“But in the end, one needs more courage to live than to kill himself” – Albert Camus

Arguably the most debated philosophical problem in history, its moral, ethical, and religious reasonings are entangled in mystery and misunderstanding; suicide is, due to a lack of words, confusing. Some cases hold meaning: an honorable death, an unfortunate last-straw attempt to escape from societal pressures or an act of patriotism, albeit the latter is quite a stretch. These acts are motivated by reasonings that could be, more or less, comprehended as an extreme solution to problems of varying degrees. The issue, however, arises when one kills oneself for an existential reason to free oneself from the unbearable burden of life. For such cases, it’s not the act of taking one’s life that must frighten us but rather when, why, and how the thought of taking one’s life takes shape in the mind. But absurd reasoning prevents it from being elucidated, an absence of rationality and genuine evidence making the least bit of sense. To even remotely entertain this notion of suicide will entail an endless barrage of arguments and contradictions that seem impossible to answer. The explanation might as well be a series of cryptic questions.

Philosophers have tried their hand at untangling this age-old debacle. Kant is of the position that suicide is immoral and unethical; to contemplate suicide is to spit on the face of God is how I’d phrase it. Isn’t it fair to assume it as a selfish and immoral act to spite God? Nietzsche finds some good in suicide, perceiving it as testament of unparalleled strength, our ability to take our lives whenever we want, however we want and wherever we want yet we do not. The fact we have such a choice and freedom over our existence is a reason to live. Camus’ argument, a personal favorite of mine, explains how once one takes a look behind the curtain of order and habit that gives meaning to a seemingly structured life, the absurdity of human life, the pang of existential loneliness and meaninglessness to the toil of life, overpowers them till the point where death seems more ideal than living on. The only solution is to accept this absurdity and live life bravely. To each their own perspectives, but the questions of suicide are not budged by their answers. What is it that compels a person to cheat the norm of naturally receding into the abyss they were born from? Was it a culmination of thoughts or did it magically pop up in the mind on a fine day? Is it morally abhorrent or simply misunderstood? Is the cause life, or its lack thereof?

