For over 30 years, Texan auteur Richard Linklater has been crafting experiments in time: subtle, observational pieces that explore how time influences changes in ourselves. This is most famously exemplified in Boyhood, the voraciously acclaimed 2014 drama that took 12 years to film, but also in the Before trilogy, in which Julie Delpy and Ethan Hawke play the same lovers in three films made nine years apart, and his breakthrough Slacker, an unorthodox portrait of a lazy day-in-the-life. Each of these works stands as an epoch moment in American independent cinema.

Linklater came to prominence around the same time as Quentin Tarantino or Kevin Smith but has become more of a Steven Soderbergh type as the years have progressed – less of an ideologue with his thematic preoccupations and instead willing to flex his muscles within traditional studio systems and other writers’s scripts. Whether it’s the broad comedy School of Rock or failed Oscar-bait Where’d You Bo, Bernadette? all of his films maintain a naturalistic style and playful structure, which define his best films. And that’s not even beginning to mention his groundbreaking experiments with rotoscope animation or underrated pictures like Me and Orson Welles. It is a vast filmography to dive into and a true delight once you embrace Linklater’s passions and visual ticks. In anticipation of his new film Hit Man’s (long-delayed) release on Netflix this summer, let’s count down his finest hours as director.

10. Me and Orson Welles (2008)

Intended as a breakthrough dramatic role for teen heartthrob Zac Efron, 2008’s Me, and Orson Welles has receded into relative obscurity since its release. Even when it came, it received less flowers than David Fincher’s Mank, another film that grapples with Welles as an artist and icon, which is a shame because this is far more satisfactory. Like in Mank, Welles stands on the periphery of the plot here. Played with breezy charisma by Christian McKay, he is putting on a legendary reworking of Julius Caesar and takes a younger cast member under his wing (Efron).

The movie’s scenes flicker between a loving retelling of this storied production and Efron’s burgeoning love affair with a production assistant played by Claire Danes. The ties between love and art, and how one influences the other, is familiar territory but solidly integrated within a charming screenplay. The sense of humor is amiable and genteel as opposed to the slacker comedy of his early films or the raucous energy of School of Rock, and it’s refreshing to see Linklater operate within new disciplines. In another life, Linklater could have been a rock-solid director of this sort of Oscar-friendly fare. Thankfully, he found more interesting avenues to explore, but Me and Orson Welles is nevertheless an entertaining curio.

9. Bernie (2011)

Linklater tackles another true story in Bernie, though this one’s far away from the glitz and glamour of Orson Welles. Jack Black stars as Bernie Tiede, a flamboyant mortician who falls under the spell of enigmatic older resident Marjorie Nugent (Shirley MacLaine) in an ultimately fatal comedy thriller. It doesn’t sound like classic Linklater, but the setting of his native Texas gives the movie an endearingly homespun feel. The faux-documentary structure intersperses the narrative with fictional talking head testimonies, imbuing the narrative with a sense of local gossip. Bernie and Marjorie are people defined by their reputations, and the ways in which the power dynamic between them shifts the perception of others is gripping to watch and a genuine testament to MacLaine and Black’s superlative skills as performers.

A further personal gloss is added when you discover Linklater’s relationship with the real-life Bernie, which developed closely over the course of making the film. Tiede even stayed in the director’s garage for a short period. Despite this, the film never becomes overly sympathetic to its protagonist. It is not immune to his charm and doesn’t shy away from his sins. It’s a skillful character study packaged within a riveting black comedy and one of the more overlooked entries in the Linklater oeuvre.

8. Tape (2001)

Tape is a watertight three-handler powered by terrific performances from some defining stars of ‘90s alternative cinema: Ethan Hawke, Uma Thurman, and Robert Sean Leonard. Adapted from a play, its central conceit is nevertheless quintessential Linklater, blending experiments in time (the film chronicles 80 minutes in real time) with formal experimentation, the title partially alludes to the camcorder Linklater shot it on. The result falls somewhere between a taut psychological thriller and the world’s greatest TV bottle episode, punctuated with moments of real tension.

Single-location films always act as a litmus test for a director’s ability to block and direct scenes. Linklater successfully maintains the claustrophobia of the film’s only set (a dingy motel room) whilst maintaining audience engagement. The smart interplay between extended long takes and meticulous editing crafts something that never relents in its tension as it explores themes of manipulation and false memory. The central question appears to be the extent to which our memories dictate our sense of self, which recalls the Before sequels, among others. Tape is another excellent example of Linklater embedding his themes into a genre potboiler and a stellar entry into his 2000s work.

