Few filmmakers in Indian cinema have engaged with silence, spirituality, and guilt as hauntingly as G. Aravindan. A maverick of the Malayalam New Wave, Aravindan was less interested in storytelling than in what lay between stories, the invisible tensions, buried emotions, and unresolved desires that shape human experience. And G. Aravindan’s “Chidambaram” (1985) stands as one of the most profound and philosophically resonant films to emerge from Indian parallel cinema.

Based on a short story by C.V. Sreeraman, the film traces the tragic entanglements of three lives – Shankaran, Muniyandi, and Sivakami – against the quiet, unassuming backdrop of a government cattle farm located at the Kerala-Tamil Nadu border.

But “Chidambaram” is no ordinary tale of betrayal or infidelity. It is a deeply psychological and spiritual inquiry into human frailty, guilt, and the elusive possibility of redemption. While its surface narrative appears simple and spare, the film opens up to multiple interpretative layers – mythological, ethical, gendered, and existential – that position it as one of the most significant cinematic meditations on the human condition in Indian film history.

Winner of the National Award for Best Feature Film, “Chidambaram” marked a crucial moment in Malayalam cinema’s alternative tradition, where visual storytelling was elevated into spiritual reflection, and everyday gestures were invested with metaphysical significance.

Aravindan, a self-taught artist and musician, never subscribed to the melodramatic or expository tendencies of mainstream Indian cinema. Rather, his films are marked by what might be termed an “aesthetic of silence”, a commitment to suggestion rather than assertion, atmosphere rather than action, and introspection rather than spectacle. In “Chidambaram,” this aesthetic becomes particularly effective in articulating the burden of guilt and the impossible desire for absolution.