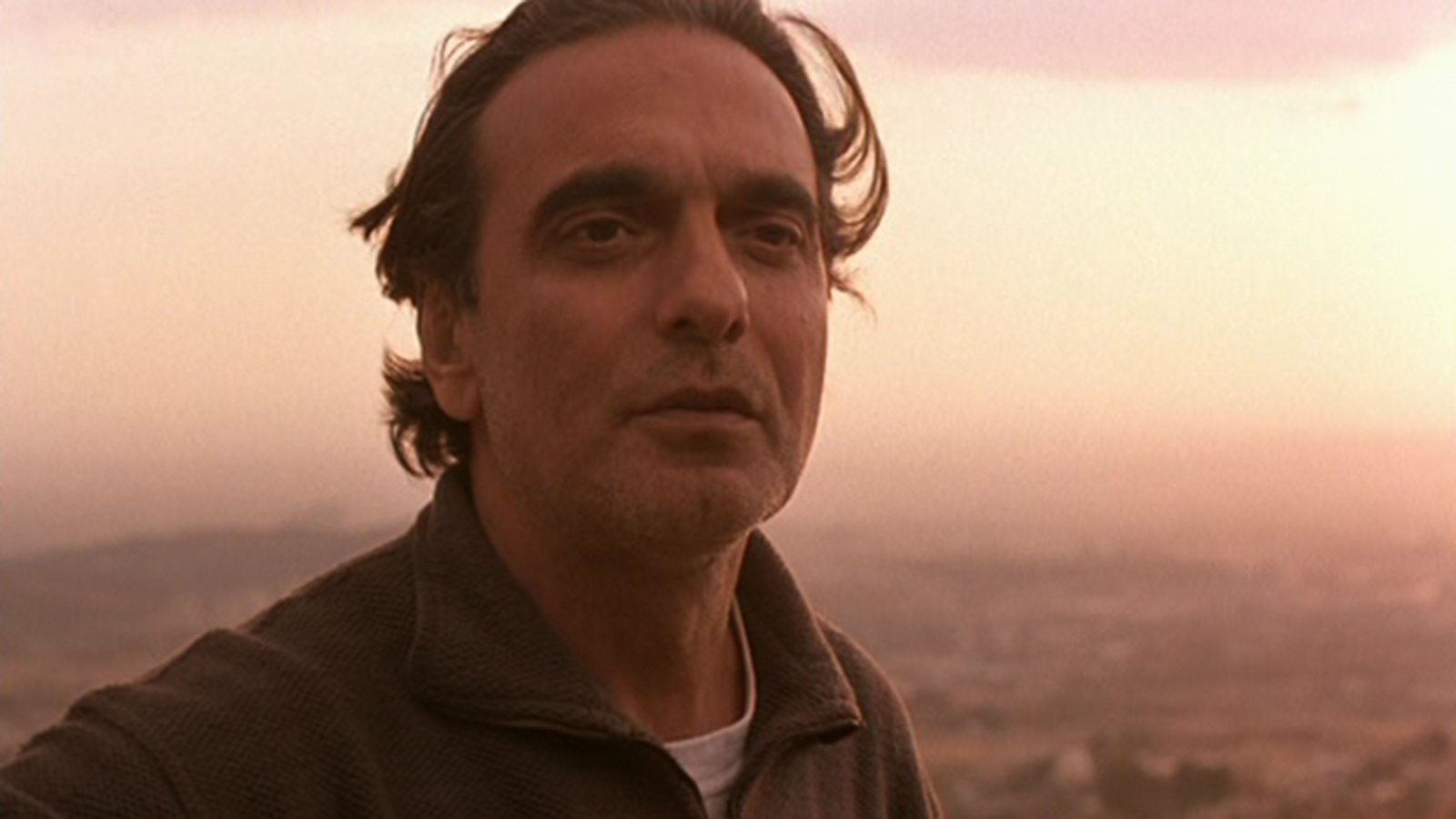

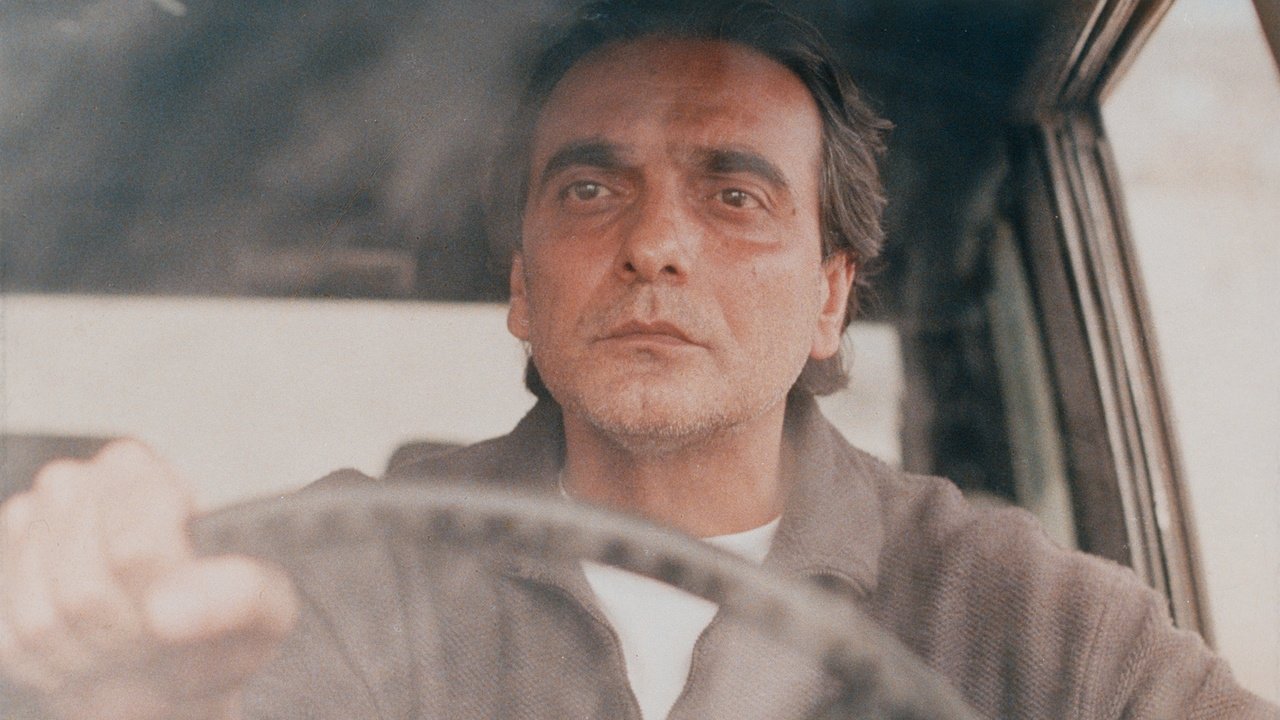

Abbas Kiarostami is on a mission to make sense of this dilemma in his Palme D’or winning Taste of Cherry, a humanely presented story of a man who drives around the dusty hills of Tehran to find someone who’s willing enough to bury him after he commits suicide. Brimming with realism and thoughtfully written, Kiarostami creates wonders from this deceivingly simple plot with a handful of unique characters and striking dialogue. From the exquisite yellow-hued cinematography that captures every trough and peak of the Iranian landscape to a captivating performance by Homayun Ershadi, Taste of Cherry is a profound, spiritual experience that never falls under the weight of the themes it wants to explore. It’s a film that puts forth the right questions to ponder on, touching on ideas of religion, mortality and life with utmost care and consideration. Kiarostami imbibes a sense of warmth and closeness that lingers long after the credits roll, as he takes the essential ideas of suicide and places it under the unbreakable compassion of human nature, exposing it’s absurdity and, ultimately, providing his answer with a climax that is both unexpected as it is life affirming.

Similar to Taste Of Cherry: 10 Best Iranian Movies Post Iranian Revolution 1990s

The film opens up to a man driving his car in the busy streets of Tehran. He looks out to the streets like he’s trying to find somebody. His intentions seem nefarious, driving creepily near the pavement, not uttering a word. Despite meeting a crowd of insistent laborers, ready to take up any task, he ignores them and drives off. The roads now give way to dirt paths with factories and huts dotting the scenery as the man is now cruising around the barren outskirts of Tehran with his eyes still scanning for something or someone. He’s met with hostility when he asks strangers to do a ‘favour’ for him, targeting down-on-luck workers, eavesdropping on their personal conversations and persuading them with money and safety but no luck. It seems like no one wants to help him. This 11-minute sequence before the title card appears, establishes the routine of this man and his. method of action. Our protagonist, Mr. Badii, is going to commit suicide and he needs someone to bury him. All they have to do is to