Stanley Kubrick: Placing Gender Within Kubrickan Framework It can be stated with utmost certainty that, in the contemporary period, we have moved beyond the established notion that the very essence and idea of a film steadfastly revolve around storytelling, narrations as well as exclusive focus on character development. These very notions or perceived characteristics related to filmmaking associate film with entertainment as well as an activity that is primarily engaged in and suited for passing leisure hours by the consumers. Of the countless studies and academic researches associating film with text for analysis and exploring numerous and diverse concepts as well as stretching the discourse surrounding ‘film’ to the academic realm, it would be highly significant to discuss the works of Stanley Kubrick, a director who is widely renowned, admired and known for his ‘attention to detail’ enmeshed in his directorial skills.

Stanley Kubrick’s oeuvre is believed to focus on and highlight the debatable issues of the contemporary period discernible in his satire on the possible repercussions of using nuclear weapons led by urge and the propensity to compete; an exhibition of the innateness of the desire for exerting power and winning as seen in Dr. Strangelove (1964) and the process of constructing ‘dehumanization’ whose intricacies and details have been exceedingly celebrated in the film genres concerning war and witnessed an ‘explicit visual portrayal’ in Full Metal Jacket (1987).

With regard to how Kubrick’s films spread across complex, diverse and relevant themes; it would be remarkably noteworthy to underline those aspects, ideologies and issues that are addressed embedded in the directorial skills of the director; the issue of ‘gender’ being the primary issue in this very regard. The primary question that could be raised is how can a concept, a phenomenon and a notion as broad as gender be exhumed, categorized and subjected to further interrogations from the mosaic of themes intertwined with the broader subject constituting the subject of the respective films? Herein, it would be noteworthy to underline the existing ideologies related to the concept and most significantly how their prevalence, pervasiveness, representation and reinforcement are portrayed and presented by Kubrick through his ‘direction’ that has acquired the extolment to the degree of being labeled as ‘exemplary’ cutting across genres and conventions in the cinematic realm and subsequently set the benchmark concerning the incorporation of ‘attention to detail’ into the ‘directorial skills’ for the future.

Related Read to Stanley Kubrick: All Stanley Kubrick Movies Ranked

Sexuality and ‘female nudity’ constitute the primary theme that a substantial proportion of works by Kubrick that are explicitly represented through films such as ‘A Clockwork Orange’; ‘Eyes Wide Shut’ and ‘Dr. Strangelove’. Aside from the emphasis on nudity and its association with female subservience peppered with violence leading to unanimous uproar and disagreements amongst the audience over the release of ‘A Clockwork Orange’ as well as the tensions around the broader concept of ‘masculinity’ and its expression are contained in the theory of ‘heteronormativity’. The specificity of the focus and contextualisation of the scenes in the films combine the intricacies and nuances surrounding ‘gender’ with the Kubrickian directorial skill widely renowned for its ‘meticulous perfection, mastery of the technical aspects of filmmaking and atmospheric visual style in films across a range of genres’.

The enforced invisibility of women along with the depiction of ‘male gaze’ can be observed in Dr. Strangelove that visually portrays how political affairs in the backdrop of the Cold War and the discourse around nuclear armament constituting the primary theme of the film are steadfastly a ‘male domain’. The representation of the relationship between Buck Turgidson (played by George C. Scott) and Miss Scott (starring Tracy Reed) with the latter placed in a subservient role in relation to the former could be underlined from the references her position as Turgidson’s secretary as well as the scene showing her attending a telephone call. This scene involving Miss Scott combines the concept of ‘male gaze’ discernible with her appearance and the sole introduction to the viewers mingled with her conversation over telephone where her role was presented to as well as interpreted by the viewers as a ‘transmitter of information’.

However, the scene is noteworthy only for introducing the viewers to one of the primary male protagonists, Buck Turgidson (played by George C. Scott) and his response to the impending nuclear crisis. Here, the visual portrayal of Miss Scott combined with the delineation of her identity related to Turgidson as his secretary and a possible sexual partner cannot be translated into the glorification of the objectification or subservience but a deeper analysis of the scene and its contextualization set in the backdrop of a potential violation of the tenets of Cold War presents a socio-cultural setting where ‘subjectification’ of females, (sexual and in terms of contribution to the overall outcome of the narrative as highlighted through the direction) constitutes the ‘prime reality’ that in this case can be astutely observed through the overall representation of Miss Scott where the preservation about the discussions as well as opinions around armament for the males is implicit.

