Japanese cinema is one of the oldest and most prominent film industries engaged in motion picture production. Horror cinema always occupies a special place among the industry’s various genres, which includes the globe-trotting popularity of anime. While Japanese horror cinema offerings differ from Western horror in terms of aesthetics and themes, the rise of J-horror in the late 1990s has brought much intellectual inquiry into its unique cinematic horror elements. From the groundbreaking post-war monster feature, “Gojira” (1954), to the wildly successful “Ringu” (1998), Japanese horror cinema is often grounded in profound cultural context.

Apart from showcasing harrowing tales of enraged ghosts, Japanese horror also focuses on personal and collective fears, whether in feudal or modern Japan. Onryo—the vengeful spirit—in “Ringu” and “The Grudge” does terrify us. However, some of the best Japanese horror films show how the human mind is truly the scariest thing of all. The descent into madness and losing one’s sense of self is a recurring element in many of these Japanese horror movies, i.e., from Kinugasa’s trippy silent film to Tsukamoto’s twisted psychological horrors.

The list aims to recognize the wide range of Japanese horror films. But there will always be the question of what constitutes horror cinema: whether it is defined by genre parameters or something bestowed upon content that disturbs, unnerves, and repulses a viewer. As such, there will be questions about including and omitting certain titles. Nevertheless, this list is not a definite one since my perception of Japanese horror cinema will go through changes with rewatches and after discovering more hidden gems. Now, let’s look at the twenty best Japanese horror films:

1. A Page of Madness (1926)

European cinema in the 1920s broke away from narrative conventions to experiment with the cinematic medium, which was still in its infancy. German Expressionist films, French Impressionist movies, and Soviet Montage Theory started treating cinema as a distinct art form far removed from the immediate commercial concerns. In Japan, jidaigeki swashbucklers and Kabuki adaptations comprised most of the country’s silent cinema output. But Teinosuke Kinugasa (who once played female roles in Kabuki theater) made an unsettling self-financed silent film inspired by the German Expressionist film, “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari” (1920).

Based on a short story by Nobel Prize-winning author Yasunari Kawabata, “A Page of Madness” (“Kurutta Ippeiji”) is set in a mental asylum where a retired sailor takes up the job of a janitor. He is there to look after his wife, whom he has abandoned and who is locked away because of a traumatic incident. Nevertheless, this plot description wouldn’t wholly convey the dark and hallucinatory viewing experience. Restored in 1971 (long believed to be lost, it was found in the director’s garden shed), “A Page of Sadness” does not feature any intertitles. This absence only makes the story more oblique and expands the scope for interpretations. Even though we sometimes don’t know what exactly is going on in the 70-minute film, this is one terrifying vision of an individual’s descent into madness.

Related to Best Japanese Horror Films: 15 Essential Japanese Silent Films

2. Gojira (1954)

Ishiro Honda’s path-breaking kaiju movie, “Gojira,” might today be considered as an action-adventure flick. In fact, many of the Godzilla iterations in Japan and Hollywood didn’t lean into horror elements. But in post-war Japan, the prehistoric monster and its rampage in Tokyo Bay present the Japanese people’s palpable fears of widespread destruction. Godzilla itself was a potent metaphor for the nuclear bomb. Even though contemporary viewers are far removed from understanding the tensions of that era, Honda’s “Gojira” still contains the power to terrify us. One particular standout moment is the monster’s attack on Tokyo.

The fire-breathing Godzilla’s unstoppable march through the Tokyo streets taps into the collective trauma of war. Even the keloid scars on Godzilla resemble the survivors of the atomic bomb. While there is a critique that “Gojira” uses the monster to present Japan as an innocent victim (downplaying the nation’s war atrocities), Honda’s focus is primarily on the civilians and evokes the horrors of war. The invention of the H-bomb is likened to the emergence of a mutated beast. Gojira is humanity’s creation, and the terror lies in the fact that it has come back for vengeance.

3. Kwaidan (1964)

Masaki Kobayashi’s three-hour quartet of ghost stories is based on Lafcadio Hearn’s supernatural Japanese folktales. Mr. Hearn was an Irish-Greek author who fell in love with Japan when he was sent there as a correspondent. The writer is often credited with introducing Japan’s culture and literature to the West. Renowned screenwriter Yoko Mizuki (who frequently collaborated with Mikio Naruse in the 1950s) adapted the stories for screen. While Kobayashi was previously known for realistic dramas like “The Human Condition” Trilogy and “Harakiri,” with “Kwaidan,” he opted for ceaselessly imaginative expressionistic visuals. Drawing heavily from the Noh plays, these haunting tales are shot on colorfully surreal studio sets with meticulously prepared backdrops.

