went. Zohran Mamdani is an eclectic mix of charisma, clarity, social consciousness, and cultural roots that stretch all the way to East Africa and the Global South. Dare I say he is Nair’s filmography personified?

By the time I got around to finishing it, I was back home, albeit for a short break, to the starkness of a shifting dynamic where one suddenly finds themselves in the driving seat, scolding their fathers or sighing at their mother’s screen time. These are the moments where Nair’s most loved work resides—seemingly simple, heavy with life. When I first heard of Mira Nair, it was through the closing credits of “The Namesake” (2006). A tale of clashing dissonances, of an immigrant father away from homeland (Ashok Ganguly played by Irrfan Khan) and the angsty son struggling to belong in the dreamland (Gogol played by Kal Penn).

I had been introduced to the film as one of the best diaspora films out there. It was at a time when I didn’t bother with who directed what, and let the star cast be the determinant of what I watched. Nair was one of the first who made me stop in this ignorant track and pay attention to who had managed to delicately capture a lonesome Irrfan Khan in a career-defining performance. The ghost of Ashok would come back to liven Saajan Fernandes of Ritesh Batra’s “The Lunchbox” (2013). A once-in-a-generation actor, introduced to the world first in a scene of her debut feature, “Salaam Bombay!” (1988).

The story goes that she spotted him at the National School of Drama when researching for the film, had him on board as they workshopped the film into existence, but had to let him go. Despite his striking talent already evident at 18, he was too tall and fit to be a leader to the impoverished street children who formed the stars and heart of the film. It was only 20 years later that the duo got together again, but I digress. This is a retrospective, reflecting on the best of Nair’s filmography, inviting you, who may have heard of Zohran first and Nair later, into a conversation about what I consider a ‘must-watch’ from her filmography.

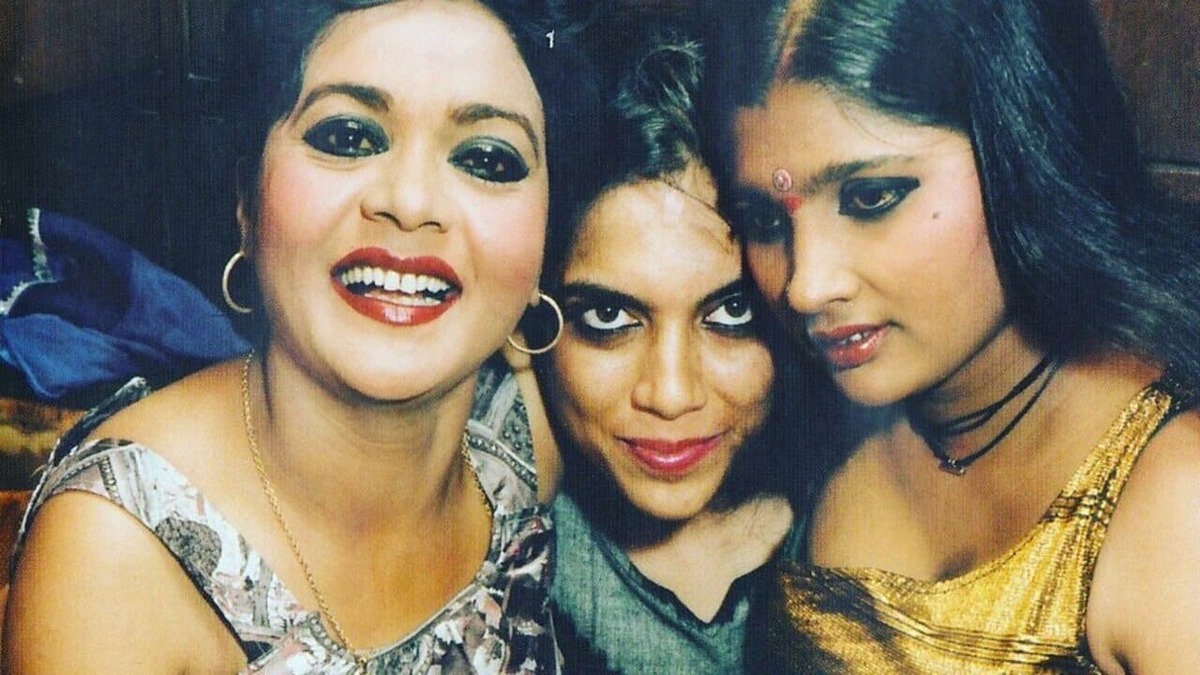

5. India Cabaret (1985)

Mira Nair started her career with documentaries, interested in establishing the personhood of those her questions inquire about, and the camera captures. Her second film, “India Cabaret,” takes us inside the bars of Bombay and the hypocrisies of a society that sanctifies the “good” woman while consuming the “bad” one.