Related Read to Stanley Kubrick: The Viewer in Kubrickland: Solving Stanley Kubrick’s Hermeneutic Labryinth

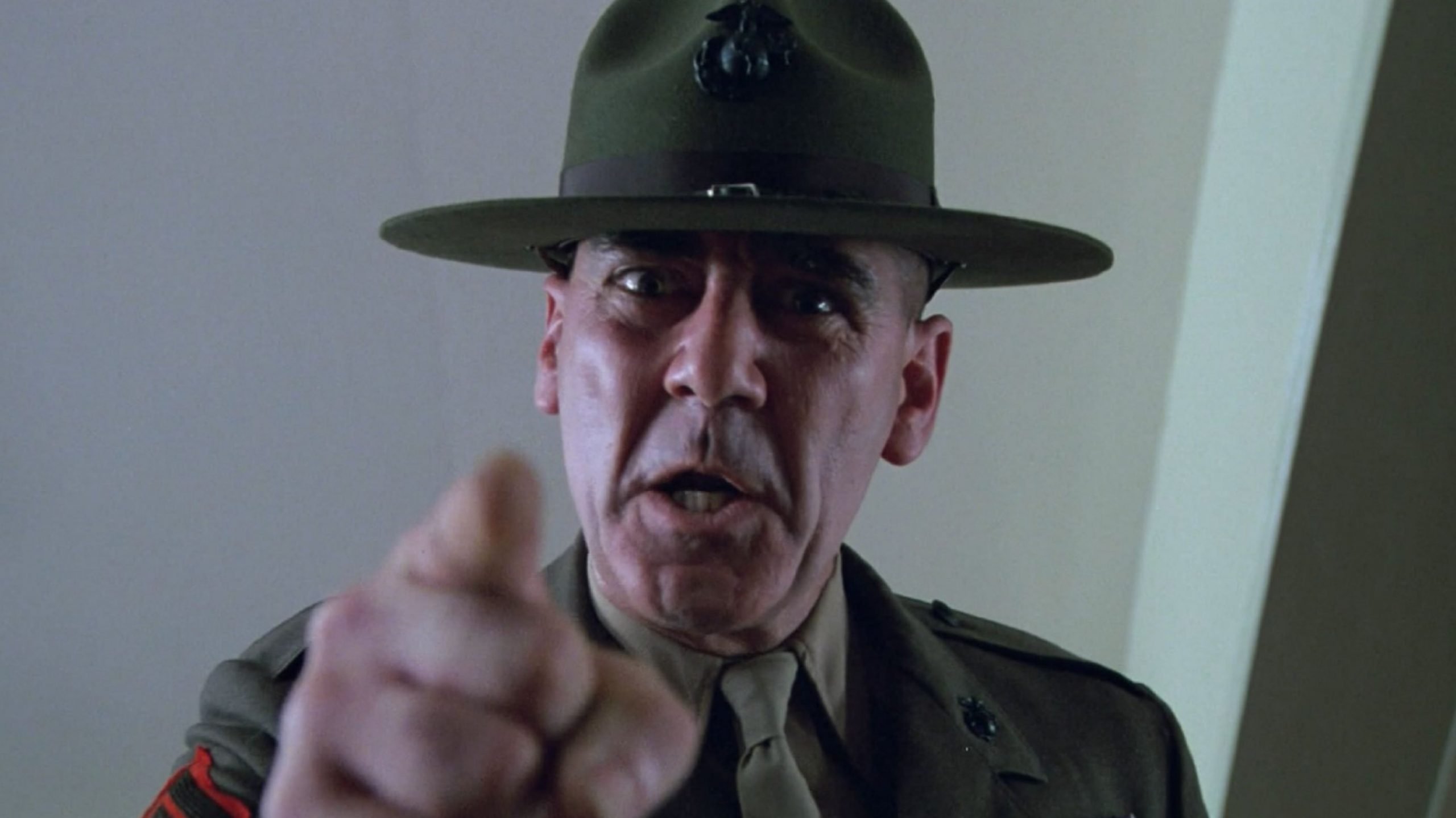

The tensions around masculinity have been explicitly portrayed in ‘Full Metal Jacket’ that can be derided as ‘patriarchal’ primary because of the absence of a female lead character and presence of a larger majority of male characters adhering to the internalized ideology that war is a ‘male domain’. In addition to positing the perceived reality of the training and construction of ‘able-bodied soldiers’ against the background of ‘Vietnam War’, the anxiety around retaining and restoring the ‘masculinity’ of the trainees and its characterization with that of a soldier could be highlighted by labeling the trainees as ‘ladies’ by the instructor as a sign of humiliation and demanding that their rifles be assigned female names by virtue of their deprivation of any form of engagement in sexual intercourse implying how women are ‘male possessions’. Here, Kubrick has combined his skills as a director to present a group of male trainees as the ‘prime characters of the scene’ deviating from the usual ‘war genres’ that places a significant emphasis on particular characters and underlines the character development.