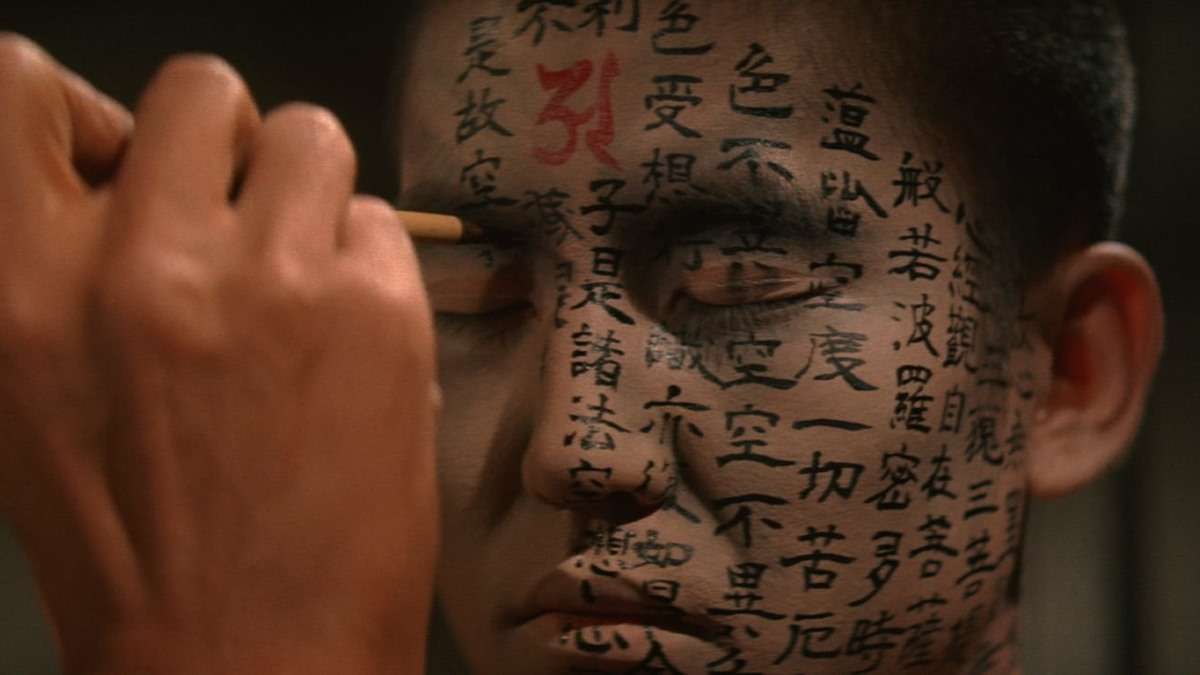

Set in feudal Japan, the four tales in “Kwaidan” are titled “The Black Hair,” “Women of the Snow,” “Hoichi, the Earless,” and “In a Cup of Tea.” Kobayashi’s engrossing mise-en-scene casts each of the four tales a distinct otherworldly spell. While the outcomes of these ghost stories are somewhat predictable, the joy is in savoring Kobayashi’s rich visual flavor. Apart from Toda Shegemasu’s art direction and Miyajima Yoshio’s cinematography, “Kwaidan” is blessed with Toru Takemitisu’s avant-garde score. The inventive music adds a lot to the film’s unnerving quality. Though “Kwaidan” is far removed from the realism of his films, Kobayashi delivers the familiar cautionary message about repeating the mistakes of history through these demons and undead samurai.

Related to Best Japanese Horror Films: 30 Best Tatsuya Nakadai Movie Performances

4. Onibaba (1964)

In 1960, Kaneto Shindo made the sparse Sisyphean drama “The Naked Island,” which chronicles the story of a family’s arduous survival on an arid island. Shindo’s “Onibaba” also follows two women—old and young—fighting for their survival in 14th-century Feudal Japan engulfed in civil war. But “Onibaba” is far removed from the documentary-realism of “The Naked Island,” as it unfolds like a fable with eerie, supernatural-tinged sequences in the final act. “Onibaba” doesn’t strictly fit into the West’s concept of the horror genre (although “The Exorcist” director Friedkin addresses it as “the scariest film I ever saw”). However, Shindo’s harrowing study of the corruptible and violent nature of humans maintains a chilling atmosphere throughout.

Hikaru Hayashi’s jolting score also perfectly accompanies this nightmarish vision of humanity. Set in the land of tall susuki grasses, “Onibaba” opens with a woman and her daughter-in-law murdering wounded soldiers wandering into their field. They dump the bodies in a deep hole and sell the armor and sword to the black marketeer for food. The woman hopes their desperate attempts to survive will change once her son returns from the war. But to her dismay, only her uncouth neighbor, Hachi, returns home, bearing the news of the son’s death. His sexual desire for the woman’s daughter-in-law threatens the interdependent relationship between the two women.

Gorgeously shot in black-and-white by Kiyomi Kuroda, Shindo unflinchingly portrays the horrors and anxieties of ordinary humans that are real and compelling enough. It’s astounding how Shindo matter-of-factly presents the lust, greed, and violence that drive these three central characters. We can feel the primal, gnawing sense of hunger lying beneath these human masks, which is often terrifying to behold.

5. Kuroneko (1968)

Kaneto Shindo’s “Kuroneko” (Black Cat) shares some of its thematic elements with Shindo’s internationally acclaimed arthouse horror, “Onibaba.” Moreover, like “Onibaba” and many of the ghost tales of the era, “Kuroneko” isn’t a scary film. It has a few genuinely unnerving moments, but it is primarily an aesthetically pleasing feature that critiques the samurai system. “Kuroneko” opens with a disturbing, wordless sequence as a group of wandering samurai approach a hut situated amidst a bamboo grove. The hungry samurai come across a woman and her daughter-in-law. Apart from ravenously consuming their food, the samurai sexually assault the women. Eventually, they kill them and burn down the hut.

A black cat licks the women’s charred bodies, transforming them into cat demons seeking revenge on the samurai. From then on, the spirit of the daughter-in-law lures any lone, unsuspecting samurai to their household and later attacks the samurai in an animalistic manner. The mother does a ceremonial dance of death. When the news of multiple samurai deaths reaches the local lord, a warrior is sought out to kill the ‘monsters.’ But the warrior’s identity doesn’t make it easier for the ghosts to kill him like the other samurai. Similar to “Onibaba,” “Kuroneko” has a straightforward plot that largely depends upon its rich and stunning atmosphere.

