The French filmmaker Robert Bresson is recognized as one of the pioneers of the so-called minimalist transcendental style of European filmmaking, his approach rejecting almost all classical conventions in favor of an aesthetic that emphasized restraint, subtlety, and spiritual depth. Robert Bresson’s movies, characterized by their stark realism and austere beauty, invite viewers into an introspective journey that fundamentally challenges and, with some luck, transforms their perceptions of what the cinematic medium can achieve. Bresson operated from a singularly uncompromising artistic philosophy that sought to strip away the extraneous, the melodramatic, and the overtly dramatized, leaving only the barest essentials of image, sound, and elemental human behavior.

On a surface level, his filmic parables can seem characterized by their austerity – the cold whisper of dialogue, the protracted silences, the static camerawork that foregoes virtuosic showmanship in favor of an almost sculptural appreciation for detail and framing. Yet this rigorous formalism is always in service of something grander: evoking whole universes of implication, hinting at philosophical and spiritual dimensions that mainstream cinema could scarcely even approach. From his Catholic-steeped masterpieces like “Diary of a Country Priest” to the despairing modern alienation of “A Gentle Woman,” Bresson’s works operate on parallel planes of engagement – meticulous character studies grounded in sociological authenticity while simultaneously radiating with allegorical and metaphysical significance. He elevated the humblest surfaces to portals of existential and theological revelation.

In an era saturated with fast-paced, high-octane entertainment, Bresson’s films offer a contemplative respite, a chance to engage with cinematography as an art form that speaks to the soul. Bresson’s emphasis on the interiority of his characters and his minimalist approach challenge contemporary audiences to slow down and absorb the subtle, often overlooked nuances of human experience: his body of work forms a cinematic landscape that is both stark and richly textured, a testament to the enduring power of simplicity and the profound impact of a single unembellished image. To enter the hermetic worlds he constructs through arcane artistry and sheer ascetic force of will is to encounter the sacred made cinematically and profoundly manifest. In this article, we explore the ten best movies from the filmography of Robert Bresson.

“Cinema is the art of showing nothing.”

10. The Trial of Joan of Arc (1962)

Bresson’s cinematic retelling of the trial and execution of Joan of Arc represents the historical event with his distinctive minimalist style. It stands out, amongst other things, for its rigorous attention to authenticity, as Bresson used actual transcripts from Joan’s 1431 trial to craft the screenplay. The film opens with Joan of Arc (Florence Delay), captured by the English, facing a court of clerics and noblemen who aim to convict her of heresy. Joan remains resolute and unyielding from the start, displaying an unwavering commitment to her divine mission. As the trial progresses, she faces intense scrutiny and psychological manipulation from her inquisitors. Despite the pressure to recant her claims of divine guidance, Joan maintains her faith, even as her physical and mental strength is tested.

Bresson’s approach contrasts sharply with earlier and more conventional portrayals of the titular figure, such as Carl Theodor Dreyer’s “The Passion of Joan of Arc” (1928). While Dreyer’s film is renowned for its expressive close-ups and emotional intensity, Bresson’s is marked by its detachment, narrative economy, and rigor. His restrained visual style – characterized by static shots, minimal camera movement, and sparse music – heightens the gravity of the proceedings and draws the audience’s focus to the spoken word and the actors’ performances. Also notable is the way Bresson uses sound. The silence between pronouncements is heavy with tension, while the rhythmic scraping of quills on parchment becomes a constant, oppressive counterpoint to the dialogue. When Joan’s voice finally cracks, pleading for her life, the effect is all the more devastating for its very rarity.

9. A Gentle Woman (1969)

Bresson’s first feature in color adapts Fyodor Dostoevsky’s 1876 short story “A Gentle Creature,” following a beautiful and enigmatic woman (Dominique Sanda) forced into a loveless marriage with a pawnbroker, her hopes and dreams slowly crushed by the banalities of domestic life. Like much of the French master’s work, the film strips away conventional narrative trappings to lay bare the profound sadness and struggle at the heart of its seemingly mundane and deceptively simple story. It opens with a tragic scene: the young woman has just killed herself by jumping out of her apartment window. The rest of the film unfolds in flashbacks narrated by her husband, who stands by her body, recounting their relationship and the events leading to her death.

