In a country where cinema often spills into the realm of religion and movie stars are often treated as demigods, it’s not unusual for actors to acquire a devoted fan following. But even among the pantheon of larger-than-life figures, Rajinikanth stands singular. What is unusual is the way Rajinikanth became something beyond the boundaries of stardom – a living, breathing, evolving phenomenon whose very name elicits cheers, tears, fist-pumps, and milk abhishekams at the foot of giant cardboard cutouts.

To call him an icon is still insufficient. Rajinikanth is a cultural phenomenon, one whose legacy cannot be understood through mere box office numbers or awards, but through the pulse of a million fans who worship his screen presence with the zeal of religious devotion. To explain Rajinikanth to someone unfamiliar with Indian cinema is akin to explaining the force of a monsoon or the logic of folklore. You don’t analyze it; you absorb it. He is not merely a man on screen; he is an event, a feeling, a spectacle that renews itself with every entry scene.

Also Read: 14 Great Tamil Movies You Can Stream on Netflix Right Now

But how did a Marathi-speaking bus conductor from Bangalore named Shivaji Rao Gaekwad become Thalaivar, the undisputed leader of the Tamil masses, the most bankable star of Indian cinema, and eventually, a global icon? To answer that, we must travel through decades of cinematic evolution, mass psychology, myth-making, and the sheer magnetism of a man who never tried to be anyone but himself, yet ended up becoming everyone’s hero.

Style as Substance: The Birth of ‘Rajini Style’

Style is not an accessory in Rajinikanth’s cinematic world, it is the language of his existence. It isn’t just in his clothes or looks, it’s in his gestures, his pauses, his paean-worthy walk. When he flicks a cigarette into the air and catches it between his lips, or when his sunglasses arc gracefully before landing on his face in perfect symmetry, the action isn’t about spectacle, it’s a ritual, an announcement: Rajini has arrived. Take the mythic cigarette flip from films like “Billa” (1980) or the sunglasses toss immortalised in “Annamalai” (1992) or the stylish coin toss in “Sivaji: The Boss” (2007). These flourishes became more than gimmicks, they were signature moves, recognisable from silhouette alone.

Early films like “Billa” (1980), a Tamil remake of Amitabh Bachchan’s “Don” (1978), first introduced this heightened performativity. But it was with “Murattu Kaalai” (1980), “Thee” (1981), and “Moondru Mugam” (1982) that a distinctive pattern emerged. Rajinikanth’s characters combined street-smart resilience with a magician’s flourish, a rogue’s charm, and an unmistakable moral compass.

His style worked not because it was polished, but because it winked at the audience. There was always a sense of self-aware bravado, of someone in complete command of his image but never taking himself too seriously. That delicate balance is nearly impossible to achieve, and yet, Rajinikanth made it look effortless. Audiences didn’t just watch these moments, they memorised them, mimicked them, and transformed them into public rituals.

You could hear the echoes of Rajinikanth’s finger-flick, swaggering walk, or hair sweep in schoolyards, tea stalls, and street corners across Tamil Nadu. And it wasn’t just about the movements. It was about the confidence behind them. When Rajinikanth made a move, it wasn’t for the camera, it was for you, the viewer, in a kind of one-on-one communion that few actors have ever mastered.