The latter half of “Kuroneko” has a few melodramatic portions. Nevertheless, the creepy climax confrontation was brilliantly staged, and the wire works and other filmmaking tricks were neatly embedded into the haunting final moments.

6. Blind Beast (1969)

Yasuzo Masamura has worked in diverse genres and is one of the key influencers of the Japanese New Wave. “Blind Beast,” based on an Edogawa Ranpo story, is one of Masamura’s most outrageous feature films. The narrative walks the tightrope between an arthouse and a sexploitation flick. Michio (Eiji Funakoshi) is an unhinged visually impaired sculptor who, with the help of his mother (Noriko Sengoku), kidnaps Aki (Mako Midori), an attractive model. The narrative largely takes place in Michio’s secluded warehouse, filled with biomorphic female anatomy sculptures.

Aki’s attempts to escape by seducing Michio fail. Subsequently, what unfolds is a twisted and perverted relationship that’s unimaginably dark and bizarre. Though the kind of sadomasochistic relationship portrayed here is prevalent in exploitative flicks before and after “Blind Beast,” Masamura’s endlessly fascinating visual style and great performances transcend such narratives’ conventional dynamics and action. The intense and shocking final scene precedes the violent climax of Oshima’s “In the Realm of Senses.” Yet Masamura’s hyperrealistic portrayal of dismemberment disturbs us without explicitly showcasing violence. Like many of the movie adaptations of Ranpo’s stories, “Blind Beast” is both dazzling and repulsive.

7. Demons (1971)

Toshio Matsumoto’s “Demons” isn’t about malevolent otherworldly entities but the darkest creatures of our human society. Based on a Kabuki theatre play (first staged in 1825), “Demons” – adapted by Matsumoto himself – isn’t an easily categorizable movie. There are quite a few dark samurai films, particularly Kihachi Okamoto’s “Samurai Assassin” (1965) and “Sword of Doom” (1966). The latter, featuring Tatsuya Nakadai as the skillful yet nihilistic samurai, gave us one of the most transfixing portrayals of evil onscreen. But the seemingly honorable Ronin Gengobei’s (Katsuo Nakamura) descent into madness is purely horrific.

While the explosion of violence in the final third of samurai flicks is nothing new, the bloodshed in “Demons” breaks a few cinematic taboos. Interestingly, a film titled “Demon” (1978) by Yoshitaro Nomura also directs violence toward the most vulnerable. However, Nomura’s film is a grounded drama that’s relatively nuanced when presenting the unsettling moment. With all its exaggerated emotional performances, Matsumoto’s “Demons” is stylized like a psychological horror that the butcheries are hard to shake off.

The narrative tells a simple tale of an impoverished Ronin who is desperate to restore his honor and rejoin the clan with 100 Ryo. But Gengobei is swindled by Koman, a geisha, and her partner, Sangoro. Subsequently, Gengobei embarks on an all-consuming quest for vengeance that turns him into a demon of sorts. Shot in gorgeous black-and-white, the characters’ faces are often partially obscured, signifying the darkness that’s awaiting to engulf them.

8. Hausu (1977)

Nobuhiko Obayashi’s “Hausu” has a haunted house at its center and a supernatural, people-eating villain. But this doesn’t have anything close to a traditional horror narrative. The words ‘psychedelic’ and ‘bizarre’ would be used repeatedly to describe “Hausu.” Yet even those words feel limiting when describing the delirium Obayashi subjects us to. The film revolves around a group of effervescent high school girls vacationing in the countryside at one of the girl’s auntie’s house. Each of the seven girls is addressed by their English nicknames, which somewhat reflect a single defining character trait: Gorgeous, Fantasy, Kung Fu, Professor, Melody, Sweet, and Mac. Things start going bonkers as soon as they arrive at the lonely auntie’s isolated mansion.

Although Obayashi’s “Hausu” has a deceptively straightforward plot, his execution is anything but that. Weird framing, a profusion of practical effects, matte painting, stop-motion animation, and rear projection are among his wild displays of technique, which evoke equal parts exhilaration and bafflement. There are anticipatory moments of terror, but there’s also plenty of tongue-in-cheek humor. Interestingly, Obayashi’s stylized madness is more memorable than most conventional horror movie experiences. “Hausu” can be read as a smug girl’s projection of her anxieties regarding her father’s new wife. On a deeper level, it can be perceived as a tale of youthful ignorance that utterly disregards the painful, traumatic past. But irrespective of the subtext, “Hausu” is a dizzying and eye-poping visual spectacle.

Related to Best Japanese Horror Films: 10 Films To Watch When You’re Stoned

9. Tetsuo: The Iron Man (1989)

Don’t mistake the “Iron Man” in the title as a family-friendly anime version of the Marvel Superhero. This is Shin’ya Tsukamoto’s twisted parable about the relationship between an individual and technology. Exciting, disturbing art goes beyond the formal constraints imposed by societal conventions. Tetsuo: The Iron Man’s unrelenting imagery and hyperactive imagination make it one of the best among the outsider cinema. Like Lynch’s “Eraserhead” and Cronenberg’s “Videodrome,” Tsukamoto’s cult film is a surreal shocker. The filmmaker himself plays the unnamed metal fetishist. In a junkyard, he cuts a hole in his leg and drives a pipe into it.

