The written word and the moving image have always had their entwining roots deeply entrenched in similar narrative codes, both functioning at the level of implication, connotation, and referentiality. But ever since the advent of cinema, they have been pitted against each other over formal and cultural peculiarities – hence engaging in a relationship deemed “overtly compatible, secretly hostile.” This sense of hostility springs forth from the misconstrued view of literature being the superior art form among the two, extending to the apparent artistic inferiority of cinematic adaptations, which seemingly “betray” its source material. But the idea of cinema as a potent and dynamic art form has successfully invaded popular perception over the last few decades – a phenomenon quite incomplete without the cinematic legacy left behind by a certain American filmmaker, who wields immense cultural currency: Kubrick. Stanley Kubrick’s most lauded works happen to be literary adaptations, and his cult status as a seminal auteur ushered in the notion of reading cinema as ‘text’: hence, problematizing the issues of authorship, artistic fidelity, and viewer response.

It was a sense of extraterrestrial awe, uncertainty, and perplexity which accorded the commercial success of ‘2001 : A Space Odyssey’ (1964); a film which uncovers layers of meaning, and mysteries, with each subsequent viewing- a kind of “double, triple, quadruple play”. The creative procedure that ‘2001′ underwent is a unique one: though loosely based on Arthur C. Clarke’s short story, ‘The Sentinel’ (1948), the script (jointly by Clarke and Kubrick) and the novel (solely by Clarke) were written simultaneously, where the latter was published four years after the movie, with significant departures. While Clarke’s ‘2001′ attempts to clear some of the film’s grand mysteries pertaining to the universe and its effects on mankind, Kubrick’s 2001 presents to the active viewer a scope for infinite possibilities, based on his/her visual perception coupled with “an awareness of cultural and emotional expectations”.

Speaking of the viewer as ‘reader’, it was Carole Berger’s 1978 essay “Viewing as Action : Film and Reader Response Criticism” which connected Stanley Fish’s theory of literature as “kinetic” art form to cinema for the first time. If one applies a crude amalgamation of Rosenblatt, Fish and Iser’s theories to viewer-response at the most rudimentary level, one can say that the viewer, while engaging in a transactional process of hermeneutics, becomes a member of an “interpretative community”, where subjective and configurative meaning is carved, constituting the gestalt of the viewing experience.

Now, returning to 2001, the responses to the same range from it being a rendition of the Greek epic Odyssey, a philosophical piece modeled after Friedrich Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra, to being a propaganda piece fueling the space Cold War between the then superpowers, perplexing generations of moviegoers and critics alike with its cryptic symbolism. The primary catalyst of 2001 is a black, rectangular monolith, the presence of which triggers two significant evolutionary leaps: from man-ape to human, and human to superhuman, as symbolized by the starchild at the end of the movie.

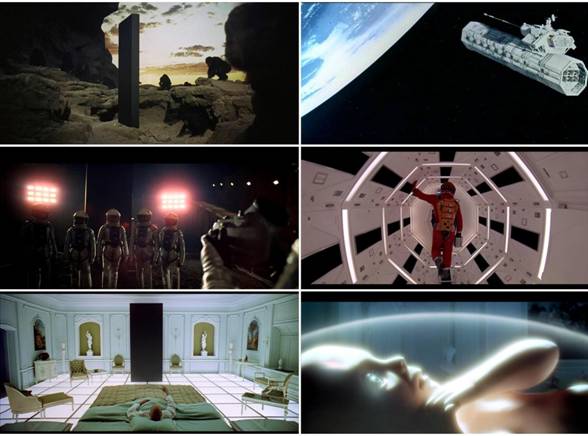

Figs. 1.1-1.6. The monolith first appears in front of the man-apes, triggering a 10,000 year leap to space-age man. Then, it appears on the first man-made moon-base Clavius, leading to the covert Jupiter mission on The Discovery. The final appearance of the monolith in front of the last surviving Discovery crew David Bowman, leads to the birth of the starchild, the post-human evolutionary stage of man.

Also Read: 2001: A Space Odyssey – Visual Analysis & Theme Explained

As to what the monolith and the movie, as a whole, symbolises, Peter Krämer conducted an audience response experiment named “Dear Mr. Kubrick : Audience Responses to 2001 : A Space Odyssey in the Late 1960’s”, based on fan-letters to Kubrick which applaud, interrogate and criticise the film, showcasing no substantial consensus as to what 2001 actually means. These divided responses range from expressions of livid confusion and dismissal, elaborate conspiracy theories, esoteric analogies, to an appreciation of the Stargate sequence by members of the hippie counterculture who viewed it as “The Ultimate Trip…but not of the space variety”. The reason why 2001 transcends articulation and escapes definitive attachment of meaning is explained wonderfully none other than by Kubrick himself :

2001… is a visual, nonverbal experience…I prefer not to discuss it’s meaning as it is highly subjective and will differ from viewer to viewer. In this sense, the film becomes anything the viewer sees in it. If the film stirs the emotions and penetrates the subconscious of the viewer, if it stimulates … his mythological and religious yearnings and impulses … it has succeeded.

