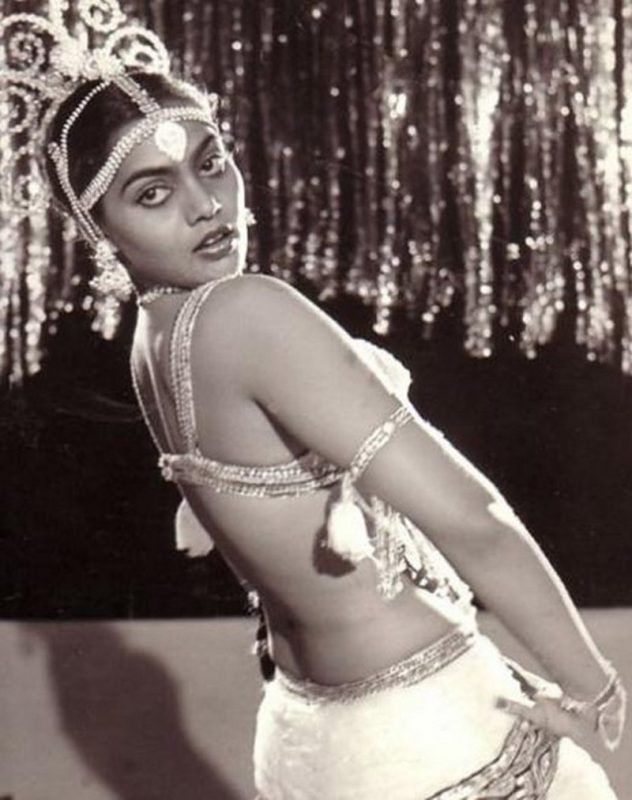

In the crowded theatres of the 1980s, when audiences sat on wooden benches or the dusty floors of single-screen halls, a certain electricity ran through the crowd whenever the name Silk Smitha appeared in the credits. Whistles, catcalls, claps, and knowing murmurs often drowned out the film’s opening lines. For working-class spectators in Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, and Karnataka, her arrival onscreen was a promise of spectacle. She was not just another actress squeezed into a supporting role or an “item number”; she was the event audiences waited for, the guarantee of their paisa vasool.

But Silk Smitha was more than just a crowd-puller. She was a cultural phenomenon that redefined how desire was performed, consumed, and policed in Indian cinema. She became one of India’s most popular sex symbols of the 1980s and early 1990s, as well as one of the most sought-after erotic actresses in South Indian cinema in the 1980s. Her career began with a small role in “Vandichakkaram” (1979), where she played a bar dancer named Silk.

The name stuck, fusing character and performer into a single identity, and soon “Silk” became shorthand for sensuality itself. Over the next decade and a half, she would appear in over 400 films across South Indian languages, her presence turning songs like “Nethu Rathiri Yamma” (“Sakalakala Vallavan,” 1982), “Mella Mella Ennai Thottu” (“Vaazhkai,” 1984), “Adiye Manam Nilluna” (“Neengal Kettavai,” 1984), “Thottukava” (“Subash Babu,” 1993), or “Ezhimala Poonchola” (“Spadikam,” 1995) into cultural landmarks.

Yet her phenomenon was defined as much by contradiction as by popularity. The same producers who depended on her screen presence dismissed her as vulgar; the same audiences who idolised her in darkened theatres would publicly disavow her in daylight. Silk Smitha came to embody what cultural theorists might call a “paradoxical star text”: she was indispensable to the economy of South Indian cinema, but denied legitimacy in the pantheon of respectable stardom.

Her persona also revealed deeper anxieties around class, caste, and gender. Dark-skinned and voluptuous, she disrupted entrenched ideals of fair-skinned, upper-caste heroines. Working-class audiences embraced her as one of their own, even as elite critics vilified her as a corrupting influence. In her, the anxieties of Indian modernity – sexual repression, moral conservatism, and aspiration for mobility – were played out in sharp relief.