The ensuing combination of pain and ecstasy takes him to the streets, where the man is hit by the car of a salaryman and his girlfriend. The couple dumps the fetishist’s body, but the accident sets off a chain of uncanny events. The salaryman begins metamorphosing into a human-metal hybrid. Tsukamoto’s hyper-energized visuals and avant-garde storytelling will offend and disgust many viewers. The 67-minute film also gets increasingly abstract and chucks narrative purpose for unbelievable grotesque imagery. Nevertheless, “Tetsuo” is an outlandish dystopian horror, where technology and mechanized stuff infect us like disease, changing us in the ugliest ways possible. The sequel, “Tetsuo II: Body Hammer” (1992), has a more polished narrative and a larger budget, although it doesn’t have the frenzy of the original.

10. Angel Dust (1994)

Gakuryu Ishii (aka Sogo Ishii) is known for pioneering the cyberpunk movement in Japan with films like “Crazy Thunder Road” (1980) and “Burst City” (1982). The filmmaker reinvented himself with the stylistic and dream-like narrative of “Angel Dust.” He followed it with equally wonderful films like “August in the Water,” and “Labyrinth of Dreams.” “Angel Dust” opens like a serial killer thriller as a killer targets young women in subway cars during rush hour, injecting them with a drug that instantly kills them. Dr. Setsuko Suma, a psychological expert, aids the detectives in the case.

The killer’s first victim was a member of a cult, who was kidnapped by her parents and sent to a reverse-brainwash program run by the infamous Dr. Rei Aku, Dr. Suma’s former colleague and lover. What unfolds is puzzling mind games and a descent into madness. In many ways, “Angel Dust” is a fascinating precursor to the much superior “Cure.” Both films deftly incorporate psychological horror elements into the thriller storyline. Moreover, like most J-horror films, “Angel Dust” uses grainy camera footage to create a chilling effect.

Some of the film’s events and storyline might have come across as eerily foreboding, as six months after its release, a religious cult attacked the Tokyo subway with Sarin nerve gas. “Angel Dust” is deliberately cryptic, which can be mistaken for incoherence. But the moody, nightmarish journey of Dr. Suma in the latter half is where the horror elements play a perfect role.

11. Cure (1997)

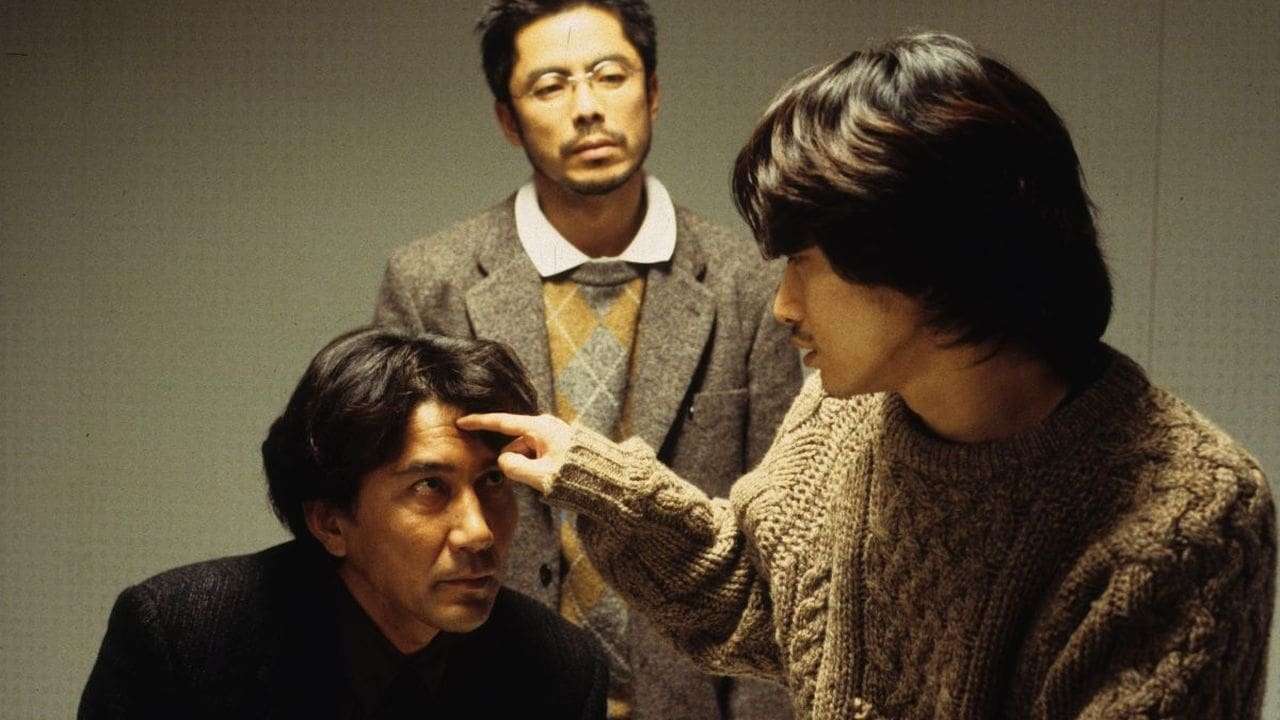

Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s “Cure” has the makings of a police procedural. A series of murders happen in Tokyo, committed by people from different walks of life. But all the perpetrators are compelled to carve an ‘X’ on the victim’s body. Moreover, the perpetrators claim to have no memory of committing a crime. The only connection between the killers is that they have come across Mamiya (Masato Hagiwara), a young and possibly amnesiac drifter. Detective Takabe (Koji Yakusho) investigates the killings and guesses the drifter uses hypnosis to pull off these killings. But if you are looking for neatly packaged answers, “Cure” doesn’t provide any. It’s a sinister and profoundly unsettling movie about the banality of evil.

