In my younger, and slightly less responsible days, I spent enough time in the back of cabs in Belfast, crawling the dark streets at 3 am trying to get home, to know that the guy behind the wheel was either the sanest person I’d met all day, or someone trying to hold it all together with a mix of delusion and duct tape. The crown prince of urban decay, Travis Bickle, in Martin Scorsese’s “Taxi Driver,” falls firmly in the latter category. But the thing is, he’s not just crazy. That would be too easy; you could dismiss that. Travis is a carefully painted portrait of what happens when social isolation, mental illness, and a broken society collide like three drunks in a revolving door.

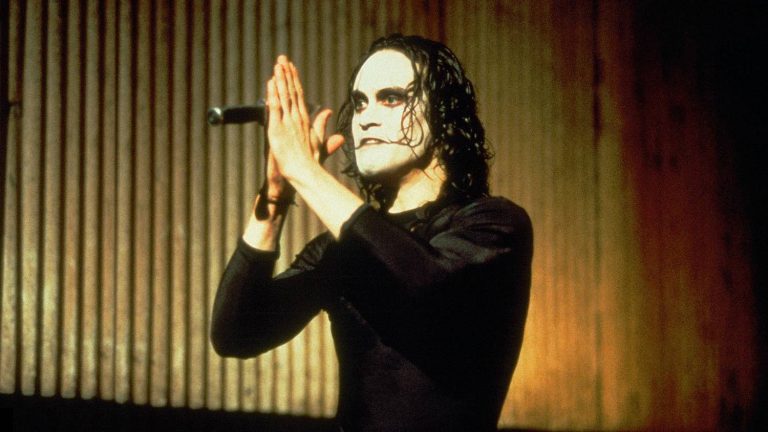

Paul Schrader wrote Travis. Martin Scorsese directed him. Robert DeNiro fully inhabited him. Together, they gave us one of the most uncomfortable dinner guests in cinema history. Someone you can’t quite look away from, even as he’s making a homemade gun rig and talking to himself in the mirror. He isn’t just sick, he’s a Rorschach test for everything wrong in post-Vietnam America. He’s a walking, talking symptom of a society that chews people up and spits them into the night shift.

Starting with the insomnia, as that’s where Travis starts. When asked by the cab company about his availability, he says, “Anytime, anywhere.” He can’t sleep anyway, so why not drive? And in that throwaway line, we get our first red flag. Chronic insomnia isn’t a mild inconvenience; psychologically, it’s a wrecking ball. Your perception is distorted; it feeds your paranoia and basically turns your brain into the funhouse mirror of its former self.

Travis cruises through the ventricles and arteries of New York like a corpuscle that’s lost its way. He sees the city’s nighttime detritus, the hustlers and sex workers, lost souls looking for something they’ll never find in the neon-soaked nowhere. He is disgusted by what he’s seeing but can’t look away.

Travis is the voyeur who hates the show but keeps buying tickets. The insomnia gives him an almost supernatural ability to witness. He sees everything, until seeing becomes a curse. Sleep would offer some respite, a break in consciousness, but for Travis, there is no intermission. His mind is grinding away, processing all the filth and degradation until he doesn’t know where the city’s sickness ends and his begins.

This point is important. Travis doesn’t just watch the corruption, he marinates himself in it, night after night, his taxi a confession booth with no absolution for anyone, least of all himself. The movie never goes into explicit detail about Travis’s war history, but it’s there in subtext, like blood under a fingernail. He was a Marine and received an honourable discharge. But also, he has that thousand-yard stare that says he has seen things he can’t unsee, and done things he can’t undo.

What we’re looking at, in our contemporary parlance, is most likely PTSD, though when this came out in 1976, it was still being called “shell shock” or “battle fatigue”. Or nothing at all, if we’re being honest. We were still pretending that young men could be sent to war, do unspeakable things, come home, and just…be fine. Get a job. Get a girl. Be normal.

Travis can’t be normal. For him, whatever normal was, it was lost in the jungle, or bombed city, or wherever the hell he was sent. He came home to a country that didn’t want to talk about its veterans, or look at them. It didn’t want to be reminded of what it had asked of them. So Travis ends up ferrying a cab around, alone with his thoughts, probably the worst thing for someone with his collection of symptoms: hypervigilance and emotional numbing, the intruding thoughts, the inability to connect with others, and the feeling that the world is fundamentally unsafe. Travis checks all these boxes. But he’s not getting help; he’s getting lonelier.