Of these bad women, self-admittedly baddest is Rekha, a fiercely feminist dancer who’s cracked the code: “a woman must keep appearances of submission to whatever is expected of her in and outside the bar while truly only doing what she really wants.” Easier said than done, but at the end of this hour-long film, where Nair takes us through the hells, homes, and hearts of those on the fringes, Rekha manages to retire early while having two suitors waiting and property to her name to have her back.

From these early films onwards, what strikes most is that to Nair’s camera her subjects are not specimens for the viewer’s curiosity, nor props for her politics. They are people in their own right—messy, contradictory, alive—who grant us access to their lives not because of a filmmaker’s authority, but because of her trust. This candour is not accidental. It is the result of work: of listening, of spending time, of allowing the frame to be shaped by the person within it rather than the other way around. Nair says she chose cinema because it is a collaborative medium. Watch the film to see how she lives up to this belief.

4. Mississippi Masala (1991)

In the early 70s, during Idi Amin’s dictatorial reign, Asians were expelled from Uganda, the land many Indian immigrants have hailed as home. Jay’s (Roshan Seth) desperate pleas, reiterating the same to his childhood friend Okelo, are met with “Africa is for Africans, Black Africans,” a statement that breaks his heart into more pieces than the sudden political shifts in his home country.

This hurt turns into a heritage of hate that his daughter Mina (Sarita Choudhury) is expected to carry even when they are miles and years away in Mississippi, America—the land of dreams and Indian-owned motel chains. Instead, she finds herself falling in love with Demetrius Williams (Denzel Washington), an African American man, owner of a carpet-cleaning business.

Before anything else, the film stands out for the chemistry between Washington and debutante Choudhury. They make you root for them just by how good they are together. She is fiery, effortlessly sensual. He is calm, grounded, and charming. It begins with an accidental meet-cute (literally) of opposite personalities, an essential element of a romcom, and the aftermath is a nuanced exploration of interracial relationships, elevating it to a drama reflective of Nair’s sensibilities as a filmmaker.

It is best to observe this film as a meeting point and confrontation of cultures—of Jay with his misplaced hate and of the filmmaking conventions that shape Nair—living up to the use of ‘masala’ in its title. The visuality lends itself to the softness of indie films and the dramatics, on occasion, to Bollywood. In a tense scene embodying the plight and anxiety of immigrants expelled from their homes, as the family flees in a bus, a drenched Sharmila Tagore, playing Mina’s mother, is interrogated at gunpoint.

The dictator’s police rob her of a music player that hums Mera Joota Hai Japani and her mangalsutra. In contrast, years later, on a trip to the beach with Demetrius, Mina finds herself in the soft light of the setting sun and the freeing breeze of having gotten away. As worlds of different generations and cultures clash, each must make a choice that serves them best—of choosing love and forgiveness.

Related Read: 10 Best Denzel Washington Movie Performances

3. The Namesake (2006)

The lore is that when two very different directorial pathways diverged for Nair, who stood with offers to direct the third Harry Potter film, “The Prisoner of Azkaban,” and “The Namesake,” it was Zohran who pushed her to pick the latter. If that doesn’t convince you the man is capable of leading NY, I don’t know what will. Anyone could tell a Harry Potter story, but only Nair could helm the adaptation of Jhumpa Lahiri’s celebrated book in the way she did, he reasoned. Thank heavens he did. What resulted is a delicate study of how names and homelands make us, and the need for belonging that defines us.

If there are two things evident in Nair’s filmography, the first is that she loves creating wedding sequences. The second is that she has an eye for casting people and directing them such that it results in undeniable chemistry. The Namesake’s exposition is a prime example of this. When Ashoke Ganguli (Irrfan Khan), having survived a train accident and built a dream in the USA that was born on that very same train, comes to see Ashima (Tabu), he attempts to catch a glimpse of her face, but in early arranged marriage meetings, the prospective bride and groom must only stare at the floor.

Perhaps it is only on the wedding day that he gets a chance to look at her and finally win her heart in a lonely, cold country. Like “Mississippi Masala,” watch this film for the lead pair—the incredible pairing of Irrfan Khan and Tabu as young parents building a home away from their homeland. Years later, she reveals to him that it was his shoes that won her over before anything else.

The shoes Ashoke has walked through life in will not fit his son, Gogol—aka Nikhil, aka Nick (Kal Penn)—until life comes full circle and he must finally wear them. In the middle of the struggles of immigrant parents and Gogol coming to terms with his name—identity by extension—is a universal father–son story where each stands misunderstood.

