When “The Matrix” was released in 1999, we were introduced to a whole new world of simulation, before artificial intelligence had officially arrived. A machine-controlled world, meticulously elaborated, pushed us to question everything, to break free from self-imposed limits and social conditioning through acts of conscious choice, opening a path toward inner power.

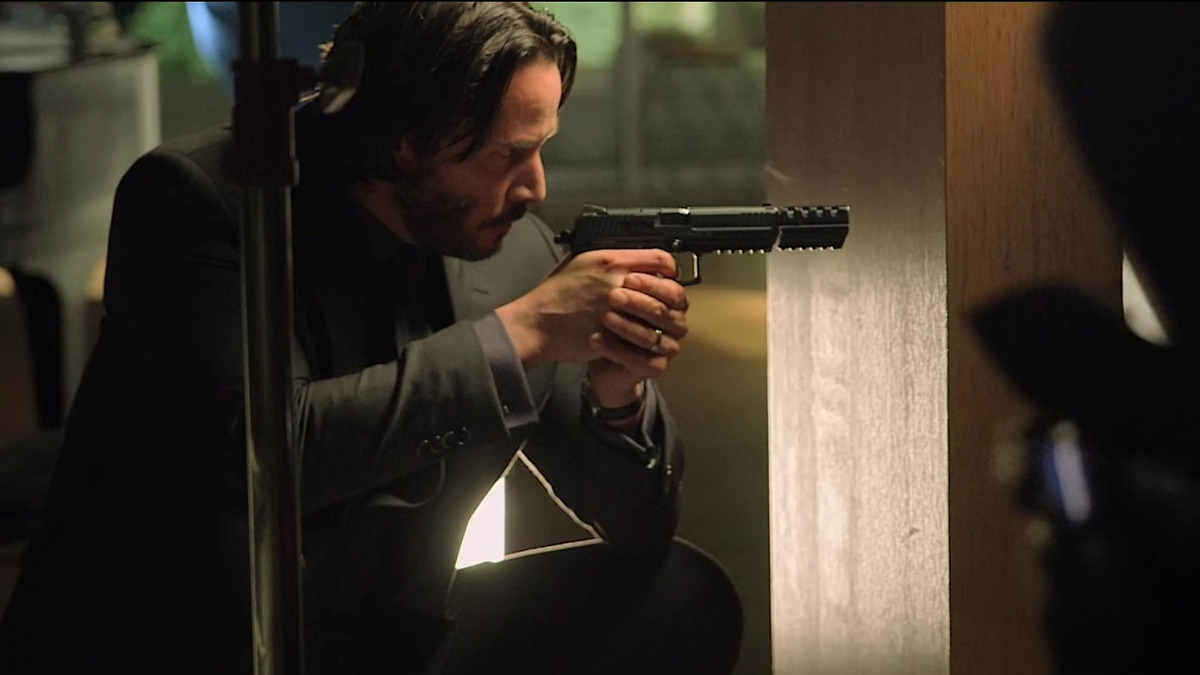

Keanu Reeves is careful in selecting such films where personal belief over illusion, trusting our ingrained systems, and finding inner powers after realizing our true potential becomes the real definition of us. “John Wick” universe expanded on The Matrix’s ideologies, to consider our free will versus determination: how far can we go to endure that pain; to explore the reality, embarking on a profound journey of liberation from mental and physical prisons.

Remember, when the little kid in “The Matrix” said, “There is no spoon”? Neo (played by Keanu Reeves) couldn’t understand until he “believed” that the rules can be bent by changing our own minds and perceptions. It is not the object itself but our changing of reality with our brains. It is a Buddhist philosophy that power comes from consciousness when you know how to manipulate it.

I suppose Chad Stahelski and David Leitch developed “John Wick” based on this very notion. Especially, Chad, because the Wick is Pain documentary narrates all the details of how one of the most impossible franchises came into being with Chad’s unimaginable beliefs of how action should be, and that too, without rules. The story behind the making of all four “John Wick” films and its journey from an independent film to a billion-dollar franchise is directed by Jeffrey Doe. It reveals the details of how the indie film overcame production hurdles and became a rave among the fans. It was not an easy journey, and most of the documentary includes chronicles of how “John Wick” (2014) was made.

Gathering the first production funds of six and a half million dollars appeared to be the most daunting task of making an explosive Wick universe for the times to come. Chad himself was panicked as he was working with THE Keanu Reeves, and “you don’t wanna let him down.” Even the key producer, Basil Iwanyk, disclosed in “Wick is Pain” that he “took money out of his house” to fund the first film. The remaining six million dollars was offered by Eva Longoria, giving her special credits as a producer in the first film.

Why did audiences embrace it from the moment the first trailer dropped, while producers hesitated? Apart from Longoria and Iwanyk, no one was willing to put money behind the project. Chad and much of the crew were scrambling to raise six million dollars by Monday just to get the film into production. So what made “John Wick” feel so singular? The documentary traces the franchise’s unlikely rise, beginning with its scrappy indie origins and the obsessive commitment that powered it forward. It highlights the hyper-stylized action that came to define Wick, even as it acknowledges that similar aesthetics had surfaced in earlier films.

What distinguished Wick was not invention but refinement. By bending the rules of cinematic violence, by treating combat as a closed system with its own logic, the films elevated brutality into ritual. The documentary points out that this approach echoes ideas explored years earlier in “The Matrix,” which had already framed action around belief, perception, and the rejection of limits. Wick didn’t reinvent that language; it distilled it, sharpened it, and delivered it with relentless precision.

