Gulzar’s “Ijaazat” (1987)—based on a story by Subodh Ghosh—is a film I really like. Although it is not my favorite film directed by Gulzar, I have never attempted to critique it, either. I was pretty complacent in surrounding myself with people who, like me, felt the film swam against the tide of the established etiquette of relationships. That was until I met my friend. In the nascent stage of our friendship, I made him watch the film, hoping to mint a Gulzar lover and, by extension, a famous Hindi cinema enthusiast.

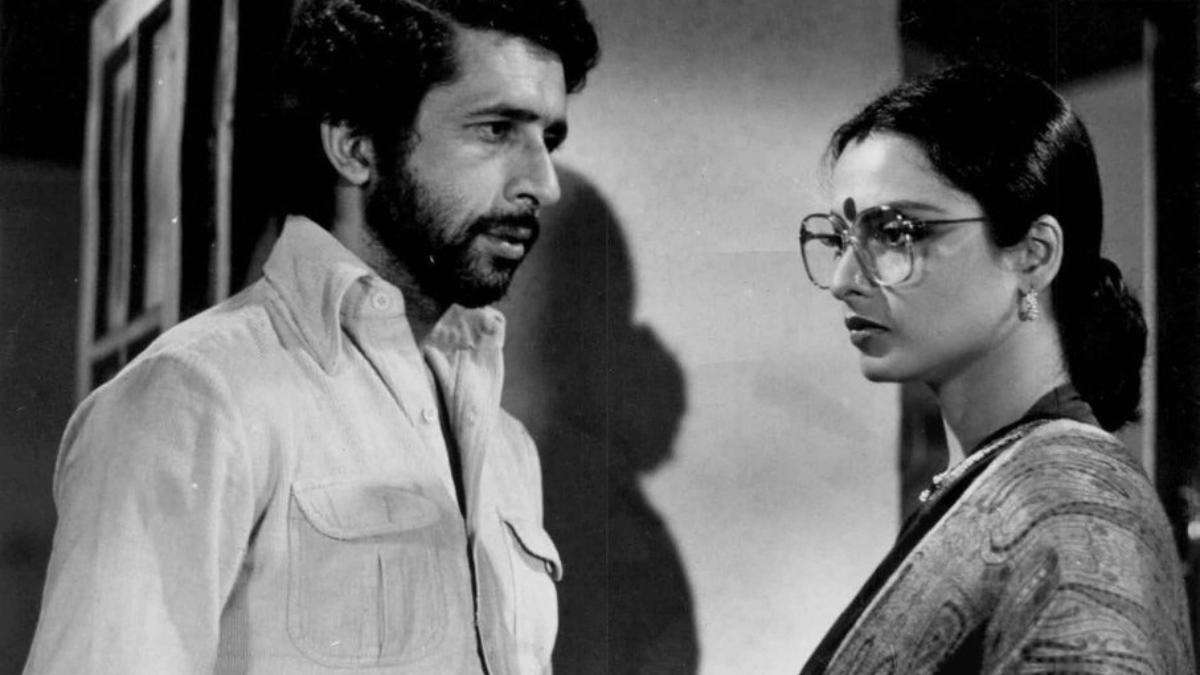

However, to my utter surprise, he hated it. This experience was utterly alien to me, and I did not know how to process it—a person who HATES “Ijaazat.” To my friend, “Ijaazat” — far from being devoid of a moral compass — seemed to be a reinforcement of the fact that it is a man’s world where one woman’s death keeps the other woman forever in guilt. He extended his criticism to include V. Shantaram‘s films “Kunku” (1937) and “Aadmi” (1939), where women not only splenetically denounce patriarchal dictum but also physically fight back against wayward men. In “Ijaazat,” the sight of Sudha (Rekha) touching Mahendra’s (Naseeruddin Shah) feet grated on him. I definitely disliked his opinion, but I knew I made a friend for life.

Although I would certainly have been happy to have a yes-man who liked “Ijaazat” as much as I liked it, the importance of having a friendship with someone not very susceptible to the idea of letting the other person decide the terms of one’s life was not lost on me — something which I secretly felt Mahendra largely lacked. And that is where I think the brief presence of Sudha’s husband (Shashi Kapoor) in the plot takes the cue. It is easy to sympathize with Mahendra. “Ijaazat” is, after all, no simple movie, and it is enduring status as a classic is perhaps due to its complexity: a man meets his divorced ex-wife at a waiting room of a railway station and traversing the initial discomfort, they reminisce about the good and the ugly aspects of their marital bond.

