Though the ‘Femme Fatale‘ archetype existed in popular culture long before cinema, it is deeply associated with film noir. To understand why the archetype is tied to the roots of film noir, we must first define noir itself. The primary debate surrounding film noir is whether it is a genre or style. In fact, examining its history makes the debate grow ever stronger and the solution murkier, fitting for film noir and its aesthetic origins. As such, it’s appropriate Noir takes its name from the French term for Black/Dark Film. Film Noir generally uses low-key lighting and absurd shot composition to enhance the effect of its black-and-white pictures.

The German Expressionist movement, from which many Film Noir filmmakers hailed, influenced this stylistic choice. These filmmakers brought their sensibilities to Hollywood when emigrating at the height of World War II. Subsequently, the Second World War played a profound role in creating film noir and, in turn, the role of the femme fatale. Post-war sentiment was rife with paranoia and disillusionment. Men returned from the battlefield weary and uncertain of their place in a changed landscape. Many such men would go on to write hardboiled fiction with dashes of pessimism at their core. These novels formed the basis, directly and indirectly, for film noir cinema.

Film Noir was a term given retroactively to these pictures; more akin to melodramas produced from the 1940s to the 1950s (and then some). These films delved into the disrupted psyche of men and the nation but didn’t leave women behind that formed the fabric of society. Women at the height of the Second World War found a new sense of liberation. As men left for war, women were thrust into the workforce to fill their roles. For a patriarchal society, it was deemed natural that after the war, women would collectively choose to return home and resume their perceived roles within the order. Yet the adverse effect of this liberation gave birth to a rising sentiment and the first hints towards the feminist movement.

As such, popular culture caught on to this destabilized order; from hard-boiled fiction to Film Noir, the Femme Fatale was born as a reactionary creation of this newly liberated female populace. The Femme Fatale is essentially characterized as a seductress, a woman who uses her feminine wiles and sexuality to navigate the crime-riddled world of men. In the heyday of the restrictive Hays Code, her actions were mostly implied, but her death was inevitable to restore the moral code of society. This ultimately meant that even if the predominantly male protagonist didn’t pay for their crimes, the femme fatale surely would for crossing the boundaries of gender expectations.

In retrospect and further analysis, the femme fatale has become an intriguing figure of both aspiration as well as a cautionary tale. In turn, Film Noir also created the space and nuanced discussion for other types of women, like the empowering figures straddling the line between good and evil. Even then, not every Film Noir from its era found the need to discuss and dissect the role of the Femme Fatale. Some found an even greater cynicism by omitting the role of women entirely from the picture. When one thinks of Film Noir, whether as a genre or style, the femme fatale in all her glory beside the hapless protagonist (usually a Detective) is what one thinks of.

This list highlights films that omit the archetypal role entirely or, in some cases, subvert viewers’ expectations during an era when films rarely trod this path. For brevity’s sake, the list has been curated to include films set specifically during the era designated as Film Noir, from the 1940s to the 1950s. As Cold War sentiment ramped up and paranoia took a whole new meaning, Neo-noir was born, and this isn’t the point of discussion for this list. Similarly, because the definition of film noir and femme fatale is up for debate, there may be omissions in the list made on a preferential basis.

For example, there is a healthy debate about whether Alfred Hitchcock’s cinema can be categorized as film noir. This confusion persists despite Hitchcock having no root or connection to the forbearers of noir. Alfred Hitchcock’s signature style often played on the fringes of the tropes that define the type of film. Femme fatales appear in varying categories, especially since some iconic ones balance the tightrope between being wildly rebellious and ultimately conforming to societal expectations. Some are even deemed fatal by the mere projection of the male gaze on them rather than by their own actions; for example, the iconic Laura (1944), whose titular character is an innocent victim but whose image projects the aura of the ideal femme fatale.

This alphabetically ranked list is by no means a definitive article on the subject. As classifications continue to be re-examined, experts are discovering more and more films of the era that fall under the distinction. As such, there are perhaps more film noirs lacking a Femme Fatale than those with them. These films are just ten of the greatest ones you will see.

