The very name ‘Ingmar Bergman’ is enough to stir up a thousand images in the minds of many cinephiles. These images will be in black-and-white, of women suffering in psychological torment, and contain the deep-focus cinematography of Sven Nykvist or the contoured face of Liv Ullmann. His films received unanimous acclaim during his lifetime, but the evolving tides of cinema criticism have perhaps signaled a shift away from Bergman worship in recent years. However, as we attempt to reshape a more inclusive canon of world cinema, we shouldn’t forget about the greats whose legacy defined so much of 20th-century film. Bergman’s stark, often bleak, meditations on the human condition represent some of the most gripping dramas ever put to a film and the most empathetic, arresting portrayal of femininity a man has put to celluloid.

Another drawback to Bergman for some is the sheer size of his body of work. Whilst a film such as Fanny and Alexander may be his most fulfilling work, is it a better or worse starting point than his classics from the 1950s? When should you get into Persona, that infamously unorthodox puzzle box of a movie? What hidden classics are lurking further down his page of credits that experiment with comedy and fantasy and are worth a shot? Many questions are to be answered, and this article will offer a beginner’s approach to the world of Bergman, taking you by the hand through one of the most accomplished catalogs in cinema history.

Where To Start With Ingmar Bergman

In 1957, Ingmar Bergman made two masterpieces that beautifully surmise the overarching themes of his life’s work: The Seventh Seal and Wild Strawberries. Both are essentially concerned with mortality but take very different approaches to reach similar conclusions.

The Seventh Seal is framed around one of cinema’s most iconic scenes, in which Max von Sydow’s knight challenges death incarnate to a game of chess to determine his fate. It’s an oft-parodied sequence that renders life’s sense of challenge and coincidence in an unforgettable metaphor. It is played with a balance of subtlety and absurdity by Von Sydow and Bengt Ekerot, who is chillingly deadpan as death himself.

Wild Strawberries’ format has been rendered equally familiar by imitation and iconography since the film’s release. It follows Professor Isak Borg (played by Victor Sjöstrom, an acclaimed director in his own right) as he travels to receive an honorary degree honoring his life’s work. But rather than reflect on his professional accomplishments, this sobering road trip movie is a meditation on the failings of his personal life, how his grouchy demeanor and restless pursuit of reason have distanced him from those around him. Bergman pushes the envelope here with his layered approach to storytelling and some atypical formal innovation, such as scenes where we see Borg interact with characters within his memories, though, of course, he is unable to change his previous mistakes. Only through redemption and forgiveness can mistakes be amended, perhaps a positive message to conclude this cerebral reflection on mortality.

Delving in…

After sinking your teeth into Bergman’s leanest and most efficient mission statements, it’s probably time for Persona. But don’t be daunted. Despite its reputation, Persona, like all Bergman films, is an innately pleasurable viewing experience for the visual flare and skillful performances alone. It’s easy to forget how engrossing and visceral the emotions wrought by Bibi Andersson and Liv Ullmann are. In its own strange way, Persona is deeply romantic, loopy, and vivid in its eroticism and exploration of feminine duality. Almost 60 years on, there’s still nothing quite like it, a towering achievement of arthouse cinema, which Bergman himself never quite managed to top.

Ullmann was perhaps Bergman’s foremost muse among the many talented thespians he worked with. Scenes from a Marriage pairs her with the equally gifted Erland Josephson in a subtly heartbreaking depiction of failing matrimony. Available as both an expansive miniseries or a taut 3-hour movie and remade with middling results by HBO three years ago, in whatever medium one engages with the project, its power cannot be denied. It’s as if Bergman drew the outline for the relationship, and the Ullmann-Josephson pairing filled it in with a million little details of facial arrangement and blocking. There’s little in the way of judgment from the camera itself. Instead, the director allows you to be a patient observer of problems that are deeply universal.

