Ken Russell was quite simply one of the maddest filmmakers ever. The performances under his direction were impassioned, his technical craft was uniquely demented, and the ideas he placed in his films were truly singular. His presence in world cinema, and even more so in British cinema, is completely unparalleled as his films went deep into the psyche and emotional turmoil of the fascinated, the curious, and the ambitious.

Has there been any other director who has so wildly portrayed so many artists with such a burning intensity? Savage Messiah is one of the several artist bio-pics from British filmmaker Ken Russell and it seems to be the one that most matches the artistic frenzy that this director himself possessed.

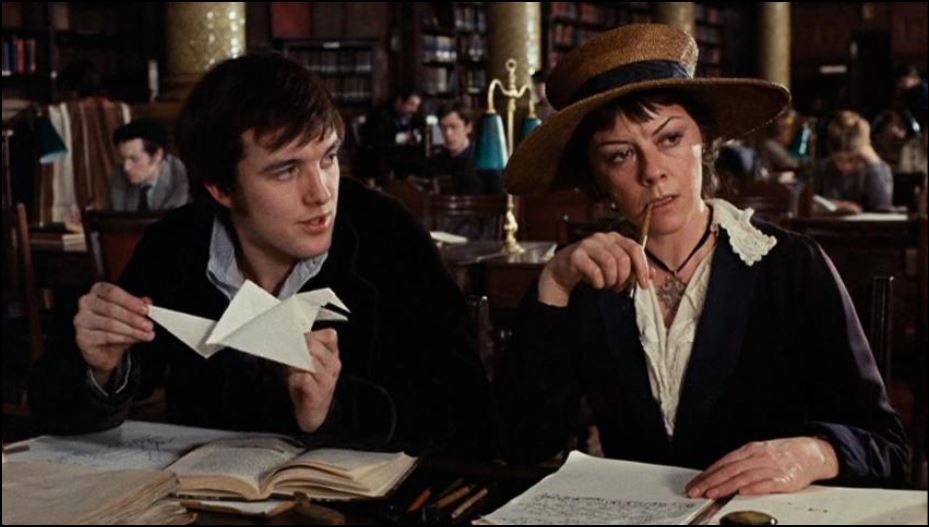

Henri Gaudier has the talent and temperament of an artist: he’s intensely impulsive, maddeningly uninhibited, and dedicatedly ambitious. He’s also extremely opinionated and most often very vocal, with no filter when praising or (more likely) harshly criticising the actions or appearances of others. This makes his relationship with Sophie Brzeska a mostly fraught one: as soon as he meets her, he proclaims his love for her (despite her being twenty years his senior), and since his raw openness makes her too feel she can express her tortured condition freely when with him.

Right from the film’s beginning, it appears to be more an exploration of this disjointed relationship with an artist rather than the artist himself. The age difference between Henri, in his late teens and early twenties, and Sophie (in her later thirties) shows his wild optimism clashing (or collaborating) with her given up and is spiritually rotting.

They act like a married couple, but don’t have all the qualities. They’re not legitimately married, and Sophie doesn’t even have sex with him, leaving him and his young sexual instincts to go find alleviation for his lust from prostitutes and mistresses. Sophie encourages this, until a heart-breaking moment when he brings a mistress Gosh (Helen Mirren) home, who’s the kind of special woman that highlights the flaws and short-comings that Sophie possesses.

Ken Russell aims his sights foremostly on this relationship before Henri’s art, but the depictions of both are powerful, especially how they influence each other. Henri is primarily a painter, but he admits to an art dealer he can provide works of sculptures to him – by morning-time, so he immediately gets to work. Henri apparently loves working under pressure, or it’s maybe the only way he can work, as this pressure results in art that has an edgier quality than the romanticised portraits he’s seen earlier producing in a class.

Henri’s repetitive chipping of the sculpture becomes a part of the editing, cutting between shots at every bang, some shots lasting a second or less. Henri loudly vocalises his personal and political objections as he crafts his sculptures throughout the night, likely not bothering anyone, as he lives right beside a noisy train-line.

With such a passion for his art-work and more so for his closest companion, Ken Russell’s adaptation of the 1931 Henri Gaudier biography by H.S. Ede took this first-documented account of Henri’s partner and elaborated on it even further, to the point of making it the focal aspect of the film, showing how his love, lust, and romantic frustration affected his art, rather than the other way round.

![Manchester By The Sea [2016] – JIO MAMI Mumbai Film Festival Review](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Manchester2.jpg)

![Kin-dza-dza! [1986] Review – An Extremely Amusing Soviet Sci-Fi Cult Classic](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/kin-dza-dza-1986-1-768x576.jpg)

![Lookback on Lumet: The Offence [1973]](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/vlcsnap-error063-768x459.jpg)

![In My Father’s Den [2004] – A Haunted Loner’s Journey through Time and Memory](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/In-My-Fathers-Den-1-768x431.jpg)

![Unplugging [2022] Review: A Relatable Comedy about Digital Detox that Shines Through All Odds](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Unplugging-Movie-Review-1-768x311.png)