The John Wick universe seems to be a fantastical fairy tale kind of story with its own world, its own community of assassins who have a High Table with special coins. There is a clear citation of the fact in the documentary that no plans for a sequel were present until the mega-success of the first feature. The first step in genre defiance that the “John Wick” film made was killing a dog in a Hollywood film, which is usually considered a sin. Chad recounted that on the first screening of the film, half of the people walked out as soon as they saw the dog killed. However, the emotional connection of the rest of the film, transforming into a revenge film, is what worked brilliantly to gain the audience’s love for Wick.

Chad went on to explain that John Wick is loved so much because, for him, no relation is a throwaway, even though he is an assassin. Wick is pain because it shows how people can survive the unbelievable things in the world, and still come out stronger, or even dangerous at times. Chad believed that he could do whatever he wanted because the “John Wick” universe didn’t have any rules. They could change anything, any time, as we know action evolves over generations. He used to be on cloud nine when somebody else said, “Hey, that’s a John Wick thing.” He felt it was something incredible as John Wick created some benchmarks, especially in Gun-Fu.

Also Check: Baba Yaga’s Bullet Ballet: John Wick and the Rebirth of Modern Action Cinema

“John Wick” didn’t invent gun-fu, but it perfected and mainstreamed it. Other films before John Wick also involved stylized action, as some of the other popular ones at that time were trained at Chad’s 87 Eleven stunt coordination company, such as “Atomic Blonde” (2017), “Deadpool 2” (2018), “The Bullet Train” (2022), and “The Hunger Games” (2012 onwards), etc. While others laud the groundwork of gun-fu, “John Wick” graced it with practical, rapid-fire shooting, blending it with Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, Judo, and tactical firearm training. It was the “real” hard work, combined with cinematic styling, that clicked the trick.

The intense hyperreal action epitomized the Hollywood film genre with special Gun-fu sequences. The action is meant to be painful, and the documentary shows clear cuts, bruises, mentions of broken ribs, and swollen knees that brought the film’s allusions to literature, culture, and visual arts to life. Chad loves working like a ninja; nobody knows who’s behind the suit, but the magic is created. He idealized sitting in the theatres, telling everybody, “yeah, that’s me”. The stuntmen continued to emphasize the same idea as they jokingly admitted that they had died many times in Wick films, and it was fun narrating to their friends that it was in a particular scene.

Having the freedom to do something new that no one has ever done in the action genre gave a liberty to align the energies where the spell was locked in. Chad confessed that he was an Etch A Sketch kid, and the idea of top notch action sequence was inspired by it. He didn’t want to hide every action behind numerous cuts and edits. He was fed up with “hiding, hiding, and hiding.” Instead, he thought, “What if we don’t want to do the hiding?” And voila!

In “John Wick 4,” the top-shot action sequence in a Parisian apartment showcases the walls of the building divided, allowing the audience to see all the action unfold simultaneously from an overhead perspective. It was inspired by “The Hong Kong Massacre” video game, featuring dragon-breath shot gun blasts and bullet ballet- a concept that helped crystallize another new John Wick effect. If the rules don’t exist, where would Chad’s imagination stop?

“John Wick” arrived at a moment when Hollywood action cinema felt exhausted, dulled by hyperactive editing and weightless CGI. Earlier films had already begun reshaping the genre’s visual and physical language, from “The Raid: Redemption” (2011) and “Taken” (2008) to “Equilibrium” (2002) and “The Bourne Identity” (2002). Yet Wick cut through the noise by committing fully to impact, clarity, and consequence.

Its action emphasized long, precisely choreographed takes that preserved a sense of physical pain and spatial logic. That discipline extended beyond combat into world-building, with a stylized underworld shaped by neon-soaked, graphic, almost anime-inflected imagery, most pronounced by the time of “John Wick: Chapter 4” (2023). Anchoring all of this was a deceptively simple emotional core, a man’s grief and rage over the death of his dog, which gave the spectacle weight and helped it resonate far beyond genre fans.

The Baba Yaga hitman returned each time with a new vigour, challenging his own limits, even when Chad said, “Don’t do your best, do my best.” The team declared that Chad never accepted ‘no’ for an answer, and that is when something special happens. It comes as no surprise that “John Wick 4” was the one he was most proud of. It was “John Wick 4” where he further defied the genre constraints, reaching a fusion of Japanese and samurai versions. Reeves had to further suffer the pain when he had to train extensively for months to incorporate nunchucks. Chad loved “John Wick 4” for the freedom it claimed beyond the genre’s usual limits, folding anime influences, heightened framing, deliberate composition, and expressive depth of field into the language of action. With Donnie Yen on screen, escalation became inevitable.

Though earlier action films were working on some of the elements, what made “John Wick” distinctive was its scene construction. Chad avoided the shaky camera work and deliberately used smooth long takes, taking time through the scene when a person is walking into a building, staging the scene as wide as possible to show the grandeur of the High Table’s spaces.

The documentary ends with an affirmation that pain makes us suffer, but pain is good. Pain justifies all the hard work since it is a sign that you want the best for yourself, and best, certainly, comes with a cost. Pain helps us grow, pain drives competition, and Chad professed that he has a competition with himself. Competition is what drove him, shaping every sequence of “John Wick” and achieving creative breakthroughs.

Even the ex-director of the first “John Wick” film, David, agreed that he has no competition with Chad as he is what he is. Chad is Wick, Wick is Chad, Wick is pain, and pain does not necessarily come from bad things. It comes from choices. The “John Wick” franchise was about all the choices to defy the genre’s conventions, and that is what broke them free. Wick is a movie magic- the result of immense effort, made possible by people pushing themselves to do their best while working with the best. Reeves ends by saying, “Wick is pain, wick is surviving, wick is grieving, wick is friendship, wick is love…all big ideas in this ‘action’ movie…and wick is funny.”

![Melancholia [2011]: Alien on Earth](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/melancholia-04-768x432.jpg)