Her tragic death by suicide in 1996, at the age of 35, only amplified her myth. Newspapers painted her as the archetypal fallen woman, consumed by excess and loneliness. But to remember Silk only through the lens of tragedy is to miss the magnitude of her cultural impact. She was not simply an erotic star, nor merely a victim of exploitation; she was a disruptive presence that changed how women’s bodies, sexuality, and stardom were negotiated in Indian cinema.

Silk Smitha was, and continues to be, a phenomenon, not because she fit into the narratives the industry created for her, but because she never quite did. To write about Silk Smitha is to navigate the multiple gazes – male, moral, feminist, nostalgic – that have shaped her afterlife.

Stardom And Desire: The Silk Spectacle

To understand Silk Smitha’s stardom is to understand the way cinema manufactures and mediates desire. From her breakthrough role in “Vandichakkaram” (1979), where she played a bar dancer christened Silk, her screen persona was marked by a boldness that South Indian cinema had rarely foregrounded in its women. While conventional heroines of the era – Sridevi, Radha, Ambika, or Sumalatha – were framed within the ideals of chastity, romantic innocence, or sacrificial womanhood, Silk entered the screen as pure provocation.

She crystallised her star persona playing the bold and seductive teacher opposite Kamal Haasan in “Moondram Pirai” (1982). Her numbers in “Sakalakala Vallavan” (1982) stand as a defining moment. The song “Nethu Rathiri Yamma” did not simply function as a diversion but became the film’s centrepiece, drawing crowds who came as much for her as for Kamal Haasan. Clad in glittering costumes, her eyes meeting the camera with unapologetic boldness, she inverted the language of the “demure heroine” and cemented her as the reigning queen of desire. The audience was not asked to desire her discreetly but to confront her sensuality directly.

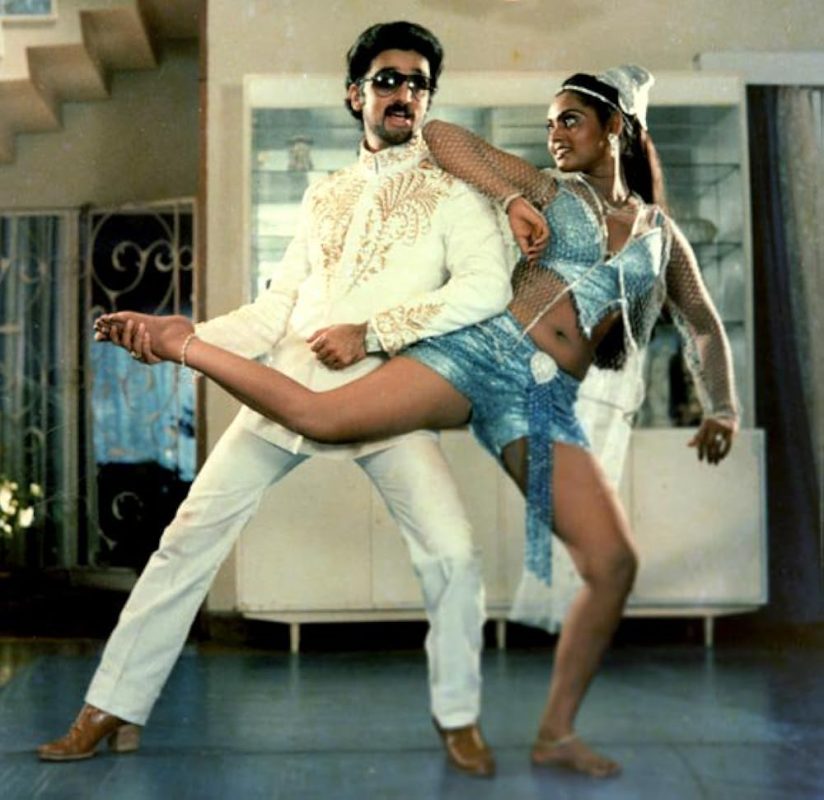

This effect was repeated across industries. In “Goonda” (1984), the rustic energy of “Gundalu Teesina” juxtaposed her earthy sensuality with Chiranjeevi’s rising charisma, helping cement his superstar status. In Malayalam cinema, her appearances in films like “Adharvam” (1989) and “Spadikam” (1995) became cultural shorthand for passion and intensity, often outshining the main narrative arcs. Each of these roles reaffirmed her as a figure who could guarantee box-office success.

