Is Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver A Feminist Tale? Hollywood mass media makes vigilantism look cool: a man kicks down a door with blazing machine guns and indiscriminately kills everyone responsible for destroying his peace of mind. When the credits roll, he walks away the triumphant hero. Those Who Were Responsible have fallen in a bloody act of mass retribution. Justice is served! But is it not true that the philosophy that fueled the avenger’s conquest has only been reinforced as the way of the world that brought about the hero’s suffering? It is the same philosophy of domination that murdered his family and the same one that allowed him to justify vengeance.

There is something terribly wrong here.

Liberal feminist politics conveyed in Hollywood superhero films preach about the progressiveness inherent in cinematic representations of powerful women who don’t need men. While such representations can potentially be transformative, the issue is that, more often than not, these messages are less a celebration of female autonomy than a one-sided attack on the substantiality of maleness.

The current milieu among New Age Hollywood power feminists is the creation of the invincible paragon hero in comic book vigilante movies. Films like Birds of Prey and Captain Marvel relay the feminist message to audiences that the answer to empowerment is to combat the historical victimization of women by their tyrannical male oppressors. Hollywood feminist vehicles are now being used both as a medium for the declaration of political power and as a way to combat social abuse at the hands of the patriarchy. But the self-righteous cause of the Power-Feminist-Social-Justice-Warriors (P.F.S.J.Ws) turns out to be a fumbling of a basic understanding of human suffering.

Patriarchy, in the traditional feminist sense, is the deliberate historical exclusion of women from the acquisition of power-based status in American society. The general belief held by P.F.S.J.Ws is that patriarchy only psychologically damages women, affecting their self-esteem and relationships with others.

The assumption is that the system allows men unlimited privilege, making men the historical villains. New Age Hollywood feminism argues that women are goddesses transformed into harlots by patriarchy, and the answer to restoring their virtue is through the portrayal of the Paragon Super Heroine. The Paragon Super Heroine is the chosen one who finally arrives to upstage masculine authority.

But whether patriarchy is the source of universal suffering is not the issue. The surrender of our inner power (and the ability to remain objective) to the world outside our front doors is what ultimately is at stake. That surrender of inner strength always begins with the suffering of the individual.

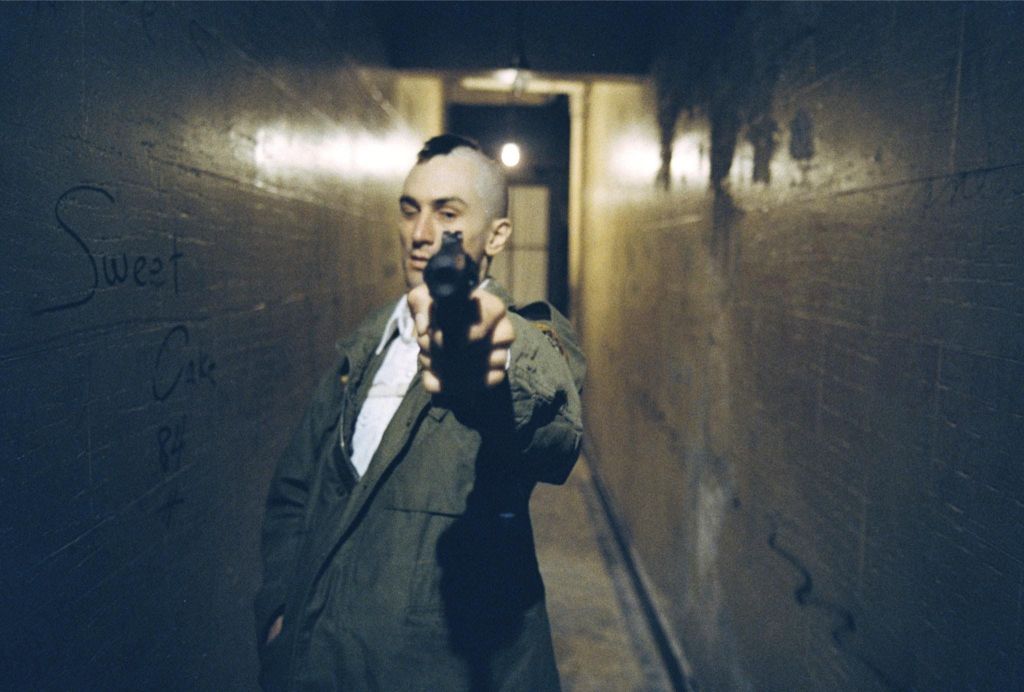

Travis Bickle, American cinema’s most beloved vigilante, commits the same error in Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver. When we look closely, we find a striking similarity between the faulty logic of the Power-Feminist-Social-Justice-Warriors and the acts of vigilante justice undertaken in the Scorsese film. The similarity is expressed in an interview Scorsese gave after the movie’s release.

In a conversation with Roger Ebert, the Irishman director summarized the thematic power of the film: it takes macho to its logical conclusion: the better man is the man who can kill you. This [film] shows that thinking. [It] shows the kind of problems some men have, bouncing back and forth between the goddess and the whores”(Ebert 46). Though graphic in its depiction of violence, Taxi Driver, Scorsese suggests, is deceptively macho. As a feminist story, Scorsese’s film represents two sides of the same coin: a denial by the feminists of how patriarchy is less a barrier to socioeconomic prosperity for women than an impediment to healthy psychological development in both genders and how such a lack of personal accountability specifically taints the worldview of men like Travis Bickle.

