A few months ago, popular Film Scholar Professor Ira Bhaskar delivered a talk on “Popular Cinema and National Imagination.” In this talk, she addressed the question of the representation of National Idioms through the lens of Indian cinema. While her effort was well-intended, eventually the talk was generic and superficial owing to her lack of engagement with films that can actually be considered commercial cinema patronised by the audience, and hence her conception of “Popular Cinema” was left for her own discretion. The talk conveyed in broader strokes, making broad generalizations which could well be challenged and problematised. My observation from the talk was that Professor Ira Bhaskar tended to arm-twist the narrative to suit her political opinions, without caring for the dynamics that cinematic narratives can offer.

This article was originally framed as a series of questions framed at Professor Ira Bhaskar’s talk on Popular Cinema and Nationalist Imagination. So the series of questions became a point of inquiry to understand the nature of Popular Cinema since its evolution and how it promoted certain cultural tropes in terms of caste, class, religion, gender, etc. These questions can become a starting point for a larger and more sustained discourse on the socio-political and cultural representation in Indian cinema.

What is Popular Cinema?

Even though there is a general consensus that Popular Cinema simply refers to the piece of cinema which is consumed and commemorated by a considerable audience. But is Popular Cinema a static or monolithic category? The very idea of Popular Cinema has a recency bias, as what is popular today may not be popular tomorrow, and what was popular yesterday is not popular today.

A commercial failure like “Swades” (2004) is more popular than many of the major hits released in the same year, and conversely, the highest-grossing film of 1976, “Dus Numbari,” or 1984, “Tohfa,” is hardly remembered by the general folks. The present popularity of a film cannot be a parameter to choose a film as Popular Cinema. In that context, the Popular Cinema means two things: films which can be seen as the representative of the age it was made, and films which can be used as a tool of analysis for the socio-economic, cultural, and political discourse of that time. Using these criteria, we can choose films that can help us in the dissection of the multiple discourses and conceptual categories for our analysis.

Popular Cinema and Gender

The formative years of the Indian Cinema was dominated by mythologicals in the 1910’s and 1920’s, where the women had a specific role in upholding the values of Indian culture and civilization, which remains a major trope in the cinematic imagination of women wherein many of the films of these times had women longing, brooding, crying or acting as a moral support to the male protagonist. The trope of a vile Westernised woman who needs to be tamed and an ideal image of women as wife and mother remained a constant in Indian cinema, even after the representation of women in Indian cinema has undergone a sea of change over the years.

From films like “Mr. and Mrs 55” (1956) which came as a response to the Hindu Marriage Act, and which vilifies the feminist as home-breakers and justified even the violence committed by husband towards his wife, or films like “Insaniyat ke Dushman” (1987) and “Majaal” (1987) justifying the sexual assault of a girl, we have seen several problematic representation of women. We do find the influence of feminism and liberalism in the representation of women, but the orthodox representation of women’s war outweighs that of her emancipation, particularly in the realm of popular Cinema.

Popular Cinema and Borrowed Narratives

Since the early years of Indian Cinema, Indian films have taken influence from Western Cinema. In the absence of exposure to Western Cinema, many of these cinematic inspirations were able to scrape through without getting noticed. One of the earliest uproars about cinematic plagiarism was seen in the context of the film “Jagriti,” but interestingly the which featured songs like Sabarmati ke Sant and Aao baccho Tumhe Dikhaye Jhanki Hindustan ki. The said film was remade in Pakistan as “Bedari,” where Sabarmati ke Sant became Qaid e Aazam and Jhanki Hindustan ki became Sair Pakistan ki.

Throughout these years, there have been multiple occasions where both these countries have borrowed their nationalist tropes from each other and created their own nationalist imagination (“Dil Dil Pakistan” became “Dil Dil Hindustan,” “Made in India” became “Made in Pakistan”). Malik used the tune of the national anthem of Israel to ironically create a “patriotic song” for the film “Diljale” (1996). Where do these “Borrowed narratives of nationalism” feature in the nationalist imagination of India (&Pakistan) as well as other countries occasionally? Both countries share a long history of plagiarising songs and films from each other, and thus, in this case, Cinema is seen as a space where the question of Cultural Heritage and National Identities is raised.

Also Read: Cinema on Cinema: 30 Great Films About Films

A Pakistani film “Aaina” (1977) copies from multiple hindi films like “Aandhi,” “Kora Kagaz,” “Bobby” and “Aa Gale Lag Jaa,” emerges as an incomic film in the history of Pakistani cinema, and when the said film is copied in India in 1985 as “Pyar Jhukta Nahi”, it gives rise to a long tussle where both the countries try to claim the originality of their source material. Cinematic borrowings have been a part and parcel of Indian Cinema, which has raised the questions of ethics, copyright, and intellectual property in India. But in terms of cultural paradigm, it becomes a part of one’s identity politics. In the past few years, a similar tussle has been seen in the context of the “North-South debate,” wherein the Hindi Cinema is constantly put under the scanner.