But what set Silk apart from other “item dancers” or cabaret performers was the way she combined spectacle with presence. Her body was not merely displayed; it performed desire as a conscious act. The lingering camera shots, the exaggerated gestures, and the deliberate slowness of her movements communicated a kind of agency within the performance. She wasn’t passive, being looked at, she was looking back. Film theorists like Laura Mulvey, who described cinema’s “male gaze,” would find in Silk’s screen presence an ambivalence: yes, she was objectified, but she also unsettled the gaze by refusing to be merely ornamental.

This ambivalence explains the frenzy in theatres. Reports and anecdotes from the 1980s tell us of audiences erupting into applause, throwing coins at the screen, and demanding replays of her songs. For many working-class men, her presence embodied fantasies otherwise policed by conservative morality; for women, she sometimes represented an alternate femininity, brazen and unafraid, though also stigmatised.

Her stardom thus lay in creating what Richard Dyer calls the “structured polysemy” of the star image: multiple, sometimes contradictory meanings coexisting. To some, Silk Smitha was vulgarity incarnate; to others, she was power, desire, and escape from routine. In that plurality, her spectacle became a phenomenon, one that refused to be contained within the role of vamp, heroine, or supporting star.

Gender, Body, And Morality: Between Whistle And Whisper

Silk Smitha’s stardom was built on a paradox: she was at once indispensable to the commercial machinery of South Indian cinema and dismissed as a corrupting presence. Her body was the centrepiece of hundreds of films, yet it was rarely legitimised as art. Producers and distributors openly acknowledged that including a Silk Smitha song could guarantee box-office returns, and many films – even those frontlined by superstars – were marketed around her appearances. Still, she remained marked by stigma. While the heroine was elevated as the custodian of virtue, Silk was coded as the “other woman,” a figure of temptation against which chastity could be measured.

This contrast is particularly clear in “Moondram Pirai” (1982). The film paired Sridevi, whose character exudes innocence and childlike vulnerability, with Silk Smitha’s character, a schoolteacher whose every gesture is coded as predatory and overtly sexual. In the moral architecture of the film, Sridevi’s purity shines brighter because it is set against Silk’s exaggerated sensuality. The narrative uses her body as a moral boundary: to desire her is dangerous, to reject her is virtuous. Here, cinema used her body as a boundary marker, a cautionary figure against whom “good womanhood” could be defined.

More Related to Women in Films: The Return of ‘Chaotic Women’ in Indian Independent Cinema

Yet audiences responded differently from what the films intended. In theatres, her songs often became the high point of the screening. Whistles, applause, and showers of coins on the screen revealed an ecstatic embrace of her sexuality. Men in particular found in her performances a socially sanctioned outlet for desires otherwise repressed by conservative morality. For them, Silk’s on-screen persona collapsed the distance between cinema and fantasy: she was not the unattainable, idealised heroine, but an earthy, immediate figure of desire.

This double reception – celebration in the dark of the theatre, disavowal in the light of public discourse – exposes the deep contradictions of Indian society’s relationship with female sexuality. The same spectators who clapped and cheered in cinema halls often joined in moralistic condemnations of Silk as a “bad influence” on women. Female spectators, too, were caught in an ambivalence: some saw her as an embodiment of a forbidden freedom, while others internalised the discourse of shame attached to her.

