Takeshi Kitano: A Multifaceted Filmmaker

Takeshi Kitano is an inscrutable filmmaker with some exceptional movies in his kitty. On the one hand, his experimentation with form and bizarre mixture of slapstick humor, sentimentality, and violence transcends the inherent nature of the generic narrative, foregrounding the humanity and absurdity of his characters. On the other hand, he can entirely stay away from the genre elements to depict the ordinary lives of Japanese, enveloped in a state of quietude; the essential ‘Japanese-ness’ – what’s believed to denote the uniqueness of Japan’s cultural and national identity – is sublimely evoked which is often felt in the cinema of Kenji Mizoguchi, Yasujiro Ozu, and Mikio Naruse. “My primary activity is trying to avoid being pigeon-holed by the public”, Mr. Kitano states. The internationally celebrated, multi-talented artist has perfectly carried out that activity.

In the 2003 Guardian article, Takeshi Kitano is called an ‘a one-man cultural industry’, hinting at the many avatars he has taken over the years apart from being an actor and director. One could say Kitano became a very good film-maker by accident. I mean a real accident. In 1994, Kitano was seriously injured due to a motorcycle accident. The near-fatal crash left his face partially paralyzed, making him more intimidating to play those tough-guy roles. He also took up painting after the accident, his brush works are not only seen in his films but also were exhibited in Paris art galleries.

Related to Takeshi Kitano: Every Quentin Tarantino Film Ranked

The Artistic Versatility of Takeshi Kitano

By delicately describing Takeshi Kitano’s movies as a ‘very acquired taste’, one could expect him to be an obscure artist, familiar only in the arthouse circles. But Kitano is a huge star in Japan. In fact, he is ‘Beat’ Takashi, the iconic television personality and wisecracker. His comedic routines are borrowed chiefly from Japanese comic traditions known as ‘Manzai’. Critics would assert that Takeshi Kitano the film-maker is perpetually involved in a battle with his alter-ego, ‘Beat’ Takeshi. As if the film-maker Kitano is trying to deconstruct the image of TV star Kitano. Moreover, Kitano himself has said in an interview after the success of Hana-Bi (1997), “Whenever I appeared on screen, audiences would start laughing no matter what role I was in. It took about 15 years for audiences to regard me as something other than a comedian.”