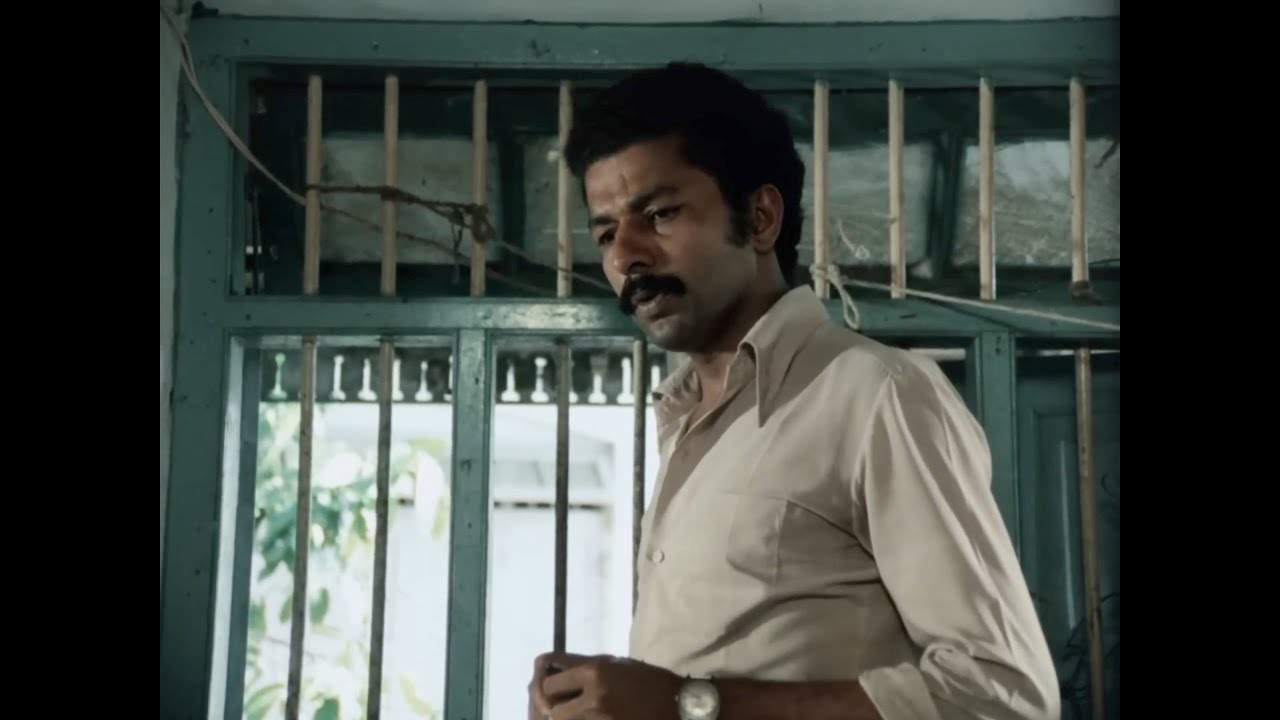

The narrative centres on Shankaran (Bharath Gopy), a solitary and reflective administrative officer, who begins to develop a quiet fascination, one that borders on obsession, for Sivakami (Smita Patil), the young wife of Muniyaandi (Sreenivasan), a devout and morally upright Tamil herdsman. When this fascination slips into an act of betrayal, it leads to Muniyandi’s suicide, setting Shankaran on a journey of psychic disintegration and eventual retreat to the sacred town of Chidambaram.

While much of Indian cinema treats guilt as a moral problem to be resolved through punishment or reconciliation, Aravindan treats it as an existential rupture, a trauma that fragments subjectivity and dislodges the self from social time.

This article examines “Chidambaram” through a triadic framework: first, by analysing its thematic preoccupation with guilt, transgression, and moral reckoning; second, by probing the film’s complex gender dynamics and its subtle critique of patriarchal codes; and third, by unpacking its distinct cinematic form, its visual and sonic grammar, which fuses realism with metaphysical introspection, marked by long takes, haunting silences, symbolic framing, and a soundscape that reflects psychological turbulence.

By drawing a comparative parallel between Shankaran and Dostoevsky’s Raskolnikov from “Crime and Punishment,” the article also explores the philosophical and literary echoes that inform Aravindan’s cinematic imagination.

Also Read: Food and Gender through the Lens of Hindi Cinema

In analyzing “Chidambaram,” we encounter a film that transcends the bounds of narrative to become a meditative exploration of betrayal, guilt, and spiritual unease. It does not simply recount a tale of transgression but compels us to confront the moral tremors embedded in the fabric of ordinary lives. Seamlessly merging myth with modernity, theology with psychology, and landscape with emotion, “Chidambaram” resists facile moral judgment even as it stages a profound ethical rupture. Aravindan employs cinema not as a vehicle for entertainment but as a contemplative medium of revelation.

By situating “Chidambaram” within the lineage of Indian art cinema while also engaging with global discourses on gender, guilt, and transcendence, this article seeks to unpack the film’s resonant silences and its open-ended, deeply human confrontation with the fragility of moral existence.

Between Fields and Forests: Narrative Overview

At first glance, “Chidambaram” unfolds like a minimalist pastoral drama, grounded in the slow rhythms of rural life and the apparent simplicity of human relationships. Set amidst the misty hills and forested pastures along the Kerala-Tamil Nadu border, the film’s setting is not merely geographic, but symbolic, a liminal space where boundaries of morality, desire, and identity are blurred. The narrative revolves around three central figures: Shankaran, the newly appointed farm overseer; Muniyandi, a Tamil cowherd and devout man; and Sivakami, Muniyandi’s young bride, whose quiet presence disrupts the fragile equilibrium of this isolated microcosm.

When Shankaran arrives at the remote cattle farm, he is portrayed as a man of few words – solitary, introspective, and somewhat aloof. Though urban in manner and educated in disposition, he displays an unforced empathy toward the farm workers, especially Muniyandi.

The film invests significant screen time in establishing the pastoral atmosphere: the slow-paced routines of animal care, the unhurried chatter among workers, and the lush green expanses of land create a cinematic rhythm that mimics the cadence of agrarian life. These opening segments are deceptively serene, creating a visual and emotional canvas onto which the later rupture will be starkly etched.

Muniyandi is the moral opposite of Shankaran, deeply religious, rooted in traditional values, and devoted to his work. When Muniyandi brings his wife Sivakami to live with him on the farm, the narrative undergoes a subtle shift. Sivakami’s introduction is quiet but magnetic. She is not a disruptive force in any overt sense; rather, her presence unsettles by contrast. Her youth, beauty, and silence evoke curiosity and perhaps a suppressed longing in Shankaran, whose solitary life has long been devoid of intimacy or emotional warmth.

