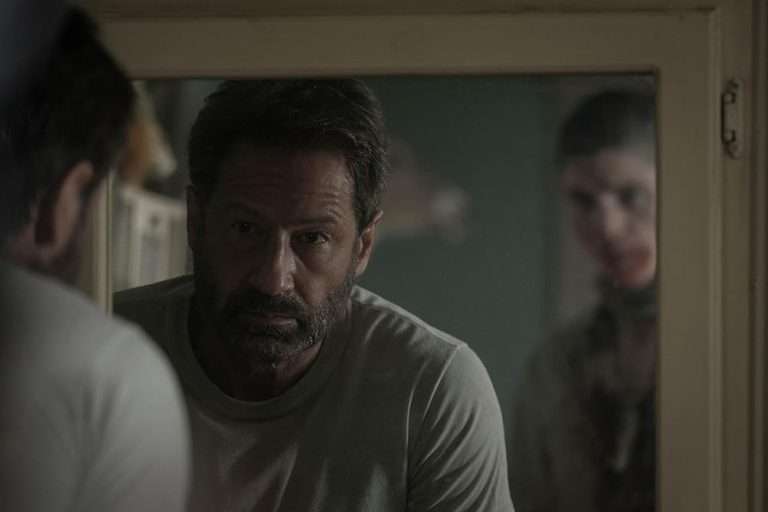

Jai Bhim (2021) Prime Video Review: At a crucial junction in the film as the second act concludes and the third act is about to set in, Suriya is confronted by the people his character is fighting for upon a tragic discovery. The tragedy is overwhelming so as an audience you are driven into sorrow but the gaze, once locked at Suriya, doesn’t correct its course to focus on the confronter and moves with Suriya, who then gradually captures the entire frame. The angle of the shot goes down as Suriya walks as tall as the mountain in his background.

A shot doesn’t deserve to get scrutinized to its every single frame but this particular shot here is a representative of the sample of shots dominating this film, different in terms of palettes and otherwise aesthetics but homogenous in terms of the effect they have on a viewer. Jai Bhim (Prime Video) is another case of ignorant sympathy manifested into a film that subconsciously reinforces the liberal oppressor’s idea of justice for and emancipation of the marginalized.

Related to Jai Bhim (Prime Video): Ram Ke Naam (1992) Review: A Cop Out Take on the 1992 Riots

To promote this film as a story of a lawyer’s struggle to get justice for a tribal woman would be disingenuous even if it is true in its rudimentary form. It should be marketed strictly as a biopic of Justice K Chandru. In the first case, the film becomes one ridden with a savior complex. In the second case, it becomes a film about a real-life savior who deserves to be known to the world. But it continues to function as a film about Suriya in the role of emancipator.

The opening sequence delves right into the daily routine and banter of Irula people with a jovial celebratory tone that attempts too hard to make a point that the onscreen events and gestures are “supposed” to be treated normally. It is a way of life so it is normal from a sociocultural outlook. But rather than treating it as normal, the film “portrays” it as normal, and this conceived normality immediately infantilizes its subjects. You understand them from an impersonal space. A higher vertical is assumed from which you look down upon them with pity and a sense of kindness which only arises when power hierarchy becomes overt and disturbs your illusion of equality as a basic human right. Once the subjects are infantilized, they operate within rigid archetypical character boundaries.

Your sense of pity keeps on escalating and the film manipulates you to submit to the innocence of the victims, which however true, is lethal to the nuance they have as humans. One can say that the hero is a righteous truth-seeking man without materialistic aspirations whereas his subjects are a forever-crying lot of desperate people without resources and access. This, again, is nonproblematic as an absolute fact but in cinema, every piece of information exists audiovisually, and hence for example, if I write that Irular people are desolate and downtrodden while the lawyer is affluent, there is no invisibilization of either party but if I show it onscreen in its diluted form, the lawyer’s heroism snatches away the focus from the downtrodden subjects and strips them of their complex humanity.

To elucidate my argument further, I would quote Congress leader C. Rajagopalachari during the Vaikom Movement on 27th July 1924. As people from marginalized castes agitated to use the public roads to the Mahadeva temple in Vaikom, tension rose in the dominant caste groups. Rajgopalachari traveled and addressed the privileged castes quoting “Let not the people of Vykom or any other place fear that Mahatmaji wants caste abolished. Mahatmaji does not want the caste system abolished but holds that untouchability should be abolished … Mahatmaji does not want you to dine with Thiyas or Pulayas. What he wants is that we must be prepared to touch or go near other human beings as you go near a cow or a horse … Mahatmaji wants you to look upon so-called untouchables as you do at the cow and the dog and other harmless creatures.”

The oppressor castes have had the privilege of ignorance that has also accorded them with the liberty to look down upon the oppressed castes with a parental or master’s gaze. The easiest way to invoke sympathy intrinsically is to look at the subjects as harmless, innocent, and powerless creatures which simple attitudes, and zero agency. When sympathy is invoked in this manner, i.e. by infantilizing them or by comparing them with harmless animals, the liberal oppressor is enabled to appropriate their agency for his self-interest in the veil of altruism.

I don’t mean to say that this is what Justice Chandru did. But unfortunately, the film does it when it chooses to be built around characters that are carved out from stencil. The police here are personified evil. The righteous and honest officer is otherized. The tribals are victims. The hero is the savior. The prosecution is vile or stupid with comic mannerisms. And the film is a canvas of torture sequences and foul play that are less concerned with sketching an ugly reality, much like Visaranai, and are more concerned about manipulating the audience into a mix of rage and sadness while also serving their voyeuristic gaze.

The problem lies in the fact that a story about systematic violence against tribals and a man’s landmark victory against the state must cause some form of disillusionment for the privileged caste-class groups but rather, all it manages to do is to evoke ephemeral anger for 3 antagonists and a surge of pity and sympathy for the 4 victims, strictly within the film’s universe. In the end, Jai Bhim is reduced to a culmination of triggers to shudder its audience from their comfortable position but without instigating any form of introspection in them.

Also Read: Article 15 (2019) Netflix Review: An Outsider’s Outburst

The sole merit of the film is its edit that attempts to create a screenplay reminiscent of Otto Preminger’s Anatomy of a Murder (1959) which keeps the thrilling tone intact and the murder investigation intriguing. The camera and lighting majorly serve the protagonist’s iconization and the antagonist’s diabolization. Jai Bhim deserves credit for bringing an important story to the mainstream but it also warrants a discourse on its outdated aesthetics in the light of the emergence of filmmakers such as Mari Selvaraj and Pa Ranjith who have managed to bring the account of the oppressed in a manner that not only feels personal but also dignified. Their angst is channelized rightfully into their narratives while their cultural aesthetics represent an assertion of identity and not a tool to render shock to viewers.

Stories cannot be monopolized in the hands of a few. Nor can they be reserved. However, only experiences can determine how those stories will be executed in a film. The only way in which this experience gap can be bridged is to take an anthropological route to retain the complexity of events, legal or political, and present them as they occurred. All the agents such as actors, contributors, researchers, technicians, etc. function around the stories in the aforementioned case. Jai Bhim is an unfortunate case, among many, in which the story is morphed around its star to increase the weight of his filmography.

![Head-On [2004]: About Broken Relationships & Emancipation of Masculinity](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Head-on-2004-768x432.jpg)