The industry’s treatment of Silk reflected these moral anxieties. She was never offered the range of roles that went to her contemporaries, even though her screen presence was arguably stronger than many heroines. Instead, she was consistently typecast in roles that highlighted her body – dancers, vamps, mistresses, lonely widows – characters defined primarily through sexuality. Her talent as an actress, evident in films like “Layanam” (1990), where she played a complex, melancholic woman yearning for intimacy, was overlooked in favour of reinforcing her erotic type.

Thus, Silk Smitha became both spectacle and scapegoat. She embodied what audiences desired but could not admit to desiring. She gave shape to fantasies that society itself generated but projected onto her as an external “threat.” In this way, her body was made to bear the burden of morality, celebrated with whistles in the dark, whispered about with shame in the daylight.

The Politics Of Class And Caste: Desire And Discomfort

Behind the dazzling artifice of Silk Smitha’s screen persona lay the realities of class and caste politics that deeply shaped her career and reception. Born as Vadlapati Vijayalakshmi into a Telugu-speaking family of modest means in Eluru, Andhra Pradesh, in 1960, Silk came from a working-class and socially marginalised background. Her family’s poverty meant that her education was cut short, and she took up odd jobs before entering the world of cinema as a makeup artist’s assistant.

Her doorway into cinema was neither through elite grooming nor through industry connections but by way of menial jobs, persistence, and eventually finding a place in the world of make-up rooms and minor roles. This background would haunt her stardom, making her both indispensable and forever excluded from the “respectable” ranks of South Indian heroines.

The discomfort around Silk’s stardom was not just about her sexuality; it was also about who she was allowed to be within the hierarchical social order of Indian cinema. At a time when many heroines came from either upper-caste families or from relatively privileged, Anglo-educated, urban backgrounds, Silk’s rootedness in the rural and subaltern sphere marked her as “other.” Her body, darker and fuller compared to the fair, delicate archetype of the “ideal heroine,” was coded as earthy, raw, and uncontainable, qualities that both attracted mass audiences and triggered anxieties among the middle classes.

Her roles frequently mirrored this divide. In films like “Moondram Pirai” (1982) or “Goonda” (1984), she was positioned against the fair, morally sanctified heroine, a figure typically embodied by actresses like Sridevi or Radha. The heroine symbolised urban aspiration, refinement, and chastity; Silk embodied rusticity, carnality, and excess. In effect, the screen was staging a caste-coded dichotomy: the desirable yet disposable vamp versus the marriageable heroine. This was not accidental, it reflected and reinforced social structures in which women from marginalised backgrounds could be objects of desire but not subjects of respectability.

Audience reactions also reflected class contradictions. In working-class theatres, Silk’s songs were celebrated with abandon, her sensual dance moves in films like “Layanam” (1990) or “Goonda” (1984) sparked not shame but collective thrill. Yet among the upwardly mobile, English-educated classes, Silk was often dismissed as vulgar or “cheap.” What was pleasure for one group was pollution for another. Her stardom, therefore, revealed cinema’s role as a battleground where classed and caste-coded notions of taste, morality, and respectability played out.

Moreover, Silk herself often bore the stigma of being “inauthentic” to the heroine’s world. She was rarely given lead roles in mainstream productions, and when she did headline films, as in “Layanam” (1990) or “Miss Pamela” (1989), they were marketed as “soft-porn” or “B-grade” cinema, categories that simultaneously profited from her name while discrediting her artistry. This marginalisation was not simply aesthetic but structural, rooted in the inability of the industry to imagine a woman of her background and body type as a legitimate heroine.

Her career trajectory thus reveals how cinema encoded caste and class hierarchies on the female body. Silk was fetishised as the emblem of raw, lower-class sexuality but denied the symbolic capital of the “respectable” star. The tragic irony was that the very qualities that made her a beloved figure of mass desire also became the grounds for her exclusion from critical recognition and social acceptance.

In this sense, Silk Smitha was not only a victim of patriarchal morality but also of caste-class prejudice. Her body was not just sexualised – it was socially marked. To desire her was permissible, but to dignify her was not. This ambivalence, inscribed in both the films she acted in and the social commentaries that followed her career, underscores how caste and class shape the politics of desire in Indian cinema.

