If we are told to think about dacoits, the obvious image comes from celebrated western films in the 60s and 70s. When we picture them, we always focus on their fearlessness that comes from a lack of moral sense of what they are doing. We have only come to judge them from their appearance and fearsome demeanor. Rarely has a film tried to get to the bottom of this cliché. So, when a character in Abhishek Chaubey‘s Sonchiriya questions another dacoit about the nature of why he chose to become a baaghi [rebel], it pulls our heartstrings. Furthermore, the film sets out to achieve much more.

Lakhna Singh (Sushant Singh Rajput), who asks the question, wished to become a baaghi for the respect that they used to get. He really liked the control that a baaghi had over someone else’s fear. However, the merciless nature of their identity that attracted him earlier has now become a burden. He sees no point in it anymore. Even if a certain incident affected him deeply to think that way, it paints a broader stroke about a dacoit’s internal turmoil.

Similar to Sonchiriya: 2018: Revising The Revisionist Western – The Sister Brothers, The Ballad of Buster Scruggs and Damsel

As a result, we get an existential drama surrounding a bunch of outlaws who are on the edge as they are all trying to fight their way through life while trying to find a purpose for living. As they search for their own identity, the film stumbles upon death and religion – both of which, are crucial and relatable in the contemporary world we all inhabit.

Sonchiriya is set in the 1970s, when Indira Gandhi had declared an internal emergency. At a time when people started being more aware of their rights, being a dacoit become exceedingly difficult. As times changed, these outlaws who were living with the ideologies of the past started facing the heat up front. It seemed vile to let their masculinity earn them the respect that they once had. The times had brought them to a point where their terror was almost diminishing and there seemed no glory in being heroic anymore.

Also Read: Duck You Sucker (1971) – Leone’s Final Western

Rather than glory, being a dacoit was slowly turning into a matter of shame. Even if they escaped from a certain situation, they couldn’t escape from their own misery. The politics from the outer world didn’t matter at the time but it was evident that stronger forces were there to stop them. The film then sets forth a true struggle between life and death as the characters in the film start falling apart.