Takeshi Kitano’s Cinematic Journey

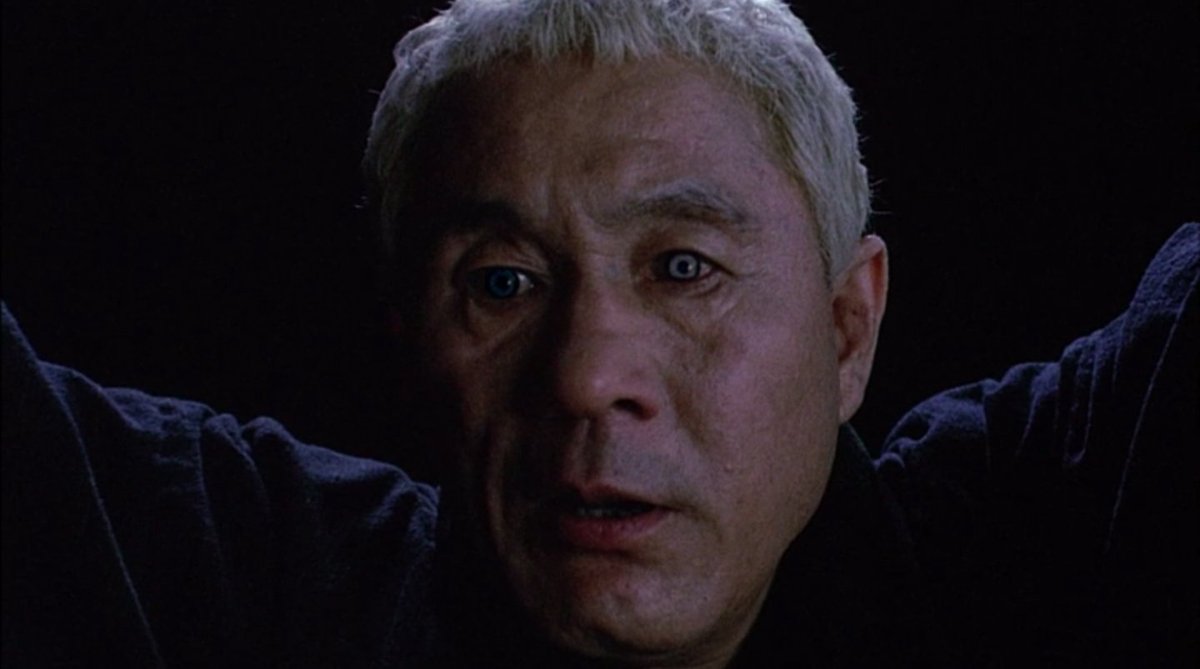

Takeshi Kitano started acting in movies and TV from the early 1980s, his first famous role was playing Sergeant Hara, a guard at the prisoner-of-war camp in Nagisa Oshima’s Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence (1983). In 1989, Takeshi Kitano directed his first film titled ‘Violent Cop’ after the veteran Japanese film-maker Kinji Fukasaku left the project. He also played the titular role; the cool-headedness and stoicism on display here set the tone for his future cops & yakuza roles. The film also marked Kitano’s first creative collaboration with popular music composer Joe Hisaishi. Violent Cop was a critical and commercial success, but his subsequent films (in which he nurtured his distinctive style) didn’t earn much.

After directing and acting in a film about a sociopathic gangster (Boiling Point), Kitano surprised cineastes by making a very emotionally delicate film (A Scene at the Sea), devoid of his trademark bursts of violence. Sonatine (1993) was about an expelled gang boss, full of existential musings. Quentin Tarantino was so impressed by the movie that he released it on his own DVD label. It was screened in the Un Certain Regard section of the Cannes Festival although it was a commercial flop. Two films later, Takeshi Kitano achieved great international success as his Hana-Bi (‘Fireworks’) won the Golden Lion Award at Venice Film Festival.

While Kitano’s first English film (Brother, 2000) is generally regarded as a blunder, he reaped huge commercial success with the 2003 reboot of famous fictional lone swordsman character, Zatoichi. Before directing Zatoichi, Takeshi Kitano also made the visually sumptuous Dolls (2002). He followed it up with a trio of (overly) self-indulgent, surrealist semi-autobiographical sketches: Takeshis’ (2005), Glory to the Filmmaker (2007), and Achilles and the Tortoise (2008). The last work in this trilogy is watchable, whereas the other two are very disappointing (same as his last four crime/dramas which was nothing but a stale recycling of his familiar tropes).

As a viewer who hasn’t directly experienced Kitano’s different personas on Japanese TV or due to possessing only a little knowledge about the Japanese culture, I find it a bit harder to interpret his works. Personal references could only be gleaned after going through various articles. Yet what I love about Kitano’s directorial projects is the way his formal austerity is tempered with a humanist fondness for the damaged, alienated characters. Similar to the works of any great minimalist film-maker, Takeshi Kitano could magnificently express the spiritual state of his characters without utilising the usual dramatic languages of cinema.

5. A Scene at the Sea (1991)

This sublime feature about a deaf-mute young man obsessed with a surfboard is sandwiched between two of Takeshi Kitano’s mediocre works. One is a freewheeling gangster feature (‘Boiling Point’), and the other is a confounding slapstick comedy (‘Getting Any?’). A Scene at the Sea is a film of stillness, a snapshot of the idyllic that it’s hard to grasp Takeshi Kitano could be this lyrical.

The narrative revolves around Shigeru (Claude Maki), a deaf-mute trash collector. After coming across a discarded surfboard, Shigeru finds himself drawn toward the sea, who is also accompanied by his deaf girlfriend Takako (Hiroko Oshima). The introspective youngsters’ effort to escape the drudgeries of daily life only invites ridicule from the hipsters surfing the beach. Their perseverance, however, wins the surfers’ respect. The drama might be slight and the narrative virtually unfolds wordlessly (Joe Hisaishi’s score fills in the emotions), but the minimalistic style bestows a transcendental appeal to the movie. Kitano’s ability to weave poetic dramas without gratuitous violence was also evident in his later works, Kids Return (1996) and Dolls (2002) – also films in which he didn’t act.