Sanda’s wide, unblinking stare speaks volumes about her character’s despair, while her husband – portrayed with a sort of oblivious callousness by Guy Frangin – drifts through life utterly disconnected from his wife’s inner turmoil. Like sculptors chiseling away at a block of marble, Bresson and his cinematographer employ a radical economy of style, each shot pared down to its essence. Events unspool not in a straightforward, cause-and-effect manner but as a series of isolated moments and images that require active participation from the viewer to become laden with meaning. An empty apartment, a potted plant gathering dust on a sill, the rhythmic ticking of a clock – these seemingly banal details take on the most profound significance in Bresson’s deft hands.

8. Diary of a Country Priest (1951)

With his third feature, “Diary of a Country Priest,” Bresson’s craft matures into his own as he ditches the professional actors and melodramatic dialogue utilized in his first two films. An austere and deeply moving adaptation of Georges Bernanos’ novel, the film portrays the spiritual journey of a young, ailing priest assigned to a rural parish in France, highlighting themes of faith, suffering, and existential angst. Brilliantly portrayed by Claude Laydu, the priest is newly appointed to a small, impoverished parish in the village of Ambricourt. He is eager to serve his parishioners but only encounters resistance and indifference from the villagers, as his attempts to connect with the local community are met with suspicion and hostility, exacerbating his feelings of isolation.

The film unfolds through the titled diary entries of its protagonist, allowing the viewer an intimate window into his psyche as he ministers to his flock. A wealthy Countess (Rachel Bérendt) seeks spiritual guidance from the priest, but her troubled past and emotional volatility leave him questioning his own ability to offer solace. Whispers of scandal and accusations of impropriety further erode his already fragile sense of self-worth. Laydu’s pale, hollow-cheeked features and the tremulous fragility of his performance perfectly embody the character’s physical and spiritual decrepitude. We see him wheezing his way up hills, bowed under the weight of his vocation, yet soldiering on with quiet determination. The saintly Laydu’s steadfast humility in the face of mockery, failure, and even violence becomes almost Christ-like in its sacrificial resonance.

7. Lancelot of the Lake (1974)

A somber and introspective take on the Arthurian legends, “Lancelot du Lac” features Bresson’s exploration of the disillusionment and decay of chivalric ideals through the story of Lancelot (Luc Simon), his illicit love for Queen Guinevere (Laura Duke Condominas), and the ultimate disintegration of the Round Table. What in lesser hands could have devolved into mere melodrama becomes, through Bresson’s signature minimalism, a contemplative allegory about desire, guilt, and the struggle between duty and passion. Gone are the elaborate courtly dances and grand pronouncements of love, while the dialogue is sparse and clipped – delivered in a monotone that underscores the characters’ emotional detachment. Lancelot’s attempts to reconnect with his fellow knights and regain his honor are thwarted by his lingering feelings for Guinevere and the growing animosity from other knights, particularly Sir Gawain (Humbert Balsan).

Bresson had noted how he’d designed “The Trial of Joan of Arc” (1962) to be “made entirely out of questions and answers,” the back-and-forth nature of Jeanne’s interrogation almost resembling the rhythm of swordplay. The same blows and parries return in “Lancelot” – in a more literal fashion – and yet they do so predominantly through the soundtrack, even as the image track isolates and juxtaposes their sources synecdoche-like.

It was one of the key ways that Bresson sought to draw from poetry, alongside the suggestive nature of the verse, the same way he draws from Arthurian legends to lead us along Lancelot’s “very particular inner adventure” while using the subject matter as a mere pretext. Events unfold through a series of isolated, elided moments and symbolic imagery – a bloodied gauntlet lying in tall grass, a heavy iron gate closing on a shadowy rendezvous. Like the greatest choreographic works, entire emotional arcs are conveyed almost entirely through the physical vocabularies of bodies in motion.