1. In A Lonely Place (1950)

If film noir truly isn’t a genre, then a story of a doomed romance is no more tragic melodrama than any other. Nicholas Ray’s In a Lonely Place is one of the many iconic noirs set in the hollow glamour of Hollywood. Humphrey Bogart, a staple of Film Noir, plays trigger-tempered Dixon Steele. Steele is a famed screenwriter whose fatal flaw is he’s a man who doesn’t understand or tolerate people in a profession where knowing people is the game. His anger has a way of getting him into trouble, to the point that the Police peg him for the murder of a woman he barely knew.

Enter Laurel Gray (Gloria Grahame), a woman who could easily be his salvation if not for his temperament and the threat of death hanging over their love story. Hilariously, their first real meet-cute occurs amid the investigation at the Police Station. Gray and her desire to ascertain whether Steele is a killer eventually ruins their relationship.

Ray and his screenwriters are not interested in merely highlighting these characters in singular dimensions. Gray’s concern, as well as the ambivalence of Steele to the accusations against him, is mined for psychological depth. This is rarely seen in Film Noir narratives, which are concerned with plot over character. There’s the subtle thread of Dixon’s post-war trauma as well as Gray’s past relationships, which inform their individual issues with love and trust. Trust especially plays a key role; the theme becomes the driving force for a very thrilling narrative with a more romantic heart at its core. The dual protagonists are ultimately far too complex and mired in complication, ending, as the film title suggests, in a lonely place.

2. Key Largo (1948)

Reuniting the iconic pair of Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall after The Big Sleep (1946), Key Largo doesn’t have enough space for the couple’s witty repartee. Instead, Bacall is placed in the unrewarding role of war widow Nora Temple. Nora and her father-in-law run the Hotel Largo in Key Largo, Florida, where ex-soldier Frank McCloud (Humphrey Bogart) comes to visit. Unbeknownst to them, they are going to be set on both sides by a raging hurricane outside and trapped inside with notorious gangster Johnny Rocco (Edward G. Robinson). Rocco is a wanted man and in exile with his gang, set to make a deal that could return him back to prominence. The real duel for Bogart in this film is with Robinson’s antagonist, despite neither man’s desire to take undue action.

The dangers of nature thus act as an allegory for the narrative’s lack of concern over archetypes and the imminent doom of all in film noir. Survival plays a key theme generally in noir, reflected in the ironic lack of heroism within the celebrated Frank. Nora shows that Frank’s disillusionment from his past is a shunning of his duty to do right by his code. The only other female character in the proceedings is Gaye Dawn (Claire Trevor), an alcohol-addicted singer and lover of Rocco’s. Dawn is the reflection of the tragedy behind the Gangster’s Moll/Femme Fatale archetype as a woman used by society’s worst elements. It is Trevor’s riveting performance that really rounds out this adventure film tinged with the darkness of noir.