The visual elements in “Cure” play a pivotal role in creating a sense of unease and dread. From the masterful use of negative spaces to disorienting us with the askew angles, Kurosawa’s framing and composition create several skin-crawling moments. The vaguely detached, observational feel while capturing the horrific moments often catches us off-guard. The police booth and public toilet killings are shown in a matter-of-fact manner that the violence is nauseating to witness. “Cure” leaves us with more questions about the human nature. It examines the idea that evil is so mundane that its corrosive nature can effortlessly corrupt even the most determined individuals.

12. Ringu (1998)

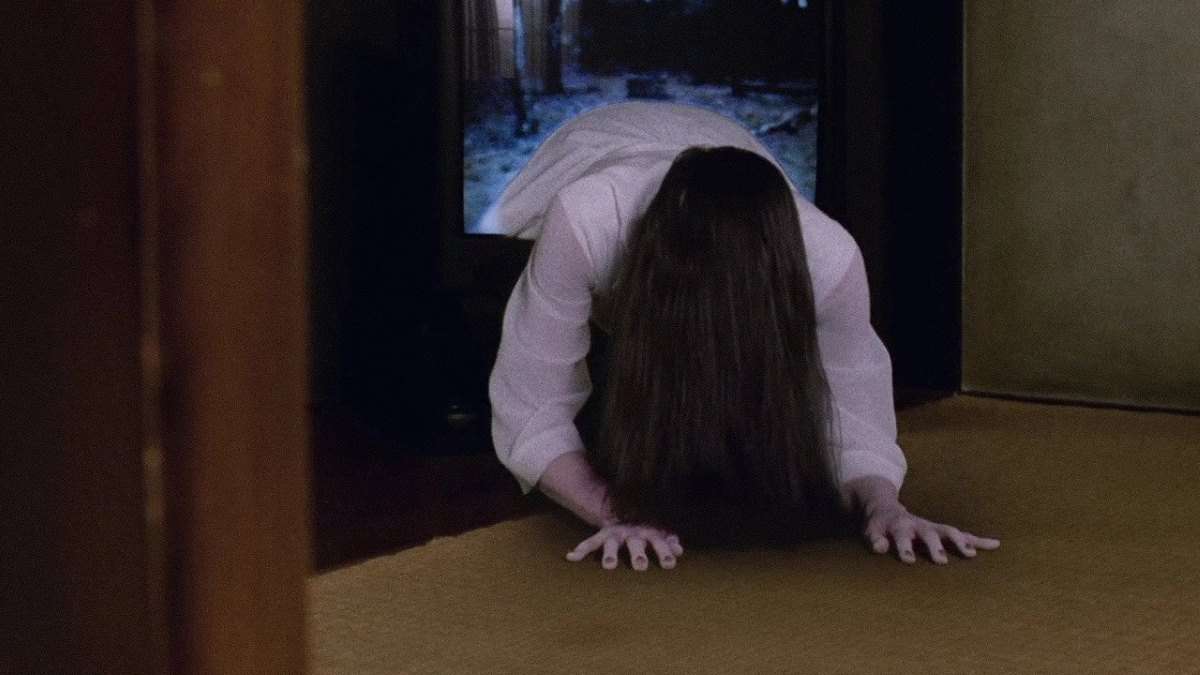

Hideo Nakata’s 1998 adaptation of Koji Suzuki’s 1991 novel, “Ring,” brought international recognition to the Japanese horror genre. Soon, British distribution label Tartan Video coined the term J-horror to distribute the content into the UK market. Then, in the West, J-horror was used to describe the Japanese horror movies of that era. Using a unique style of psychological horror to address contemporary social issues, J-horror expanded the limits of the genre. Though Nakata’s “Ringu” wasn’t the first adaptation of Suzuki’s novel (in 1995, Chisui Takigawa made a TV movie titled “Ring: Kanzenban”), the filmmaker’s hypnotic aesthetics taps into our subliminal fears.

In fact, most Japanese horror released between the late 1990s and early 2000s eschewed in-your-face horror and made us quietly fall under its spell. Perhaps “Ringu” is the most emblematic movie of this visual style. Even those who have never seen “Ringu” might have heard its plot about a cursed videotape that evokes the vengeful spirit, Sadako. “Ringu” transplants the age-old traditional beliefs in Onryo (vengeful spirit) to explore the modern fears about technology. Nakata’s film also explores the themes of single motherhood and ostracization. “Ringu” has had many remakes and sequels. Yet nothing comes close to the profoundly terrifying visual of pale-skinned and long-haired Sadako emerging from the TV.

13. Audition (2000)

The prolific and controversial filmmaker Takashi Miike is known for examining extreme and taboo subjects. In fact, Japanese horror cinema has produced many such boundary-pushing filmmakers, particularly from the 1960s. The fascinating thing about Miike is that he can do nuanced storytelling and gleefully make the most outlandish and gory flicks. Miike’s adaptation of Ryu Murakami’s 1997 novel, “Audition,” looks relatively tame compared to the extreme graphic imagery of “Ichi the Killer.” Yet, Audition’s portrayal of the recognizable male fears and insecurities withholds complexities that resonate beyond the Japanese cultural context.

