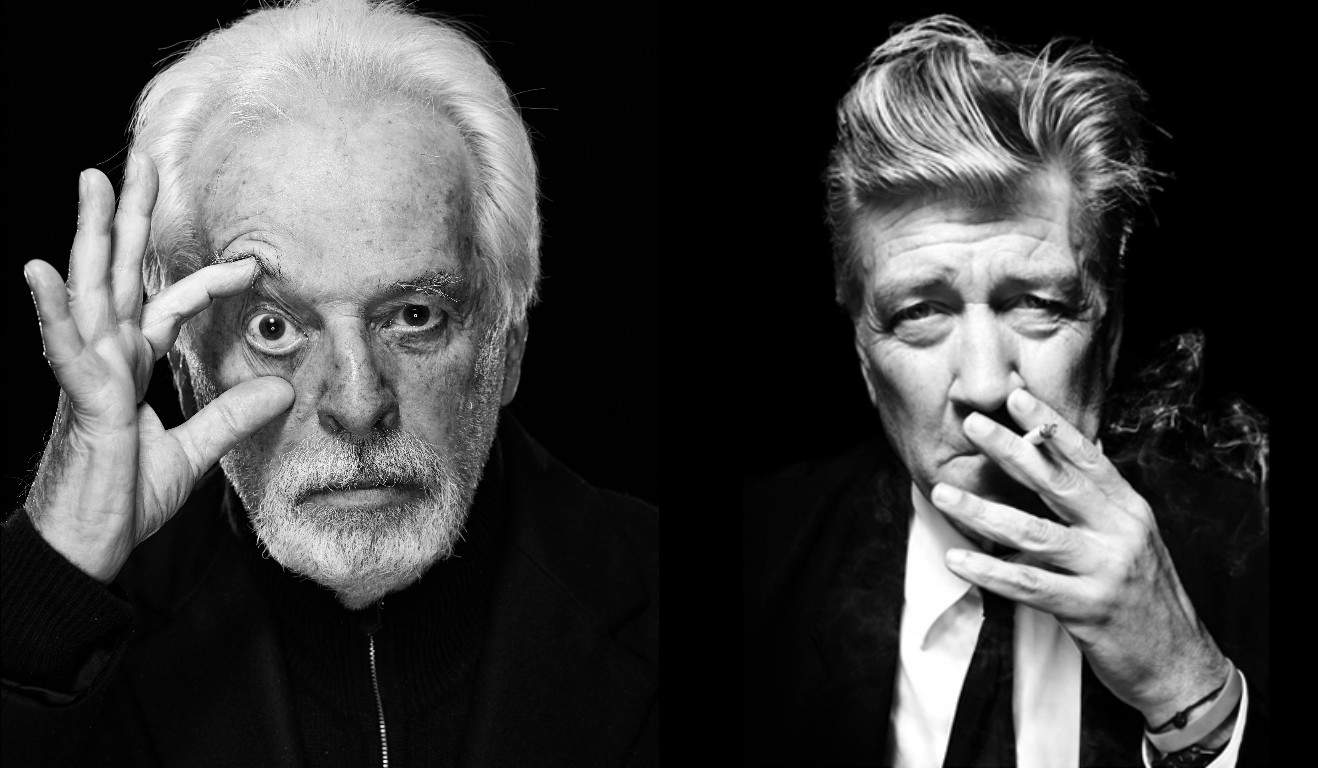

David Lynch Film Guide: To many cinephiles, David Lynch is the peak of pop surrealism, an artist whose mind-bending puzzle boxes flirt with the avant-garde whilst embracing the history of American genre cinema. Despite his unorthodox style, he has an almost unparalleled cult following of fans who worship his estimable filmography and work on Twin Peaks, perhaps the most singular artistic statement ever committed to network television. They spend years looking for answers in his worlds of perplexing dream logic, populated by memorable, quirky characters that are offset by moments of genuine terror.