Charisma Incarnate: Not Acting, But Commanding

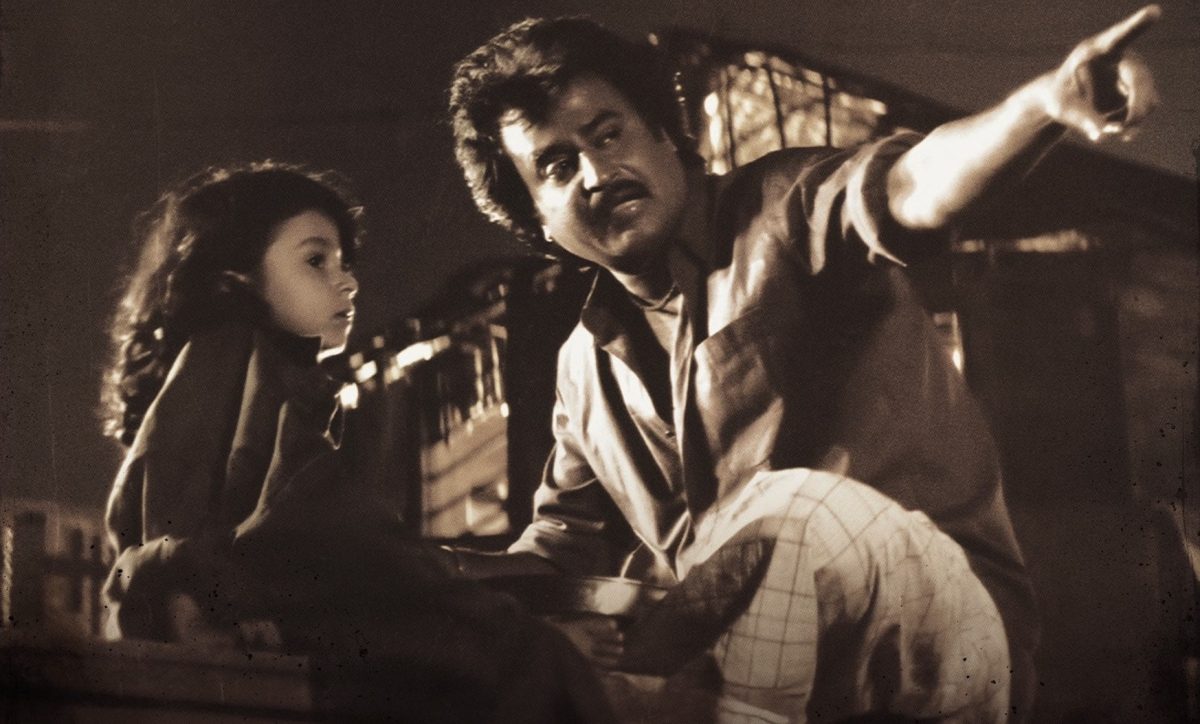

Rajinikanth is not the most “trained” actor in the conventional sense, nor the most versatile in the classical mould. But his charisma eclipses all else. Watching him on screen feels less like observing a character and more like being invited into his orbit. Consider “Baashha” (1995), one of his most iconic films. As the soft-spoken auto-rickshaw driver Manickam, Rajinikanth restrains his natural flamboyance, until the moment he reclaims his identity as a feared gangster. That transformation is one of the most electrifying in Indian cinema.

The moment he delivers the line, “Naan oru thadava sonna, nooru thadava sonna madhiri” (“If I say something once, it’s like saying it a hundred times”), audiences were sent into hysteria. The words themselves aren’t what caused it, it was how he said them: the rhythm, the pause, the measured threat wrapped in charm. Rajinikanth doesn’t just deliver lines, he alchemises them. And therein lies his mystique. He has a performer’s instincts, a theatre actor’s command over silence and volume, and a crowd-puller’s sense of timing. He is both poet and punchline, messiah and mischief-maker.