Kubrick’s oeuvre stands testimony to his status among the highest echelon of film directors – he is an “auteur critic’s dream”. In the course of refashioning and deviating from the fabric of his source texts, he re-interprets and transforms them into a ‘text’ quintessentially Kubrickan. Two of the most archetypal examples of the same can be found in ‘The Shining’ (1980) and ‘A Clockwork Orange’ (1971), based on Stephen King and Anthony Burgess’ horror and dystopian novels respectively. It is now common knowledge that King absolutely abhors Kubrick’s Shining, embittered by how the characters of Jack and Wendy Torrance are coldly contrived, with no notable tragic arc making its mark on the narrative. Although he acknowledges the visually aesthetic shots that ‘The Shining’ offers, he calls it “a big beautiful Cadillac with no engine”, wherein the characters lack personal agency. On the other hand, the reputation of Kubrick’s ‘A Clockwork Orange’ being a cause célèbre eclipsed Burgess’ true novelistic intentions and literary merit, causing tension between the two. Though initially praising it as “relevant and poetic”, Burgess became increasingly ambivalent towards Kubrick’s treatment of the protagonist Alex, as the film omits the novel’s 21st chapter – considered integral to the character’s redemption by Burgess, hence destroying the novel’s moral integrity.

While it is indeed crucial to take King and Burgess’ criticisms into consideration, one must also take into account the idea of fidelity to adaptations and it’s lack thereof, the importance of artistic license and the excesses it might engender, and finally the role of collective authorship in terms of audience interpretation pertaining to the problematic areas of adaptation as a whole. ‘A Clockwork Orange’ aesthetically captures a depraved monologue in a dystopian setting; a spiritual wasteland created by Kubrick with images of unsettling violence and satirical humor: it is a film which overwhelms the senses. It explores the ethical ambiguities posited by the question of moral choice and free will – is Alex, in his natural disposition towards anarchy, drugs and ‘ultraviolence’, truer to his humanity than when he is ‘reformed’ by government experiments of mind control and forced psychological conditioning, as exhibited by the Ludovico treatment?

Also Read: Stanley Kubrick: Placing Gender Within Kubrickan Framework | High On Films

The absence of hope and possible redemption for Alex at the end has been accepted by audiences as the more “authentic” ending; many consider Burgess’ resolution to be “unconvincing and inconsistent with the style and intent of the book”. Moreover, Kubrick’s reliance on unconventional camera angles and his cryptic employment of literary and mythic allusions have enriched the layered intricacies of ‘A Clockwork Orange’, hence preventing it’s evolution into a “work too didactic to be artistic”.

Figs 1.7-1.19. A seventeen year old Alexander Delarge exercises violent delinquency along with his “droogs” by indulging in physical and sexual violence. Figs 1.10-1.12 Alex’s love for Beethoven is used against him when he is subjected to the Ludovico reform treatment, the failure of which leads to attempted suicide. In the end, Alex ironically muses, “I was cured after all.”

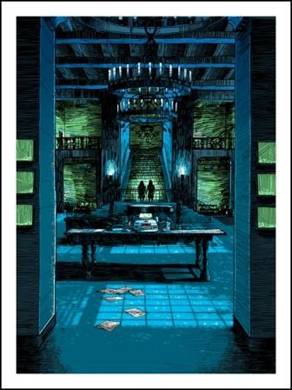

In his ‘A Cinema of Loneliness’ (1980), Robert Kolker calls ‘The Shining’ a conscious mockery on Kubrick’s part of the horror genre, which deals more with the gradual unfolding of derangement and it’s intensification in a supernatural setting -The Overlook Hotel- where Jack Torrance acts as caretaker along with his family during the winter of 1980. The cult status enjoyed by the film stems from its ingenious sense of ambiguity, and its capacity for accommodating a sweeping range of interpretations, mostly in relation to Kubrick’s apparent coding of subliminal messages embedded across the film narrative. This need for scavenging and investing meaning has reached rather obsessive heights; the primary reason behind which might be that, unlike ‘2001′, or ‘A Clockwork Orange’, King’s novel offers no answers – so utterly different and divergent is Kubrick’s reinterpretation of the same, that one doesn’t resemble the other in any way whatsoever. Artist Tim Doyle pays tribute to this phenomenon in his classic horror painting aptly titled “The Death of the Author” (2014), reinforcing the point that ‘The Shining’ is a “vast, open canvas” , where the author’s intention, (be it King or Kubrick), is remodeled in accordance with a viewer’s subjective perception, which might clash with another’s and still be deemed equally valid.