Related: 10 Films To Watch If You Love Taxi Driver (1976)

When analyzing the psyches of Travis Bickle and the P.F.S.J.Ws, one discovers that the pathology of victimhood underlies action and motivation. It leads one down a path of blame and irresponsibility.

Victimhood is the psychological basis for vigilantism.

It creates and perpetuates a way of thinking that misleads audiences into accepting a particular brand of justice as morally justified and emotionally liberating. It keeps people like the P.F.S.J.Ws from acknowledging how an institution like the patriarchy can be damaging to not only women but men as well.

Victimhood also prevents characters like Travis Bickle from recognizing how women themselves fundamentally have the power to make their own decisions about their allegiances to an institution. In other words, a pathology of victimhood renders us agents of our own individual suffering. Scorsesean feminism asserts that, left to its own devices, the patriarchy will eventually destroy itself. The Travis Bickle character and the P.F.S.J.Ws share a fundamental flaw that an increasing number of us within the current social climate possess: the externalization of accountability through the accusation of the practice of tyrannical power and the hypocrisy that results.

THE DRAMA TRIANGLE

Hollywood films like Taxi Driver and the politics of P.F.S.J.Ws demonstrate the paradox of vigilantism. But what does it mean to be a vigilante, and how is it an expression of a pathological cycling of victimhood?

Only one person seems to have stepped outside the bubble of cinematic grandeur long enough to pinpoint exactly how superficial Hollywood vigilantism operates. In 1968, psychologist Stephen Karpman aimed to understand the nature of interpersonal conflict. He devised a psychotherapeutic model to explain an individual’s process toward adopting an attitude of victimization. He called this process the Drama Triangle.

In a concise summation of how the Drama Triangle works, Vinita Bansal writes, “The flawed thinking that we adopt stems from an internal desire to be right…in how we feel, what we do, and how we expect others to behave.” (Bansal, “How To Opt Out Of The Drama Triangle and Take Responsibility”).

The flawed thinking inherent in the belief that patriarchy is an oppressive external reality (and how we actually create that reality by using the very weapons we feel keep us oppressed) is what defines the denial and assumptions of both Travis Bickle and the P.F.S.J.Ws.

Bansal continues: “The strong belief in the righteousness of our state leads to destructive interactions that drain our energy and devoids us from taking responsibility and creating the possibility of a better life for ourselves and others.” (Bansal). The internal desire to be right is the governing force of the Drama Triangle. It allows a person to shift responsibility away from herself, blaming others for her shortcomings regardless of the degree to which fault can be externalized. How Travis Bickle and the PFSJWs unwittingly collude with patriarchy and bring about their own suffering is the result of being trapped in the Drama Triangle.

The Triangle consists of three roles: the Victim, the Persecutor, and the Rescuer. Each role represents how we think, act, and react to external reality when others are the ones to blame. An individual can shift between these states of mind depending on whatever essential emotional need must presently be satisfied. This produces the psychological trap of victimhood and a distorted meaning of power and justice, creating a cycle of denial. In essence, this is what both creates and perpetuates the Drama Triangle since it “provides an escape path to hide our underlying feelings and prevents us from addressing our real problems.” (Bansal).

Also Read: 10 Best Films of Martin Scorsese

Hollywood vigilantism, depicted in Taxi Driver and the politics of girl-power superhero movies, is an illusion of heroism perpetuated by misguided souls arrested by the Drama Triangle.

Vigilantism takes on a different meaning when viewed through this lens. It becomes the manifestation of the denial of resentment from perceived ostracization from regular society and the subsequent expression of that resentment with swift, finger-pointing, angry justice. In Aeon J. Skoble’s essay God’s Lonely Man: Taxi Driver and the Ethics of Vigilantism, he explores whether vigilantism is justified as an ethical practice.

Is vigilantism based on a substantive belief, or is it only a matter of individual opinion? This question, for Skoble, would guide the answer of “how we are to differentiate justice from revenge and madness” (Skoble 24). He believes that vigilantism takes on two forms: self-defensive and adventuresome. The former is far less problematic than the latter since its very definition is the justification of violence when an imminent threat is posed to one’s person. When trouble approaches you, it’s your right to engage and thwart it. Therefore, not much analysis is needed for self-defensive vigilantism. But as a concept, self-defensive vigilantism, when viewed within the context of the Drama Triangle, can provide the basis for a much deeper psychological issue.

The Victim

Of the three roles, the Victim provides the foundation for the pattern of cycling through the Drama Triangle. The Victim believes:

…someone or something else beyond their control is responsible for their situation [and] prevents them from taking responsibility for their own condition and denying the power to change their circumstances…The feeling of being victimized by a person or a situation builds an external dependency beyond their reach. Lack of authority and willingness to take charge of their own life and its circumstances makes them rely on others to solve their problems (Bansal).

For someone to become a vigilante, there must first be a feeling of being victimized. Self-defensive vigilantism is a response to a denial of rejection and identification with victimization when a person feels at the complete mercy of external reality. Since the victim role is the foundation of the Triangle, self-defensive vigilantism is the parent source of the suffering. It is the base justification for the eventual vigilante crusades of Travis Bickle and P.F.S.J.Ws.