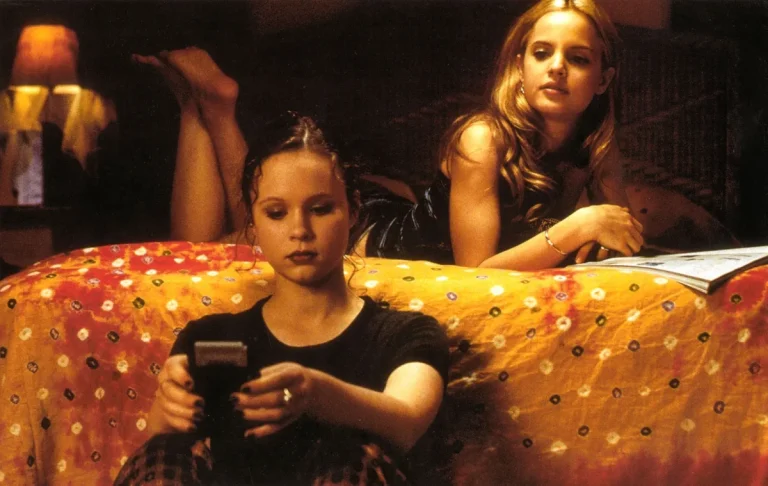

Insomnia and trauma may be the foundation, but loneliness is really the architect of Travis’s unravelling. He is a man who cannot connect. Not really, not in any meaningful way. He takes Betsy to a porn cinema on their first date because he really cannot see why this is inappropriate. He tries to become friends with a twelve-year-old sex worker not out of predation, but a misguided, paternalistic saviour complex.

That says more about his broken moral compass than any real desire to help. Watch him in the diner scene with the other cabbies. He’s physically there, but not mentally, really. He’s going through the motions of social niceness, but the wires that connect humans to each other have been cut. He’s like phantom limb syndrome, knowing something should be there but unable to use it or feel it.

And where it gets really uncomfortable is that Travis’s loneliness isn’t passive. It’s more than sad, it’s dangerous. Lonely people can become desperate. For meaning, a purpose, for something, anything to validate their existence. And if society offers nothing, you can’t connect with anyone, and the world looks like a degenerate cesspool, well…violence begins to look like clarity.

He begins to see himself as the solution to the problem. He will clean up the streets, wash the scum away, and be the rain that falls and washes the filth from the sidewalks. It’s messianic and grandiose thinking that emerges when a deeply isolated person decides their personal narrative is more real than reality itself.

We have to talk about the famous scene: “You talkin’ to me?” It’s Travis, alone in his run-down apartment, practising confrontations with pretend antagonists. Parodied to death at this point, but if we strip it all back, it’s genuinely frightening. We see a man rehearsing violence, creating scenarios where everyone else is a threat, and he’s the hero. This is disassociation. It’s someone who’s lost the ability to differentiate what’s going on in their head and what’s really happening in the world.

Travis is building an elaborate fantasy world, one in which he is significant and his actions matter, where he is not just some bland face in a crowd. The gun dealer scene earlier in the movie shows us everything we need to know about just how far Travis has drifted from reality. He is buying an arsenal as casually as we might buy groceries.

The guns become an extension of his body or his identity. They become the only things that make him feel powerful, to give him some sense of control in a world where he has none. And then we have the physical transformation. His mohawk, the military jacket, his newly imposed asceticism. He is shedding his old identity like a snake sheds its skin, but what he finds underneath isn’t healthier. It’s meaner, harder. He isn’t becoming himself; he’s becoming his symptoms.

Also Read: Is ‘Taxi Driver’ A Feminist Tale?

When Travis decides to assassinate Senator Palantine, we see somebody who is now detached from all moral reasoning. It isn’t politics or policy on his mind; it’s making a mark. He will force the world to see him. Even the fact that he pivots from trying to assassinate a presidential candidate to trying to “rescue” Iris when the plan fails shows us just how arbitrary his targets are.

This isn’t ideology. It’s not even about Iris, really. It’s Travis needing to do something to assert his existence through violence because every other avenue has been exhausted. He tried to connect with Betsy but failed. Travis tried to warn others about the filth he saw. They don’t care. He tried to fit into society. Impossible.