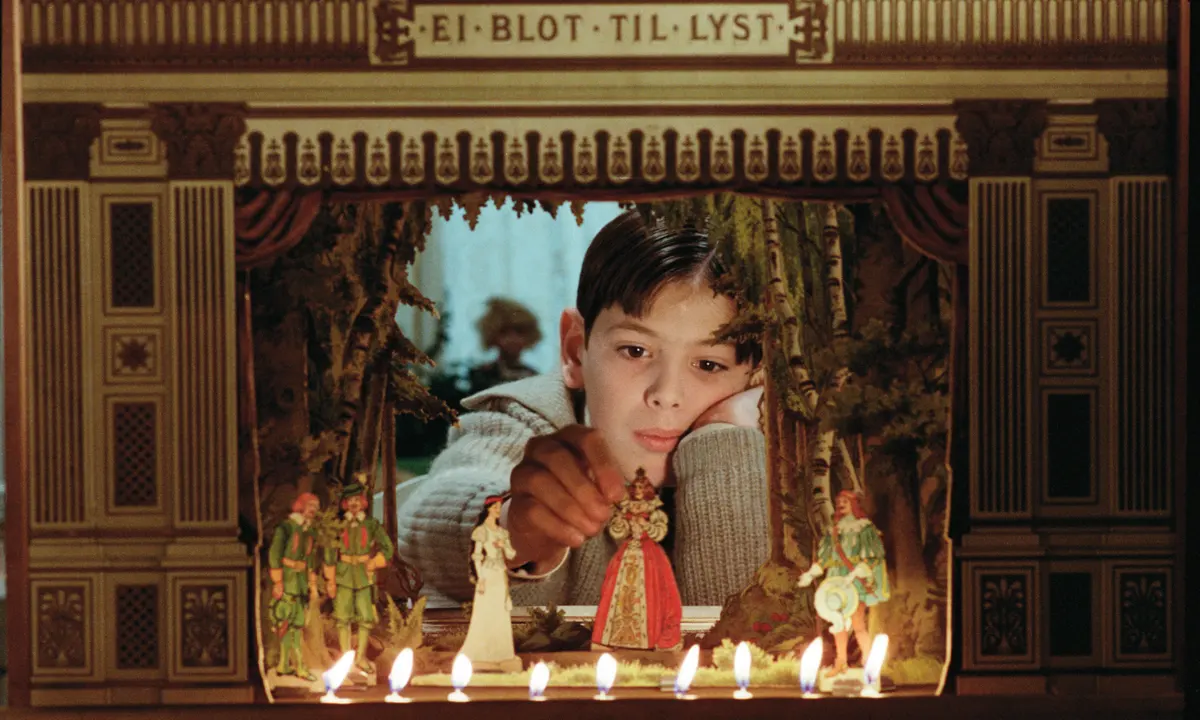

The family unit is also under scrutiny in Fanny and Alexander, Bergman’s last big crossover success and his de facto swan song from a medium he did so much to shape. This time, the Swede dips into his own upbringing, delivering a semi-autobiographical script that aches with the growing pains of troubled adolescence. Anchored by two of the best child performances ever committed to celluloid as the titular siblings, Fanny and Alexander operate best as a think piece on institutions – the church, the family, the patriarchy – and how they shape human relations and thought.

Fanny and Alexander are children who are remarkably malleable to their environment, and as their loving father makes way for their domineering stepfather, they undergo changes both big and small. One should resist an overly nihilistic reading of Bergman’s oeuvre, though. After all, just observing his command over image and human emotion should be enough to reaffirm anybody’s trust in the world.

For the diehards…

If you’ve made it this far and watched each of those four films, you’re probably in the mood for something lighter. Rest assured, because Bergman has made a surprising number of comedies, which flipped his usual wheelhouse of themes into something farcical rather than tragic. Smiles of a Summer Night is seen as essential by some, inspiring both a Woody Allen remake and a Stephen Sondheim musical, but for me, A Lesson in Love is the funniest film he ever made. Set mainly on a train journey to Copenhagen, the film mirrors the screwball comedies of Howard Hawks in its intelligent dialogue and indelible charm. It’s a fun ride, even for those usually turned off by the director’s overbearing nihilism.

Also worth a look is the criminally underrated The Touch, an American co-production that initiated a rare contact with American movie stardom for Bergman. Starring alongside Bibi Andersson and Max von Sydow is Elliott Gould as, a holocaust survivor who enters an extramarital affair fraught with sexual frustration. A critical and commercial failure upon its release, The Touch’s reception seems inconceivable now in a modern cinematic climate relatively bereft of such engaging and nuanced portrayals of adult themes. Bergman would retreat back to Sweden for the following years’ Cries and Whispers, though, so something good came of it in the end.

Best of the rest…

It would be neglectful of me not to mention some of the other brilliant films in Bergman’s back catalog. Because of his reputation in his lifetime, most of Bergman’s films are already available in crisp HD copies in physical boxsets and on artier streaming services. I once binged several of his early works from the 1940s, and Prison was the most visually exciting of the bunch, each shot overspilling with the creative spirit. It’s also one of Bergman’s most direct dissertations on the film industry itself, following a film director and his fractious relationships with his wife, friend, a young sex worker, and a former student. It also allows for a spotlight on Eva Henning, the young blonde bombshell who would provide his muse for both Prison and its (admittedly less satisfying) successor, Thirst, setting a precedent for Ullmann and the Anderssons in years to come.

For something more challenging, check out Bergman’s thematic trilogy of the early 1960s when he was really hitting his stride as the preeminent chronicler of spiritual ennui. Through a Glass Darkly is unapologetically theatrical and austere in presentation, though impossible to disregard on the strength of the performances alone. Winter Light is a more transparent take on religion, depicting a priest in a crisis of faith in both his wife (Ingrid Thulin) and his Church. The Silence is my personal favorite, an involving drama whose themes of feminine duality foreshadow the genius of Persona. Like that film, The Silence has encouraged much scholarly debate – a popular theory posits the two characters as sides of the same woman – and rewards repeated viewing.

I hinted at the brilliance of Cries and Whispers earlier, but it warrants further praise before I close this article out. Bergman made plenty of films in color after 1970, but this is the only truly colorful one, a distinctive red hue overwhelming all aspects of production design and costuming. Like all of Bergman’s best, it’s also a bracing actor showcase, this time for Harriet Andersson, Thulin, and Erland Josephson, all of whom express grief in subtle but expressive ways. It undoubtedly stands among cinema’s foremost portrayals of sisterly love, directly influencing the work of the aforementioned Bergman disciple Woody Allen.

Of course, hundreds more words could be written on each of these films, but in giving a broad overview of Bergman’s work, I hope I’ve been able to entice you to explore his extremely rewarding body of work. At the height of his powers, he was generously prolific, meaning it’ll take time to get through all of his films, but patience is a virtue in regards to Bergman, who often let his films unfold slowly, unraveling their genius with each meticulously blocked scene and acutely observed performance. In terms of consistency, thematic range, and formal abilities, it’s hard to beat Bergman, and I wish you luck on your journey into his world.