The need to become empowered for Travis and P.F.S.J.Ws lies lateral with a sense of victimhood. Finding some facet of external reality will validate that sense of disenfranchisement is necessary.

Travis’s need to play the victim is what drives him to ask the beautiful campaign worker, Betsy (Cybil Shepherd), out on a date. He turns Betsy into the Paragon Queen through his admiration of her from afar. Doing so holds the promise of transcendency above anything in his life that came before: the loneliness, the frustration, the aimlessness, the powerlessness a once-proud soldier may experience.

Betsy becomes the solution to a suffering pariah like himself. She’s the personification of the goddess beheld by the victims of patriarchy. This sort of worship at least places the victim on the right track because the act of showing vulnerability may lead the victim to adopt some semblance of a sense of responsibility for oneself: Being a victim is different from being vulnerable. A vulnerable person does not lose control of their condition. They recognize it and fight back to get out of that state. A victim, on the other hand, thinks they cannot do anything to influence or change their state” (Bansal).

Awareness of our vulnerability can be an act that leads to taking responsibility and moving toward real empowerment. Unfortunately, instead of undergoing self-reflection through feeling accountable as part of the process of “getting one’s act together,” the vigilante, out of self-defense, directs his sense of worthlessness out onto the world.

When Betsy rejects Travis after their second date, Travis plunges even deeper into isolation. He ultimately turns Betsy into a symptom of the larger systemic problem that causes him pain. But he’s unaware of his error: of all places, he takes his date to a porn theater. Instead of connecting through vulnerability by discovering what they truly have in common, Travis is so eager to win at dating, to do what dominator culture has taught him, that he fails to humanize Betsy. Being trapped in the Drama Triangle makes it difficult for us to find humanity and complexity in others.

The Persecutor and The First Stage of the Adventuresome Vigilantism

Vigilantism is an act of self-defense in response to salvaging our psychological and emotional well-being. The manifestation of this self-defense is in pointing fingers. Once the pathology of victimhood has taken full root in a person’s life, focusing blame outward is the natural response in tracking down the source of the pain. It is the next step in the transformation of the vigilante. But to place blame on others is to deny responsibility.

Ironically, the denial of accountability is the act of surrendering power.

It is the act of allowing our external world to impact our inner strength negatively. True empowerment is the inverse: understanding your inner power, its potential effects on the external world, and using our inner reality to affect positive change upon it. It also consists of the negotiation of the relationship between our actions and the consequences of those actions.

One does not cultivate a sense of responsibility through the arbitrary formation of enemy-spotting and the subsequent eradication of that enemy. Yet this is the role of the Persecutor in Karpman’s Drama Triangle. It is also the character and nature of adventuresome vigilantism defined by Skoble.

Superheroes, if rarely, are ever portrayed as acting out of self-defense but in defense of others. In other words, they must go looking for trouble to be superheroes. In rendering the service of a greater good, the hero must face the potential transmogrification into a person she may not be interested in becoming. This is usually a prominent theme for the hero’s transformation: resisting the instinct for self-preservation. Because of self-preservation, Peter Parker’s uncle was murdered. His lesson was that he needed to use his powers to protect the people he loved. If Bruce Wayne chose self-preservation over duty, the Bat Signal would keep everyone awake and too tired for work in the morning. Vigilantes are not forced to move beyond self-preservation to answer a higher calling. In a sense, vigilantism is self-preservation because self-preservation is the protection of the ego.

Superheroes use their internal world to make sense of external reality. They do not process from the outside in but from the inside out. Vigilantes process the world by way of the former. They use external reality to justify what is happening to them internally.

Self-preservation, then, represents the dark side of self-defensive vigilantism in that it is not only literally the act of defending against physical harm but also a defense against psychological and emotional terrorism.

The vigilante points to the external world as the culprit, and this is the infrastructure of adventuresome vigilantism. For Skoble, vigilantism of the adventuresome kind is the major point of contention since it is the style of vigilantism that seems to “characterize Travis’s later actions and most of what comic book superheroes spend their time doing” (Skoble 24).

The tumor of doom that sprouts when self-defensive vigilantism is carried out without assuming responsibility, are the self-righteous path of adventuresome vigilantism.

This particular form of vigilantism defines the difference between justice and madness. Skoble points out rightfully that human beings, left to their own devices, cannot be relied upon to carry out justice. We depend on the law to enact justice on our behalf. Acting independently of the law is only done out of primal instinct, bitterness, frustration, anger, and passion.

The process of transitioning from Victim to Persecutor is the first stage of adventuresome vigilantism:

“A persecutor or villain has a tendency to control, blame and threaten others [while] living with a false sense of superiority. They put on a grandiose act in an attempt to hide their fear or failure and get defensive when things do not work out the way they anticipated…pinpointing problems and directing others as the primary cause of those problems. The validation of their beliefs comes from seeking a situation or a person to hold accountable for their problems and trying to manipulate them in working their way.” (Bansal).

The patriarchy becomes the target of persecution for the PFSJWs and Travis Bickle.