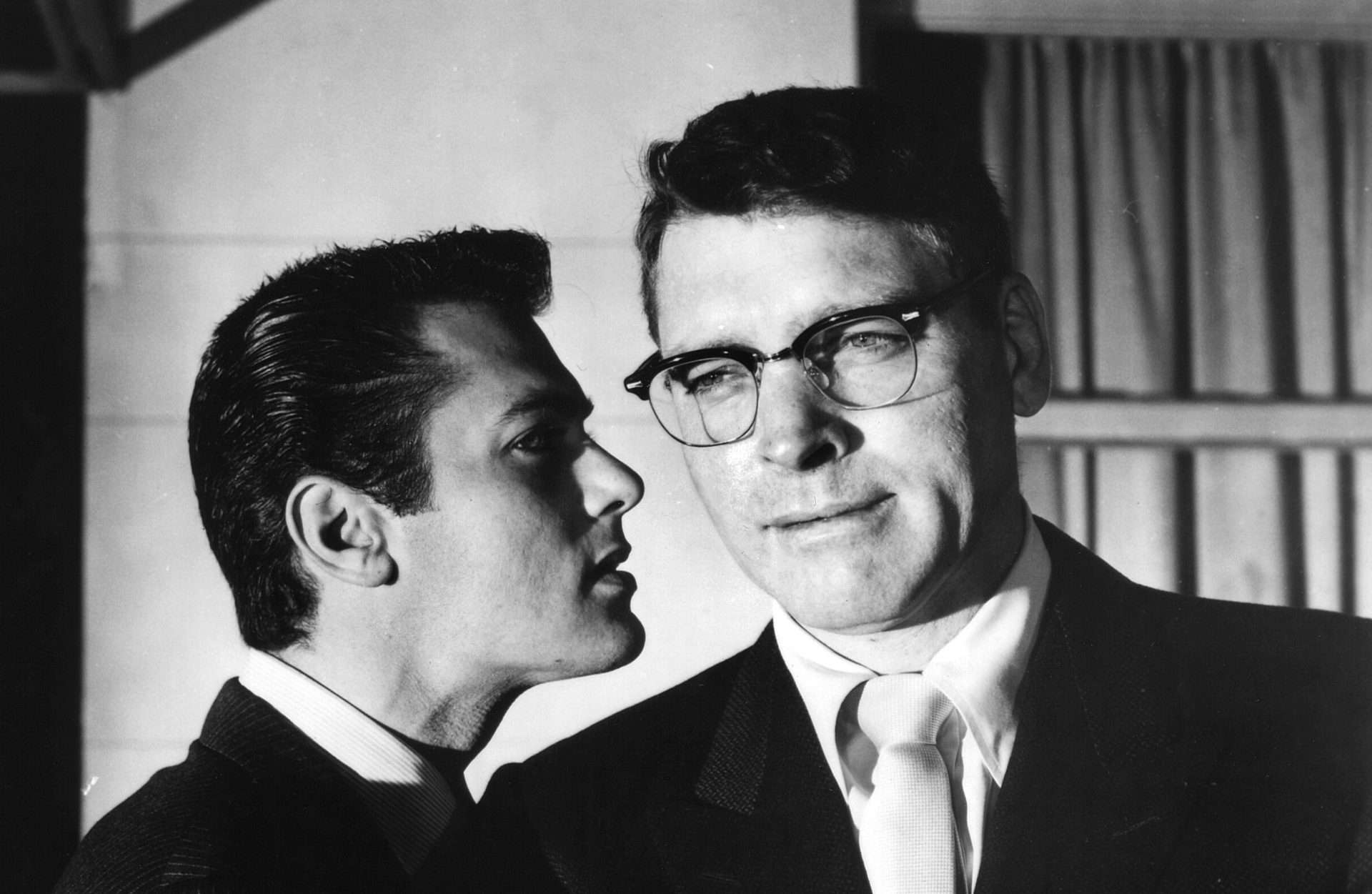

3. Sweet Smell of Success (1957)

Sidney Falco (Tony Curtis) is a slimy press agent desperately snaking his way up the media ladder for his clients and his own survival, knee-deep in the muck. JJ Hunsecker (Burt Lancaster) is a highly influential media columnist living well above the city’s muck that he exploits with his power. Both men are similar in nature: full of ego, ambition, and, ultimately, selfishness. Essentially, they play the role of the Homme Fatale (the gender-reversed Femme Fatale archetype). Yet they aren’t concerned with seducing as much as destroying others for their own benefit, especially the female lead. The female lead in question is Susan Hunsecker (Susan Harrison), JJ’s unwitting sister, very much in his thrall but slipping away slowly. She’s in love with a rising musician, and in the guise of concern, JJ uses his power over Sidney to help break them up.

Sweet Smell of Success is a fascinating media satire with sharp and economical writing that lays out the cruel nature of its lead characters. Classical noir filmmaking with shadowy frames turns this dramatic play into a delectable thriller in which the viewer witnesses how far men can fall for their desires. An edgy Jazz score packages all this, haunting the chess match both men play in order to enact their goal. It strums along right to its bittersweet climax, where the dark night of film noir is replaced by a new dawn for the empowerment and freedom of the feminine. This is a rare film noir that saves its female character instead of condemning her to the fate of her male counterparts.