come to the burial spot, which he has created, early next morning and say “Mr Badii” twice. If he replies, they have to help him up and if he doesn’t, they should cover him with 20 spadefuls of dirt and take a hefty reward. The film then follows Badii’s conversations with three people who have agreed to help him. The first person, a young Kurd cadet, who had hitched a ride so he could go back to the barracks, is frightened by Mr. Badii’s intentions and runs away in fear, tumbling down the hillside. After some searching, a poor seminarist now occupies the passenger seat but doesn’t agree to his demands because it violates his beliefs. Badii clashes with him, saying he’s only asked for his hands to do the work and that it’s of no use to convince him a way out of suicide. As the day is nearing to an end, Mr Badii is desperate but finally finds an old man, Mr Bagheri, who will do the deed. But the old man is insistent in preventing Mr Badii from killing himself, sharing an anecdote of how the taste of mulberry changed his outlook on life and his decision to hang himself. Mr Badii looks visibly shaken and when he drops Mr Bagheri at the museum where he works, adds that he should also throw two stones because he might be asleep. Later in the evening, Mr. Badii lies in the pit he has dug and looks up at the cloudy night. It’s the end. But there’s more to it than we expect.

Few films have the essence of being both staggeringly powerful and simplistic like Taste of Cherry, patiently taking its time to let events unfold and hitting a balance of seriousness and honesty that succeeds in never being overbearing. There’s always a human quality that gleams in Abbas Kiarostami’s films. His signature minimalist style of filmmaking, emphasizing on atmosphere, tone and dialogue, moves at a languid pace. His presentation is grounded, utilizing long one shot takes, stationary camera movements and lengthy conversations that inhibit a fly-on-the-wall feeling, as though the audience is a third passenger listening into the character’s ramblings. It’s a quiet celebration of life, covered in a serene bleakness, one that silently grabs our attention and doesn’t let go. As for the topic of suicide, Kiarostami is not only exploring the ideas of what makes it absurd but poses the question of whether its possible to convince someone out of suicide.