Before marrying Sudha, Mahendra had a romantic relationship with the effervescent Maya (Anuradha Patel). However, he has also vowed to marry Sudha. Mahendra’s reluctance to admit his relationship with Maya on the one hand and his inability to decline his marriage with Sudha on the other turns out to be an emotional quagmire for him. He eventually marries Sudha but remains faithful to Maya.

Although seemingly unperturbed in the beginning, Sudha soon starts feeling afflicted by the relationship between Mahendra and Maya. Eventually, realizing that the marriage is going nowhere, Sudha has to leave, and, unbeknownst to Sudha, Maya too dies, leaving Mahendra alone. Just when we, perhaps Mahendra too, expect Mahendra and Sudha to reconcile, a man barges into the waiting room looking for Sudha. All expectations are upended as we realize Sudha has remarried.

The singular act of Sudha’s husband barging through the door of the railway station’s waiting room delineates him as a character, bringing movement both to the story and Sudha’s life. He starts talking at length about how he spent the whole night being anxious about Sudha’s condition. He talks so much that he runs out of breath. However, it would have been one thing just to say that he cares and leave the words dangling. What we see as the case here with Sudha’s husband is the deliberate attempt to act upon his words.

Sudha asks her husband, “What was the need to come here and get me?” to which he replies endearingly, “You’re right! What was the need? I would have anyway sat there and spent the night smoking away in anxiety.” This exchange acts as a prompt to call into mind a similar instance when Sudha and Mahendra were married, previously shown in the narrative as a flashback.

When they were married, Sudha once broached the topic of going back to Panchgani to spend some time with her mother, and it was Mahendra who proposed that he would fetch her despite Sudha’s humble and outward protest. However, even after igniting the hopes, Mahendra failed to act on his promise and instead rekindled his relationship with Maya (Anuradha Patel) in Sudha’s absence. The husband’s movement, determination, and efforts place him against the inertia of Mahendra.

What Mahendra lacks, he never manages to make up for. However, what he lacks, Sudha has in abundance. The arrival of Sudha’s husband at the end reveals that that inexplicable quality in Sudha is finally reciprocated. Throughout the film, we see Sudha as a figure taking care of Mahendra. With her panic-stricken yet jolly husband, what Sudha only received in crumbs from Mahendra is doled out to her even without her asking for it. The scheme of things—Sudha’s habit of caring for Mahendra and keeping a matchbox with her—finally makes sense and finds a proper expression. Perhaps her husband does not let her reject the habits, albeit unknowingly. She does not need to reject them because the old habits perfectly fit her husband.

The women in the film are not competitors, vying for the attention of a lover at the center and indulging in a cataclysmic rivalry, as sojourners who are well aware of the transience of their presence in their man’s life and want to love him the best their personalities would allow them. The conflicting pulls of love from both sides never evoke a desire to prefer one woman over the other. Nonetheless, the same cannot be said about men. The fascination and impact of Sudha’s husband lie in the fact that he is not pitted against Mahendra. However, despite not being pitted against each other, a preference is surreptitiously laid out.

The introduction of Sudha’s husband somehow feels like an apt but subtle admonishment to Mahendra, whose beleaguered state is his own doing, his own inaction, and his non-intervention in his own life. In fact, Mahendra’s indecisiveness leads him to veer easily, which further pushes the women to the brink, where a bitter feeling of rivalry feels like the only feasible outcome. But just when we expect full-blown strife, the women turn more sympathetic towards each other ironically – that the women never follow Mahendra’s lead and fall into that cycle, albeit it is their own choice.

Upon taking his wife’s cue when Sudha’s husband learns that the stranger is indeed Mahendra, the ensuing shot-counter shot exchange between both the men is filled with a certain gentleness. It is evident that Sudha’s husband possesses a ready enough sympathy for Mahendra. In the end, he puts his arm around her and then walks away, leaving the old lovers alone, displaying a sense of reliability and understanding.

Sudha’s husband is not a dramatic vessel of Sudha’s revenge against Mahendra. Neither is he used as a device to incite feelings of jealousy in Mahendra, as is the norm usually with the introduction of a third person in love stories. He is just there—talking fast, gasping for breaths, caring for his wife, and losing his sleep for his wife’s well-being. This time, Sudha finds a companion in someone who would not succumb to passivity and would not wait for things to happen. His singular presence, devoid of pomposity, makes his impact so palpable.

![This Is Not Berlin [2019]: ‘Tribeca’ Review: The Outsiders](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/this-is-not-berlin-1-768x385.jpg)