4. The Bigamist (1953)

Infidelity is one of the major plot points that propel any excellent film noir. The best kind of temptress would be one who snatches a stable man from the ideal family life. In this scenario, The Bigamist befits this description as a family drama that unspools like a thriller when a man’s infidelity is uncovered. Despite playing within this narrative trope, what makes The Bigamist so fascinating is the lack of a femme fatale, or any archetype for that matter. In fact, the story and characters are rich with nuance. One could easily fail to categorize it as a film noir if it weren’t for the treatment. Thanks to its director and supporting actress, the writing is full of depth, sincerity, and empathy.

Ida Lupino remains a vital and unheralded filmmaker of her time, especially in film noir. The narrative unfolds through fragments of investigative flashbacks, primarily through the perspective of its male lead, Harry Graham (Edmund O’Brien). The film finds ways through Harry’s lens to empathize and scrutinize his actions. Harry falls for another woman, Phyllis Martin (Ida Lupino), after his wife, Eve Graham (Joan Fontaine), becomes too focused on their business instead of their relationship.

The film could have fallen into the commentary of showcasing the woman’s necessity to be the glue to hold the house together. Yet under Lupino’s dexterous direction, it unpeels greater layers of subversion. Harry’s unflinching narration paints him as the instigator of the entire dilemma, pushing his wife to work after they cannot conceive. Harry highlights his callous nature in not realizing her emotional turmoil or that of Phyllis, whom he leaves pregnant after their affair. Just as much a discussion on outdated, unfair gender norms, Lupino leaves space to fathom the protagonist’s predicament.

In contrast to most anti-heroes in film noir, the male character takes responsibility and ultimately comes out the better for it. Few films of the era could develop such dense and deep characters while somehow managing to package that in a tight, exciting plot. Moreover, few films of the era could find a justified balance in each of their characters’ actions, especially when noirs generally revel in one-dimensional archetypes. For crafting tension from such a complex dramatic scenario, Ida Lupino deserves to be revered as a master of film noir.

5. The Big Heat (1953)

Directed by Film Noir pioneer Fritz Lang, Big Heat is an investigative thriller starring Glenn Ford as Homicide Detective Dave Bannion. Dave’s curiosity about the suicide of a rouge officer spurs him into conflict with high-class criminal elements. Unraveling the twisted conspiracy and connections ultimately results in the death of his wife. It also brings him face to face with the deceased officer’s suspicious wife, Bertha Duncan (Jeanette Nolan), and Debby Marsh (Gloria Grahame), one of the gangster’s girlfriends. Vengeance is vital to the plot, and as with any film noir, it throws these characters headlong into a bittersweet aftermath. Though Ford’s character is the hero, his actions and demeanor, especially when using Debbie for the case, make him a Homme Fatale. Meanwhile, Debbie’s role walks that tightrope between the good and bad girl.

Twists and turns reveal Bertha’s own role in the death of her husband and her machinations that drive the central narrative. Yet none of these characters fully embody their archetypes. Bannion is clearly the typical anti-heroic figure in film noir. He isn’t manipulating the women in his pursuit of revenge, even though his cruelty has an indirect effect on them. Despite her styling and demeanor, Debbie shows far greater empathy for the suffering of others.

It is, in fact, a trait Debbie shares with Dave and fuels her desire to help him. She suffers for these actions at the hands of the antagonists. Finally, though Bertha is quite the villain, she doesn’t necessarily depict the classic Femme Fatale in any way. The plot machinations overwhelm the characters, yet Lang’s filmmaking remains as sharp as ever. He paints this sordid tale in the darkness one comes to expect of his German Expressionist influences.

Read More: The 25 Greatest Cannes Film Festival Palme d’Or Winners of All Time, Ranked

6. The Naked City (1948)

Opening with a narration highlighting that the film was entirely shot in New York, Naked City has more in common with a Police procedural than classic hardboiled fiction. This isn’t just seen in its setting on real locations but in the treatment that approaches the Police’s investigation like a docu-drama. The victim at the center of the case is naturally a woman. Meanwhile, those involved in solving it are primarily men. With a sensibility hewing closer to European cinema than film noir, Dassin takes a lax approach to the plot, diverting and diving into pockets of unrelated sequences. The characters solving the case fall into false traps and red herrings that lead nowhere.