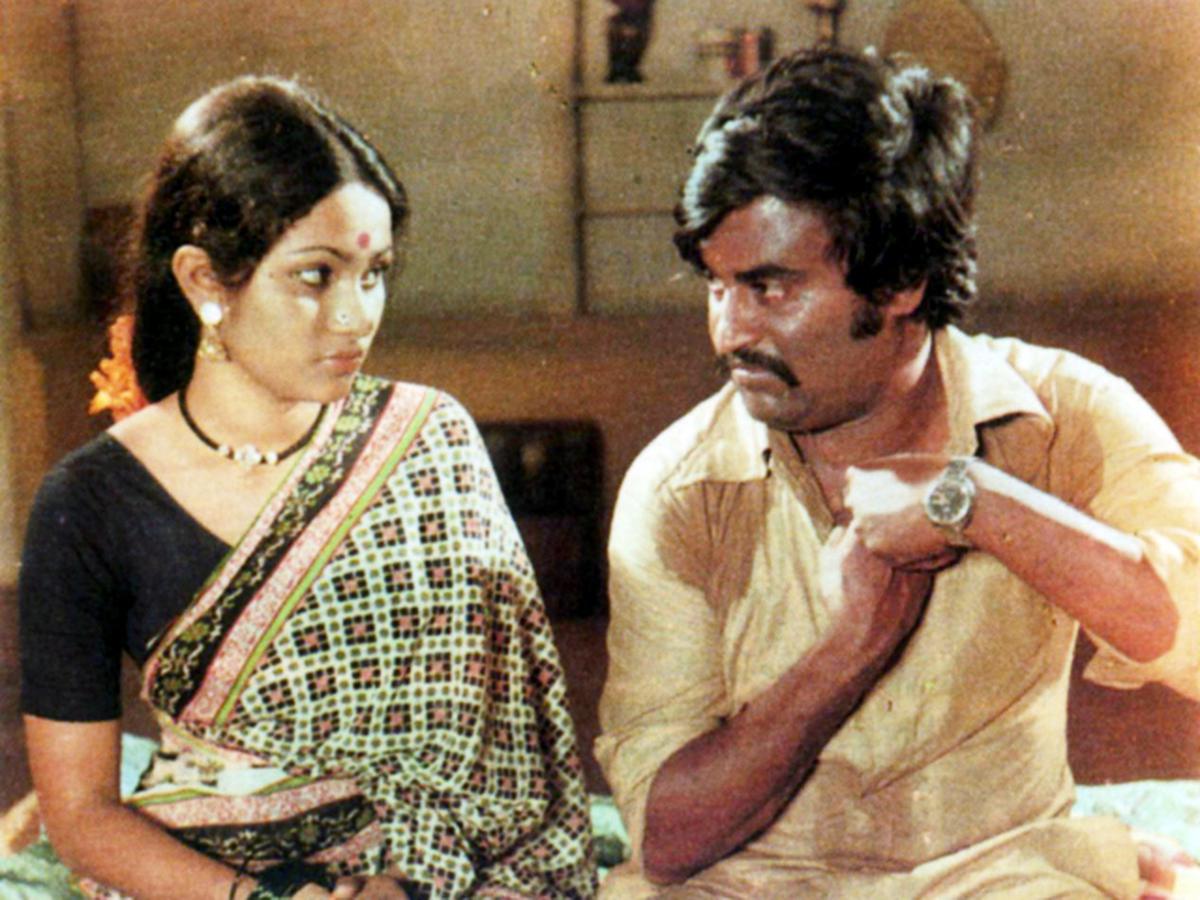

There’s a story that during the shooting of “Mullum Malarum” (1978), director Mahendran asked Rajinikanth to act without make-up, to just be. The result was spellbinding. As Kaali, the rugged winch operator with a moral compass skewed by emotion and injustice, Rajinikanth delivered one of his most raw, layered performances. No theatrics, no swagger, just presence. That’s the paradox of Rajinikanth: even when he dials down the drama, he commands the frame.

This charisma – raw, rooted, and radiant – translates into every genre he touches. Whether it’s the suave antihero of “Baashha” (1995), or the wise, larger-than-life robot in “Enthiran” (2010), he doesn’t just play characters, he inhabits them. Watch him in “Padayappa” (1999), where a simple movement, a lifting of sunglasses with the flick of a finger, elicits deafening cheers in theatres. Or his powerhouse scene in “Sivaji: The Boss” (2007), where he transforms from a cornered NRI into a vigilante Robin Hood, delivered with trademark dialogue delivery: punchy, playful, and precise. It’s a theatre within the theatre.

