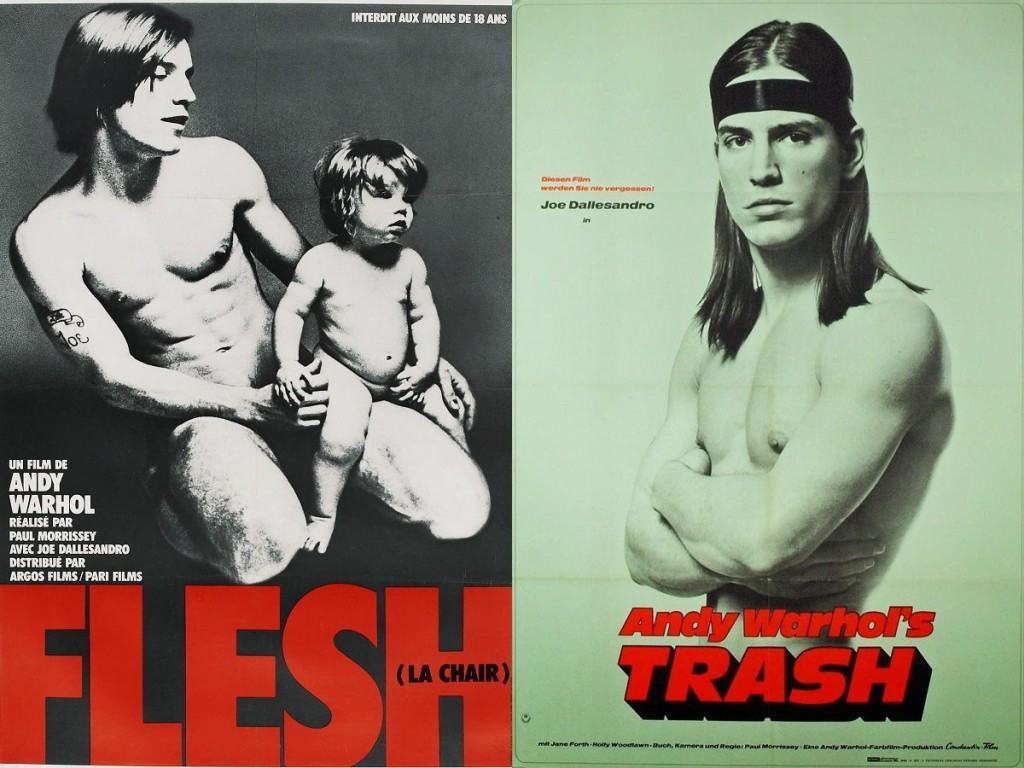

Although he would rather not be associated with the independent scene, Paul Morrissey’s no-budget films Flesh (1968) and Trash (1970) could be credited with introducing to the cinema a more experimental and more life-like portrayal of the counterculture movement in America, one that was far less concerned about narrative concepts and more about directly observing the lives of the people amidst this movement.

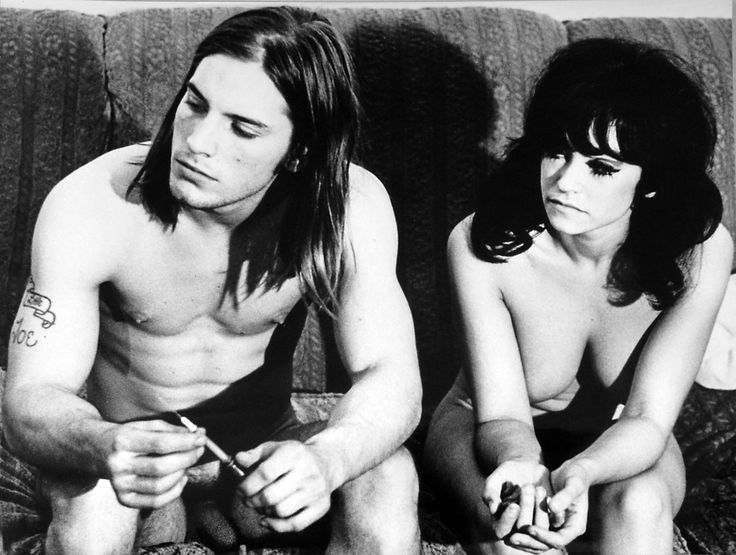

Both films star Joe Dallesandro as leading man Joe, one of the most ethereal characters to grace the cinema screen, a young man who’s so faded, he’s barely even there. Joe seems to glide purposelessly through each scene that he appears in, only commentating on his environments when he deems it necessary. Flesh opens, and closes, on a close-up of Joe’s resting face as he lies in bed, with everything in between showing us a day in the life of this New York hustler.