Comical anecdotes are peppered throughout the film to break up the linear plot. The central case looms large over the narrative, yet it is evident that despite its high profile, it remains one of the many things going on within society. Once the film approaches its final act, the case becomes clear and the murderers closer. The hunt is spruced by the energy Dassin brings to the film’s gritty camerawork and sharp editing. There’s even a witty touch of society and media satire. As the case unspools, it paints the victim as both femme and fatale without explicitly depicting her as such.

7. The Night of the Hunter (1955)

On one hand, The Night of the Hunter features film noirs’ most unique Homme Fatale. Robert Mitchum stars as Harry Powell, a murderer in the guise of a preacher and a wolf in the guise of a shepherd. On the other hand, it also has film noir’s most interesting protagonist, a young boy named John Harper (Billy Chapin). The film opens with a parable warning children to preserve their innocence in the face of evil. It manages to be both an astute satire as well as a sweet fantasy where love triumphs over all.

So, while Harper is a lovely child, he is also far more mature for his age and forced to bear the scars and weight of his father’s sins. In return, Powell is depicted as a man of faith who is ruthlessly misogynistic and extremist in his actions. The two collide in a bid to see whether love can win out against evil, yet not in the most straightforward manner.

Fanaticism in religion and society is depicted as a great ill that ultimately suppresses the pure desire to retain the established patriarchal order. The subtext finds ways to comment on the suppression versus the empowerment of the feminine. In that sense, Rachel Cooper (Lillian Gish), who eventually protects John and his sister Pearl, becomes the antithesis of Powell. She is a woman who believes in the rewarding power of faith, which lets children be children without patronizing and shielding them from the reality of an adult world. The tone, in that case, is enchanting. The brazenly stark noir visuals reflect a strange and surreal world. Although aesthetically, the film feels like a film noir, it acts as a children’s fantasy with a musical touch.

8. The Set-Up (1949)

In one of his finest roles, Robert Ryan stars as Bill “Stoker” Thompson, an aging boxer and classic hard-luck noir protagonist. Wise’s film focuses on the seedy and degenerate business of the Boxing world. Stoker’s desperation to win his big match, unaware that his faithless manager has planned a fix for him to lose, provides the necessary thrill in the picture. This is enhanced by the narrative choice to edit and showcase the film in real-time, a unique touchstone for the era.

The cross-cutting is masterful, as the narrative gives space to Stoker’s rising and dying hopes and also zeroes in on his wife strolling in the city. She cannot come to terms with Stoker’s failures, fearing he will die trying in the boxing ring. That threat of the sport materializes further in how Wise and Art Cohn depict the crowd during the match. The crowd is showcased as ravenous wolves devouring the violence with zero moral complicity.

The film makes a potent statement on the audience’s fascination with violence that ultimately results in the destruction of the hero. Speaking of the boxing itself, the craft is undeniably sleek, with the significant boxing sequence pictured in harsh black and white. One can see the influence of the film on the boxing sub-genre, especially Martin Scorsese’s Raging Bull. Though Stoker is victorious, like with any film noir, happiness is fleeting in the dark underbelly of this world. The price of a singular passion and obsession is the loss of that very thing. Stoker is forced to confront this loss when he is injured beyond help. In that sense, his wife is afforded the final victory, as Stoker can no longer be a boxer. Having said that, her victory, too, remains hollow and filled with emotional pain, unlike what a femme fatale would feel.

Related to Great Film Noirs without Femme Fatales: 10 Noir Films That Are Under 90 Minutes

9. The Third Man (1949)

During the opening credits of The Third Man, the audience sees and hears the disruptive tune of a zither. It is an upbeat yet maddening score that will consistently haunt this fish-out-of-water tale. Holly Martins (Joseph Cotton) is the penniless author of cheap Westerns who arrives in post-war Vienna seeking his friend Harry Lime (Orson Welles). Unfortunately for Martins, Lime has just been declared dead after a car accident.