The Manners that Became Mannerisms

Rajinikanth’s superstardom doesn’t rest solely on his roles, dialogue delivery, or storyline choices. It resides equally, if not more profoundly, in the lexicon of mannerisms he has cultivated over decades. These aren’t just stylised movements; they are ritualistic gestures, non-verbal symbols loaded with cinematic, cultural, and emotional significance. Rajinikanth didn’t just act, he authored a unique body language that audiences learned to read like scripture. These mannerisms, often improvised or organically developed, became a grammar of charisma.

Take the flick of the hair. What began as a regular style choice in his youth became, over time, a kind of performance in itself. The flick, the comb-back, the shake – all performed with a rhythm that made them stand-ins for rebellion, cool, and defiance.

In “Sivaji: The Boss” (2007), director Shankar turned this mythos into high-octane self-awareness. The film pokes fun at Rajini’s style while simultaneously celebrating it. The fairness cream gag, the counting coins scene, the climactic comeback with silver hair and dark glasses, all of it is constructed with meta-cinematic flair, and Rajinikanth leans into it with both irony and bravado. In a society where physical gestures often imply hierarchy, his head-flicks and finger-snaps weren’t just affectations, they became shortcuts to attitude, gestures that could stand in for a whole scene of dialogue.

His gestures, be it the rapid finger spin before making a point, or the dynamic head-tilt in a face-off, have become non-verbal signatures, as recognisable as any logo. Even his gait carries narrative weight. In “Padayappa” (1999), when he climbs the steps of his ancestral home after years of exile, every footfall seems to echo history and redemption.

That scene is choreographed not with background dancers or special effects, but with posture and gaze. In “Muthu” (1995), he uses the finer roll while delivering punchlines with flair, giving the impression of someone playfully in control, toying with time and fate. The audience doesn’t need translation, the movement speaks Rajinikanthese.

Also Read: How the Depiction of Trauma Humanizes One Killer and Villainizes the Other in ‘Por Thozhil’?

Another iconic move: the coin flip. In “Sivaji: The Boss” (2007), he doesn’t merely flip a coin; he manipulates it mid-air, catching it in unexpected ways while still maintaining eye contact with the villain. This gesture, both technically demanding and theatrically precise, becomes a metaphor for fate, as if Rajinikanth is showing us he can bend luck itself to his will.

Let’s not forget the sunglass toss, perhaps the most famous of all. Whether it’s the horizontal swing and catch in “Baashha” or the circular airborne loop in “Sivaji: The Boss,” these moves are so popular that they have become memes, ringtone sounds, GIFs, and even ritual acts by fans in marriage halls and public functions. What’s remarkable is how he repeats these stylisations across films without ever making them feel stale. Each time, the sunglasses’ move is recontextualised, sometimes comic, sometimes defiant, sometimes prophetic.

Even his walk is different. It has an almost architectural rhythm: feet placed with authority, shoulders squared, chin raised, not too high to be arrogant, but just enough to suggest unbothered supremacy. It’s the walk of someone who doesn’t just own the scene, but owns the air within it.

But what truly elevates these mannerisms from habit to metaphor is how they communicate emotion without explanation. They have become his shorthand for complex states of being: confidence, rebellion, righteousness, mischief, defiance. In films like “Padayappa,” his calmly defiant body language becomes a counterpoint to the theatrical villainy of Ramya Krishnan’s Neelambari. He doesn’t react with aggression—he responds with gestural economy, as if to say: “I don’t need to raise my voice; my posture speaks volumes.”

This mastery of movement places Rajinikanth in the lineage of physical performers like Charlie Chaplin or Buster Keaton, artists who understood that a well-timed gesture can carry more power than a page of dialogue. Rajini’s movements are exaggerated, yes, but not clownish. They are stylised, but not disembodied. They are grounded in emotional realism even when they defy physics.