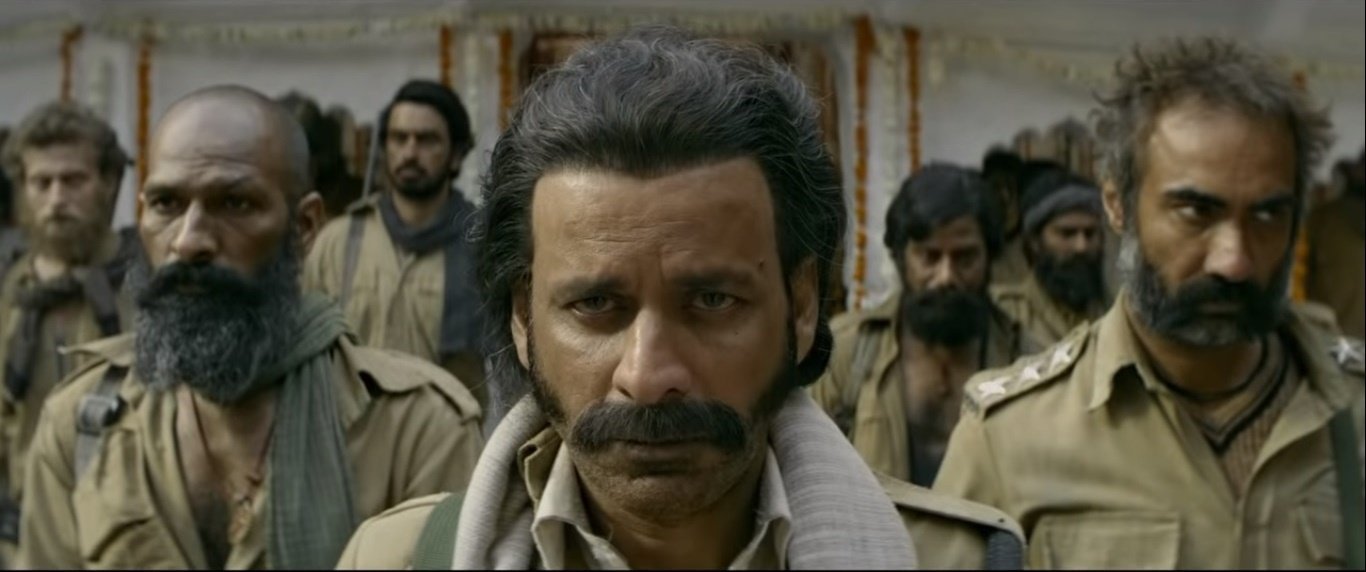

Lakhna Singh believes in the principles that the older dacoit Maan Singh pursued during most of his life. Manoj Bajpayee, who plays the character, was more of a messiah to him. So when he plans a robbery despite the police warrants against them, Lakhna’s resistance seems quite surprising. “Police unka dharam nibhayenge, Baghi baghi ka”, Maan Singh utters.

For a young dacoit who is engulfed in self-doubt and who is seeking a better reason to justify his living, this sounds quite amusing. The gang belonged to the Thakur caste, in a hierarchy not particularly kind to the ones that were lower in the ladder. So if the foundation itself is not just or fair in any way, do they really follow a certain faith? He asks Maan Singh, which in actuality is him questioning himself. The battle merely begins there.

Other than these two key characters, we get to see Vakil Singh (Ranvir Shorey) as Maan Singh’s loyal sergeant, Indumati Tomar (Bhumi Pendnekar) as a lady caught up in a similar turmoil and Inspector Virender Singh Gujjar (Ashutosh Rana) as a vengeful police officer. The drama seems little interested in the murder or bloodshed and more on the conscience behind any of their actions. Sonchiriya examines patriarchy and masculinity not just from the eyes of women, but also from the perspective of a man who is not considered masculine for choosing to be sensitive rather than violent.

Also Check Out: A Fistful of Dollars: The Arrival of Spaghetti Western

Pednekar plays a Thakur woman who is trying to save the life of a lower-caste girl. Even when the entire arc shouts of clichés, her character is essential to get to the title of the film – ‘a golden bird’. We meet the fictional form of the real-life dacoit Phoolon Devi, where we get to see another side of the spectrum. Patriarchy and caste deeply afflict the dog-eat-dog world that the film is set in – from the first frame that shows a dead snake crawling with flies to the very last shot, it solidifies this idea.

But not everyone wants to survive either. Everyone seems to have their own idea of redemption. If being alive means nothing but staying in the cages of anguish and despair, death is an inevitable option for them. With its harrowing reveals filled with enough tension to stick us to the screens, Sonchiriya conjures up the battle between life and death. While doing that, it also dwells on the perceived image of dacoits and the contradictions in reality.

The entire film never dwells on moments that paint a picture that would seem completely black-and-white. There is no clear protagonist or antagonist here. The cops are not completely sane and the dacoits are not entirely unsympathetic, cold-blooded murderers either. The character-arcs depend only on the preceding moment, which intensifies the fleeting nature of their existence and their ever-changing set of morals.

The performances are fitting, especially the ones by Shorey and Ashutosh Rana. Shorey is an underused gem and he shines just as he did in Titli or A Death in Gunj or any recent film he has been in. I wish that he gets more able directors who understand how to utilize his talent. Bajpayee does what he does the best and he’s reliable as ever. Sushant Singh’s performance stands out because of the role that suits his potential. Bhumi Pednekar is satisfying in the role, although not particularly striking.

Also Read: Disney+ Hotstar Multiplex To Release 2020 Bollywood Movies

What looks like a western at first, works more as a mood-piece. Sonchiriya is a mix of a thriller and black comedy, with the aesthetics of spaghetti western. The exquisite cinematography filled with the wide-angle shots, occasional bird-eye shots, and immaculate framing highlights the lives that are at stake, without ever submitting to grandeur.

The background score fits well with the overall pace and Choubey, just like his prior films, knows how to use silences to amplify the dramatic tension; instead of solely relying on music. He has surely come a long way in terms of aesthetics, with a film that will haunt you long after you have seen it.

![Amodini [1994] MUBI Review: Visual Elegance complimented by Scathing Social Commentary](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Amodini-highonfilms-768x413.png)