So violence becomes the only language he thinks people will understand. And the truly dark genius of Paul Schrader’s script? It works. He shoots up the brothel, killing the pimp and the mafia hood. He ends up a blood-soaked monster and becomes…a hero? The media call him a brave vigilante who saved a child. Iris’s parents write to thank him. The ending is ambiguous. Is it real, or a dying fantasy?

Either way, it suggests that we are so hungry for the simple narrative, for a clear hero and villain, that we will make a hero out of anyone whose violence we can rationalise. Travis’s obvious mental illness is reframed as heroism because he killed the “right” people. If he had assassinated Palantine, he would be remembered as a monster. Now, he’s a saviour.

That’s not just Travis’s tragedy. It’s ours, too.

What makes “Taxi Driver” more than just a character study of mental illness is that it indicts the society that produced Travis just as much as it examines Travis himself. We see 1970s New York as decaying, violent, and bankrupt. It’s filled with neon, trash, and broken promises. He’s a working man doing a shit job for shit pay with no healthcare or community, no support system. A lonely person in a city of 8 million people. Invisible, until he makes himself impossible to ignore.

Scorsese films New York as though it’s Hell, full of shadows and steam and sulphurous light. And through it rides Travis, Charon ferrying souls over the Styx, except he’s stuck there night after night, going in circles. The city is making him sick, but he can’t leave. Does he think he deserves the punishment? Or has he lost the ability to imagine anywhere else?

The movie never lets us off the hook by making Travis just crazy. He is crazy, and the world is nuts. He’s mentally ill and responding to real social decay. Both these things are true, and it makes him all the more unsettling. We can’t dismiss him as just some lone nut. We have to deal with the fact that if we take a broken person and marinate them in a fractured culture, violence isn’t just an aberration. It’s a predicted outcome.

One of the more sophisticated aspects of Travis’s unravelling is how the movie acknowledges its own unreliability. We are seeing it all through Travis’s eyes, and they are not to be trusted. Is the final scene real? Did he survive, and is that really Betsy smiling at him in the back of the cab? Does it even matter? We are forced to inhabit the view of someone whose grip on reality is tenuous at best.

We are complicit in his worldview, seduced by his narration, and follow his logic. But only in retrospect, when we step back, we realise just how unreliable our narrator is and how much we have been manipulated into sympathising with someone who is truly dangerous. From the inside, this is what mental illness can look like: justified, coherent, and logical. Travis doesn’t consider himself crazy. To him, he’s the only sane man in an insane world. That is the scariest part – the total certainty, along with the inability to question your own perceptions.

So, what are we really looking at when we strip away all the artistry, the Bernard Herrmann score, and neon-soaked cinematography? We have a clinical portrait of a man in extreme psychological distress. Travis is exhibiting symptoms of manic-depressive disorder, PTSD, social anxiety, insomnia, and what we now recognise as suicidal ideation, presenting as homicidal ideation. Travis self-medicates with pills and porn and empty calories, and engages in more risky behaviours. He can’t maintain appropriate social boundaries. He has built himself a delusional framework where violence is a redeeming act. Furthermore, he is affected by paranoia, isolated, and spiralling.

If it were a just world, someone would have noticed or intervened. He would have gotten help. But that world is not the one Travis lives in, and it’s not really the world we live in either. Maybe today we’re better at recognising the signs, but we still aren’t great at helping people before they actually break.

“Taxi Driver” endures exactly because Travis makes us uncomfortable in the right ways. He’s not a monster, as he’s too human for that. He isn’t a hero as he’s too broken for that. Most importantly, he is something in between, something we all recognise, even if we don’t want to. He is the result of mental illness, social neglect, and cultural sickness. Schrader and Scorsese weren’t trying to make us feel good. They held up a mirror and asked what we saw. Was it Travis, or was it us?

The movie doesn’t offer any answers or provide catharsis. It doesn’t offer a neat little resolution. It leaves us with Travis’s hollow eyes in the rearview mirror, still driving and circling. Still sick. Still out there in the dark, carrying passengers who have no concept of what is happening behind those eyes. And that, more than anything, is the real terror. Not that Travis exists, but that he’s still driving. Still alone with only his thoughts, and one bad night from breaking and doing it all again.

You talkin’ to me? Yeah. We’re all talkin’ to Travis now. Whether we know it or not.

![The Scoundrels [2019]: ‘NYAFF’ Review – A Standard Fare Which Could Have Stood Out with a Different Approach](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/The-Scoundrels-1-high-on-films-768x432.jpg)