The subservience of women underlines the tensions around losing masculinity that is simultaneous with the rigorous attempts at restoring and reinventing it by associating the subjugation of women with the usage of words like ‘ladies’ and ‘p*****s’ as potential threats to masculinity. However, it would be a misnomer to translate the attempts at explicitly detaching ‘maleness’ from the inescapable and inherent femaleness into the ‘inferiority’ of women, primary if the direction and the dialogues are situated within the broader framework of the film’s genre. Full Metal Jacket is a ‘war film’ that has been lauded over the decades for posing a criticism to the defining brutality of the Vietnam War placing the need to restore and express masculinity as a prerequisite to the eventual victory encapsulating the contribution of the characters to the outcome of the film. In this very respect, the plot and narrative structure of the film necessitates attempts at highlighting the hyper-masculinity and undermining any resemblance to the feminine characteristics in relation to their male counterparts constituted the key ways to ensure it that could be captured through the exemplary directorial skills of Kubrick immaculately represented through the characteristics of General Sergeant Hartman in the initial half of the film.

Related Read to Stanley Kubrick: 2001: A Space Odyssey – Visual Analysis & Theme Explained

‘Films’ directed by Stanley Kubrick, especially ‘A Clockwork Orange’ and ‘Eyes Wide Shut’ have been mired in prolonged scathing criticisms and controversies, primarily because of their erotic nature and explicitness in relation to female nudity and depiction of sexual harassment, as discernible in ‘A Clockwork Orange’. A blend of ‘female objectification’ blended with male gaze’ fitting into the broader spectrum of gender and ‘gendered differences’ fail to take into serious consideration the context in which the graphic representation and depiction take place and the role of direction in necessitating the significance of contextualization. This could be primarily observed in the introduction of ‘A Clockwork Orange’ in which Alex De Large’s monologue at the very outset of the film is indicative of the Droogs’ intention for committing ‘ultra-violence’, to the ‘audience’ was juxtaposed with the overall setting comprising of nude female mannequins with Alex’s feet over the torso of two figures lying in an overtly sexualized position. The very introduction of the film tantamount to Kubrick’s admirable skills in directing that combines and confirms the inevitability of the very act of ‘listening’ (the monologue) with ‘seeing’ the setting where the demonstration of the female figurines become symbolical of women constituting the passive agents of the society who are ‘acted upon’, thereby maintaining conformity with the concept of ‘dystopia’ with which the film deals.

Also Read: Il Maestro By Martin Scorsese: Federico Fellini And The Lost Magic Of Cinema