For the PFSJWs, it allows for the direct blaming of the outside world for one’s shortcomings. Such reasoning does not demand the pain of achieving insight through painstaking mental, emotional, and psychological effort. The constant battle against the antagonism of external reality offers an oversimplified, singular solution to a person’s suffering: patriarchy is wholly responsible for one’s unfavorable lot in life, and its annihilation means the improvement of one’s circumstances and the betterment of society at large.

But the denial of accountability by the Persecutor can only mean that one is doomed to ironically express their own brand of domination to rival the oppressive force in question. It can only be this way since the answer to victimhood is always swift-and-hard justice in the form of self-righteous power. After getting rejected, Travis is left in a state of confusion. The awareness of vulnerability that helped him engage the world to find meaning in social acceptance has led him to hit a brick wall. Though Betsy is a mature, capable adult and responsible for her decisions about her dating life, Travis is not. The only way he can make sense of the rejection is to switch from feeling powerless to finding someone to blame. He externalizes the rejection, confronting her at her job for answers in a hostile fashion.

Instead of taking responsibility for his emotions, he decides to pursue Senator Palpatine, the man he believes is holding her freedom captive. As a symbolic patriarchal figure, Palpatine represents a systemic, dominating force that needs to come undone. It is a huge irrational leap that not even Skoble can rationalize in any profound way: “The problem is that Travis is not entirely sure what it is he needs to stand up against. There’s a critical distinction between fighting evil and fighting perceived evil. [p. 26]

As a feminist tale, the senator is the first straw man encountered in Taxi Driver. Travis assumes that Betsy has chosen Senator Palpatine over him. But wait…Palpatine is what’s wrong with the men in this world! For Betsy to recognize her folly, the senator must die!

Travis thinks Palpatine should be destroyed, but his encounter with the security guard during a failed assassination attempt demonstrates that the senator’s villainy is not transparent to anyone but Travis. The vigilante in Travis interprets this as a superhero’s keen instinct while being blind to what this really is: an illusion of heroism. He cannot validate his victimhood and the necessity for killing Palpatine.

“Other than as an unwarranted influence from Betsy’s rejection,” Skoble observes, “there’s no evidence in the film whatsoever to suggest that Palpatine is an evildoer.” (Skoble 26).

The PFSJWs have the same issue.

They cannot demonstrate the need to dismantle patriarchy as long as the source of the suffering entails the complicated analysis of the existence of an oppressive system. One must point to more concrete practices to show that such a tyrannical structure permeates everything.

In Birds of Prey, the heartbroken Harley Quinn roams Gotham’s streets after being dumped by The Joker. Everyone is in the know. They see the pain, her hopelessness, and her consternation over her rejection. It is an acknowledgment of her victimhood, having been betrayed by her patriarchal daddy/lover/role model/mentor. Harley is no longer integrated into the hierarchy of patriarchal privilege. Disenfranchised, she becomes the target of bitter thugs who owe her one, particularly Black Mask (Ewan McGregor).

In true power-feminist-comic-book-vigilante philosophy, the plot is symbolic of Harley’s realization that she is strong and independent without The Joker, but not before the story represents, as a meta-narrative, the Karpman Triangle.

As a victim, Harley gets rejected and humiliated by The Joker. She is soon raiding a police station taking (symbolically) her frustration with men out on the officers in a scene designed to show the audience how tough she is, patriarchal daddy or not. A petite vixen mows down armed men with a baseball bat.

The subtext of this scene is a message brought to us by way of the girl-power-feminist-Hollywood-meta-narrative that even males in authority are no match for the concentrated efforts of determined white female superhero warriors. It is a scene that serves to reinforce the message that men are the objects of blame and, thus, become the supervillains of the meta-narrative. Being booted off the top of the hierarchy has caused Harley to become the Persecutor, assaulting the men in the station because she needs someone to blame.

It is a politically symbolic attack.

The perception of reality is the difference between self-defensive and adventuresome vigilantism. It is also the difference between victimhood and vulnerability. When the vulnerable person experiences the intrusion of pain and suffering from the world outside of her, she uses her inner strength to mitigate the situation. It can lead to the creation of positive change. When the victim has the same experience, she uses her feeling of discomfort to sow greater agony and destruction.

When The Joker dumps Harley Quinn, her broken heart is an opportunity to make the world feel her pain. As the Persecutor, she destroys the power plant as a message to Gotham that she is no longer integrated into a patriarchal-dominator society. She is now a free agent. The destruction of the power plant is the call to place blame somewhere in a world where a man has decided that she be rendered powerless and alone.

Integration is a means of making a compromise with the world. It creates a pathway to finding fulfillment and happiness on our own terms through cultivating value in our lives and then using that to leave our mark on the world in a healthy manner. This is what ultimately sets us apart from the system. To engage with the external reality violently and in an accusatory manner is a surrender of that power. And now we are stuck perpetually cycling through the Drama Triangle.

The Rescuer

When the vigilante surrenders accountability over his actions and feelings through playing the blame game, his assertion of power ironically colludes with the disempowerment of those he swears to protect. The opacity of an oppressive enemy we are all struggling to resist, which must be dismantled, makes it difficult to justify our cause.

So something else must be done.