The perplexing nature of his work almost makes it universal, as no matter what level of experience you have with his work, you’ll probably be equally confused, left with the effective visceral experience evoked by Lynch’s collision of subverted Americana with alien dreamscapes. He’s almost definitely the most daring filmmaker to have racked up multiple Academy Award nominations and work with Michael Jackson.

Particularly since the turn of the millennium, Lynch’s work has taken on a mythic, transcendent quality, all the more appealing to his diehard fans. He’s one of the few directors who has envisioned a genuinely enthralling future for digital cinema after decades of perfecting his unique style on celluloid. He’s also become an increasingly visible public figure via charming weather reports on his YouTube page and even an outstanding performance as John Ford in Steven Spielberg’s The Fabelmans. That’s without mentioning his digressions into visual art and music: he’s practically the godfather of the dream pop movement associated with frequent collaborator Julee Cruise. But this article will just focus on his work in film and television, where he has defined and redefined the public’s idea of what mainstream American cinema can achieve. Don’t ignore what even your most annoying cinephile friends have told you – David Lynch is worth the hype.

Where To Start With David Lynch

Blue Velvet begins with a scene of the American idyll – white picket fences et al. – before panning down to show bugs burrowing into a toxic surface beneath. It’s hardly the most subtle introduction to the world of Lynch, but a suitable primer nonetheless. It feels like a filmmaker hitting his stride and making his first, most trenchant insights into the themes of anthropology, American institutions, and sexual violence, which would color virtually all his subsequent work. Before then, there had been the lysergic debut Eraserhead (shot on a micro-budget and informed by Lynch’s own fear of fatherhood), then director-for-hire job The Elephant Man (effective, if a little blunt), and the notoriously disastrous Dune adaptation in 1984.

Blue Velvet marks Lynch’s second collaboration with leading man Kyle MacLachlan, the charming force for good who must oppose the evil within his universes, and first with Angelo Badalamenti, the late, great composer whose eerie soundscapes make Lynch’s work instantly recognizable. The film’s portrayal of female suffering, through the brave performance of Isabella Rossellini, garnered controversy, as did Dennis Hopper’s infamously abrasive turn as the evil ringleader of this small town’s nefarious wrongdoings. Watched today, it doesn’t pop as many monocles, but its authentic presentation of the terror wrought on women by their male oppressors remains harrowing and surprisingly progressive. It may be influenced by the visuals of dreams, but Blue Velvet is planted in a sort of reality, which makes it the ideal starting point for Lynch, showing the human heart behind the horror.

Delving in…

Now you’ve familiarised yourself with Lynch, it’s time to spend countless hours in his other hellish depiction of small-town America: Twin Peaks. The impact of the show’s first season is hard to comprehend now when prestige “cinematic” TV shows are a dime a dozen, but this blend of murder-mystery, soap opera pastiche, and outright surrealist nightmare fuel caught a nation off-guard and had everyone from middle America to the White House (George H.W. Bush and his Soviet counterpart Mikhail Gorbachev were allegedly both fans) asking “who killed Laura Palmer?”.

Lynch and co-creator Mark Frost never wanted to tell you, but their bosses forced their hands. To plant myself firmly on the wrong side of history, I’m glad that the killer was eventually revealed, mainly because that climactic episode is among the most thrilling in television history. The much-maligned Season 2 – following Lynch’s departure – is far more muddled and kitschy and only rediscovers its groove with the introduction of new villain Windom Earle.

The prequel film Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me premiered to tepid reviews at Cannes in 1992 but has now been reappraised as the masterpiece it is. The tone is noticeably harsher than the show, though it, of course, is a depiction of the same series of events. Its portrayal of sexual violence and misogyny burns with empathy, which is still, unfortunately, too rare among contemporary horror films addressing similar themes. The script never spills over into exploitation, instead letting Sheryl Lee’s petrifying screams of terror become the human embodiment of feminine terror.

The darker tone certainly set a precedent for Twin Peaks: The Return, which, even by Lynch’s standards, is hard to comprehend on first viewing. It essentially carries over the original series’s fundamental plight of good vs. evil. However, given extensive creative freedom by Showtime, Frost and Lynch can expand this story to encompass new realms of visual invention and moral complexity. The entire Twin Peaks franchise is a testament to his ability as a world builder, director of actors, and storyteller.