6. Pickpocket (1959)

“Pickpocket” centers on Michel (Martin LaSalle), a disaffected young man living in Paris whose social estrangement and existential angst result in him turning to pickpocketing, if only as a means of asserting his agency over the world around him. Brought to life through a series of elliptical scenes eschewing traditional psychology and melodrama, Michel’s inner life is rendered not through histrionics but the smallest gestures and facial tics. A sideways furtive glance, hands nervously fidgeting in pockets, speaks volumes about his profound alienation from the world around him. Despite his criminal activities, Michel maintains a complicated relationship with Jeanne (Marika Green) – a neighbor taking care of his mother – who embodies a sense of purity and goodness that starkly contrasts with his own moral ambiguity.

As the film’s prefatory scroll informs us, this isn’t a police thriller by any means but rather the singular journey of one highly idiosyncratic soul struggling to escape the prison he has created for himself. The pickpocketing set pieces themselves unfold with the taut precision of magic acts, the camera’s merciless gaze drinking in every subtle motion of fingers sliding into jackets and wallets smoothly extracted. Like Bresson’s previous film, “A Man Escaped” (1956), there’s no single discernible antagonist in “Pickpocket.” But whereas Fontaine was up against the shackles of prison and an imminent death sentence, Michel’s prime source of conflict arises from within himself. Caught between his philosophical trappings willing him towards a needless life of crime and his well-meaning friends and family, Michel drifts along toward what seems to be his destined fate: simultaneously of his creation but also beyond his control.

Also Related to Robert Bresson’s Movies: 10 Great Films That Helped Cinema Grow As An Art Form

5. The Devil, Probably (1977)

As a haunting exploration of metaphysical drift and the search for meaning in a seemingly meaningless world, “Le Diable Probablement” represents both a thematic and stylistic culmination of Robert Bresson’s transcendental artistic vision. The loose narrative follows Charles (Antoine Monnier), a privileged yet deeply troubled young man adrift in a turbulent Paris of political unrest and generational ennui. Withdrawn into himself, he drifts from one vacant relationship and aimless pursuit to the next, increasingly given to fits of despair and even self-destructive impulses. Bresson’s radically fragmented approach renders Charles’ inner life in oblique shards and jagged edges rather than any conventional psychologizing. Each of his friends represents a different response to the modern world’s failings: some seek solace in political activism, others in religious devotion, while Charles himself remains detached and cynical, viewing all efforts as ultimately futile.

Charles’s alienation is mirrored in his relationship with his girlfriend Alberte (Tina Irissari) and his involvement with another woman named Edwige (Laetitia Carcano). Despite these connections, however, he remains emotionally distant, his interactions marked by a profound sense of boredom. As the narrative progresses, Charles’s despair deepens. He attends environmental protests and debates, but these activities only reinforce his sense of futility. Empty apartments, graffiti-scrawled bathroom stalls, and barren urban landscapes become expressionistic backdrops for the characters’ profound disconnect from themselves and their surroundings. Charles’s existential grappling, while colored by the angst of the late 70s zeitgeist, taps into something infinitely more universal and resonant about humankind’s eternal longing for meaning amidst the seeming absurdity of existence.