Aravindan stages this shift not through dramatic declarations but through glances, gestures, and spatial arrangements. A single lingering shot of Shankaran observing Sivakami from a distance is enough to signal the beginning of internal upheaval.

What begins as a triangle of companionship soon deteriorates into a tangle of unspoken desires and moral ambiguity. Shankaran’s fascination with Sivakami is subtle at first, expressed through small acts of care, moments of silent observation, or awkward encounters, but it begins to take on a darker, transgressive hue.

The film is careful not to sensationalise the eventual act of betrayal. There is no melodramatic confrontation, no overt seduction; instead, the emotional and ethical tension builds quietly until it breaks. The viewer is left to infer the nature and extent of the intimacy between Shankaran and Sivakami. Aravindan’s refusal to depict the betrayal in explicit terms reflects his trust in the viewer’s moral imagination and his aesthetic commitment to restraint.

Muniyandi’s discovery of the betrayal precipitates the film’s most harrowing turn. His suicide, once again not depicted directly but implied through mood, reaction, and absence, serves as a moral rupture in the filmic world.

In the immediate aftermath, the cattle farm loses its previous harmony. The narrative no longer returns to the patterns of rural life; instead, it follows Shankaran’s interior collapse. The camera now detaches from pastoral serenity and begins to mirror Shankaran’s psychological fragmentation. The forest, which had previously framed the film’s tranquility, becomes a space of disorientation and guilt. Mist, darkness, and foliage envelop Shankaran as he flees, both physically from the farm and emotionally from himself.

This transition from field to forest is crucial. The open pastures had represented a world of order, community, and temporal regularity; the forest, in contrast, stands for chaos, introspection, and spiritual crisis. As Shankaran descends deeper into guilt and alienation, the film’s visual grammar follows suit: camera movements become more fluid but less stable, compositions become more abstract, and sound becomes a medium of psychological dissonance. The shift from community to solitude, from structure to dispersal, is not just geographical but existential.

The latter half of the film follows Shankaran as he drifts through various spaces, rural inns, pilgrim rest houses, forested paths, and finally the temple town of Chidambaram. These journeys are rendered in elliptical sequences that mirror his loss of narrative continuity. He is no longer the agent of his story but its haunted subject. His attempts to drown guilt in alcohol, prayer, and movement reflect the psychological desperation of a man who seeks redemption but cannot articulate what he needs to be redeemed from.

By the time Shankaran reaches Chidambaram, he is stripped of all external identities. There is no formal punishment, no social trial, no confrontation with Sivakami. Instead, there is only silence, ritual, and the ambiguous possibility of transcendence. In the temple, surrounded by the stillness of devotion and the grandeur of architecture, Shankaran becomes one with the anonymous mass of pilgrims, his individual guilt dissolving into the cosmic choreography of spiritual longing.

The final image of the film, a rising crane shot that follows the temple wall upward into the open sky, is at once sublime and unresolved. It resists closure, offering instead a vertical escape from narrative finality. The title “Chidambaram,” referring to the temple town but also to the metaphysical concept of “Chidambara Rahasya” (the hidden truth or the divine mystery of consciousness), gestures toward the film’s philosophical horizon. It suggests that human suffering, like divine absence, may remain forever inscrutable.

Also Read: Analysing the ‘New’ in Malayalam’s New-Generation Buddy Movies

Thus, what begins as a realistic portrayal of rural life evolves into a philosophical journey through guilt, alienation, and the search for grace. The film’s narrative structure mimics this movement, from the material to the spiritual, from the visible to the ineffable, from the literal to the symbolic. By the end, “Chidambaram” has transformed its sparse story into a meditation on the mystery of human conduct and the enigma of moral reckoning.

Mapping Desire and Disruption: Gender and Moral Tensions

While “Chidambaram” may initially appear to be a moral drama centered on male guilt and redemption, a closer reading reveals that its emotional architecture is profoundly shaped by gendered dynamics and the disruptive potential of female presence within a patriarchal world. The film critiques the very gender codes that drive the narrative: the expectation of female chastity, the idealisation of male morality, and the double standards of transgression.

