Padatik (The Guerilla Fighter aka The Foot Soldier, 1973) is the final part in Mrinal Sen’s ‘Calcutta Trilogy’: movies that captured the tempestuous sociopolitical conflicts in a rapidly changing urban space. Though Mrinal Sen made his debut feature, Raat Bhore in 1955, it was Bhuvan Shome (1969) – one of the first films to be bankrolled by Film Finance Corporation (now NFDC) and gave rise to the parallel cinema movement in India – that established Mr. Sen as an important film-maker. Later, Calcutta Trilogy became the most defining work in his oeuvre where his visual treats and thematic depths came together. The confluence of Mrinal Sen’s intimate self-examination of the Bengali underclass characters with the broader sociopolitical turmoil in Interview (1970), Calcutta 71 (1972), and Padatik (1973) set the standards for his incisive yet sensitive outlook at India’s social fabric.

Revered as well as criticized for his markedly Marxist ideals, Mrinal Sen was unlike the liberals attempting to impose a parochial vision of revolution and social change. As he mentions in his memoir: “Watching the bewildering reality of the instant present, I learned and unlearnt a huge lot” [1]. In fact, Padatik offers a critical look at the left-led protest movements in West Bengal in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Mr. Sen channels his ‘critique from the inside’ through his radicalized young protagonist, Sumit (Dhritiman Chatterjee). Infusing Godardian aesthetics and documentary footage, the film-maker’s exploration of a comrade’s frustration and discomfort is in fact as relevant as ever.

Related to Padatik: The Enduring Relevance of Mrinal Sen

Padatik opens with a disorienting, handheld camera shot of a young man desperately running along the dilapidated lanes. Sounds of firing follow him. It’s cut to a freeze-framed close-up shot of the young man, hinting that he is riddled with bullets. The frozen frame is burnt and then pops up the title. Political violence rocked Kolkata in the early 1970s as hundreds of youths suspected of CPI (ML) – Communist Party of India Marxist-Leninist – leanings were brutally murdered. In late June 1971, West Bengal was placed under President’s rule. Dubbed as the counterrevolutionary tactic, the police, and hired hoodlums went on a rampage, burning, chopping, and gunning down the individuals alleged as Naxalite, CPI (ML) sympathizers, and even some of their family members [2]. The narrative of Padatik is set in this backdrop of the siege within Kolkata as youths with revolutionary dreams got crushed by the establishment.

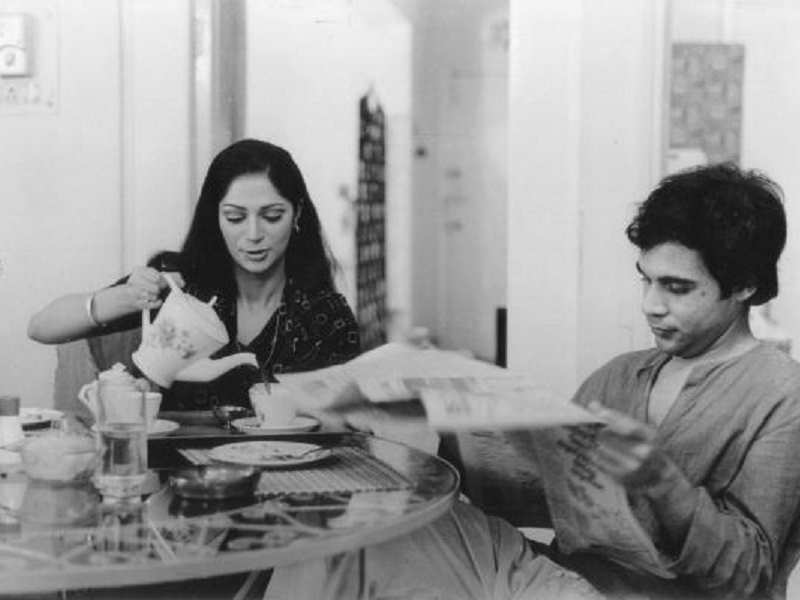

The city was also undergoing a tough time in terms of unemployment and poverty. And Sen often juxtaposes Sumit’s plight with newspaper headlines, highlighting the despondency and penury not only plaguing Kolkata but the entire nation. Having escaped from the police custody, Sumit is arranged by his Party superior to hide in the apartment of an upper-middle-class divorcee, Mrs. Mitra (Simi Garewal). Accompanied by his friend and tactless comrade Bimal, the neatly dressed and well-shaved Sumit is parceled to the 8th-floor apartment (“You’ll make me a Park Streeter”, protests Sumit). Burdened by isolation and uncertainty, Sumit begins re-examining his life, his affiliation with the Party, and the city’s aggravating crisis.