In order to persuade people of a cause, there must be someone to rescue; and it has to be someone who visibly appears to need rescuing. The final stage in the Drama Triangle is the role of the savior:

The hero or rescuer establishes their own sense of well-being through others. They feel good and worthwhile about themselves by being in the act. This mindset that drives their actions is not one of genuine care for others but rather a desire to feel good about themselves by being in the act. As a result, they promote dependence instead of empowering the victim and helping them to take responsibility for themselves…the rescuer will get [the victim] out of this state [of helplessness], [but] they actually derail them from improving by constantly providing help. Since the rescuer does not address the underlying root cause of the problem and only solves it superficially, they wait for the issue to occur again to uplift their feel-good factor by getting a chance to rescue again (Bansal).

This is the essence of the Hollywood superhero vigilante! There is nothing sexy about teaching others how to become their own saviors when you can be their savior. You can appear and reappear to save the day to feel valued, validated, and needed. With a designated victim to save, the Persecutor transforms into the Rescuer. The Rescuer requires a) someone to rescue, i.e., a victim, and b) someone to rescue the victim from.

Tangibility is key to being the Rescuer. As Persecutors, vigilantes need someone to destroy; someone in front of her or him to place blame so they can superficially move beyond victimhood and give substance to the justification of the externality of fault. When the nature of the individual victimization grows into a uniform experience for a group as a consequence of externalizing one’s suffering, perceived social failures can justify any behavior on the part of the Rescuer in the name of serving a greater good. The hero must prevail, or else the world (her world) is doomed.

The narrative of Birds of Prey ultimately adopts the stance of The Rescuer through adventuresome vigilantism with its portrayal of Black Mask as a sadistic hunter. Relentless in his pursuit of Harley and the other girls, he is the tyrannical male personified. It becomes the justification for his destruction. Adventuresome vigilantism is disguised as self-defense by the meta-narrative with the arising need to defeat Black Mask and his men when the girls are backed into a corner. Even though they are technically criminals themselves, the lead females are made into sympathetic characters because they are either being pursued, rejected, degraded, or accosted by the oppressive agents of patriarchy (who are always male). Acting in accordance with the Drama Triangle, the meta-narrative must turn these rebel women into Rescuers to properly showcase their female empowerment and true independence.

However, unlike Scorsese’s film, the movie is not a critique of vigilantism and patriarchal macho heroism but rather a celebration of its use. Like Captain Marvel, the girl-power-feminist-Hollywood-meta-narrative uses female bodies, particularly white female bodies, as a vessel for its justification of patriarchal power switching hands between genders and the assumption that doing so would be an act of unadulterated justice and benevolence.

Through this process, the meta-narrative constructs The Rescuer as the feminist paragon hero. These women become glamorized examples of role models for young girls who witness such characters come to power at the expense of dispossessing men.

One convinced of patriarchy as the eternal source of blame believes in the goddess before patriarchal contamination. This philosophy is the calling card of the PFSJWs that patriarchy is a historical and infinite social epidemic poisoning everything it touches. If women are unlucky and downtrodden, it is because patriarchy controls them all, keeping them locked in a pattern of suffering that comes with living in a man’s world. As victims, the power feminists can blame the collective pain on external reality and, therefore, detach from accountability.

In Taxi Driver, Skoble unconsciously draws attention to the transition from Persecutor to Rescuer that takes place in Travis’ mind. “It’s relatively uncontroversial that Iris needs to be rescued from the Mafia, but it is far from obvious that Senator Palpatine should be killed.” He then proceeds, “Regardless of what he thought he might accomplish by assassinating Palpatine when he realizes that that won’t work, he sets his sights more microcosmically: rescuing Iris.” [p. 26]

After the hand of an oppressive male pulls the teenage prostitute, Iris (Jodie Foster), out of his taxi, a strong epiphany dawns on Travis: the deprogramming of the goddess begins in girlhood! Though quite literally a harlot, Travis concludes that the poison of patriarchy has contaminated Iris’ innocence. Since the domination of Iris can be more readily identified (unlike Betsy, this teenage girl is being controlled by a more tangible force), Travis can assume the role of a superhero.

The new straw man is a pimp named Sport (Harvey Keitel), and Iris is the perfect victim. Unlike Betsy, Iris can be convinced that she is being taken advantage of. In Travis’s mind, Iris has been made into a whore against her free will. As a Rescuer, he tries to convince Iris of her situation: Sport has manipulated her into thinking he has her best interests at heart. While there is a scene in the film that clearly shows this to be the case, Travis ultimately is no different from Sport in the end. He is operating out of necessity to feel like a hero by persuading Iris of her victimhood.

As a Rescuer, Travis can save Iris because she has been disempowered by the same society that has done an equal injustice to him, both through rejection in his romantic life and disownment by the civilized world of his warrior-animal instincts. But like the PFSJWs, Travis is blind to his own collusion with patriarchy and is only opting to adopt a stance of righteous power to serve his own self-fulfilling agenda.

Playing The Rescuer is only a false show of responsibility, for it allows a destructive co-dependency to manifest where the fabric of morality can be twisted to allow the hero to claim ownership over the victim’s destiny. The hero can continue to deny accountability for his actions and feelings as a consequence of this justification.

Resentment is played out in the glorification of violence, fulfilling a misguided feeling of worthiness. This ironic message is a theme in Taxi Driver.