“Audition” depicts a horrible world, one that’s filled with casual misogyny, alienation, chronic loneliness, and male entitlement. It revolves around Aoyama, a middle-aged widower who sets up a phony audition process to find a new wife. During the audition, Aoyama is attracted to Asami Yamazaki (Eihi Shiina). He is particularly excited about her past and thinks she fits his ideal perception of a wife. But every frame oozes unease as the narrative gradually unearths darker aspects of Asami’s psyche. By the time Asami turns up with a piano wire, it’s too late for the self-pitying Aoyama to come to terms with his arrogance.

There have been many chilling images in horror cinema, and Asami calmly chanting “Kiri Kiri Kiri” while committing an unimaginably violent act is definitely one of the most unforgettable imagery.

Related to Best Japanese Horror Films: 50 Best Japanese Movies of the 21st Century

14. Pulse (Kairo, 2001)

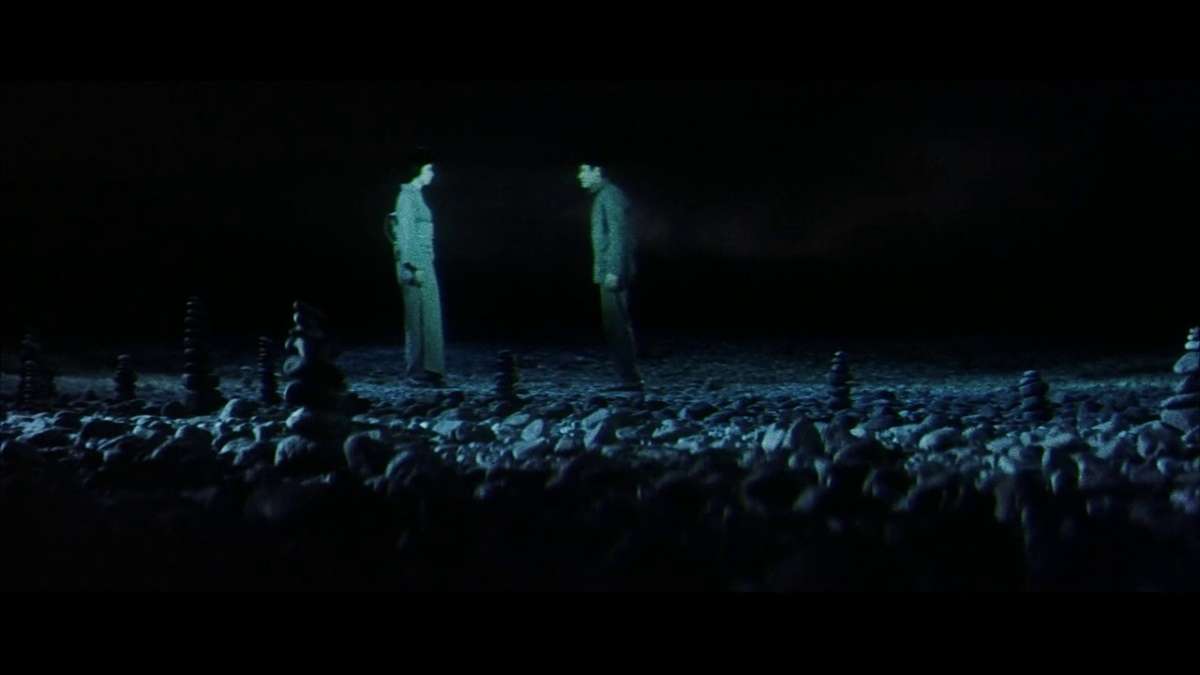

Unlike the obscure and terrifyingly nihilistic horror of “Cure,” Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s “Pulse” focuses on the more familiar fears of technology. Like “Ringu,” “Pulse” also deals with the palpable issues of loneliness and emotional disconnect. Yet, Kurosawa’s uncanny aesthetics and unconventional methods of escalating tension are decidedly singular. The advent of the internet provoked anxieties about the blurred boundaries between the real and the digital. While the internet opened up a larger world to its users, the isolation remained pervasive. Kurosawa’s “Pulse” imagines the eternally alone ghosts invading the human world through the internet.

The film follows two disparate and lonely characters facing an outlandish apocalypse caused by the internet. “Pulse” eerily gets a lot of things right about the dark side of the virtual world. In fact, alongside “Perfect Blue” and the cyberpunk limited series “Serial Experiments Lain,” “Pulse” remains a prescient tale about online horrors. Apart from the thematic concerns, “Pulse” continues to terrify us due to its unnerving atmosphere.

Kurosawa’s brilliant use of shadows and static shots heightens the tension, forcing the viewers to confront the horror head-on. Moreover, the film’s sound design and discordant score play a pivotal role in maintaining the suspense. The 2006 American remake was clearly one of the worst remakes of Asian or Japanese horror films.

15. Dark Water (2002)

While Hideo Nakata has made movies in various genres, he is primarily categorized as a horror filmmaker due to his two extraordinary J-horrors: “Ringu” and “Dark Water.” Ring novelist Koji Suzuki’s short story is the basis of “Dark Water,” which is more character-driven than “Ringu.” Long before the haunting, the film’s central character, Yoshimi, is already on the edge as she and her six-year-old daughter Ikuko move to a flat in the damp, gloomy apartment building. Yoshimi is going through the divorce proceedings and tries to find a job to support the daughter. Her abusive husband, however, tries to deem Yoshimi an unfit mother and win the custody battle. Amidst this tense atmosphere, Yoshimi and Ikuko are haunted by the ghost of a little girl.

