As Joaquin phoenix excelled the role of the not so unpopular masked vigilante, Joker is once again the hot topic of discussions among comic book fanatics, cinema goers and surprisingly the Army and other considerate people as well.

The concern of the US army regarding the film can be termed as a bit exaggerated, but there’s no overstatement in praising the cinematic brilliance and powerful performances which make the Todd Phillips flick a memorable one. But as it is said – “No good art is ever apolitical”, the story always maintains social imbalance at its heart.

This leads us to the main question. Western cinema, or any other art form of that matter has always been able to show at the same time sensitivity and apathy towards the country’s political scenario. Why haven’t we?

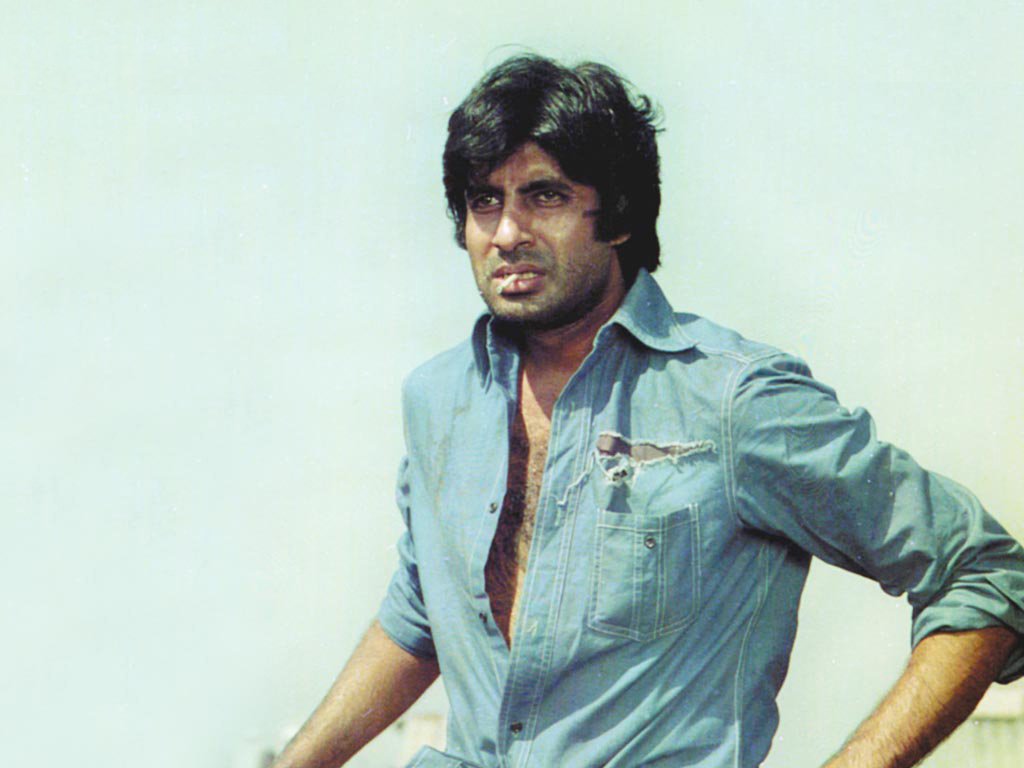

We as a country have never been able to do that. Our mainstream cinema has never been that political, although we came close. Mr Bachchan’s profound roles depicting the suppressed aspirations of the so called lower class laborer led to the advent of angry young man in contemporary cinema.

This labourer and Arthur Fleck more or less have the same story – a terminally ill mother, estranged from father, step brother living a lavish life, upper class society laughing at him – and that too without even having a mental illness. The scene where Arthur confronts Thomas Wayne in his huge mansion and Wayne rejects his claims declaring his mother a crazy woman, we as an Indian audience can feel the sense of an eerie Deja Vu. The storyline/theme of Joker feels similar to that of Zanjeer (1973), Trishul (1978) until of course the point where the recipe of a ‘psychological thriller’ is injected into the film.

When you see it in a global context, the angry young men movement was started by British playwrights and novelists in 50s to present their critical views about the society. It started gaining pace in Indian cinema when Congress’s policies started to take an anti-socialist turn in early 70s. Lacs of men were coerced into sterilization. So Bachchan’s lines like, “Are ye jeena bhi koi jeena hai lallu” or “Main aaj bhi phenke hue paise nahi uthata” were not just dialogues; they actually took a subtle stand against government’s policy – something which is rare in today’s cinema.

I wonder why the angry young man never went crazy like Joker – is it because he always had a ‘not-so- important-to-the-story’ love interest to look after him, or just because we as an audience were never ready for the paradigmatic shift in our hero’s intentions; or is it because the filmmaker was afraid – much like the recent times.

Despite all the criticisms we make today, nearly all of Amitabh’s movies centered around the Angry Young Man were huge box office successes. One could argue that this is exactly the kind of attitude we have as a country towards “cinema” or any other type of “art” for that matter, even today.

Instead of viewing films as a medium of expression of the filmmaker’s thoughts we try to validate our own perspective while searching for similarities between the two. When the viewers’ ideology resonates with a filmmaker’s perspective, they readily accept it as the “only and absolute truth” and reject the mere possibility of someone else’s version. We can see the same affection for virality on YouTube as well. You can literally make a list of 10 hot topics if you want to go viral on YouTube, because the need for assertion is way higher than empathy towards a different perspective than yours.

This is how the formula of “successful” cinema originated in the time of Mr Bachchan. The fact that a majority of the audience of Hindi cinema at that time was still struggling for ‘Roti-Kapda-Makan’ helped to further establish this culture; because at a point when people didn’t have time to listen to their own voices (against the regime and otherwise too) at least someone was voicing the same concerns. The fact that this voice was of the legendary Amitabh Bachchan helped too.

However, we must keep in mind that this voice was never used for an outright denial of the regime – something that is center of story for Joker. The voice of Indian protest was always limited to outrage over a factory owner, an evil builder or a minister at max. Simply saying that filmmakers then were equally ignorant of the socio-economic situation of the country would be unfair and a bit too harsh, but a sense of fear can be read between the lines of their scripts. Not that Joker’s actions are praiseworthy, but it shows us to what extent insanity can go if not treated the right way when there’s still hope.

Nevertheless, our hero’s actions were always celebrated by the masses because their faith and expectations always rested in the character and not so much in the society. They cheered him for his vigilante justice and happily went home without even thinking about the bigger picture – the society as a whole. Sometimes I wonder which would be more detrimental – an unstable vigilante or a dispassionate society!

![M [1931] Is Still Terrifying After 90 Years](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/M_1931_thumbnail-768x477.jpg)

![Sorry We Missed You [2019] ‘MAMI’ Review – Repercussions of shifting Gig-economy](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Sorry-We-Missed-You-Review-768x432.jpg)

![Wushu Orphan [2019]: ‘NYAFF’ Review- An Emotionally Resonating Yet Under-cooked Tale](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Wushu-Orphan-highonfilms1-768x432.jpg)