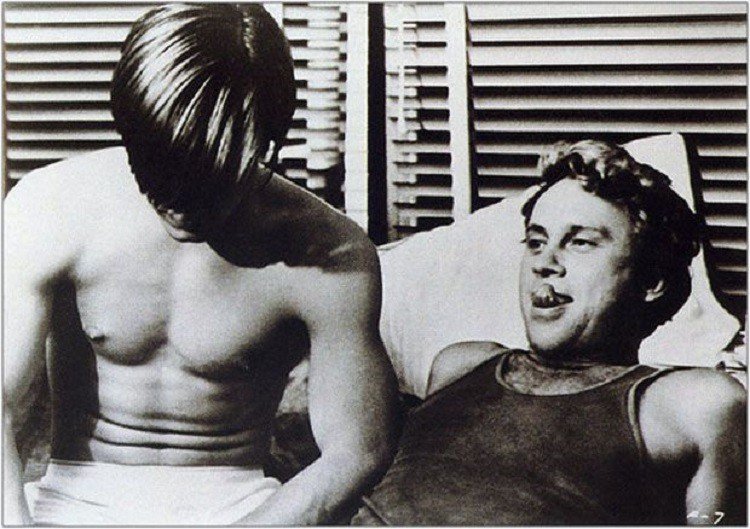

Among many things, this slice of life (as misleadingly pointless and minimalistic as it may seem) shows the warped fascination the high-class had with this particular lower class brand of the counterculture, as explicitly glimpsed in Flesh when an elderly man utilises Joe’s prostitution, not for sex, but to instruct Joe into different Olympian positions whilst commenting on the history of the male physique.

Like in many of the scenes in Flesh, but especially this one, the experimental editing is designed by the camera being turned off during filming at irregular times, rather than traditional editing in post-production. This exemplifies Joe’s haziness towards his profession, as well as his rejection of the elderly outsider’s fascination, the film’s cutting in and out refer to his placid and ethereal state of mind that results in his (and the film’s) wavering concentration. It’s experimental techniques like this that inform Flesh’s hazy and lazy portrayal of this culture that illustrates this mood of indifference, and it shows a key Morrissey theme that this young culture had little interest in being gawked at by outsiders.

The follow-up, Trash, continues following the life of Joe and his uncaring descent further into squalidity, as the title suggests. Joe and his new reluctant squeeze/roommate Holly (Holly Woodlawn) literally pick through trash to find stuff to keep and use (or to sell, with most of Joe’s income spent on heroin), yet the high-class have a fascination with them. A young socialite reacts oddly after catching Joe burglarizing her house by allowing him to stay and make himself at home, which eventually culminates with him doing heroin for the spectacle of herself and especially her husband. Unlike the scene in Flesh with the elderly and unusual trick, this scene has a more rounded conclusion – Joe is kicked out of the house immediately after taking heroin because his habit caused an argument amongst the husband and wife. This goes for most of the scenes in Trash and it’s what differentiates its narrative style from Flesh’s – there is less vagueness and more conclusiveness to these mini-narratives, but they often end with the characters in incredibly uncomfortable and awkward situations. It happens again when Joe and Holly’s welfare inspector offers them unwarranted welfare simply in exchange for Holly’s silver shoes, though she proudly refuses, leaving both of them without the government-issued money they so badly need.

Trash’s structure may seem as fluid as Flesh’s, but there is certainly a little more rigidness in its stylistic construction, as well as its adherence to building up to emotionally heightened climaxes in many of its long sequences. There is evidently less tampering with bizarre, off-putting, and obscuring filmic techniques like in Flesh, with instead more of a keen concentration on the plot unfolding before the camera. Unlike Flesh, Trash unveils its messages about this culture through its story rather than in its stylistic design, but its overall narrative still lacks much of a conventional concrete structure.

Both of these films are remarkable in how they portray the young Americans of the counterculture, as well as how they were viewed with fascination by the analytical high-class that preceded them. The cast and crew have avoided taking a middle-class perspective of the people of this new American culture, instead, they have mimicked the roughness of their lifestyles in the rugged production style of these films. The sheen of filmmaking has been thoroughly eroded and given way to authenticity in the naturalism, in both content and form. However, there’s even something metatextual about these films, as the audience members themselves are likewise intrigued outsider observers of this exclusive demographic.

As in-depth as these two films get into the languid lives of these young adults, there is always a sense of satire permeated in every scene. Morrissey admits that these films are comedies (as were most of his films) and given that he was an outsider of this movement as a devote Catholic who observed the culture with sober and critical eyes, he employed a Dadaist realism in his portrayals of this movement, using repetition, tedium, long empty silences, and conversational red herrings to humorously convey the boredom and the quest of his characters to assuage it. Watching people do nothing has never been so interesting.