Agency And Exploitation: The Star Who Knew Her Worth

Silk Smitha’s career is often reduced to a story of exploitation, as though she were a passive object at the mercy of a voracious film industry. Certainly, she was typecast and overused by producers who saw in her body a formula for instant box office success. In countless films of the 1980s, a Silk Smitha number was inserted as a commercial guarantee, whether or not it bore relevance to the narrative. Yet, to see her only through this lens is to deny her the sharpness of her survival instincts and the courage with which she navigated a male-dominated, caste-stratified industry.

A school dropout who initially worked as a maid, Silk Smitha reinvented herself with astonishing clarity, cultivating an aura that was both provocative and self-assured. Anecdotes from film shoots recount how she was never shy about negotiating her remuneration, often demanding higher pay than many of her female contemporaries. In fact, by the mid-1980s, she was among the highest-paid actresses in South Indian cinema, reportedly charging more than established heroines for her appearances.

Silk knew her power: she could make or break a film. Her awareness of her own marketability was a form of agency rarely acknowledged in the stories told about her. In films like “Moondram Pirai” (1982), while the narrative revolved around Kamal Haasan and Sridevi, it was Silk’s cameo performance, her suggestive dance, that left a lasting impression. She knew that her presence could alter the mood of a film, sometimes even overshadowing the “main” heroine. Similarly, in Telugu thrillers like “Roshagadu” (1983) and “Gudachari No. 1” (1983), she was not simply ornamental; her roles carried hints of danger, intrigue, and independence.

Also Related to Female Agency: Why Women-Centric Films in Hindi Cinema are not Necessarily Feminist Films?

But agency coexisted uneasily with exploitation. The industry relentlessly pigeonholes her into the “vamp” slot, refusing her entry into “respectable” lead roles. Even when she attempted to break free by acting in more substantial parts, like in “Layanam” (1991), which explored female desire in ways unprecedented in Malayalam cinema, critics refused to take her seriously, branding her once again as scandalous. The line between Silk’s agency and the industry’s exploitation was constantly shifting: while she carved her own economic independence and aura of control, she also became a prisoner of the very image she had perfected.

Her life is thus emblematic of a larger paradox in cinema: the actress whose body became a site of commercial extraction also asserted herself as a labourer who knew her value and fought to be compensated for it. Silk Smitha was never just the “used woman” of industry lore; she was also the shrewd professional who understood that if her body was the spectacle, then it was hers to price. In this duality of power and precarity lies the enduring complexity of her stardom.

Representation And Legacy: The Tragedy Of Excess

Silk Smitha’s life and career are often narrated through the cautionary lens of “excess” – excessive sensuality, excessive consumption, excessive fame, and ultimately, the excessive loneliness that consumed her. This rhetoric of “too much” became central to her public image, as though her downfall were an inevitable punishment for daring to embody desires the society itself was obsessed with but refused to openly acknowledge.

On screen, Silk represented an uncontainable force of desire. She was loud, flamboyant, and unapologetically erotic in films where heroines were coded as docile, virtuous, and sacrificial. A typical scene from her career might show the contrast vividly: in “Moondru Mugam” (1982), Rajinikanth plays a righteous cop, and Silk appears in a bold cabaret number, a performance that electrifies audiences but is also carefully cordoned off from the “moral” universe of the narrative. She carried the burden of embodying “desire” so that the heroine could remain untouched by it. The tragedy is that cinema wanted her abundance but refused her legitimacy.

Her off-screen life was similarly interpreted through this discourse of excess. Media accounts spoke of her “lavish lifestyle,” “mysterious men,” and “failed investments.” These narratives overshadowed her struggles with isolation, financial precarity, and the exhaustion of constantly performing an image larger than life. By the early 1990s, as younger “glamour actresses” entered the industry, Silk was edged into obsolescence, her body no longer the marketable guarantee it once was. When she died in 1996, reportedly by suicide, newspapers sensationalised the event, framing her as the ultimate cautionary tale: a woman consumed by her own appetite for fame and desire.