Child neglect and abandonment are some of the persistent issues in Japan, which are often portrayed in films belonging to the drama genre. “Dark Water” approaches similar issues through a dark parable. The children in the movie are frequently seen framed in doorways, isolated, and looking at the heavy rain as if they are cut off from the outside world. Yoshimi herself is portrayed as a neglected child, and now, as a single mother, she fears whether Ikuko will also go through fears of abandonment and feelings of isolation. The ghost child Mitsuko’s past and fate add to the tragic dimensions of the narrative.

Similar to “Ringu,” in “Dark Water,” too, Nakata implies terror by suggestion. He acquaints us with the central character’s anxieties and fears, and the supernatural occurrences become an extension or exaggeration of that. “Dark Water” is simply worth watching for the subtlety with which Nakata designs the psychological scares.

16. Ju-On: The Grudge (2002)

Takashi Shimizu’s “Ju-On: The Grudge” is the first theatrically released “Ju-On” movie. Its predecessors – “Ju-On: The Curse” & “Ju-On: The Curse 2” – were direct-to-video films also written and directed by Shimizu. “The Curse” touches on the origins of the onryo Kayako, who is murdered by her husband. The murders of Kayako and her son Toshio revive them as vengeful ghosts whose grudge consumes anyone who enters their household. At the same time, even if you haven’t watched “The Curse,” you wouldn’t miss a lot of details that impact your viewing experience of “The Grudge.”

The “Ju-On” movies largely follow a similar structure: presented in a non-linear narrative, different characters endanger themselves by coming into contact with the malevolent spirit at the house. The episodic narrative keeps us off balance and presents unique haunting scenarios and chilling scares. At times, Shimizu throws in David Lynch-esque moments to disorient us. Yet, there’s not much in terms of character development or emotional investment. Still, the original “The Grudge” withholds quite a few unsettling moments. Each time Kayako claims her victims, shivers run down your spine. The blanket scene, in particular, gave me horrible nightmares. Similar to “Ringu” and “Pulse,” the use of ambient sound elevates the spooky atmosphere in “The Grudge.”

Related to Best Japanese Horror Films: 15 Best Netflix Original Horror Movies

17. Strange Circus (2005)

Sion Sono’s “Strange Circus” is deliberately designed to disorient viewers. Its hallucinogenic narrative makes it challenging to understand which aspects are dreams, memories, the experiences of a character in a novel, and reality. But “Strange Circus” primarily disturbs us because the first section of the film is about a man who sexually and mentally abuses his wife, Sayuri, and his 12-year-old daughter, Mitsuko. The girl narrates her traumatic experiences, and the visuals avoid being exploitative. Nevertheless, Sono evokes an uneasy feeling as Mitsuko’s mental agony twists her reality. We see a recurring image of Mitsuko walking through a blood-smeared hallway.

“Strange Circus” enters into Lynchian territory as the tale of Mitsuko is shown to be a part of a novel in progress by the physically disabled reclusive author Taeko. But there’s a lingering question of whether the novel is autobiographical and if Taeko is a pseudonym of the now grownup Mitsuko. However, there are no straightforward explanations for this morbid tale of sexual abuse, trauma, and jealousy. Sono doesn’t rely on shock value despite dealing with an unsettling topic. The film masterfully keeps us perplexed through the perception of its psychologically unbalanced characters.

In April 2022, in Shuken Josei magazine, Sion Sono was accused by two women of sexual assault. The filmmaker denied the allegations, and by February 2024, the magazine had deleted the articles that initially made the allegations (in the defamation case settlement). At the same time, the accusations against him haven’t been disproved, and Sono hasn’t made a film since the 2021 Nicolas Cage starrer “Prisoners of the Ghostland.”

Related to Best Japanese Horror Films – The Monstrous Feminine: 30 Best Feminist Horror Movies of All Time

18. Noroi: The Curse (2005)

Koji Shiraishi’s “Noroi,” rather than following the well-established J-horror tropes, uses the found footage/mockumentary narrative texture of “Blair Witch Project.” While I often find the shaky-cam realism of found footage horrors nauseating, “Noroi” is packed with enough eerie mysteries and genuine scares. The film revolves around Masafumi Kobayashi (Jin Muraki), a middle-aged journalist with an interest in chronicling supernatural incidents. His investigation begins with the complaint of a single mother about her creepy next-door neighbor. Eventually, it puts Kobayashi on the path to confront an ancient demon known as Kagutaba.

Apart from Kobayashi’s on-camera inquiries, “Noroi” also uses news excerpts, TV show clips, and archival footage to build the mystery and lore of Kagutaba from various angles. Even if we dismiss the irrational phenomenon in “Noroi,” it captures the recognizable horrors of modern human life. From loneliness and displacement to mental illness and suicide, the paranormal story takes us through the vulnerable populace of society. It’s as if the easy explanation of occult and demonic activity feels less unsettling than the true darkness engulfing these characters.

Writer/director Koji Shiraishi followed up “Noroi” with another found-footage horror, “Occult.” He has also made vengeful ghost tales—“The Slit-Mouthed Woman” and “Sadako vs. Kayako.” Yet the doomed documentarian’s pursuit of truth in “Noroi” remains the prolific horror filmmaker’s best work.