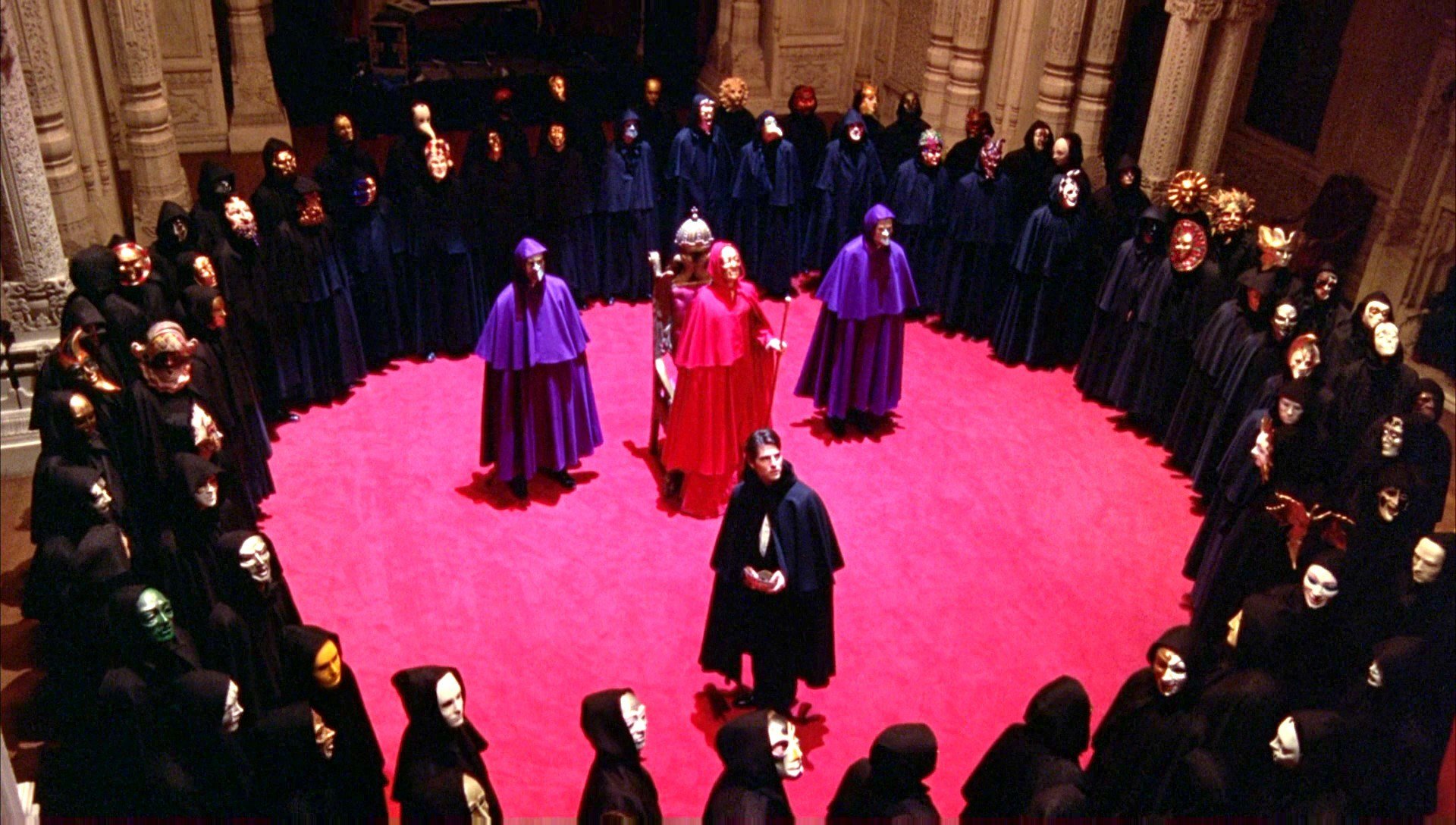

Consequently, the audience is engrossed in relating Alex’s persona with the presentation of female nudity and its further connection with the theme of the film showing how nudity, if and when placed in a proper ‘context’ cannot be associated with inferiority, objectification or overall subjugation of women but highlight a circumstance or setting where similar forms of female objectification and violence are normalized. A considerable degree of similarity could be observed in the ‘infamous’ orgy scene of ‘Eyes Wide Shut’ where in addition to focusing on female nudity ‘incongruently juxtaposed’ with the fully clothed males; the very representation of nudity becomes integral to a relatively smoother functioning and successful completion of the ritual. Here, the representation of females as portrayed in the film necessitates the presentation of the accentuated hierarchy between men and women along with the societal perception of the latter in an elitist societal set-up through a vivid illustration of female objectification in the form of nudity as distinctly captured in the Somerton ritual.

In this respect, Stanley Kubrick’s filmmaking methods can be interpreted to have exhibited enormous potential in addressing the broader and a complex concept like ‘gender’ that has always been the subject of debates, discussions, interpretations and deliberations in the realm of academia. A critical insight into the broader representation of the female characters and contextualization of the very depiction in the films directed by Kubrick highlight how the notions attached to ‘subordination’, ‘objectification’ and their association with discriminatory portrayal of women must not be generalized and situated in an accurate context. The latter encompasses the genre of a given film, the narrative forms and structures based on the broader theme as well as the direction that shapes and is shaped by them. In this regard, the terms, ‘imitable’ and ‘exemplary’ can be attached to Kubrick’s direction that addresses and highlights the established differences between males and females through placing the diverse references to females and their portrayal within the fold of the overall message that the film is attempting to portray thus making a subtle contribution to the outcome of the work.

![Garm Hava [1974]: On the Precipice of Belonging](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Garm-Hava-768x432.jpg)