Fig. 1.20. The Death of the Author (2014)

This “Rashomon effect” found its culmination in a 2012 documentary directed by Rodney Ascher, encapsulating the wild conspiracy theories and perceived interpretations surrounding ‘The Shining.’ Christened ‘Room 237,’ the documentary spans five major theories, including the film being a critique on the Native American genocide, a theory based on a recurrence of relevant symbols and images. Another theory accuses Kubrick of faking footage of the historic Apollo 11 moon landing, wherein the film is a thickly veiled apology for the same.

Figs.1.20-1.23. Danny talks to his finger which symbolizes his imaginary friend, Tony, possibly indicating a psychological manifestation of parental abuse. Jack eyes the hedge maze aggressively which is connected to the Minotaur myth; Danny wears an Apollo 11 USA sweater, and finally, a photograph of Jack appears in the hotel in a Baphomet like posture from the July 4th Ball of 1921: is Jack the devil?

‘Shinologists’ have also experimented by playing the film forwards and backwards simultaneously, where the overlapping shots create “bizarre juxtapositions and startling synchronicities”. Admittedly, while some of these theories can be considered plausible, others point toward gross over-readings which seem ridiculously farfetched – Kubrick’s personal assistant ,Leon Vitali, who worked closely with him on the set of the film, recently debunked ‘Room 237′, as “pure gibberish.” So, can ‘The Shining’ be considered as an exemplar of the pitfalls of impressionistic reading, where the viewer excavates chasms of “indeterminacy” instead of simply filling the preexistent ones ?

When Kubrick unleashed his final cinematic work ‘Eyes Wide Shut’ in 1999, like all his previous films, it was grievously misunderstood by audiences and critics alike. Based on Arthur Schnitzler’s 1926 novella ‘Traumnovelle’ (Dream Story), Kubrick upholds a psychoanalytic parallel between the two, as the source story heavily borrowed from Freud’s theory of life (Eros) and death instincts (Thanatos). The task of transporting the overall historical, cultural and artistic context from the 1926 Viennese decadence to the postmodernist world of New York City was no mean feat – an adaptation requires functioning like a successful organ transplant, and Kubrick succeeds in creating a hermeneutic labyrinth with multiple exits. Derek O’ Connor terms it as a “saga of marital deception”, a “black valentine to the world”, where the mysteries envelop themselves in further mysteries. Despite being consistently faithful to Dream Story, contemporary re-interpretations of ‘Eyes Wide Shut’ are rife with over complicated theories indicating Kubrick’s use of subliminal references to myth, religion, art, and secret societies; along with the debate whether the entire experience was indeed a dream.

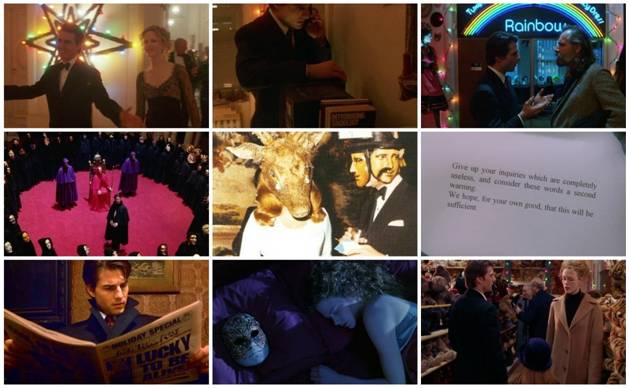

An essentially Kubrickan sense of ambiguity makes its presence felt in ‘Eyes Wide Shut’, demanding an in-depth scrutiny by the ‘active’ audience, who by now, have trained themselves to string together the breadcrumb trails scattered across the film’s visual and aural structure. In the opening sequence, we witness the lavish extravagance, along with a sense of civilized charm exuded by Victor Ziegler’s party, which is quickly revealed to be a façade concealing the ugly depravities and fetishes harbored by the elite : foreshadowing the Somertonville Mansion orgy later in the film. The presence of an unusual eight-point star as a Christmas decoration in Ziegler’s party has been interpreted by some as the star of Ishtar, the Mesopotamian goddess of fertility, love, sexuality and their perilous manifestations – a dominant theme which engulfs the lives of Alice (Nicole Kidman) and Bill Harford (Tom Cruise). The egoistic wound nursed by Bill is inflicted by his wife’s confession of an act of almost indiscretion, propelling him to exact revenge through a series of fantastical sexual encounters which are repeatedly thwarted, acting as instances of stagnation or death in desire.