Importantly, these gestures were never designed to appeal to critics or cinephiles. They were always meant for the mass audience, the bus conductor, the fish vendor, the child in the front row of a single-screen theatre. And that’s perhaps their greatest strength: they are inclusive, mimicable, and malleable, passed down like folklore through generations of fans. And so, over time, what began as performative flourishes has become cultural artefacts. They exist not just within films but beyond them, in WhatsApp stickers, TikTok videos, political rallies, advertising campaigns, college debates, and public processions. These mannerisms have leapt off the screen into the real world, becoming part of how we express ourselves.

A Mirror to the Masses

Rajinikanth’s superstardom isn’t predicated on unattainable beauty or elitist sophistication. On the contrary, his rise was precisely because he embodied the aspirations of the working class. He doesn’t merely act for the masses; he reflects them. Many of his characters are underdogs: rickshaw drivers, orphans, fishermen, labourers – men who wear their dignity like armour.

They battle corruption, injustice, and humiliation with wits, style, and unshakable self-respect. In doing so, Rajinikanth became the vessel through which the common man saw himself fight back. He rarely played zamindars or corporate tycoons. He played a rickshaw driver in “Baashha” (1995), a daily wage labourer in “Uzhaippali” (1993), a taxi driver in “Padikkadavan” (1985), and a factory worker in “Mullum Malarum” (1978).

These roles weren’t chosen to be humble; they were strategic and political. They aligned him with a vast underclass of viewers who saw their dignity, rage, and hope reflected in Rajinikanth’s screen journey. It helped, too, that he never allowed stardom to erode his off-screen humility. He frequently appears in public with minimal grooming, wearing a simple kurta or dhoti, speaking in unpolished, everyday Tamil.

He’s been known to bow before elders, temples, and even fans. In an industry obsessed with self-promotion, Rajinikanth’s self-effacement became radical. This contradiction, a man whose every on-screen gesture is exaggerated, yet who remains understated in real life, creates a magnetic duality. Rajinikanth, the man, earns reverence; Rajinikanth, the actor, earns mania.

The Sacred Ritual of Rajini Fandom

The release of a Rajinikanth film is not a cinematic event. It is cultural combustion. Fans queue up as early as 4 a.m., chant slogans, dance outside theatres, and bathe his posters in milk. Tickets are sold out weeks in advance. New releases feel like national holidays in Tamil Nadu, with drumming processions and confetti storms, especially in smaller towns where local businesses literally close shop on Rajini release day. He has become a part of the emotional and cultural grammar of South India. And yet, his influence isn’t limited to the South. He enjoys pan-Indian and global appeal, with fan clubs from Tokyo to Nigeria.

Fan clubs, numbering in the thousands, are more than social groups. They are organised, mobilised, and often politically active. His fans have built temples in his name. They conduct blood drives, clean-ups, and charity events under his banner. There is no scriptural parallel to this in any other film industry in the world. Rajinikanth’s screen entrances are accompanied by explosions of sound. The mere silhouette of his profile triggers a roar. In “Jailer” (2023), as an ageing jail warden with a dormant past, he walks into frame with a gravitas that turns nostalgia into thrill, proving yet again that age may weather the body, but never the aura.

Related Read: Jailer (2023) Movie Review

And what explains his reach across language and region? Perhaps it is this: Rajinikanth’s stardom is not tethered to realism or even relatability. It is based on a contract with wonder. We go to his films not for plausibility, but for possibility, the possibility that a man from the crowd can rise, speak truth to power, and still crack a joke while doing it.

Legacy: Stardust in the Bones of Indian Cinema

To speak of Rajinikanth’s legacy is to attempt to sketch a constellation with a single stroke. His impact is not confined to the Tamil film industry, or even to Indian cinema at large. His influence seeps into language, politics, fashion, mimicry, meme culture, moral imagination, and regional pride. It’s not merely a career, it’s a cultural inheritance, passed down like a myth that still breathes.