Popular Cinema and Social Discourses

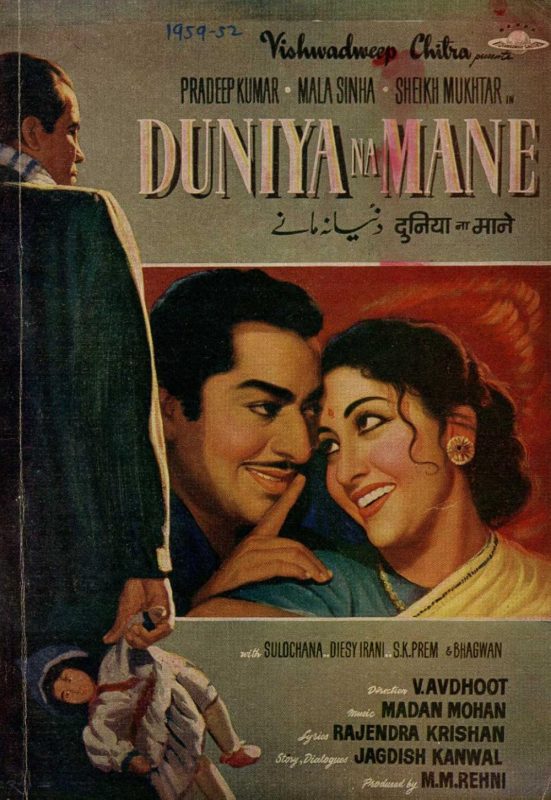

There has been a long debate regarding the purpose of cinema. Leaders like Mahatma Gandhi were critical of the ‘moral impact’ of cinema. While ‘Cinema for Cinema’ purpose is generally seen as the motto to justify the presence and relevance of art, Cinema has always been under the pressure to use it as a medium for social consciousness. In the initial years of Indian cinema, films were used to project the richness of Indian culture and literature, and to use them as a tool for socio-political awareness. Makers like V Shantaram with films like “Duniya na Maane” or “Tukaram” used cinema as a social tool.

Similarly, Sohrab Modi was using Historical films to spread ideas of communal harmony. In post-Independence India, we see the constant use of the Nehruvian ideas in Indian films, projecting ideas of socialism through films like “Naya Daur.” At times, we see the juxtaposition of Nehruvian socialism with the figure of Nehru in films like “Dharmaputra,” “Ab Dilli Door Nahi,” “Naunihal,” etc. By the 1970s, we see a segregation of Art and commercial cinema, with popular Cinema focusing on escapist cinema, leaving the social concerns to the parallel cinema. It is not that the commercial cinema was not socially aware, but these social discourses were overruled by the larger concern to entertain.

The tussle between the prerogative of cinema to inform or educate or maintain the fine balance between the two remains a concern even today. In the past few years, the films of Akshay Kumar and Ajay Devgn have shown an inclination towards nationalistic and social films. Politically speaking, the present political regime has seen similar types of films that reflect the mood of the modern political discourse. In today’s day and age similar juxtaposition of Narendra Modi is seen with the Idea of India on celluloid.

In that context, where do we draw the line regarding the depiction of political leaders in Cinema, to differentiate the envisioning of a political discourse from government propaganda? This question was palpable since the time media was controlled exclusively by the state and manipulated by the censors board to this era wherein the media is deliberately walking on the path of towing to the political regime and censor board and film federations and juries, whose integrity and political stance is constantly aligning with the present regime, as they are handpicked for the job by the regime.

Popular Cinema and National Unity

Indian Cinema is often seen as a cosmopolitan, macrocosm of the nation, which encompasses within its ambit different castes, classes, genders, ethnicities, etc. Cinema can be seen as a great enabler as well as a uniting factor for the whole nation. A very symbolic representation of the film can be seen in the film “Swades” (2004) in the song Ye Taara Wo Taara, where the protagonist uses the curtains of a moving theatre to teach caste equality and the unity of people. In “Filmistan,” cinema becomes a medium to unite India and Pakistan. “Lagaan” is similarly seen as a film that can be considered a symbol of an inclusive nation encompassing different castes, classes, and religions.

Ironically, “Lagaan” and “Gadar” (a Majoritarian, xenophobic film) were released on the same day, and despite all the acclaim received for the inclusive nationhood of “Lagaan,” “Gadar” earned three times as much as “Lagaan,” and spawned a sequel which earned 500 crores. Can the conflicting and contradictory imaginations of nationalism coexist with each other, and if yes, which imagination would we consider to be representative of the age? Till the 1980’s the names of the enemy countries were largely muted.

But in the 1990’s the representation of the enemy country became more and more pronounced with clear name-shaming of Pakistan. With some exceptions like “Main Hoon Na” and “Veer Zara” (both 2004), Pakistan remained the arch enemy in the cinematic representation. This trend has marked its return in the past few years with constant chest thumping, jingoistic films made, placing Pakistan as an enemy. Apart from them, the East vs West remains another popular trope of nationalist imagination since the pre-Independence times when the anti-colonial sentiments were at their peak. Even in the post-independence films, this divide is seen as a civilizational difference between the Indian and Western values, as seen in films like “Navrang” (1959), “Purab aur Paschim” (1970), “Pardes” (1997), “Namastey London” (2007), etc.