Also Read: 15 Best Irrfan Khan Movie Performances

2. Monsoon Wedding (2001)

Aditi Verma (Vasundhara Das) is to marry the Indian-American Hemant Rai (Parvin Dabbas). An elephant sits in the middle of this arranged setup. Lalit Verma, the best of all screen fathers played by Naseeruddin Shah, is the patriarch responsible for making it all happen. He runs around the house, ensuring the tent is set up, flowers are fresh, and all is set, paying for it with cash and worries. Pimmi Verma (Lillette Dubey), the mother, gets anxious and smokes it away as her daughter inches closer to becoming a bride.

Imagine the bunch that would gather at a quintessential Indian wedding—an unabashedly outspoken aunt (Kamini Khanna), a life-of-the-party uncle (Kulbhushan Kharbanda), an older cousin reduced to her unmarried status (Shefali Shah), a tween still unaware that your body, preferences and performance must align with gender norms, alternatively a tween happy following his heart (Ishaan Nair), a distant relative’s flirtatious son (Randeep Hooda), a cousin venturing into young love (Neha Dubey), a dreamy-eyed house-help (Tillotama Shome), a street-smart wedding planner (Vijay Raaz), that one creepy uncle (Rajat Kapoor), his wife who turns a blind eye to his perversity—you know it, this is a version of all our families ‘exactly and approximately’.

This phrase, uttered by a show-stealing Vijay Raaz’s PK Dubey as he tells Lalit the cost of putting up a waterproof tent is ‘2 lakhs “exactly and approximately”’, best describes what this film manages to capture—the exact bittersweetness of a family wedding and the approximate subjectivity of that experience. In doing so, the film feels particularly intimate. In a poignant scene, as the parents look over their sleeping daughter, they exhale how fast time has gone by.

In another, the house-help, secretly trying on the bride’s jewellery, looks longingly at her reflection while her lover gazes at her through the window. We see the casually ostracised unmarried cousin Ria’s body stiffening when her abuser’s eyes fall on her. In my favourite scene, when the abuser is named, a disabling helplessness takes over because such things are only hushed away. Watching “Monsoon Wedding” is to peer into familiarity—comforting and discomforting both—an experience crafted by Nair with such finesse that it won the Golden Lion at the Venice International Film Festival, along with a nomination at the Golden Globes and a screening at Cannes.

1. Salaam Bombay! (1988)

A couple of years back, at the Hollywood Reporter Roundtable, when Greta Gerwig was asked ‘What is cinema?’, her simple, succinct response was ‘you know it when you see it’, a definition I kept going back to while rewatching “Salaam Bombay!”. Not just because the film stands as a specimen of this definition, though it does. Two wins at Cannes (Caméra d’Or and Audience Award) are proof enough. But because Nair has an exemplary eye for what can become cinema and the skill to turn it into cinema. This may be a stretch for all her filmography, but her early work, especially the results of her collaboration with Sooni Taraporewala, holds up to this claim.

“Salaam Bombay!” remains her finest achievement: a scenes-from-the-street, neo-realist feature that follows the lives of homeless children in Bombay. Set in spaces only transitory or heard of to the majority who would eventually watch this film—the railway platforms, meat shops, brothels, and chawls of Bombay—she takes the viewer into the lives of prevalent but unseen children of India, ones you don’t know or think of beyond mere seconds of interaction at a traffic signal.

These encounters are almost always a sales pitch for a service, a newspaper you don’t need, toys you will discard moments after purchase, or snacks you don’t prefer. The bottom line is that they are in need of money for survival. What it demands, costs, and erodes is what Nair insists we confront.

Taraporewala and Nair keenly observe and empathetically curate a portrait of life on the margins as lived by Krishna, a pre-teen arsonist thrown out of his house on a mission to earn 500 rupees so he can go back home and repay the damage he caused; Manju, a little girl born and raised in the city’s red-light area; Sola Saal, a trafficked teen; and Chillum, a drug peddler and addict. Throughout their intertwining journeys, struggles, and stolen moments of joy, the film gives a face to the many faceless children of the streets.

Beyond its merit, the film now also serves as a way to meet Irrfan Khan, Nana Patekar, and Raghubir Yadav as young performers starting in their artistic journeys, something that further strengthens the case—Nair has an eye for what makes great cinema. The film stands at an intersection of documentary and fiction, with trained and non-actors.

The observer effect, when the mere presence of a camera turns reality into a stage, and those on it are aware of being seen, inevitably becomes the biggest challenge of the genre, followed by access to locations and ethics. Nair, despite this being her debut work, has a masterful hold on all three. At no point is reality forced or fiction stretched, nor is location exoticised or suffering turned into spectacle. It is this balance that earns the film the revered pedestal it deserves even today.