Based on yet another subtle visual cue (a strategically placed book : Introducing Sociology), ‘Eyes Wide Shut’ can be read as a sociological document of class-based oppression, wherein the mere attempt of invading the space “where the rainbow ends” will inevitably result in social ejection, accompanied with a sense of constant danger. The nexus of Bill’s adventure is his infiltration into and subsequent discovery and humiliation at the masked orgy (an event solely accessible to the members of the elite), wherein the password for entry is “Fidelio” – a Beethoven opera about ritual sacrifice – is it a deliberate foreshadowing or a mere coincidence?

Figs. 1.24- 1.32. These visual clues spread across ‘Eyes Wide Shut’ invite a range of religious, psychological and sociological explications, including conspiracy theories surrounding occult secret societies and their covert practices.

Rainbows are traditionally associated with dissociation from the illusory world, (Fig.1.26), revealing the dark underbelly which lies beyond– a world inhabited by the participants of ritual orgies, riddled with dangers, threats and deceit (Figs.1.27-1.31). These events are not far from reality, as conspiracy theorists have connected these parties to that of the Rothschilds, who wore similar Venetian masks and held masked balls thematically rich with occult symbolism (Fig.1.28). Bill learns about Mandy’s death in a paper headlined “LUCKY TO BE ALIVE” (Fig.1.30) and his mask inexplicably appears next to a sleeping Alice (Fig.1.30); indicating the couples’ narrow escape from the clutches of the elite. But the final scene (Fig. 1.32) hints at their daughter, Helena, following two men who were formerly present at Zeigler’s party, permanently disappearing from the shot, while her parent appear nonchalant and self-absorbed – is this Kubrick’s way of pointing out the grim reality that awaits Helena, who is doomed to retrace her parents’ footsteps?

Alro Read: Best Stanley Kubrick Movies Ranked: From Great to Greatest

The history of adaptation theory has perpetually been problematic. This can be attributed to the presupposition of assuming literature as the vantage point for qualitative artistic comparison, hence relegating cinema to the realm of “a re-heated meal”; a pale, stale, imitation of the “original”. To accept novels and films as divergent, autonomous vehicles of meaning, and artistic worth, in their own right is instrumental to the understanding of adaptation politics and the problems it can pose – to what extent should narratology and intertextuality be adhered? Who is the author of a text like ‘Lolita’, and which version is worth consideration: Nabokov’s scintillating prose style (1955), Kubrick’s saga of censored passion (1962), or Adrian Lyne’s highly romanticized tragedy (1997)? Is a faithful adaptation the only desirable version of a text, and if so, where does the contemporary filmmaker stand today? These questions do not pinpoint towards a simplified, objective explanation, but rather remain perplexingly open-ended – but concurrently, one cannot sieve the fluid nature of adaptation and authorship through the grains of audience response, where the latter accommodates all the versions of ‘Lolita’ under one giant, all-encompassing umbrella of subjective aesthetics and interpretation, destabilizing the concept of “intentional fallacy”.

However, with regard to an auteurial sultan like Stanley Kubrick, can we afford to completely disregard his authorial intention? If not, to what extent can an unobjective dissection be sanctioned, minus the risks of wayward impressionism – how much is too much? Speaking of excesses, Kubrick’s obsession with authenticity and perfectionism, and his autocratic attitude during filming had turned into an actor’s nightmare : unending retakes of a single scene lasted for months, causing Tom Cruise to contract ulcers in the course of ‘Eyes Wide Shut’. Similarly, on the sets of ‘The Shining’, actress Shelley Duval started to lose clumps of her hair after Kubrick pressurized her beyond limits ; and the most iconic Ludovico scene from ‘A Clockwork Orange’ had rendered Malcolm McDowell almost partially blind. These instances are evidence to Kubrick’s deliberate intent of provoking a certain audience response, but of also allowing a viewer’s personal context to construct the philosophical meaning behind his/her cinematic experience.

Is there a Kubrick’s Code? It is no easy task to solve this elaborate labyrinth, which is rife with apparent exits and sudden dead ends. But Kubrickan cinema has been successful in breaking down the rigid boundaries of artistic mediums, uplifting cinema as a synesthesia of the visual, literary, oral, and aural, in the minds of the masses. Current events testify the same : ‘Loving Vincent’ (2017) is set to be the world’s very first fully painted feature film; a tribute to Van Gogh through the recreation of 62,450 handmade frames in oil paint. Though a tiny step towards the integration of the subjective aesthetics of painting and cinema, this will take response criticism and literary adaptation to heights never achieved before by opening stunningly colorful stargates of experience. Meanwhile, the rest is “rust and stardust.”

Links : IMDb, Wikipedia

Very nicely written.

Not a fan of Kubrick owing to “Too much” interpretation. Still respect him for being the best there for adapting a literary work yet make it his own.