For over five decades, Rajinikanth has remained uncannily relevant, even as the cinematic landscape has transformed around him. He has traversed eras, from celluloid to digital, from VHS to streaming, and yet retained his core audience while gaining new ones. In an industry where fame is fleeting and newer stars are constantly manufactured, Rajinikanth has not just survived, he has expanded.

Younger actors and filmmakers across India, from Dhanush and Vijay Sethupathi to Yash and Allu Arjun, often cite him as both influence and inspiration. Bollywood megastars like Shah Rukh Khan have openly paid homage to his aura, with SRK even mimicking Rajini’s style in “Chennai Express” (2013). Directors like Shankar and Karthik Subbaraj have built entire visual universes around the mystique of “Rajini.” Yet no one has been able to replicate the alchemy that is uniquely his.

Rajinikanth has also shown the courage to evolve with age, a rare trait in an industry addicted to youth. He’s not afraid to appear vulnerable, greying, or introspective onscreen. Films like “Kaala” (2018), “Kabali” (2016), and “Jailer” (2023) don’t hide his years; they honour them. In these roles, he plays a different kind of hero, not the invincible avenger, but the seasoned patriarch, the weary fighter, the wise rebel. And yet, even these avatars carry the same pulse that thrilled audiences in “Moondru Mugam” (1982) or “Thalapathi” (1991); a pulse that says: “I may be older, but I’m still the moment.”

His influence also transcends screen space. Rajinikanth’s name has been invoked in political campaigns, street protests, memes, prayers, jokes, and even scholarly essays. When he briefly dipped into politics, crowds surged not because of ideology, but because of the trust he had built over the years as a symbol of incorruptible strength. Even in retreat, he remains powerful, a reminder that his currency is not just cinematic but emotional, social, and cultural.

What sets Rajinikanth apart is not just his star power, but the intimacy of his superstardom. He doesn’t stand on a pedestal above the masses, he walks among them. He is the actor of the people and the dream of the ordinary. His rise from the working class to international fame is not just aspirational; it is affirmational. He is proof that you can speak simply, dress plainly, live humbly, and still possess an aura that bends reality.

The Enduring Flame

In “Jailer” (2023), a more weathered, sombre Rajinikanth still ignited theatres with that familiar fire, proving that even at 70+, his mere presence is enough to pack halls and provoke whistles. Not because he reinvented himself, but because he remained unmistakably Rajini, a master of mass appeal with effortless magnetism. And now, anticipation is at a fever pitch as he prepares to return to the screen in Lokesh Kanagaraj’s “Coolie.” If “Jailer” was a reminder of his enduring power, “Coolie” promises to set the screen ablaze once more.

Rajinikanth is more than an actor, he is an unstoppable cultural force. A singular blend of style, humility, swagger, and an intuitive understanding of cinema, he has transcended the boundaries of stardom to become a site of pilgrimage, a cultural memory, and a generational bridge. Over nearly five decades, he has remained not just relevant, but revered. As cinema has evolved, so has Rajinikanth, allowing his image to age, his body to slow, and his roles to deepen. Yet, he has always retained the essential spark that first captivated millions: a magnetic fusion of humour, heat, and humanity. In the dictionary of Indian cinema, if ‘Superstar’ had a picture next to it, it would be Rajinikanth’s. Not smiling. Just walking. Sunglasses spinning in his hand.

His charisma is not timeless because he defied time, but because he danced with it, embracing change without losing identity. In the cosmic script of Indian cinema, Amitabh Bachchan may be the patriarch, Kamal Haasan the chameleon, but Rajinikanth is the supernova, a star whose light burst forth long ago, yet continues to illuminate across generations. Even now, when he steps into a frame, spinning sunglasses or simply standing still, time pauses, gravity waits, and cinema bows.