“If you ever feel like crying, come to my house. We’ll have a good cry together”, says the perseverant teacher, played by the beautiful and strong-willed Hideko Takamine in Keisuke Kinoshita’s pacifist post-war Japanese classic, Twenty-Four Eyes (Nijushi no hitomi, 1954). The line pretty much sums up our emotional reaction to the narrative in which writer/director Kinoshita skillfully expresses the inhumanity of war and jingoism. Twenty-Four Eyes is one of the best examples of melodrama done well where it transplants us to share the affective space of grief and compassion as felt by the characters. It might be a conventional story of wartime oppression, punctuated with copious tears. However, Kinoshita’s style which contrasted moving close-ups of teary-eyed children with placid, lengthy panoramas, hits upon robust emotional truth without getting lost in the sentimentality.

Twenty-Four Eyes is one of the most popular postwar Japanese films. Made three years after the end of American occupation, it was considered as a national treasure and became the ‘most awarded film’ in Japanese movie history. It’s important to note that Twenty-Four Eyes released in the same year other landmark Japanese films released: Seven Samurai, Sansho the Bailiff, Gojira, and Sound of the Mountain. Moreover, Kinoshita’s feature was more of a pacifist drama that relies heavily on nostalgia than being a strident anti-war picture like Kobayashi’s Human Condition Trilogy (1959-61) or Kon Ichikawa’s Fires on the Plain (1959). Critic David Blakeslee explains that such intense anti-war picture would have been impossible without films like Twenty-Four Eyes which ‘cleared path for them in the cultural consciousness’ [1].

Based on the 1952 novel by Sakae Tsuboi and adapted to screen by Kinoshita himself, Twenty-Four Eyes isn’t attempting to convey the immensity of the hardships during wartime Japan, but touches upon the collective trauma of Japanese during those years of militarism and repression. Since we the viewers too share this space of suffering, the tears brings catharsis of sorts. Furthermore, Kinoshita’s humanist gaze gently underlines the so-called Japaneseness. As Audie Bock in her Criterion essay describes, “It lives on, however, not as a melodramatic tearjerker but as a meticulously detailed portrait of what are perceived as the best qualities in the Japanese character: humility, perseverance, honesty, love of children, love of nature, and love of peace” [2].

Related to Twenty-Four Eyes: The Only Son [1936] Review – The Characteristic Ozu Style at its Nascent Stage

Twenty-Four Eyes is set in the years between 1928 and 1946 on the Shodoshima island in the Inland Sea of Japan. It follows the life and experiences of Hisako Oishi, a freshly-qualified elementary school teacher who develops a special relationship with her first twelve 1st grade school pupils. Miss Oishi is first seen entering the poor seaside village in a bicycle and sporting western-style clothes. This generally makes the conservative adults of the village to mistrust her. The children see their ‘modern teacher’ with a mixture of fascination and doubt. Oishi means ‘Big Stone’, but her short stature pushes the kids to nickname her, ‘Miss Pebble’. This nickname sounds more poetic and evocative later in the narrative when Oishi endures the torrential currents of social oppression, war and famine.

In the eyes of the twelve 1st grade kids (twenty-four eyes), Oishi sees a future full of rich possibilities. Kinoshita’s poignant close-ups of the twelve kids early in the narrative when Oishi notes down their nick-names in the attendance register instantly creates an emotional bond. The memory of this scene keeps flashing in our mind when Kinoshita tracks the growth of twelve innocent children, each consumed by their own personal tragedies. The harsh economic conditions imposed first by the financial depression and then the war are largely viewed through the sufferings of Oishi and her pupils. The wider world events are notified to the viewers by on-screen texts that informs from 1931 Manchuria incident to the post-war penury. Children folk songs plays a significant role in Kinoshita’s narrative and the director’s brother & composer Chuji’s choice of including themes such as ‘Auld Lang Syne’, ‘Annie Laurie’ is intriguing.

