Casa Grande (2014) – A Non-Traditional Bildungsroman About Class, Color, and Comfort: Segregation has been long since banned in most American countries. However, its roots go deep enough to re-emerge and rear their distasteful head from time to time. Progress is always measured in terms of the wealth accumulated by the ruling elite. The underlying inequalities which dictate the opportunities and the results are often ignored. The relentless struggle for survival involves all the parties in a ruthless game of snatching the bread. When it all starts going downhill, many are left to pick up the pieces from the scrambled mess and put them together. So, they can reflect upon the mechanisms which led to these unwanted developments if they are sensible or empathetic enough to make time for this abject rumination.

“Casa Grande” is set in a plush neighborhood of Rio De Janeiro. Jean, the son of an upper-middle-class hedge fund manager, is on the cusp of adulthood. He indulges in frivolities typical of his age group – flirting with girls, fighting with boys, partying. But most notably, he repeatedly fails to seduce his housekeeper, sneaking into her bedroom for some midnight action and receiving none. The father, Hugo, is riddled with debt and tries to hide it from their children with the help of his wife, Sonia. Slowly interpersonal resentments start to unravel as Jean gets involved with a mixed-race girl from a lower economic stratum, and the family is on the verge of selling their house.

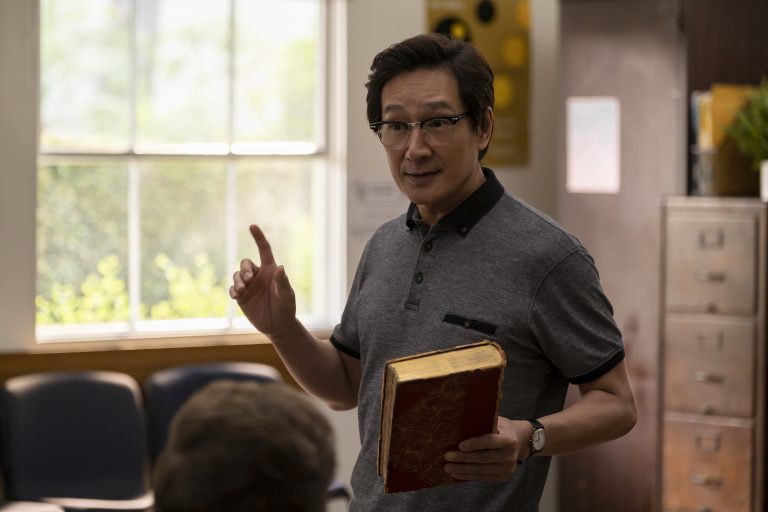

His journey does not follow the typical charted course of a bildungsroman. The film is structured in the style of vignettes, an episodic format recording various events from the life of Jean, which deliver certain statements on the present condition of race, class, and gender in Brazil. He goes to a private school with one or two African American students in his class. When his parents find themselves in a tough spot to prevent bankruptcy, their fire their longtime African-American driver without any notice period or severance package. The indispensability of working-class people is especially visible in a marvelous scene where Hugo fights with a van driver on the petty issue of parking in the middle of the road. The inconvenience driver faces is brushed off by the father as an unnecessary ruckus. It is an unabashedly arrogant display of unwarranted class dominance where he can humiliate the driver and easily get away with it. Or comment on the desirability of black women as if it means nothing to him as a human being. So, it is not surprising when the ax falls on the family’s fortune, these people working under them have to bear the brunt.

Meanwhile, Jean embarks on his own journey of newly-discovered manhood. He is mostly ignorant of all the important matters that concern societal well-being, too busy floating around in his shiny privileged bubble. It comes as a huge shocker to him that his driver Severino has been sent on a “vacation”. Now, he will have to commute by bus – a big deal for the family. They bombard him with warnings about mugging and the crime rate in Rio, advising him to move with caution. The restrictive impositions on his movement curtail his freedom and agitate him further. He is desperately seeking an outlet for his bottled-up feelings, roaming from one botched attempt to another. Soon, his obliviousness to his country’s political scenario lands him in trouble.