The arrival of Sivakami into the closed, male-dominated space of the cattle farm acts as a catalyst—not because she is inherently transgressive, but because her mere presence exposes the fragility of masculine self-control and the hypocrisies embedded in moral codes. Her body becomes a surface upon which the desires, anxieties, and moral contradictions of the male characters are projected.

Sivakami is introduced not through dialogue, but through gesture, movement, and atmosphere. She is quiet, observant, and largely unvoiced throughout the film. In many ways, she embodies the archetype of the “silent woman” in Indian cinema, an idealized figure of passivity and moral purity. However, Aravindan neither romanticises nor vilifies her. Instead, he complicates this figure by allowing her silence to become a space of ambiguity rather than submission. Her role in the film is central yet elusive: she is the emotional core of the crisis, but her subjectivity remains largely inaccessible, refused both by the social world around her and by the cinematic gaze itself.

In this sense, “Chidambaram” stages a subtle critique of the patriarchal order. Both Muniyandi and Shankaran, though different in temperament and class, are bound by masculine codes of control and propriety. Muniyandi’s love for Sivakami is sincere, but it is filtered through religious dogma and possessiveness. He treats her with kindness, but also with a moral rigidity that leaves little room for mutual emotional negotiation.

Shankaran, in contrast, intellectualises his feelings. He observes Sivakami from a distance, projecting onto her his own loneliness and longing, never truly encountering her as an equal subject. When desire overtakes restraint, it is Shankaran, not Sivakami, who crosses an ethical line, yet the consequences fall upon all three characters, with Sivakami’s fate left in silence.

Aravindan’s treatment of this triangulated dynamic avoids the tropes of melodrama or blame. Instead, the film investigates how gendered structures of desire are mediated by silence, power, and moral perception. The fact that Sivakami never speaks about her experience, neither to Muniyandi nor to Shankaran, raises unsettling questions. Was her relationship with Shankaran consensual? Was it coerced? Was it emotional, physical, or merely an imagined intimacy from Shankaran’s side? Aravindan deliberately refuses to clarify. This ambiguity is not a narrative oversight but a thematic decision: it reflects the historical and cultural silencing of women in patriarchal moral narratives. In a traditional social order, the woman’s voice is not only unheard, it is unasked for.

Here, Laura Mulvey’s seminal theory of the male gaze becomes useful. In her 1975 essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” Mulvey argues that mainstream cinema constructs women as passive objects of male desire, with the camera functioning as an extension of male fantasy.

While “Chidambaram” does centre male perspectives, Aravindan carefully subverts the gaze. The camera never ogles Sivakami, or indulges in voyeuristic framing; instead, it watches Shankaran watching her. His longing is visible, but the film does not encourage identification with it. We do not see Sivakami as he sees her, we see him seeing. This doubling of the gaze introduces critical distance, rendering his desire problematic rather than seductive.

Moreover, the film’s refusal to eroticize the female body sets it apart from both commercial and arthouse Indian cinema of the period. Sivakami is not sexualised through costume, framing, or mise-en-scène. Her dignity is preserved even as she becomes entangled in a narrative of moral collapse. This restraint adds to the tragedy: she is burdened with symbolic weight, yet denied narrative agency. Her disappearance after Muniyandi’s death, a disappearance that is neither mourned nor resolved, highlights the gendered erasure that often follows women cast in the role of “disruptors” in patriarchal societies.

In one particularly telling scene, Shankaran witnesses a woman being excluded from participating in temple rituals, her role deemed inappropriate within the gendered framework of religious orthodoxy. This moment, quiet and observational, encapsulates the film’s broader critique of gender roles. It mirrors Sivakami’s own fate: seen, desired, judged, and ultimately silenced by institutions of masculinity, religion, and morality. Aravindan offers no explicit commentary here, but the resonance is unmistakable.

Ultimately, “Chidambaram” presents gender not as a thematic afterthought but as a structuring tension that shapes the film’s emotional and ethical terrain. The female presence in the film is not simply a narrative function or romantic interest; it is the axis around which the male characters’ identities unravel. In mapping desire and its consequences, Aravindan reveals how patriarchal ideologies not only victimize women but also corrode the moral fabric of men. In this way, “Chidambaram” becomes an elegy for the failure of ethical masculinity, a story in which love becomes guilt, morality becomes burden, and silence becomes the only honest response to the tragedy of human relationships.