But her legacy is more layered than this tragic reduction. For one, Silk Smitha redefined the vocabulary of female representation in South Indian cinema. She made visible the erotic charge that mainstream cinema simultaneously desired and disavowed. Without her, the vamp would have remained peripheral, a dancer in the background, a momentary distraction.

With Silk, the vamp became central, sometimes eclipsing the hero and heroine themselves. Her performances in films like “Goonda” (1984) with Chiranjeevi or “Sakalakala Vallavan” (1982) with Kamal Haasan demonstrate how her presence could dominate the screen, dictating audience attention and even driving box office success.

Her legacy also lingers in how subsequent generations of filmmakers, actors, and critics talk about her. Milan Luthria’s “The Dirty Picture” (2011), inspired by her life, tried to frame her as both victim and icon, “a woman who lived by her rules, but died by society’s judgment.” Though fictionalised, the film reignited public debates about her place in cinematic history. Meanwhile, younger actresses like Shakeela in the late ’90s inherited Silk’s space in the “erotic economy” of cinema, but never with the same combination of charisma, command, and cultural resonance.

The tragedy of Silk Smitha is not simply that she lived “too much,” but that Indian cinema and society refused to create a space where her excess could be honoured as artistry rather than condemned as immorality. She was punished not for failing to be a star, but for embodying a form of stardom that unsettled the patriarchal boundaries of respectability. Her legacy endures as a reminder that female desire in cinema, when given flesh, voice, and agency, remains a site of both fascination and fear.

Comparative And Interdisciplinary Angles: Between Helen And Sridevi

To understand Silk Smitha’s unique place in Indian cinema, it is illuminating to situate her between two other iconic figures of femininity and performance: Helen, the celebrated cabaret dancer of Hindi cinema, and Sridevi, the reigning star of South Indian and later pan-Indian cinema. The triangulation between these three figures reveals how the Indian film industry distributes desire, respectability, and artistry across women’s bodies, shaping careers in ways that are deeply coded by gender, class, and cultural anxieties.

Helen, in the 1960s and ’70s, was the quintessential vamp of Bollywood – exotic, Anglo-Indian, and cast as the other woman – who could shimmy in sequins and high heels while the heroine remained veiled in chastity. Her cabaret numbers like “Piya Tu Ab Toh Aaja” or “Mehbooba Mehbooba” epitomised a stylised, Westernised sexuality. Yet, Helen was rarely allowed to anchor a narrative. Her presence was strictly episodic, her desirability quarantined so that it would not contaminate the heroine’s moral universe.

Silk Smitha inherited this “vamp economy” but radically transformed it. Unlike Helen, whose glamour was coded as imported and cosmopolitan, Silk’s eroticism was grounded in the vernacular. Her dusky skin, voluptuous figure, and suggestive glances carried a distinctly regional aura. She belonged to the land and its sensual rhythms rather than to a nightclub in Bombay. Her sensuous songs were not just spectacles; they were integrated into the texture of Tamil and Telugu popular culture, spilling into everyday references and street slang. Unlike Helen’s “foreignness,” Silk’s sexuality was unsettling precisely because it felt so indigenous, so close to home.

In contrast, Sridevi, Silk’s contemporary and sometimes co-star, embodied the “ideal heroine.” In the same films where Silk dazzled with erotic cabarets, Sridevi appeared as the virtuous romantic lead – playful, comic, or tragic, but always within the frame of respectability. For instance, in “Moondram Pirai” (1982, later remade as “Sadma”), Sridevi’s performance as a woman regressed into childlike innocence drew critical acclaim for its pathos and artistry. Meanwhile, Silk’s performances were celebrated in the popular imagination but not accorded the same critical legitimacy.