Seeking validation through being the one to bring order to the streets ironically alienates oneself from society, becoming just another patriarchal king (or queen) above it all.

Sometimes the most dangerous hero is one who is not summoned. Vigilantes cannot see the gray matter. They cannot view the world as complex and three-dimensional. They only act in extremes because they can only see the world through black and white. Provocateurs like the PFSJWs and Travis Bickle are both guilty of seeing women only as victims. (In Scorsese’s words, as either “goddesses” or “whores” in desperate need of rescuing). But as we’ve seen, such thinking only seals a fate of self-destruction.

The difference between self-defensive vigilantism and adventuresome vigilantism is the difference between courage and stupidity, awareness and naivete, and responsibility and immaturity. The empowerment process for Travis Bickle and PFSJWs is the doomed transition through the roles of the Drama Triangle.

Solutions

The Drama Triangle ultimately shows that people like Travis and the PFSJWs become unwitting agents of their own oppression. What needs to be understood is that there is no oppressive system that manifests a specific embodiment agent that does the terrorizing. Everyone is responsible for how the system functions and perpetuates itself!

Such a concept is explored in profound depth by journalist Isabel Wilkerson, who ingeniously applies the social logic of the Indian caste system to the plight of African-Americans in her work Caste: The Origins of Our Discontent. Where we are born in the caste system, she argues, determines identity, association, and privilege based on arbitrary innate traits like race and gender:

The enforcers of caste come in every color, creed, and gender. One does not have to be in the dominant caste to do its bidding. In fact, the most potent instrument of the caste system is a sentinel at every rung, which forswears any accusation of discrimination and helps keep the caste system humming (Wilkerson 244).

When an individual is made aware of his vulnerability to the external world, self-defensive vigilantism comes to represent a shift from imprisonment inside the Drama Triangle to liberation from the cycle through embracing accountability. The self-defensive vigilante sees opportunities for social rehabilitation through internal reconstruction. Acceptance and willingness to understand our complicity in keeping the Triangle alive make the terms self-defense and accountability synonymous with the truest meaning of empowerment.

Bansal writes, “Willingness to accept the contribution of your own actions can shift the mindset to see a different reality–what you see, how you perceive others, how you think and why you choose to react…Just by choosing the barrier to be more open, we can give permission to our mind to form new connections and discover new realities…” (Bansal).

Isabel Wilkerson’s theory of an American social caste hierarchy highlights the dangers of adventuresome vigilantism (as a product of being emotionally trapped in the Drama Triangle) in a story she shares of an experience dining with a friend.

The friend became offended and outraged by the negligence of the waiter. Customers who were seated long after them receive more prompt attention and are even served their food before the two ladies barely get appetizers. Growing impatient and hostile after numerous tries to get the waiter to pay them the same courtesy, the friend has had enough. She finally chooses to accost the man and virulently accuses him of racism:

With all the ruckus, the manager came out to see what was going on. As it happened, the manager was a petite African American woman who seemed cowed by the ferocity of this newly minted anti-racist, anti-casteist, upper-caste woman standing before her, enraged at the unaccustomed humiliation. The manager apologized profusely, but my friend was having none of it. (Wilkerson 368).

Isabel’s upper-class white friend felt victimized by the waiter’s apparent indifference and, at once, made him and the entire restaurant the target of persecution. Being denied prompt service and attentiveness caused resentment in Isabel’s friend. Vulnerability to the waiter’s negligence created a sensitivity to the injustice of the external world on her friend’s individual being. She could only look at Isabel and share disbelief and discomfort. This eventually caused the friend to commit to self-defensive vigilantism–the need to defend one’s emotional and psychological pain.

While adventuresome vigilantism creates destruction in one’s wake, self-defensive vigilantism, when guided properly, can forge an opportunity for finding accountability for our pain and suffering. Doing so allows us to find enlightenment from the reasons for our anguish and lead to the cultivation of happiness. This is the consequence of healthy integration into a seemingly incompatible world. But the first step is always assuming accountability and surrendering the feeling of superiority.

Because the friend is oblivious to Isabel’s feelings about the situation in the restaurant, she can only recognize her own pain and assume Isabel’s. Choosing to confront the restaurant staff over the negligence was the white female friend’s adoption of The Rescuer role. But as we learned, the presumption and projection of one’s personal emotional anguish onto other people lead The Rescuer down a potential path of alienation and self-destruction. Wilkerson shares, “People at other tables were now looking over at me when I had not wanted the attention. I had no interest in making a federal case out of this. If I responded like that every time I was slighted, I’d be telling someone off almost every day.” (Wilkerson 367).

The friend has now run the risk of alienating Isabel through her act of playing hero. If she had considered her friend’s feelings and experiences with such encounters at the moment, she might have broken the Karpman cycle. Instead, she allowed her outrage to spur her into adventuresome vigilantism, which occurs when one adopts The Rescuer’s stance. It is the act of arming The Victim with a sword that she blindly wields to swing at any obstacle on the path to finding justice.

Adventuresome vigilantism is the most perverse form of justice. It is also the form most glamorized in Hollywood vigilante movies.