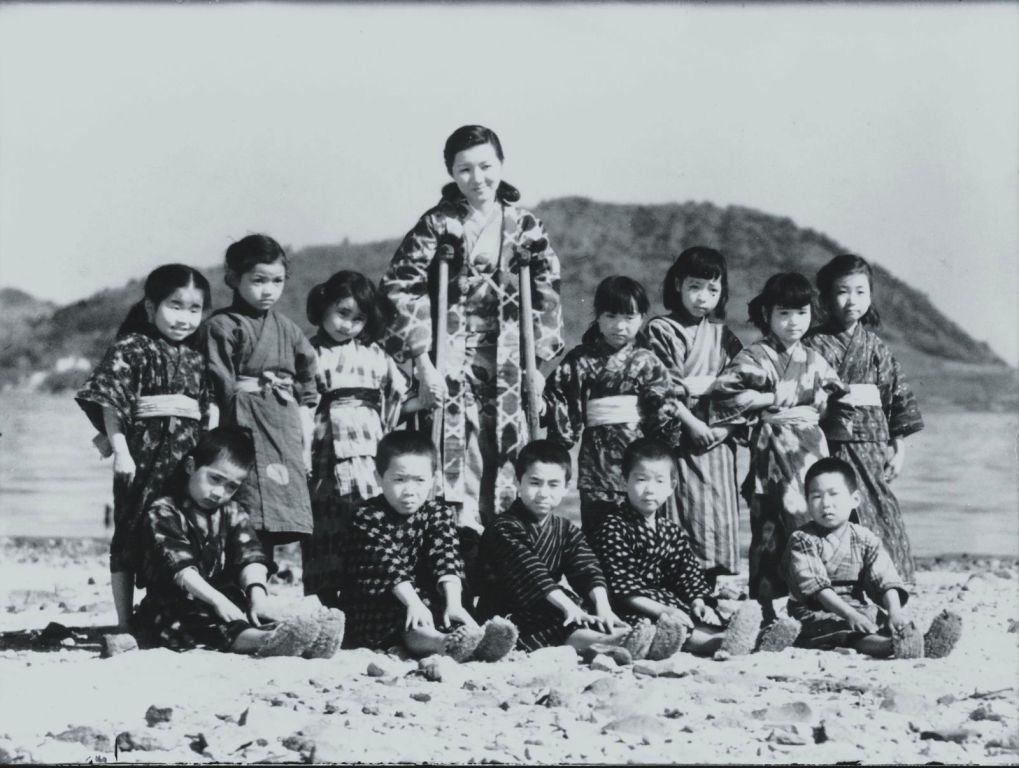

In 1928, Oishi sings with her class kids near the seashore and play games. However, the students’ gentle prank goes wrong when Oishi injures her leg. Yearning for Miss Pebble’s comforting presence and stricken by guilt, the twelve children decide to pay her a visit. It leads to the narrative’s decisive moment where Oishi sensei and her class pose for a group photo which plays one of the key roles in delivering the plot’s epic sweep. Sadly, Oishi’s inaugural year ends with the accident and she moves to teach at consolidated school for the sixth-grade. Amidst the tearful farewell, she promises to catch up with them in five years.

Oishi’s reconnects with the twelve once they reach sixth-grade. But owing to the financial climate of the era, some move away and some start working for their families. The ones who graduate high school are caught up in the frenzy of war and march off to the battlefield. At school, in her own limited ways, Oishi pushes back against the school administration when they clamp down on ‘red literature’. She also openly expresses her aversion towards war to her students. Oishi is however married to navy man who gets drafted and gets killed in the war. She has three children and feels relieved once the Emperor announces Japan’s surrender. Her eldest, Dakichi asks, “Aren’t you going to cry because we lost, mother?” To which she pensively replies, “I cried for the dead. I cried and cried.”

After the end of war, the prematurely aged Oishi returns back to the teaching at the same elementary village school. She weeps at the sight of her past students’ children, their innocent faces once again sparkles with great possibilities. Nevertheless, Oishi’s affectionate tears, shed out of sorrow as well as joy, earns her a new nick-name among the 1st graders – Miss Crybaby or Crybaby sensei. The film ends with a deeply emotional reunion which brings together Oishi and her surviving members of her first class. They look at the class photo taken so many years earlier. Though we have spent just over 150 minutes with these characters, we can also feel the passage of time and the weight of their suffering. The sunny afternoon ends with a song; an offering of hope amidst the horror of loss and trauma.

Also, Read: A Fugitive from the Past [1965] Review – Probing the Postwar Devastation of Japan through Thriller Framework

Twenty-Four Eyes reminded me of William Wyler’s multiple Oscar-winning classic, The Best Years of Our Lives (1946). Just like Wyler’s earnest portrait of American psyche affected by the war, Kinoshita attempts to come to terms with their traumatic past in a very simple yet lovingly intimate way. Of course, there has been lots of debate over Kinoshita’s treatment. Though Kinoshita’s aesthetic sensibilities brings a natural flow to the narrative – the moving close-ups and long shots of idyllic atmosphere remain in perfect harmony – critics have noted the film’s heavy emphasis on the suffering of the Japanese while totally refraining from acknowledging the damage inflicted by Japanese imperialism.

That may be true, but the benefit of hindsight works in favor of Kinoshita since there’s something resonating and timeless about Oishi’s tears and hopes. Her preference for life over death extends beyond the confines of Japanese wartime history, transmitting a quietly powerful message for the contemporary times where militarism and regressive ideologies are once again on the rise. Eventually, it is the versatile Hideko Takamine’s restrained performance that adds realistic touches to Oishi’s suffering and perseverance.

Overall, Twenty-Four Eyes (156 minutes) transcends the limitations of a sentimental tearjerker with its finely honed imagery – emphasizing on the transience of life – and phenomenal performances.

Notes:

- David Blakeslee, Criterion Reflections, April 24, 2010.

- Audie Bock, Twenty-Four Eyes: Growing Pains, Criterion Essay, August 18, 2008.

![The Realm [2018] Review – A Brilliantly Paced Political Thriller](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/The-Realm-2018-768x512.jpg)