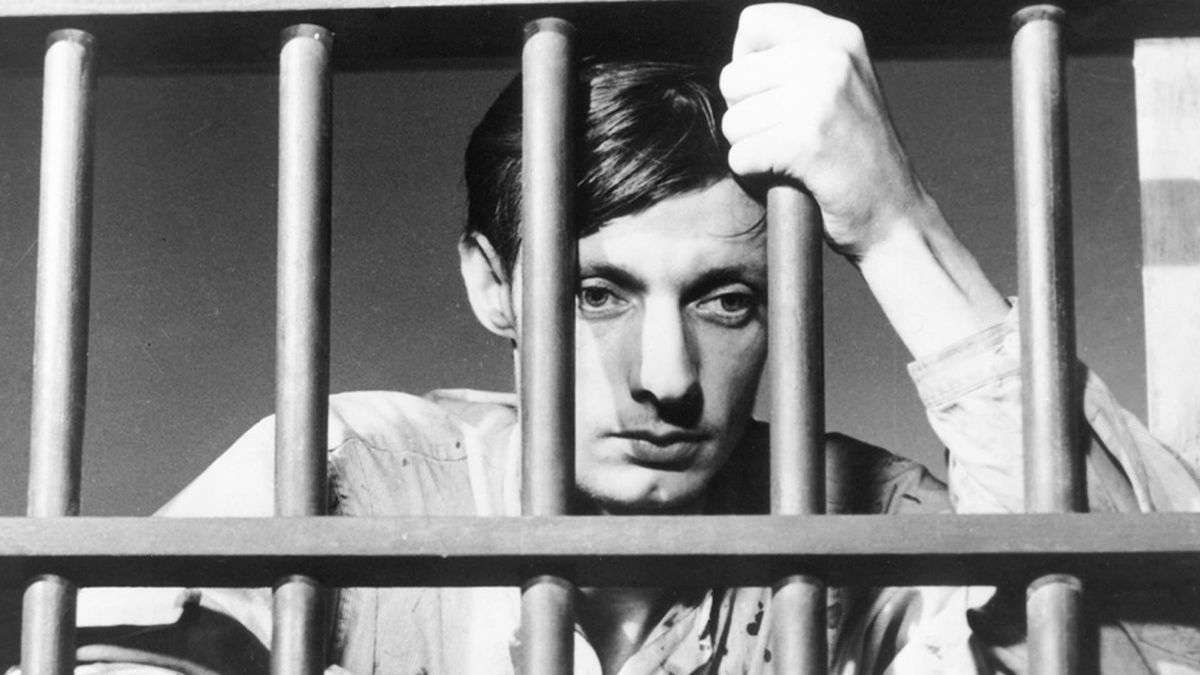

4. A Man Escaped (1956)

A riveting and meticulously crafted cinematic experience, “A Man Escaped” is based on the true story of André Devigny, a French Resistance fighter imprisoned by the Nazis during World War II. Ostensibly a spare, unadorned prison escape film, it transcends its humble genre trappings to become a profound philosophical and spiritual exploration of man’s capacity for liberation in even the most dire of circumstances. The film begins with Fontaine (François Leterrier), a member of the French Resistance, being captured by the Germans and taken to Montluc Prison in Lyon. Despite the heavy security and seemingly insurmountable odds, Fontaine remains determined to escape, and the narrative is driven by his meticulous planning and unwavering resolve.

By brazenly informing us of Fontaine’s fate at the very outset, Bresson ensures our full undivided attention on the method that gets him there, in yet another of his many visionary undertakings to purify and concentrate the cinematic experience. In the very first sequence, as Fontaine makes his first amateurish escape attempt, Bresson’s shrewd use of off-screen space is on full display, showing us the bare minimum and allowing the fertile power of our imagination to take over and piece together the rest.

By maintaining economy over the selection of shots and supplanting the usual dialogic exposition with a narrative voiceover that helps interiorize the protagonist’s emotions, Bresson ensures that every deliberate close-up pierces through the character’s psychological façade to devastating effect. Sound design plays a crucial role, with Bresson emphasizing diegetic sounds —the scraping of the spoon, the footsteps of guards, the clinking of metal, etc. This auditory focus immerses the viewer in Fontaine’s experience, making each sound a potential signal of danger or progress.

3. Mouchette (1967)

“Mouchette” is, to put it lightly, a harrowing plunge into the depths of human suffering and spiritual desolation. Adapted from Georges Bernanos’ novel, the film presents a bleak yet deeply humanistic portrait of its titular character, a young girl drowning in a sea of poverty, neglect, and disillusionment. Mouchette is a fourteen-year-old girl whose life is marked by a series of hardships: her father is an abusive alcoholic, her mother is terminally ill, and she bears the burden of caring for her baby brother. At school, she faces relentless bullying, further compounding her sense of isolation. The narrative unfolds with Mouchette encountering various village inhabitants who each, in their own way, contribute to her misery.