Guilt, Flight, and Redemption: The Dostoevskian Parallel

At the heart of “Chidambaram” lies a profound moral and spiritual inquiry: what happens to the human self after it commits a transgression that cannot be undone? How does one live with guilt that has no material remedy and no witness other than the conscience? In exploring this question, G. Aravindan crafts Shankaran not merely as a character in crisis but as a cinematic embodiment of existential guilt, tormented, fractured, and adrift. His internal conflict resonates deeply with the psychological and philosophical contours of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s protagonist Raskolnikov from “Crime and Punishment” (1866), creating a compelling intertextual bridge between Malayalam cinema and Russian literary modernism.

Must Read: 15 Great Malayalam Movies to Stream on Prime Video

Raskolnikov, a former student in St. Petersburg, commits a double murder driven by a warped philosophical rationale, believing himself to be beyond conventional morality. What follows is not a chase by the law, but a relentless pursuit by his own conscience. His descent into illness, delirium, and psychological fragmentation foregrounds Dostoevsky’s central concern: the unbearable weight of guilt and the tortured path to redemption.

Although Shankaran does not kill anyone and certainly does not premeditate his wrongdoing, he finds himself in a similar moral abyss. His emotional entanglement with Sivakami, culminating in an undefined but clearly transgressive act, leads indirectly to Muniyandi’s death. The enormity of that consequence, unintended yet irrevocable, unmoors Shankaran from his identity, his community, and his very sense of self.

The crucial point of comparison between Shankaran and Raskolnikov lies in their isolation after the transgression. Both characters undergo a process of psychic exile, alienated from society and estranged from themselves. They are not punished by external forces; their torment is internal, existential. In this sense, Aravindan’s narrative approach mirrors Dostoevsky’s: the “punishment” is psychological, not juridical. Law is not the ultimate arbiter, it is conscience.

Aravindan visually manifests this moral disintegration through a shift in cinematic space. After Muniyandi’s suicide, Shankaran leaves the cattle farm and begins wandering, first into the forest and then across unnamed rural and semi-urban spaces. These sequences, composed with long tracking shots, suggest a man unmoored from any sense of place or purpose.

The forest is not merely a background but a metaphor for moral confusion. As he moves through mist and foliage, enveloped in silence and often framed in isolation, Shankaran becomes a ghost of himself. The narrative becomes elliptical; time loses continuity. Just as Raskolnikov’s fevered state blurs reality and hallucination, Shankaran too begins to drift between the material and the metaphysical.

Both men also attempt various forms of self-medication. Raskolnikov turns to abstract rationalisation, then self-loathing, before reluctantly accepting the need for confession and penance. Shankaran turns to alcohol, disavowal, and spiritual tourism, seeking relief in movement, but finding no respite from his own mind.

Aravindan’s use of silence becomes especially powerful here. There is no soliloquy, no anguished confession. Guilt is not spoken; it is suffered. In one key scene, Shankaran sits alone in a roadside rest house, barely visible in the gloom, his face half-lit by a flickering lamp. The stillness of the frame becomes an image of spiritual paralysis. Like Raskolnikov, he is trapped in a liminal zone, between acknowledgment and denial, between punishment and salvation.

Yet, there is a crucial cultural difference in how these two journeys toward redemption are conceived. In “Crime and Punishment,” redemption comes through Christian confession and the acceptance of Christ’s love, culminating in Raskolnikov’s symbolic resurrection in Siberia. “Chidambaram,” however, operates within a Hindu metaphysical framework, wherein karma, dharma, and atonement take less linear forms. Shankaran’s arrival in the temple town of Chidambaram is not a confession, nor is it a return to society. It is a movement inward, a silent submission to something larger than law or morality.

Chidambaram, the temple town, is rich with philosophical connotations. In Shaivite cosmology, it is the sacred site where Lord Shiva performs the Ananda Tandava, the cosmic dance of creation, preservation, and destruction. The Chidambara Rahasya, or “secret of Chidambaram,” refers to the idea that the divine is present even in apparent emptiness, that truth lies not in what is seen but in what is intuited. Aravindan’s choice of this setting is not incidental. The final sequences of the film unfold within the visual and symbolic architecture of this sacred geography. Here, the boundaries between the personal and the cosmic begin to dissolve.