Calling the high-rise apartment a ‘decorated hell’, Sumit recollects his conflict with his father (Bijon Bhattacharya), once a revolutionary fighter but now an exploited worker. Moreover, he feels guilt over leaving his younger brother and bed-ridden mother. After a few days of spending alone in the apartment, Sumit meets Mrs. Mitra who works for an advertising firm and is back from her Delhi trip. The social, cultural, and economic gap between Sumit and Mrs. Mitra makes us wonder what exactly turned her into a Party sympathizer. Though the answer emerges organically later in the narrative, they both keep to themselves, exchanging pleasantries and having a cup of tea together.

Padatik does have a beginning, middle, and an end, but mostly driven by Mrinal da’s distinct aural-visual approaches. The plot and the set-up are minimal. The script was written by the film-maker and his friend Ashish Burman effectively intersperses the internal struggles of the two central characters with the broader struggles of the global society. Of course, as I mentioned, it’s not the issues spoken here but the way it was handled stylistically that allows viewers to immerse themselves in Padatik’s complex milieu. The newspaper headlines appearing on screen – ‘Crisis surfaces in Tamil Nadu’, ‘Gujarat several plants are closed’ – foregrounds the general sociopolitical and socioeconomic unrest (of the era) wrecking the nation. Such announcements external to the narrative reminded me of the agitprop motifs employed in ‘Third Cinema’.

Few scenes are violently cut to incorporate the footage of North Vietnamese soldiers, Japanese student protests, and militant activities in Latin America and Africa as Mrinal da emphasizes his solidarity with peoples struggling across the world. This seems to attune to the Party rhetoric (or Marxist truisms), contesting how all the political turmoil rises out of global concerns, and further extrapolating that addressing the concerns would realize the revolutionary dreams. Nevertheless, although Mr. Sen acknowledges all the comrades battling against the capitalist status quo, he comes across as a pragmatist questioning the absolute idealism and Party’s status quo when it doesn’t serve the dispossessed. The solidarity theme becomes clearer when Mrs. Mitra confesses her personal loss which led her to boldly shelter Sumit. But Mr. Sen in Padatik also populates her idealism with irony and contrast, one which we the middle-class people can easily relate with.

Also, Read: Loves of a Blonde [1965] – When Political Practices Invades Youthful Romantic Impulses

In one riveting sequence, where Mitra screens the ad-film she made for an infant supplement powders company to the company executives, Sen cuts to pictures of extremely malnourished Indian children while the enraptured catchphrases of the ad brings more bleakness. It feels as if the malnourished children are on the back of Mitra’s mind as she is catering to the demands of patronizing clients.

The African mask adorning Mrs. Mitra’s apartment wall indicates the irony of bourgeois pretending to share a connection with a far-off culture, which itself is sacrificed in the altar of bourgeois capitalism (the ‘mask’ symbol also reminded me of Sembene’s Black Girl). Such irony doesn’t pass judgment on the character, but rather points out the vacuity in her life; caught in her own prison of social niceties and job although she has broken the shackles of a loveless marriage. Furthermore, as the camera moves inside the luxury apartment an air of emptiness looms over the beautifully furnished rooms and magnificent art-works.

Sumit in his dialogues with his ‘self’ feels restless over enjoying the perks of living in the apartment. It’s a natural reaction considering his indoctrination into the ideology, followed by more real and burning questions. He wonders about the Party’s dissonance with the general public. Comrades risk their lives to stand for the cause. But over a time, the movement’s efforts to fight the status quo gets replaced with establishing its own brand of status quo. While the Party is strengthening its rhetoric, the impoverished and the starved keep dying in the streets. Moreover, as a documentary sequence exhibits (Simi’s characters interviews women from different social backgrounds), the views on gender equality and women’s rights didn’t seem to have gained much traction even among the so-called ‘revolutionary classes’. Hence, the helplessness and defeat Sumit feels is as sadly relevant as it did in the 1970s.

Padatik ends with a brilliantly staged and performed scene (both Bijon and Dhritiman were phenomenal) with Sumit and his father reaching out in solidarity or a reconciliation of sorts. In the penultimate scene, Sumit declares, “the party is nobody’s personal property. You’ve got to fight inside and outside”, insisting the need to not lose sight of the cause, and to keep ‘unlearning and learning’. Sumit’s fate does look bleak, but Mrinal Sen calls for a new beginning rather than pronouncing the death of his beliefs.

★★★★

Notes:

- Always Being Born, Mrinal Sen A Memoir, Stellar Publication

- India After Naxalbari: Unfinished History, Bernard D’Mello, Monthly Review Press, US (June 2018)

Padatik Trailer

Padatik (1973) Links: IMDB, Letterboxd

![Ken Russell Kraziness: The Music Lovers [1971]](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/vlcsnap-2020-03-31-19h42m43s105-768x324.jpg)