One night, while hiding in the forest during a storm, she meets Arsène (Jean-Claude Guilbert), a poacher who has just fought with another man named Mathieu (Jean Vimenet). Arsène coerces Mouchette into assisting him, and their interaction culminates in a scene where he takes advantage of her vulnerability, leaving her even more despondent. “Mouchette” takes forward Bresson’s treatment of the cruelty pervading this world, precipitated by the fallen nature of man and its primary victims: the young, the weak, the penniless, and the voiceless. As with everything else, political subtext in Bresson’s films has never been an element to call attention to itself, always hanging loosely around or simmering underneath the blank facial canvasses of his models. Muddied paths, leafless trees, and the perpetual drizzle of rain become metaphors for Mouchette’s emotional desolation – her inner and outer landscapes merging into one.

2. Au Hasard Balthazar (1966)

Bresson’s masterful take on Dostoevsky’s “The Idiot,” “Au Hasard Balthazar,” renders an alternately brutal and beatific portrait of rural French existence through the metaphoric gaze of a donkey. On its surface, the plotline traces Balthazar’s travels from owner to owner, each episode charting the animal’s oscillating fates between kindness and cruel mistreatment at the hands of the peasant farmers, drifters, and children who briefly enter his orbit. The story begins with Balthazar as a foal, tenderly cared for by a young girl named Marie (Anne Wiazemsky) and her family in a rural French village. Balthazar’s early days are filled with gentle affection, but this period of innocence can only be short-lived.

As Balthazar matures, he is sold to a series of owners who treat him with varying degrees of neglect and brutality, as his story intertwines with that of Marie, the latter’s own life becoming increasingly troubled. Marie’s father (Philippe Asselin) falls into debt, leading to the family’s downfall and Marie’s subsequent abuse at the hands of various men, including the sadistic Gérard (François Lafarge).

Throughout the film, Balthazar is subjected to harsh labor, mistreatment, and exploitation, mirroring the plights of those around him. Despite his suffering, or perhaps because of it, Balthazar remains a symbol of purity and endurance – his silence and stoicism reflect a Christ-like acceptance of his fate. Bresson’s radical minimalism is here coupled with an intricate deployment of symbolism and metaphor, as Balthazar assumes the dimensions of a quasi-mystic avatar, his journey a parable for the vicissitudes of mortal existence and humankind’s relentless quest for transcendental meaning in the very face of banal suffering.

1. L’Argent (1983)

“O money, God incarnate, what wouldn’t we do for you?”

The final film in Robert Bresson’s career, the formal and thematic culmination of a lifetime of cinematographic experimentation, stands as a potent critique of the corrupting power of money and the moral decay it engenders. Based loosely on Leo Tolstoy’s 1911 novella “The Forged Coupon,” “L’Argent” is a meticulously crafted exploration of how a single counterfeit bill cascades through society, leaving a trail of devastation in its wake. The narrative takes off with a schoolboy named Norbert (Marc Ernest Fourneau) who, needing money, passes a forged 500-franc note at a photography shop. The shop owners realize the bill is fake and, in turn, decide to use it to pay their fuel deliveryman, Yvon Targe (Christian Patey), rather than incur a loss.

Unaware of the note’s illegitimacy, Yvon attempts to use it at a restaurant, where he is arrested for fraud, following which Yvon’s life begins to unravel, soon sending him on an embittered spree of violence. Bresson’s radical approach to editing and sound design is seen here, marshaling silence, ambient noise, and mere snippets of jarring, contextless music into a modernist symphony of profound spiritual expression. In the absence of a musical score, the clinking of coins, the rustle of bills, and the ambient noises of the urban environment are all amplified to underscore the omnipresent influence of money. A fitting swan song for the legendary French director, “L’Argent” distills Bresson’s transcendental aesthetic to its most rigorously pared-down essence, laying bare the corrosive effects of greed and human indifference with an almost biblical sense of cosmic reckoning.