Shankaran does not speak in Chidambaram. He does not seek forgiveness from Sivakami, nor is he confronted by anyone from his past. Redemption, if it arrives, is not explicit but atmospheric. In one scene, he watches a temple ritual in silence, his expression unreadable, his presence unnoticed. The temple walls, the ritual chants, and the solemn stillness of the setting offer not resolution but resonance. The final upward crane shot, lifting from the temple wall toward an open sky, is a visual metaphor for transcendence, but it is also enigmatic. Has Shankaran been forgiven? Has he forgiven himself? Aravindan refuses to answer.

This refusal to moralise or resolve the narrative is what aligns Aravindan most closely with Dostoevsky, not in religious doctrine, but in philosophical ambiguity. Both artists are interested in the depths of conscience, in the fractured self who seeks truth without certainty. If Raskolnikov finds peace in confession, Shankaran finds only a kind of contemplative anonymity.

In the end, both characters are redeemed not through restitution, but through endurance. They are not heroes; they are men broken by desire and salvaged by the mystery of existence. Through the figure of Shankaran, Aravindan explores the silent torment of a man who cannot articulate his fall. His punishment is not delivered but lived. And in aligning this journey with the mythic space of Chidambaram, the film raises a timeless question: can one truly be freed from guilt, or does redemption merely consist in learning how to carry it with grace?

Myth, Metaphor, and the Mystery of the Title

Aravindan’s choice to title his film “Chidambaram” is far from arbitrary. At first glance, the narrative bears no overt connection to the Tamil temple town of the same name for most of its duration. The setting is not introduced until the final act, and none of the characters belong to or speak of the place until Shankaran’s solitary arrival there.

Yet, as the film slowly unfolds and its philosophical undertow deepens, Chidambaram emerges not merely as a geographical location but as a layered symbol – mythic, metaphoric, and metaphysical. The title becomes a cipher for the film’s central concerns: the invisible dimensions of guilt, the sacred possibilities of atonement, and the silent architecture of inner transformation.

To understand the significance of the title, one must first turn to the religious and cultural meanings of Chidambaram itself. Located in Tamil Nadu, the town is home to the famous Nataraja Temple, a rare shrine where Lord Shiva is worshipped in his cosmic dancing form – Nataraja, the Lord of the Dance. The dance Shiva performs here, the Ananda Tandava, is not a theatrical gesture but a cosmic act: the dance of creation, preservation, destruction, concealment, and grace.

The temple’s central sanctum enshrines not just the idol of Nataraja, but also an empty space symbolizing the Chidambara Rahasya, “the secret of Chidambaram.” This secret is the formless, attribute-less Brahman, the divine void. Here, divinity is not contained in form, but in absence. Truth is not what is seen, but what is sensed beyond visibility.

Related Read: The 10 Best Malayalam Movies Of 2024

This theological premise becomes the key metaphor through which Aravindan frames the film’s final movement. Like the concealed presence at the heart of the temple, the meaning of the film is constructed around silences, absences, and the unsaid. Shankaran’s journey to Chidambaram is not motivated by religion in any conventional sense—he is not on a pilgrimage, nor is he seeking formal absolution.

Instead, the town serves as a mythic end-point to a formless inner journey, a space where silence might offer what language and action cannot: a reckoning with the self. In this way, “Chidambaram” becomes a metaphor for the possibility of encountering truth in emptiness, resolution in ambiguity.

Aravindan’s aesthetic language mirrors this metaphysical tension. Throughout the film, the camera resists dramatic gestures. Instead of showing emotion, it reveals space. Landscapes are filmed with patient attention; human figures often occupy the margins of the frame. There is a deliberate refusal to impose narrative clarity.

This withholding becomes an ethical and metaphoric choice. Like the curtain that conceals the divine in the Chidambaram sanctum, the film too veils its meanings, offering glimpses but never assertions. The audience, like Shankaran, is invited to experience rather than decode, to dwell in a space of moral and spiritual ambiguity.