For the diehards

Inland Empire is the most recent – possibly last – feature film Lynch has directed, all the way back in 2006. Plot details border on the superfluous for a movie whose appeal lies in the ways that the filmmaker is expanding and contracting the medium. Boiled down to its simplest essence, it is a film about “a woman in trouble,” another interrogation into the feminine psyche, and a film that, like Mulholland Drive before it, is informed by Hollywood culture and history. It’s very much a product of its time, a valuable relic of the 2000s when directors like Lynch, Michael Mann, and the Wachowskis (Lana & Lilly) were exploring the capabilities of digital photography.

The visuals of Inland Empire are not the immediately pleasurable sights seen in the likes of Blue Velvet, but they represent an inspiring sort of artistic liberation through their disregard for conventional film grammar. The narrative convention is similarly askew, snapping into occasional moments of clarity before pulling you back out again. There’s nothing quite like it, and it divides even the hardcore following of Lynch. For some, it’s an act of admirable but ultimately joyless indulgence; for others, it’s his magnum opus. Watch it for yourself and find out which side of the debate you align with.

Best of the rest

Mulholland Drive is the most obvious omission from the list thus far. It’s a classic Hollywood mind-bender, frequently ranked as Lynch’s masterpiece and among the best films of all time (number eight on Sight & Sound’s most recent poll). It tells the story of Naomi Watts’ Betty and Laura Harrings’ Rita across multiple dimensions, the dream world and the real, in a plot that unfurls in that magical Lynch way, “like a string of pearls,” to quote the man himself. It is the most erotic Lynch film by some distance and contains some of the most memorable images of his career. A seasoned Lynch lover may parrot the virtues of his other masterpieces, but there’s no denying the qualities that made this such a sensation at the time.

Lost Highway is a personal favorite of mine, gripping from its opening scenes of a jazz player on the edge as he expresses every fiber of his insecurity in his art. Music is very much the tenet of this picture, both Badalamenti’s score and the soundtrack, including songs from Smashing Pumpkins and Lou Reed. The plot is another take on the duality of man through two seemingly unconnected stories which intertwine. Even a filmmaker as daring and original as Lynch isn’t averse to doing variations on a theme, but who are we to complain when the work remains so good?

For those scratching beneath the surface, there are a plethora of short films directed by Lynch in the 2000s, the best of which is Rabbits, 50 minutes of a bizarro-world sitcom acted out by puppets. Once you get past the immediate novelty of it, it’s actually layered and involving in a way that most directors’ non-feature pet projects aren’t. Another worthwhile curio is the abandoned TV show Hotel Room, which traverses time and space through the prism of a New York hotel. The three existing episodes are only available on VHS quality copies today, but the potential is clearly there, elevated by a cast including the great Harry Dean Stanton.

The only features I haven’t yet mentioned are Wild at Heart and The Straight Story, which bookended the filmmaker’s most fruitful decade, the 1990s. The former was a Palme d’Or winner and is contagiously frenetic and horny, featuring winning performances from Nicolas Cage as well as real-life mother and daughter team Diane Ladd and Laura Dern. The Straight Story was made for Disney (no, really) and is – depending on who you ask – a ponderously slow or transcendently beautiful take on the road movie. Neither ranks among my absolute favorites, but both have moments of value and speak to Lynch’s underestimated range as a director.

Ultimately, when delving into such an acclaimed filmography, it is essential to find your own favorites, the themes you can connect with, and the performances you latch onto. Despite the cerebral nature of his dream worlds, Lynch is an intensely personal filmmaker for me and many others. If you’re only just getting started, then you’re in for one hell of a ride.

![The Wolf House [2018]: The Most Inventive & Imaginative Animation of the 21st Century](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/the-_wolf_house-768x416.jpg)

![Lake Michigan Monster [2020] Review : Grab a tub of popcorn and let this movie lead you to a madcap journey](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Lake-Michigan-Monster-768x432.jpg)