Travis preaches to Iris about her sin (The Persecutor blaming the victim) but swears to rescue her from the pimps (The Rescuer saving the victim) while all the while getting to feel celebrated and worthwhile (the Victim needing something external with which to attack to have his feelings validated). Patriarchally programmed, Travis, is more interested in destroying his enemies than saving Iris. As he did with Betsy, he denies the girl a complex humanity in order to salvage his own. He is not interested in understanding Iris’ thoughts, feelings, and motivations behind her lifestyle choice. He only wants to justify his own to fulfill his sense of agency.

What he does next is the pathology of the Drama Triangle and adventuresome vigilantism reaching a crescendo. A building full of men meets their bloody demise as a frightened Iris begs Travis to stop. Is she not an agent of the patriarchy herself for begging for the lives of these men to be spared? If Travis had put more thought into who the lowlives of New York really were, wouldn’t he have eventually counted Iris as one? She is a prostitute, after all. She should die too!

But the Adventuresome Vigilante/Rescuer needs someone to protect. Modern-day feminists might not view a female pimp as an agent in the oppression of women, colluding with a patriarchal system of domination. Instead, it is more likely she will be perceived as an empowered woman tricking out girls just as good as, if not better, than the male pimps. But what makes her behavior any less pathological?

Isabel’s reaction to the scene at dinner brought discomfort and humiliation. This is the consequence of Hollywood’s adventuresome vigilantism manifested in real-life situations. The frustration and resentment that caused her friend to switch on Rescuer mode inadvertently caused Isabel to grow resentful of her aggression. It is the sort of personal backlash that results from The Rescuer’s designated victim. As an observer from the outside, Isabel possessed clarity about her friend’s state of mind. She is not trapped in the Drama Triangle. She clearly witnessed the clash of worlds between her friend’s consistent, privileged life, the sudden disdain she experienced at the restaurant, and how it bred a certain pathology of social outrage that made the friend’s suffering define the ambiance of the place.

At that moment, the upper-class friend unwittingly becomes an agent of the Drama Triangle and takes poor Isabel along for the ride: “She stormed out of the restaurant, and I walked out with her. It took a while for her to calm down.” She continues, “Part of me resented that she could go ballistic and get away with it when I might not even be believed. It was caste privilege to go off in the restaurant the way she did…it was so alien to her, it so jangled her, that she blew up over it” (Wilkerson 368).

The vigilante turns from an outraged victim to an angry, self-righteous hero in the blink of an eye. Giving our power away causes us to feel that we need to take it back forcefully. It is always better to maintain control and a sense of self-reflection and objectivity to both emotionally and intellectually interrogate the way we feel and why we feel the way we do. The dark side of self-defensive vigilantism always inevitably leads to adventuresome vigilantism, which may bring indirect harm and embarrassment to the ones we swear to protect. Becoming a hero on impulse is not always as glamorous as Hollywood movies make them out to be.

As Isabel was urged to teach her friend that day, redemption from the Drama Triangle can be found in embracing the light side of self-defensive vigilantism. Expressing the light side of self-defensive vigilantism is the antithesis to the pathology of self-righteous, violent social justice glorified on the Hollywood screen. It entails recognizing the vulnerability to the susceptibility of unfair treatment in the first place. Consequently, it allows us to maintain power over our faculties and, ultimately, our reactions to an unjust situation. It necessarily curtails victimhood (the total relinquishment of power to the external world). Adopting a victim mindset makes one a very dangerous force of nature. It lays the foundation for reckless adventuresome vigilantism and blind heroics.

Isabel’s friend could not see that she comes from the very world that perpetuates the very indignities people like Isabel suffer on a regular basis. Those who either enter or are trapped in the Drama Triangle may be oblivious to how comfortable and privileged their external world is. This is also another source of resentment for those closest to them. Bansal writes, “Willingness to accept the contribution of your own actions can shift the mindset to see a different reality–what you see, how you perceive others, how you think and why you choose to react…Just by choosing the barrier to be more open, we can give permission to our mind to form new connections and discover new realities” (Bansal).

While the uncomfortable experiences in the restaurant allowed her friend to see how Isabel, an African-American, is often treated in everyday social situations, her outrage prevented her from seeing how the upper-class paradise she’s occupied her whole life informs both the privilege of her reaction and the treatment of Isabel. The experience in the restaurant was an opportunity for two women from different cultural backgrounds to share vulnerability through communication and mutual understanding of these differences and how it shapes their respective realities and interactions with one another.

Travis has an opportunity for accountable self-defensive vigilantism when Iris enters his taxi for the first time. Instead of driving away as she orders, he opts to meet her later on his own terms to convince her of her victimhood. He does not allow Iris to feel empowered by simply obeying her command to drive. Travis allows the insistent patriarchal presence to grab her out of the car (even though he’s figured out with Betsy that “patriarchy” is the problem) and then later plays the hero, robbing himself of a critical moment that could have created a real friendship with Iris. Travis could have become a mentor, helping Iris find her own sense of agency and self-worth by showing her how she could come into her own power:

The first step to shift from a rescuer role is to accept that your work is not selfless, it does more harm than good to others, and it’s damaging to your own self…believe that people can take care of their own. Shift from creating dependency to enabling self-responsibility, from providing solutions to letting them find their own solutions, from supporting the victim mindset to encouraging a creator. Act as a coach–listen actively, empower others, encourage them not to give up, and help them learn from mistakes (Bansal).