What is striking is that audiences consumed both women in the same breath. They would whistle for Silk’s item numbers and weep for Sridevi’s tragic heroines. Cinema needed both – the seductive promise of the vamp and the safe comfort of the heroine – but it rewarded them differently. Sridevi ascended into the pantheon of “family-friendly” superstars, eventually crossing over into Hindi cinema as a national icon. Silk, despite her box-office pull, remained confined to the margins, her career circumscribed by moral suspicion.

An interdisciplinary lens drawing from film studies, gender theory, and cultural anthropology reveals the underlying dynamics here. Helen, as the exoticised “other,” and Sridevi, as the sanctified heroine, mapped the permissible boundaries of female performance in cinema. Silk Smitha disrupted these categories by collapsing the vamp and the heroine into one overwhelming persona. She was local, desirable, commanding and for that very reason, dangerous to patriarchal structures that preferred to keep women’s roles neatly separated.

Explore More: 10 Best Movies That Poignantly Explore Girlhood

This comparative framing also exposes how cinema is a cultural laboratory where the politics of gender, class, caste, and desire play out. Helen’s “foreign” cabarets, Sridevi’s “respectable” heroines, and Silk’s “vernacular eroticism” illustrate three different negotiations of female stardom in India. Together, they highlight why Silk Smitha’s legacy is so singular: she was neither a detachable spectacle nor a morally sanctified heroine, but something more unruly, more disruptive, a reminder that desire, when made flesh in a woman’s body, can neither be easily contained nor comfortably celebrated.

Beyond The Screen: Silk As Popular Myth

If cinema gave Silk Smitha her stardom, it was popular imagination that made her a myth. Unlike many heroines who disappeared once the reels stopped rolling, Silk seeped into the idioms of everyday life. In Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh, jokes, catchphrases, and street songs invoked her name to signal desire, mischief, or excess.

To whistle at a Silk number was not simply to respond to a film. It was to participate in a cultural ritual where her image became shorthand for sensuality. Her body was not just cinematic; it became social currency. Her look, saris draped low, bold jewellery, heavy kajal, became a shorthand for sensuality in parodies, stand-up comedy, and local theatre.

The aura of Silk was kept alive through rumour as much as reel. Gossip magazines of the 1980s thrived on stories about her alleged affairs with producers, politicians, and stars. Whether true or fabricated, these stories circulated as part of the Silk legend, feeding into a narrative of a woman who lived dangerously, outside the bounds of “respectable” femininity. She was cast simultaneously as temptress and victim, her life imagined as an endless continuation of her on-screen roles.

The tragedy of her suicide in 1996 only amplified the myth. Much like Marilyn Monroe in Hollywood or Divya Bharti in Hindi cinema, her premature death transformed her from a controversial star into an icon of excess, vulnerability, and unfulfilled desire. The circumstances of her death – alone, allegedly in debt, struggling with the industry that once celebrated her – fed into a narrative of a woman consumed by the very system that created her. In this way, Silk was folded into a longer cultural pattern: the erotic star who burns too brightly, too briefly.

Even after her death, Silk remained a living presence in South Indian cultural memory. Filmmakers mined her image, most famously in Milan Luthria’s “The Dirty Picture” (2011), where Vidya Balan’s performance paid homage to Silk while also dramatising the contradictions of her life. Street posters, memes, and even contemporary item numbers sometimes trace their lineage back to her, reminding audiences of an energy and charisma that never quite vanished.

Importantly, the popular myth of Silk Smitha is not static, it has been reinterpreted across generations. For some, she remains a symbol of unrestrained sexuality, the woman who gave desire a public face in conservative societies. For others, she is remembered with empathy, as a casualty of an exploitative industry and a moralistic society that consumed her body while denying her personhood. This ambivalence, between fantasy and pity, celebration and condemnation, is precisely what makes her myth so enduring.