Mr Badii is wealthy and well-off yet he’s the most pessimistic man on screen. Not even money can cure his abstract sickness. He’s hell bent on killing himself but the reason for it is always hidden or, whenever he is asked, evaded. His intentions are irrelevant. While this starves us of a crucial piece of information that would provide some well-needed closure, Kiarostami’s conscious decision to not reveal it, makes Mr. Badii’s endeavors compelling, peeling back its absurdity at the same time. It also mirrors the fact that there is no real need to know why he’s going to kill himself because, as he mentions, no one can feel his pain. Mr. Badii’s ignorance keeps him from changing his mind but we must understand that suicide is not simply an act, it’s a conviction. Like the itch on the roof of your tongue, once the thought arrives, it sticks, it lingers and it never fades away. Bury it or distract it, it always comes back. Intentioned or not, the next step will be taken and there’s, sadly, no changing that. So, with that out of the way, hope lies in convincing Mr. Badii what he’ll miss once he leaves the plane of existence.

The cadet, the seminarist and the old man represents each of the age’s perception to the idea of suicide. The young boy, life yet to be journeyed and innocence intact, compares it to murder. His reaction was justified; death should never concern the mind of a growing child. The middle-aged seminarist sheds light onto the religious lines Mr. Badii would be crossing. He is more mature, thoughtful and listens intently to Mr. Badii’s rationale. But the seminarist is a man of God so he politely declines the offer. The old man provides some much needed relief. He accepts Mr. Badii’s demands but he’s confident that he will only help him up the next morning and nothing more. The old man is wise and compassionate, doing everything in his power to pry a few words out of Mr Badii even after repeatedly telling the old man he doesn’t care. The old man had been in Mr. Badii’s place and that clicked something in him. Years ago as a young man, it’s the taste of a mulberry that opened the man’s eyes. A small, almost insignificant foodstuff stopped the itch in his mind. The absurdity of suicide ever so slightly appears itself here. Mr. Badii will be abandoning the eternal beauty of nature, humanity and life for his reasons. The happy children in the playground, the patterns of crows in the dusk sky, red earth and sunsets, bulldozers, granite, cigarettes and God, humans with their human actions, will all vanish. Opportunities will arrive for redeeming himself. A second chance is always waiting. Should he sacrifice everything, the taste of mulberry, of life, for a purpose he will never tell? He questions his decisions when he sits on the bench watching the evening sky, a moment of self-reflexivity and peace. A permanent solution to a temporary problem; the old saying never felt more truthful as it does now.

Related Read To Taste Of Cherry: 10 Best Majid Majidi Films

But Kiarostami has more tricks, or ideas, up his sleeve. Mr. Badii does go to his final resting place. He lays in his grave, watching clouds mingle under the moon-lit sky. A distant storm is heard. Mr. Badii closes his eyes and the screen fades to black. The film ends but the story goes on. The last few minutes are shot using a grainy camcorder. No golden tint, no steady shots or even the recognizable Range Rover. We see the director, Abbas Kiarostami himself, talking with Homayun Ershadi and announcing that he came here for a sound take. An odd choice to end a film but it’s the climax it deserves, a fourth wall break that echoes of Alejandro Jodorowsky’s The Holy Mountain. As Kiarostami breaks the immersion so does he break the medium that kept the ideas of the film, static and inconsequential. He destroys the boundaries between fiction and reality, finding its way into our lives.The ruse that it’s just a film gives respite to the audience but the essence still remains and it’s incredibly liberating. The ending is what we make of it. Mr. Badii will live as long as we think we will and it encapsulates the absurdity perfectly. Perhaps we’d like to believe that Mr Badii wasn’t searching for someone to bury him but to save him. He might be fed up with his modern life but there’s a sliver of hope that humanity will rescue him. Mankind will forever be plagued by the very thought of suicide but we must always find ways of understanding it. Our perspectives are what matters but we must toil hard for it. Life isn’t hard. Human beings just made it that way.

Taste of Cherry is an exploration into the fragility and worth of the human spirit, the empathy that lives in each and every one of us, how compassion overflows from our hearts when we see others in trouble and our constant pursuit for answers. Kiarostami never belittles the audience by preaching on why suicide is bad, instead, he arranges the arguments in a way there is reason from both sides and the answer we take is the one we truly believe in.

![World War III [2022]: ‘Venice’ Review – A sharp and poignant tale of a film crew member pushed to the breaking point](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/World-War-III-2022-Movie-Review-1-768x512.jpg)