19. Cold Fish (2010)

While Sion Sono has always been a fearless filmmaker, the three relatively realistic and understated works – “Love Exposure,” “Cold Fish,” and “Himizu” – he made between 2008 and 2011 remain the peak phase of his career. Familial dysfunction is one of the staple elements of Sono’s works. But in “Cold Fish,” he dramatizes the dysfunction to a whole new level of terror. Loosely based on a true story, the film revolves around the meek Nobuyuki Shamoto, the owner of a small tropical fish store. He runs the shop with his wife, Taeko. Shamoto’s teenage daughter, Mitsuko, is going through a phase of rebellion, and she doesn’t get along with her stepmother, Taeko.

The family’s ordinary life is uprooted when they meet a seemingly gregarious Murata, who also owns a tropical fish store. Murata’s forceful personality pulls Shamoto into a business deal with him. Soon, Shamoto’s inability to confront people makes him a partner in Murata’s sinister plans. The nastiest surprises Sono springs upon us are best left undescribed. It’s definitely a lot to stomach as Sono unflinchingly visualizes the worst of humanity. The deliberately detached tone with which Sono captures the descent into madness also boasts some dark humor. The performances are flawless, particularly from comedian Denden as the beastly Murata.

20. Kotoko (2011)

Shin’ya Tsukamoto has a gift for making disturbing psycho-horrors about isolated individuals. However, unlike the graphic depravity of “Tetsuo: The Iron Man,” “Kotoko,” despite its overwhelmingly disorienting atmosphere, directs an empathic gaze at the titular mentally ill single mother character. Singer Cocco – who has also written the original story – plays Kotoko, who suffers from ‘double vision.’ She encounters different ordinary people in her everyday life, but in Kotoko’s perception, they are often accompanied by aggressive doppelgangers. Unable to perceive which is real, Kotoko puts herself and her infant son, Daijiro, in danger.

Like “Clean, Shaven” (1993) and “Spider” (2002), “Kotoko” brilliantly captures the spiraling down psychological state of its protagonist. At the same time, Tsukamoto is even more uncompromising and unnerving as he traps us in the headspace of Kotoko, making us genuinely feel the unreliability of her reality. Each of the erratically staged attacks on Kotoko by her phantom harassers grows so alarming that we seek respite from this panicked perspective. There are a lot of emotionally draining moments in the film, and it deals with a taboo subject (kids in distress), so it won’t work for everyone.

Nevertheless, “Kotoko” offers more than a horror movie experience. It showcases unbridled compassion for its troubled central character. Cocco’s incredible and fearless performance perfectly realizes Kotoko’s emotionally and psychologically complex journey.

Related to Best Japanese Horror Films: 20 Underrated Horror Movies of the 2010s

Honorable Mentions:

Jigoku (1960)

Nobuo Nakagawa is a prolific Japanese filmmaker who has worked in the industry since the late 1930s. But he was best known for his atmospheric horror films made between the late 1950s and the 1960s. Nakagawa was particularly successful with vengeful ghost movies like “The Ghost of Kasane Swamp” (1957), “Black Cat Mansion” (1958), and “The Ghost of Yotsuya” (1959). However, the filmmaker’s most ambitious work in the horror genre was the harrowing feast of brutality, “Jigoku” (“The Sinners of Hell”). Drawing from the Buddhist ideas of various realms of hell, Nakagawa assembles a group of sinners, recklessly committing sins such as murder, corruption, and deceit.

“Jigoku” is primarily centered on theology student Shiro Shimizu, who is engaged to his professor’s adorable daughter. But the feeble-minded Shiro’s fate is doomed when he goes out with his cynical friend, Tamura. Shiro’s strange journey puts him in contact with many degenerate individuals, who all eventually reach their destination of Hell. While the first half of “Jigoku” unfolds in a conventional manner, the latter half plays out like an extremely vivid nightmare, full of lurid and grotesque imagery. “Jigoku” was remade two times in 1979 (by Tatsumi Kumashiro) and 1999 (by Teruo Ishii), but the 1960 original is the most striking version of this fantasy horror morality tale.

Horrors of Malformed Men (1969)

Notorious cult filmmaker and pioneer of the Pink Film Movement, Teruo Ishii co-wrote and directed this utterly grotesque and bizarre horror. “Horrors of Malformed Men” can seem like a twisted adaptation of H.G. Wells’ 1896 novel “The Island of Dr. Moreau.” But this wacky fever dream is actually a joint adaptation of two of Edogawa Rampo’s tales – “Strange Tale of Panorama Island” and “The Demon of Lonely Isle.” Rampo is known as the father of Japanese mystery fiction and also the ‘master of macabre’ diffused with an abundance of Freudian overtones.

“Horrors of Malformed Men” is a film of two parts. The first half is a robust mystery tale with a rich atmosphere. It follows Hirosuke (Teruo Yoshida), who escapes from a mental asylum only to be framed for a murder he didn’t commit. While on the run, he assumes the identity of his recently deceased doppelganger, Genzaburo. Although Hirosuke gradually adjusts to his new life, the strange happenings in the household and the pull of a mysterious nearby island take him on a journey to meet Genzaburo’s unhinged father, Jogoro (Tatsumi Hijikata). The disturbing yet campy nature of the horrors portrayed in the second half discards the narrative-driven approach of the first half.

The dated yet frequently baffling journey into Jogoro’s deformed community scales the peaks of uncanniness. The absurdity and ickiness of the narrative will not work for those expecting a traditional horror narrative.