In the end, Silk Smitha exists not only in her films but in the imagination of those who watched her, gossiped about her, and mourned her. She lives on in the whistle of the front-benchers, the whispers of moral guardians, the nostalgic reruns of 1980s masala films, and the cultural aftershocks of “The Dirty Picture.” Beyond the screen, Silk became both a legend and a cautionary tale, an embodiment of cinema’s ability to turn a woman into spectacle and story, goddess and ghost, a living ghost in India’s cultural unconscious.

Silk In Her Own Voice, Silk In Others’ Memory

Silk Smitha was never the one-dimensional “sex symbol” that popular memory often reduces her to. Directors who worked with her recall a woman of rare clarity and fearlessness. As filmmaker Anil observed, “She had no masks… she was very open-minded and told things right in your face. I doubt if we have heroines as bold as her in our times.” Dennis Joseph, who cast her opposite Mammootty in “Adharvam,” echoed this sentiment, insisting that she was “disciplined and obedient… intelligent, well read and worldly wise,” far from the tabloid caricature that dogged her career.

Silk herself repeatedly voiced ambitions that transcended the glamour tag, confessing in a 1984 Filmfare interview, “Well, actually I wanted to become a character actress like Savithri, Sujatha and Saritha… my ambition remains the same.” Her stardom, however, had its own gravitational pull; as film historian Randor Guy noted, “Films that had lain in cans for years were sold by the simple addition of a Silk Smitha song.” Yet behind the spectacle was also a woman deeply conscious of dignity – Anuradha remembered her halting a shoot until the crew was given drinking water, a reminder of her empathy and collective spirit.

When malicious rumours shadowed her, she responded with disarming candour: “Naturally, there must be several people who are jealous of my success… they’re trying to damage my reputation.” Taken together, these recollections sketch a portrait of a star who was not merely consumed by the industry’s gaze, but who negotiated it with intelligence, humour, and an unshakable awareness of her worth.

The Woman Who Wouldn’t Fit

Silk Smitha’s life and career resist easy categorisation. She was never just a vamp, never only an erotic star, and certainly not a mere tragic figure. Instead, she embodied the contradictions of an industry and a society caught between repression and desire, morality and commerce, patriarchy and women’s self-assertion. By being unapologetically herself on screen, she unsettled the neat boundaries cinema tried to draw between the “virtuous heroine” and the “fallen woman.” She brought to the fore a different kind of female presence – desirous, demanding, and unforgettable.

Unlike heroines who transitioned from glamour to “respectable” mother roles, or dancers like Helen who carved out a distinct yet contained space, Silk never fit the moulds available to women in cinema. She was too sexual to be domesticated, too popular to be ignored, too independent to be controlled, and too vulnerable to be safe.

This refusal or inability to fit into existing categories is what made her both dangerous and magnetic. Silk embodied what sociologist Ashis Nandy calls “the politics of cultural discomfort.” Her very presence reminded cinema-going publics of the desires that polite society sought to repress, while exposing the industry’s own exploitation of caste-marked bodies as repositories of sensuality.

Her legacy endures precisely because of this misfit quality. She was not assimilated into the canon of “respectable” heroines, yet her absence from that canon only sharpened her presence in popular memory. From the 1980s front-benchers who adored her, to the 2011 film “The Dirty Picture” that reintroduced her to a younger generation, Silk’s myth continues to circulate as a story of excess, defiance, and loss.

To remember Silk Smitha today is not only to recall her sultry dances or tragic end. It is to confront the structures of gender, class, caste, and morality that both produced and destroyed her. It is to see in her story a mirror of Indian cinema’s uneasy relationship with female sexuality, and a society’s ambivalent embrace of the women who refuse to be contained.

Silk Smitha was, ultimately, the woman who wouldn’t fit on screen, in the industry, or in the social order. And that is why she remains unforgettable: a star whose shine was not in conformity, but in her refusal to be anything less than herself, no matter the cost.

![[WATCH] Video Essay Explores How Christopher Nolan Manipulates Time](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Christopher-Nolan-768x332.png)