Sidney Lumet was one of the most important American directors to ever live. Evident through his immense filmography, he was a key director of dramas and thrillers throughout a number of decades, particularly in the ‘70s with regarded classics such as Network, Serpico, and Dog Day Afternoon – this series will cover some of his lesser known directorial efforts that perhaps should be as esteemed and as discussed as these works.

Years of prolific work in Off-Broadway and then in television, Sidney Lumet made an impression with his directorial debut in 1957 with 12 Angry Men, which was critically lauded for the young filmmaker at the time of its release and to this day (currently sitting comfortably as the 5th most highly rated film on IMDb). Seven years later, and seven films later, Lumet had kept up a steady pace of releasing a film every year – the realist dramas he was making this early on in his career were quite theatrical and kept the drama within a minimal amount of scene and sets (just like how 12 Angry Men effectively takes place in one location).

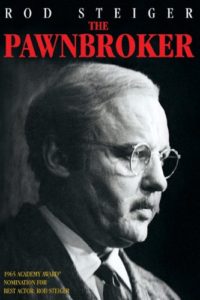

The same minimal and theatrical setting is utilised in The Pawnbroker, with the large majority of the film taken place in this one location, busy with all sorts of quirky and perhaps useless items strewn all over the shop. Similarly to 12 Angry Men, The Pawnbroker is made up of lengthy scenes to piece together its drama, which works when it’s at its most engaging and brings in the audience into the shop and into the story, though fails during the more sluggish moments where not much happens (or when something does happen, but it doesn’t add much on the story).

The tight setting of the pawn-shop is at times punctuated by Holocaust flashbacks, sometimes wildly implemented through single-frame subliminal editing to show Sol’s psychological reaction to the world having been put through hell. This is at its most apparent when Sol is flirted with by a woman customer, whose gradual stripping is a reminder of the stripping of his wife by officers in the camps.

Despite the film’s strengths and good intentions, it can be a slog at times, feeling too stuffy being confined in the one room for the large part of two hours. These filler moments aren’t exactly validated by an ending that just packs on the misery and gloom, but doesn’t seem to reach for much of a catharsis or even resolution. It seems like the reason that a socially conscious film like this being made so soon after World War 2 and so close to the Vietnam War isn’t exactly revealed. But even if the ending feels a little inconclusive and unsatisfying, it’s still produced in a way that showcases Lumet’s skills, particularly in providing a memorable and effective ending to watch.

As it goes with Lumet’s confined early works, his portrayal of New York and its inhabitants and their culture is done mostly through an internal manner, showing the diverse neighbourhood of the Harlem pawnshop, but very rarely exiting to show a wider outside portrayal of the city – Lumet would continue with this method with Dog Day Afternoon and Prince of the City, but more contained and interior films like The Pawnbroker relied more on the people than the buildings to tell the tale of New York.

![A Ghost Story [2017]: Sundance Film Festival Review](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/a-ghost-story-768x578.jpg)

![It Is In Us All [2022] ‘SXSW’ Review – A Beautifully Shot Assiduous Thriller](https://79468c92.delivery.rocketcdn.me/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/It-Is-In-Us-All-2022-768x432.jpg)