4. Zatoichi (2003)

It would be hard to recreate the magic of a franchise that’s as legendary as the Zatoichi series of films. The illustrious star Shintaro Katsu played the role of crafty blind masseur and master swordsman between 1962 and 1989 in 26 films. Takeshi Kitano’s version perfectly captures the essence of the original films while also withholding the essential, idiosyncratic Kitano-esque elements.

Set in post-feudal Japan, the enigmatic and taciturn Zatoichi arrives at a town menaced by two warring yakuza factions. One of the gangs has hired a ronin named Hattori (Tadanobu Asano) who is desperate for money to treat his ailing wife. Naturally, Zatoichi finds himself drawn into these conflicts as he puts his cane sword to fitting use. Full of brilliant action sequences, interleaved with contemplative and quirky segments, this is Kitano’s most entertaining feature.

Also, Read: The Tale of Zatoichi [1962]

3. Kikujiro (1999)

Kikujiro’s plot is so minimal. Nine-year-old Masao (Yusuke Sekiguchi) has no father, and never met his mother who is supposedly working far away. He lives with his grandmother and the sad-faced boy comes across his mother’s address. With little money and no idea how far the place is, the kid embarks on a journey. But when the boy is ambushed by some hoods, he is rescued by one of his grandmother’s friends. She then asks her no-good husband, ‘Kikujiro’ (Takeshi Kitano) to take Masao to his mother. Although it sounds like a very sentimental road-movie, Kikujiro reflects Kitano’s worldview and retains his formal rigor.

Apart from one strange sequence with a pederast, the narrative virtually has no violence or dramatic tension. It is sentimental, but also contains the atypical Kitano-esque elements – the frozen stance, blank stares, absurdly funny physical gags, etc. Despite quixotic digressions, the film gracefully points to the trauma of growing up without a mother. Bolstered by Joe Hisaishi’s bewitching score, Kikujiro is a low-key comedy suffused with melancholy.

2. Sonatine (1993)

Sonatine turned Takeshi Kitano from being a ubiquitous Japanese celebrity to a well-regarded cultural export. Though a commercial failure, the film brought him international attention. Kitano plays Murakawa, a yakuza embroiled in inter-gang warfare. The world-weary Murakawa looking for a way out is approached to settle a dispute involving an allied gang in Okinawa.

When he and his gang members get caught in the crossfire, they simply take up a seaside residence. The film is a deconstruction of sorts on the yakuza genre with Murakawa’s intents and demeanor are constantly kept opaque. It really shows some unexplored facets of a gangster lifestyle, disclosing the myths surrounding their masculinity and alleged bravado.

Also, Read: Sonatine: Ingenious Mobster Cinema

1. Hana-Bi (1997)

This film that was included in Akira Kurosawa’s 100 favorite movies is the thematically and aesthetically strongest work from Takeshi Kitano. In Hana-Bi (Fireworks), he plays a hardened cop named Nishi, who has lost a child and his wife (Kayoko Kishimoto) is dying of leukemia. Adding to the woes, a stakeout operation goes wrong as Nishi’s younger partner is killed while another colleague/friend, Det. Horibr is grievously wounded. Nishi is also pursued by the yakuza for unpaid debts. In a sub-plot, the now wheel-chair bound Horibe (Ren Osugi) takes up painting on Nishi’s insistence (Kitano’s own dazzling paintings during his rest after the near-fatal accident appears throughout these parts).

Also, Read – Hana-Bi [1997]: The Meditative Trip of a Beleaguered Detective

Hana-Bi proves to be the most balanced juxtaposition of Kitano’s elements: extreme tenderness and harsh violence lays side by side. Takeshi Kitano keeps getting at two visual motifs: the flowers and fireworks, the obvious meaning of both is conveyed through unique aesthetic expressions. With a plot that’s so mundane, but a form that’s richly experimental, Hana-Bi is Takeshi Kitano’s most affecting cinema.