The mystery of the title also speaks to Aravindan’s larger project of fusing the sacred with the secular, the mythical with the modern. “Chidambaram” is not a mythological film in genre, yet it invokes mythology through structure and atmosphere. Shankaran’s movement from a pastoral space to a temple town echoes a symbolic arc: from innocence to fall, from guilt to potential redemption. The landscapes he crosses – field, forest, roadside, town – resemble a kind of internal cartography, a pilgrimage without rituals. In this sense, Aravindan reshapes myth into a metaphor for moral reckoning. Chidambaram is not a destination on a map but a state of being, a stillness in which one confronts the divine within, and perhaps, forgives the self.

Moreover, the title resists closure. It raises questions rather than resolves them. Why Chidambaram? Why does the film end in a space that is as much symbolic as physical? The answer may lie in Aravindan’s own spiritual sensibility, a sensibility deeply influenced by Indian philosophical traditions, but equally shaped by modernist abstraction. In “Chidambaram,” myth is not used to confirm belief, but to evoke mystery.

The film does not moralize; it meditates. The divine is not shown; it is implied. And the title, like the film itself, remains a silent gesture toward the ineffable. Thus, Chidambaram is not only a place, but a principle,a metaphor for the unknowable, the unnamable secret that lies at the heart of being. In titling his film after it, Aravindan makes a radical aesthetic and philosophical move: he invites the viewer not to interpret, but to contemplate; not to understand, but to witness.

The Cinematic Language of Remorse

Aravindan’s “Chidambaram” communicates remorse not through dramatic confessions or heightened emotional outbursts, but through a nuanced orchestration of silence, mise-en-scène, and movement. The film’s visual style mirrors the inner landscapes of its characters, particularly Shankaran, whose moral disintegration is rendered in slow, contemplative tracking shots, sparse dialogue, and expressive use of natural light. Guilt becomes a spatial condition, an atmosphere that envelops the frame, as much as a psychological burden.

The camera lingers on empty spaces, receding figures, and dense forest paths, crafting a meditative visual rhythm that mirrors the protagonist’s emotional detachment and inner turmoil. This minimalism is never empty; rather, it is weighted with unspoken grief and existential dislocation. The long takes and ambient soundscapes slow time, forcing the viewer to dwell in moments of discomfort and introspection, just as Shankaran must.

Aravindan’s refusal to show key events directly, such as the seduction, the suicide, or moments of confrontation, shifts the focus from spectacle to consequence. What matters is not what is seen, but what is felt in its absence. In this way, the cinematic language of “Chidambaram” becomes a vessel for remorse itself: diffused, persistent, and inescapable.

The film’s soundscape is equally vital. G. Devarajan’s music is used sparingly but potently. Folk songs accompany pastoral scenes, creating a nostalgic innocence around Sivakami. At moments of tension, the music erupts into dissonant swells, emotional outbursts that compensate for the characters’ repression. When remorse sets in, music recedes again, mirroring the cycle of suffering and reflection. Silence, too, is calibrated. The absence of speech after Muniyandi’s death is not mute grief but judgment. It is in this lacuna of language that the audience feels the full weight of moral consequence. Aravindan trusts the viewer to listen beyond words.

Open Endings, Unfinished Reckonings

“Chidambaram” ends not with redemption but with ambiguity. The crane shot that lifts from Shankaran toward the temple sky is both literal and metaphysical, a movement outward, upward, unresolved. It is Aravindan’s quiet refusal to close the moral question, his invitation to the viewer to inhabit that space of silence and introspection. In a cinematic landscape often saturated with loud declarations and moral binaries, “Chidambaram” offers a rare cinematic ethics. It proposes that guilt is not only psychological but spiritual, that redemption lies not in action but in awareness, and that human relationships, especially those marked by gender asymmetry, are never fully legible.

Aravindan’s cinema resists commodification. It asks for patience, for moral engagement, for philosophical reflection. In “Chidambaram,” the personal and the metaphysical collapse into each other, creating a film that is not just watched but endured, not just interpreted but felt. As India continues to grapple with questions of gender justice, moral accountability, and the ethics of desire, Aravindan’s “Chidambaram” remains as urgent and as enigmatic as ever.

![Mahaan [2022] ‘Prime Video’ Review – Calling It ‘Ridiculous’ is an Understatement](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Mahaan-2022-768x432.jpg)

![Children of Hiroshima [1952] Review – A Poignant Account on the Horrors Endured in the Aftermath of A-Bomb](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Children-of-Hiroshima-1952-768x548.jpg)