The first step to achieving such a connection is the assumption of responsibility. This in and of itself is a liberating act that frees the person from the perpetual loop of the Drama Triangle. Bansal recognizes the substantial role our environment plays in the construction of an individual’s ability to resolve a problem. Not being aware of how we come to reason through our suffering is a losing game that keeps us susceptible to the pathology of the personalities of The Victim, The Persecutor, and The Rescuer.

Self-awareness is key to taking responsibility for our emotions, acknowledging how we engage the world, and monitoring how we govern our relationships. “It requires questioning our very thoughts and beliefs that have gotten us so far in life. But what if the same opinions and beliefs are now holding us back,” Bansal recognizes (Bansal).

The environment Isabel’s friend grew up in allowed her to perceive an injustice when a certain expectation she took for granted was not met. Her outrage ignited a sense of self-defensive vigilantism over being ignored and her expression of this to the waiter. But as the Victim, she could only consider her own discomfort and the assumption that the entire staff had it out for the two of them based on race (even though the manager was African-American). The Persecutor attacked the integrity of the establishment and threatened to damage its reputation. This marked her transition into adventuresome vigilantism, where the friend becomes the hero by believing that she is defending the honor of her black friend.

Travis can only see Iris as a corrupted harlot who desires to escape her situation but lacks the resources to save herself. This convinces him that Iris has not come across her plight as a consequence of her own sense of agency. That fleeting moment in the taxi could have been a window for Travis to feel responsible for his vulnerability and to share that vulnerability with Iris to discover the kind of people they really are. They would come to understand that, even though they are both products of the system, they do not have to be slaves to it!

Understanding this frees us from the Drama Triangle. Bansal recognizes that this is a more intricate and challenging process than, say, annihilating a room full of thugs with machine gun blasts: “It requires questioning our very thoughts and beliefs that have gotten us far in life. But what if the same beliefs and opinions are now holding us back? When dealing with a conflict, our natural tendency is to act on the first thought that comes to our mind (Bansal).

Moving from persecutor to hero, the office workers similarly sacrifice a potentially liberating self-defensive vigilante mindset based on discovering internal fault to adopt an accusatory externalizing adventuresome stance. Leftists have made attempts to label certain behaviors as being indicative of the existence of oppressive institutions.

A woman who observes her male coworkers roll their eyes or giggle while she’s speaking up during a meeting is taught by social-justice-feminism to perceive such expressions as chauvinistic or even passively dominating. She learns to be a victim. But she decides to do something about it: Being a victim is different from being vulnerable. A vulnerable person does not lose control of their condition. They recognize it and fight back to get out of that state. A victim, on the other hand, thinks that they cannot do anything to influence or change their state (Bansal).

There is no acceptance of personal responsibility in the office that would allow both genders to see their contributions to workplace harassment in order to work toward compromise, generating favorable conditions for both women and men. Instead, men are cast as villains out to oppress and harass women. Therefore, the smallest move can be interpreted as a microaggression.

This simply breeds paranoia and distrust. The more we give power to the external world’s influences, the more we identify with victimhood. An eye roll or a chuckle is interpreted as a “microaggression” to keep someone in line. Though there may be validity in the arguments condemning such trivial acts, the difference between victim-led adventuresome vigilantism (or #metoo witch hunting) and community-inspired, life-affirming self-defensive vigilantism (or empowered negotiation) is what ultimately informs how effectively and responsibly we respond to such offenses and who we are as individuals.

Remember that the difference between self-defensive and adventuresome vigilantism is essentially the difference between a victim and a vulnerable person. That difference is the perception of reality. And also, remember that we only uphold a caste system, or a hierarchy of power, by playing the victim. In other words, our perception of reality is the extent to which we feel the external world affects what we see, how we perceive others, how we think, and why we choose to react.

Suppose the same female employee caught sight of fellow female co-workers rolling their eyes at her attempts to express her opinion during the conference. Is it patriarchy? Is it a microaggression? Can the oppressive structure be blamed when a woman is an agent? Is one a victim of the system or of the individual? Adventuresome vigilantism necessitates the hunting and killing of the latter to dismantle the former. But what is to be done when the latter does not resemble the former? We come to realize that there are no victims, only players, with everyone doing their own version of the domination dance. This is what Hollywood vigilantism argues: why power is always justified on the other side. Otherwise, how do we know who is truly right and who is absolutely wrong?

Also, Read:

Anatomy of: Taxi Driver Scene – “Late for the Sky”

Masculinity and Ignorance as themes in neo-noirs: Taxi Driver, Chinatown, and Drive

Works Cited:

Bansal, Vinita. “How To Opt Out Of The Drama Triangle And Take Responsibility.” Tech Tello, 23 April 2020,

www.techtello.com/how-to-opt-out-of-the-drama-triangle/

Ebert, Roger. “An Interview with Martin Scorsese and Paul Schrader.” Scorsese, edited by Roger Ebert, The University of Chicago Press, 2008, pp. 42-47.

Wilkerson, Isabel. Caste: The Origins of Our Discontent. Penguin Random House, 2020.

![I Don’t Feel at Home in This World Anymore [2017]: Sundance Film Festival Review](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/I-dont-feel-at-home-in-this-world-anymore-1-768x489.jpg)