Going Beyond the Consumption of Cinema: Meaning Formation in Cinematic Production and Reception

Most of the works on cinema focus on the analysis of films as they are understood as a final product, which is to say that the emphasis lies on the consumption of cinema, and its meaning formation in the light of the discourse that emanates from it. But what about the meaning formation in the realm of the production and distribution of cinema? How Babubhai Patel fought to ban anti-Indian films way back in 1939, or how the Government of India banned the projection of “Bhool Na Jaana,” citing improved relations between India and China.

More Related: The Reincarnation Of Indian Cinema

To what extent the socio-cultural and national imagination reflected in Cinema is dictated by the needs of the society and the state, and the moulding of narratives according to the existing political atmosphere is something to ponder upon. Films do get made considering the present socio-political scenario in mind, and the makers do reflect their own ideologies through their cinema. There are makers in South like Pa.Ranjith or Vetrimaran or in Hindi Cinema like Anurag Kashyap, whose films are deeply ingrained in their worldview and ideology.

Also, the socio-political stance of a film and the people making them doesn’t remain constant. For example, “Shaurya” (2007), a film about the extra-judicial killing by the army, showed KK Menon as a bigot, who lets his personal hatred towards a particular ideology override his sensibility as a decorated army officer. In the past few years, in the light of the changing socio-political climate, the character is receiving a different kind of reception, and is being hailed as a hero, which was not the intention of the film.

Similarly, Suneil Shetty’s character in “Main Hoon Na” is seen by many as the real hero. Can we study the shift in the nationalist imagination even within the oeuvre of an artist with time, rather than assuming the nationalist imagination as a static entity? Even earlier, way back in the 1960s, “Shaheed” of Manoj Kumar reflected the revolutionary spirit and commitment to the nation in cinematic imagination, but the same maker shifted to making blatantly jingoistic and polemic nationalist films like “Purab aur Paschim” and “Kranti.” Similar sentiments can be seen in other makers and even artists who have moulded their work with time and with the changing society. Should their films be seen in the light of the maker’s intent and ideology?

In between these extreme stances, we have a group of filmmakers who believed in bridging the gap between art and commerce and maintain a delicate balance in their socio-political approach. These included Middle-Road Cinema’s exponents (Hrishikesh Mukherjee, Basu Chatterjee, Gulzar, etc) who not only provided a middle-class imagination of a nation but also provided a socio-political critique and commentary on the prevalent conditions of the nation (“Mere Apne,” “Satyakam,” “Maachis,” “Hu Tu Tu,” etc). We need to perceive the idea of cinematic imagination of the nation and society as a constantly negotiated and mediated discourse.

Popular Cinema and Caste

The caste question in Indian cinema is a very delicate one, as we see the dominance of upper-caste discourses dominating the cinematic imagination. In most of the Indian films, the protagonist were mostly identified with monosyllabic names which obscured their caste identities. The parallel cinema in India has been more assertive in showing the conditions of the marginalised sections of the society with films like “Aakrosh” (1980), “Ankur” (1974), “Paar” (1984), “Damul” (1985) and “Kamla” (1985) etc, but in the mainstream cinema, the question of caste was raised once in a while, and the impact was not always effective.

The commercial film makers have often been accused of using the caste question as a rhetoric rather than as a discourse. There was hardly any notable effort in mainstream cinema after “Sujata” (1960), either because of a lack of sustained effort from makers to talk about the caste issue, or is it because of the lack of impact of the films made on the caste issue in Hindi cinema during this time? (films like “Channi,” “Jag Utha Insan,” “Naya Kadam,” etc). In films like “Souten” (1983), untouchables are associated with black face, and their representation is highly cliché, representing self-sacrificing men or women who sacrifice their lives for the upper caste people, as also visible in all the above-mentioned commercial films.

“Chachi 420” (1997) was one of the rare films where the lower caste identity of the protagonist is emphasized without making a fuss about it. In the 21st century, with the emergence of multiplex era, the question of caste got better representation with many films either representing the question of caste like Lagaan (2001), “Swades” (2004), “Aarakshan” (2011), “Masaan” (2015), “Manjhi the Mountain Man” (2016), “Article 15” (2018), “Vedaa” (2024) etc. Many regional filmmakers like Pa.Ranjith and Nagrath Manjule have focused their narratives on the caste question with films like “Sairaat” (2016) and “Kaala” (2018), “Sarpatta Parambarai” (2021), and “Thangalan” (2024). Even though Hindi cinema has shown progress in terms of its representation in Indian cinema, there is yet to find a dedicated maker highlighting the caste issues.

What we see through this analysis is that popular cinema in India is both contested as well as diverse in its nature and features and cannot be pigeonhole into a monolithic category. The questions of gender, caste, class, etc, are interwined in the discourse of the making of a national, pan-Indian popular cinema.