The seemingly innocuous romance with Luiza is laden with acute social commentary. From her retort to his assumption (that she belonged to Favela – the lower-priced African American community housing area) that it was made based on the color of her skin. To the heated argument with his father and his broker friend over the reservation quota for minority groups, her self-assurance is indomitable and somewhat scary to Jean, who just keeps molding his ideas to make an impression on her. Most of his opinions are half-baked or influenced by his parents, to his annoyance. Being called out for his father’s prodigal debts enrages him, appending his already wounded self-esteem. Consequently, these mounting tensions make him unable to get an erection while making out with his girlfriend. This self-doubt and frustration make him question her virginity, an imprudent query that impels her to leave. His parents’ secrecy, and his own lack of awareness of the norms that govern his life, directly or indirectly, have completed their shelf-life. It has reached a tipping point where all his reservations about his life and family are about to spill over.

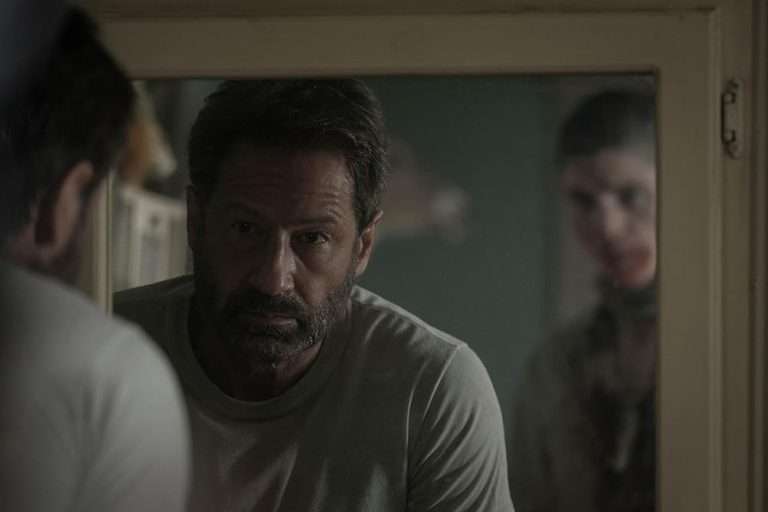

So, he runs away from his home after having an honest confrontation with his father, which soon turns physical. Fed up with his lies and betrayal, he travels to the place where he had spotted Severino during one of the bus rides. There he hugs him tightly. The only man with whom he shared a real connection. Rita, her housekeeper, is also present there. She was fired by her mother when Sonia found naked photographs of Rita under her bed. Though she claimed it was none from the family (information which is never confirmed till the end if she is lying or telling the truth), Sonia is livid but calmly contains it to focus on finding the culprit. But, the mystery evades her, and she is left to believe her words or keep hanging in the doldrums. Obviously, she chooses the former to maintain her peace of mind in an increasingly perilous situation.

The movie captures the contrast between the different neighborhoods, segregated by class distinctions, through appropriate imagery. When Jean enters Severino’s home, we get the sense that he has come into a different world altogether. His journey is complete not by ascending the stairs of prosperity. But by plunging into the netherworld of his conceit which could choke him asunder. Like Odysseus, he is stranded in the sea of marginalization and poverty, seeing it through his eyes for the first time in his life. But unlike in the epic, his actions have no moral message. His family is bankrupt, and sooner or later, he will succumb to the same affliction, which has corrupted more than half of his city’s population. But for now, he is content with his actions by reconciling with Severino and Rita. He has seen the consequences of his father’s recklessness which affected his most important relationships. So, he revels in the newfound freedom from the stifling, oppressive claustrophobia of his home. They wait for him with anxiety, nearly falling into a kidnapping scam. But, Jean is heedless of their worries.

Rita, who earlier rejected his advances, took pleasure in his suffering, and called him out for not being “man” enough, has now embraced him with open arms. The moment his hormone-addled brain has been pining for so long has finally arrived. And this time, he is able to go through with it, unlike the last time with his girlfriend. There is no baggage hanging on his shoulders to study economics or law with his private school credentials. Those shackles have been shunned, and he has regained his confidence through this rendezvous with Rita. His past, present, and future exist in this new bubble. There is no major change in his nature like in other coming-of-age stories. But there is considerable improvement in his outlook toward life and exposure to the dark side of the moon. He is now fully aware of his privilege and the cost of attaining it. For the moment, he exists somewhere between the two worlds, belonging to neither. But his presence seems justified and significant to him, like the sunlight coming in through the window where he sits. Waiting for the next step or perhaps settling himself in this space- of rejoice, relief and rapture.