That They May Face the Rising Sun (2023) Review: John McGahern, author of The Barracks, The Dark, and Amongst Women, is among the most prevalent writers in Irish literature. And who better to make the adaptation of his final 2002 novel than Pat Collins—director of the documentary John McGahern: A Private World (2005)? Having grown up in a similar rural Irish community, Collins is best suited to understanding the intricacies, values, and routines of the simple farmer life, where everybody knows everybody else. Where community really is everything.

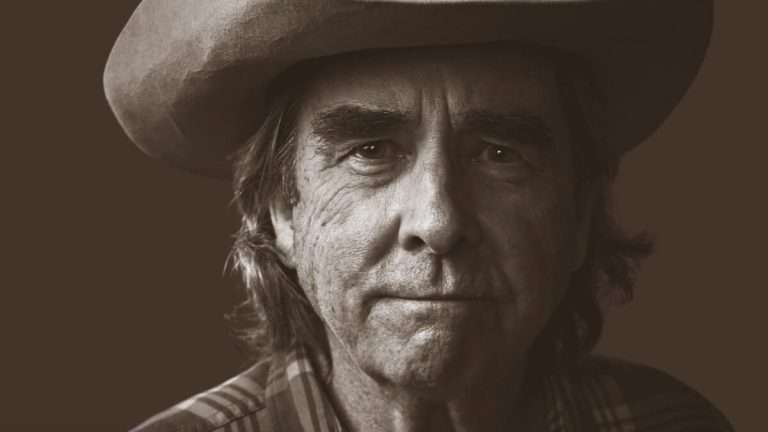

That They May Face the Rising Sun is a down-to-earth, self-conscious novel that makes for a reflective movie. The characters—Joe and his wife Kate (played by Barry Ward and Anna Berderke)—mirror McGahern’s own past in that they have moved from London to their countrified hometown, and Joe spends his days writing his next novel. When his neighbors ask, “Does anything happen?” in his novel, Joe replies it’s nothing dramatic—“just day-to-day stuff.” Just like the movie we’re watching.

This meta-narrative aspect, born from McGahern’s partially autobiographical book, gives That They May Face the Rising Sun another level of inwardness. Not only do we get gorgeous landscape shots that sing an ode to nature and sit in on the neighbors dropping by for tea, but we can feel that the story comes from something experienced firsthand. The fact it was McGahern’s final novel weighs They May Face the Rising Sun with even more importance, going hand-in-hand with the sensation of finality present throughout the 108-minute runtime.

Besides Joe and Kate, the community is made up of old men walking their last home run, with no next generation to carry on their traditions, the 21st century leaving rural Ireland firmly behind. “No need to be writing letters anymore,” Joe reads aloud in a palpable key of sadness. It’s all phones now. It’s technology and social media and rushing to catch the next train. There is no time for craft or intimacy anymore.

Although it’s an overall friendly and wholesome movie, where Joe shuffles out favors while his wife keeps bees in the garden, you can’t help but sense a faint tremor of resentment, of bemusement, in the air. This is likely due to Joe’s audacity to leave his homeland and come back again—to have been seduced by the artist lifestyle in a glittering, overcrowded London and then knock on their doors once more. For all its beauty and delicacy, there is something coarse about this world, where rough-skinned men labor for just enough to keep a roof over their heads and then walk to their death out of fear of being perceived as “gone soft.”

Thanks to Richard Kendrick’s minimalistic approach to cinematography, still shots lingering on views of the mountains, you can almost feel the draught of the rooms—smell the fresh autumn air and the scent of stale cigarettes. Among these fields, away from London (the context of which acts as an amplifying juxtaposition), Joe can close his eyes and listen to the birdsong before tapping on his typewriter. The sounds of the old world. Here, he can witness the passing of seasons, which he documents for us, writing, “the summer ended, winter not yet in” as we hold on to images of an orange-hued forest. That They May Face the Rising Sun essentially feels like a meditation in movie form, a celebration of the art of noticing.

A loose structure is given to the vaguely plotted book through Joe’s writing, which we’re given readings of in intervals, Joe pausing his life to sit at his desk. Accompanying this is usually a soft, somber piano score from Irene and Linda Buckley—bittersweet in that nostalgic sort of way. If Joe and Kate have found such peace in the family values and sweeping hills of 1980s Ireland, then what is that note of melancholy we hear ringing through the movie? It’s faint but certainly present, layering onto that hazy sense of an ending.

The people of this lakeside are few and far between, and although they all know each other well, there’s still an impression of loneliness for viewers who are used to urban living. All of Joe’s friends are aging men, living alone in shabby houses, sitting silently with their pints. It seems only Joe and Kate are learning how to hand weave, home grow, and tend the land, and despite their appreciation of it, the opportunity to take over an art gallery in London still hangs over their heads.

“You wouldn’t leave me, Joe? You wouldn’t forget me?” asks one of his white-haired friends, believing Joe might go to the shop and forget to pick him up afterward. Days later, Joe is preparing the man’s body for burial, giving his forlorn question an even more heart-breaking quality. Joe won’t forget his roots and let all the old men—once young and full of life, like Joe, now left with nothing—sink into an abyss of forgotten memory, will he?

No doubt, due to his own upbringing, Collins honors this ritualistic land where tradition is held on a sacred level, as well as the people who maintain it. Published as By the Lake in America, the novel’s captivating imagery is brought to life through the camera, where still water hums in stunning clarity beneath the dusky sky. That They May Face the Rising Sun takes Irish cinema’s usual love for simple living and natural beauty (think: The Banshees of Inisherin) and goes one step further, inviting us in for a cup of tea with the locals, privileged to be let in this secret, peaceful world. It can be mournful at times, but “what use is regret? You can’t light a fire with regret.”

![Marlina the Murderer in Four Acts [2017]: ‘TIFF’ Review](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/TIFF_HIGH_ON_FILMS_marlinathemurdererinfouracts_04-768x384.jpg)

![Beneath the Shadow [2020]: ‘NYAFF’ Review – A Slow-Burn Queer Drama That Withers Before Bloom](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/BENEATH-THE-SHADOW-Movie-Review-highonfilms-3-768x512.jpg)

![Hilda and the Mountain King [2021] Review – A beautifully animated film that is optimistic about a better world](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Hilda-and-the-Mountain-King-1-768x432.jpg)