When the desperate Martins chooses to stick around and solve the odd case of Lime’s death, he is beset on all sides by different Military Police occupying their own space in Vienna, as well as the black-market criminals related to Lime. As the investigation unravels and Martins confronts the truth of Lime’s character, the craft of the film morphs daringly to depict his alienation. The zither score becomes irritating and indicative of shock moments, while the camera work employs Dutch angles with increasing frequency.

The madness and darkness of Vienna envelop Martins, all alone except for the aid of Lime’s lover, Anna Schmidt (Alida Valli). The visuals surrounding her are absurd; it is clear that she is a blinded innocent falling into the trap concocted by Lime’s action. Martins’s own selfish desires for her impede his pursuit of the truth, causing further turmoil for Anna. Things are further complicated with the twist reveal of Lime’s death being faked, Orson Welles delivering a magnetic turn in a short role. Cotton’s Martins, in turn, becomes an unwitting Cowboy for the girl. He plays the hero in a world gone mad and loses his sense of self for his sense of justice. The action-packed climax across the sewers of Vienna ratchets up all of this. The final shot is a masterful depiction of the tragic state Film Noirs close their stories with.

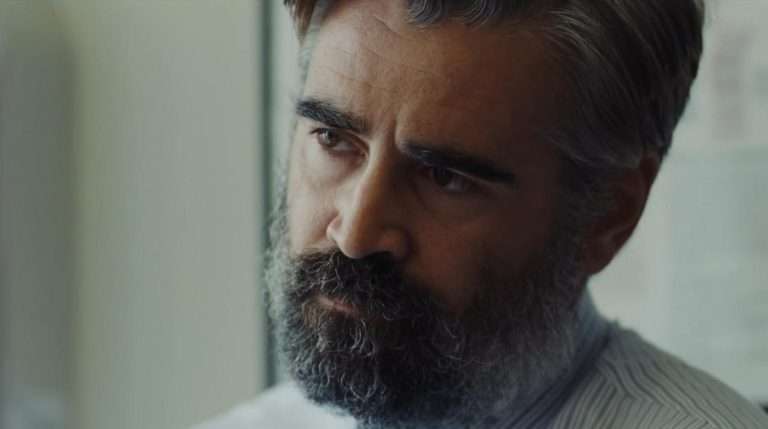

10. Touch of Evil (1958)

Few directors, especially of that time period, can measure up to the mastery of Orson Welles. He depicts the intent of his scenes with clinical precision; the opening of Touch of Evil is a perfect example. A three-minute-long crane shot opens the film as the viewer witnesses the planting of a bomb in a car. The camera snakes across the lively border town in Mexico, focusing on our protagonists and framing the car at the edges until it ultimately blows up. This piece of craft is impeccable and an untouchable iconic moment of Film Noir, an inciting incident for an exciting story.

Though controversially slathered in brown face makeup, Charlton Heston stars as Ramon Vargues, a prosecutor who gets involved in the ensuing case. Ramon’s involvement encroaches not only on his honeymoon with his wife Susan (Janet Leight) but also the border town Police force and lead investigator Hank Quinlan (Orson Welles). It’s a daring battle of wits between the two leading men. Ramon’s deep dive investigation reveals a complex conspiracy with Quinlan at the heart of it all.

As his actions further obstruct Quinlan’s plans, the editing beautifully cuts between Ramon and Susan’s journey around the town, putting her in grave danger. The violence implied is still disturbing, with Russell Metty’s shadowy cinematography distorting the perceptions of the strange world the couple is thrown into. Even though Leigh’s Susan is a spitfire, she is a woman playing in a man’s world. This propels Ramon’s pursuit of the truth and acts as the consequence of his actions. Welles’s genius as a filmmaker is matched by his own performance.

There’s his signature deep-focus filmmaking meshed with absurd low-angle shot-taking that enhances the towering threat of Quinlan. The writing also adds layers to his cruel villain, providing him a tarot card-reading lover, the closest the film comes to a femme fatale. Yet, much like Susan, she too is a victim of circumstance. Their roles essentially theorize that the feminine in film noir is often at the mercy of the actions of the masculine. They suffer in the tragedy whether directly involved or not.