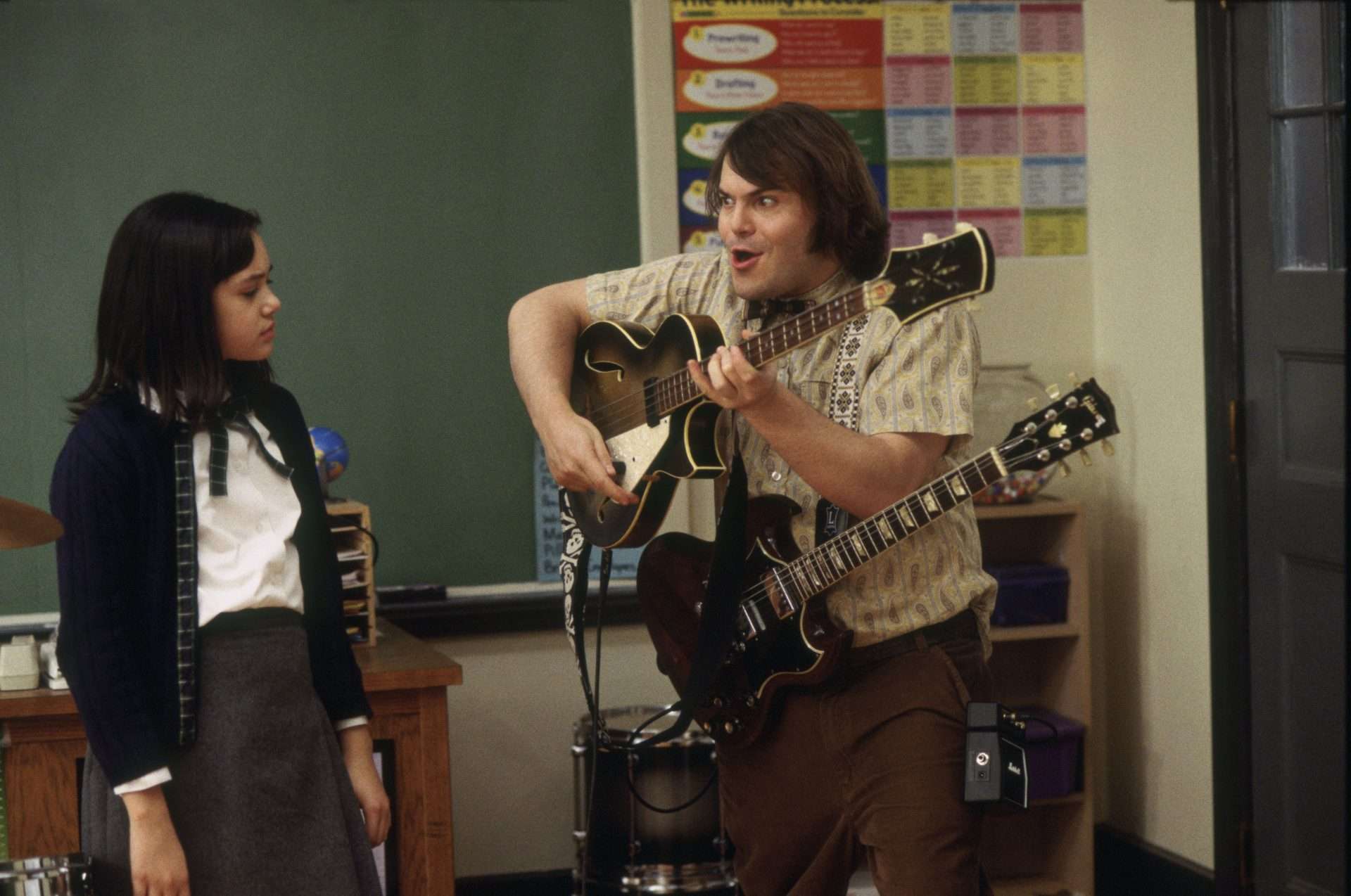

7. School of Rock (2003)

The one Linklater everybody has seen, School of Rock, is anything but the commercial sell-out it may initially appear to be. Instead, this broad comedy is a raucous delight built on the strength of Jack Black’s charisma, Mike White’s acerbic screenplay, and a dozen or so of the strongest child performances ever committed to celluloid. It is one of the very few comedies that are willing to address childhood beyond sentimental cliche, showing the students as feisty and conflicted characters who have their own agency beyond the charismatic whims of Black’s Dewey Finn, the layabout musician who becomes the unlikely savior of these uninspired 5th graders.

And that’s before we get to the songs, some of the most joyous expressions of a basic musical experience I can remember. The collaboration between the different performers and filmmakers reflects the musicians riffing off of each other, performing songs penned by The Mooney Suzuki. As a viewer, you are put in the thrilling dual position of a de facto audience member loving the music and film viewer engaged with how the various threads are being tied together. A skillfully crafted and lovingly made comedy for all ages, School of Rock deserves its classic status.

6. Last Flag Flying (2017)

Last Flag Flying can’t lay claim to any sort of classic status. It came and went largely without incident in 2017, but in hindsight, we all missed a trick in not praising this as one of the best of the year. Steve Carrell, Bryan Cranston, and Laurence Fishburne are a trio of Vietnam vets, reunited by their desire to desire to give Doc’s (Carrell’s) son a worthy send-off after dying in service in Iraq. The film adapts and updates the classic New Hollywood film The Last Detail, showing how that film’s timeless anti-war mentality has grown with the disillusionment many Americans feel towards their country’s involvement in the Middle East. The main characters have sacrificed it all for their nation, suffered the consequences, and have received next to nothing in return.

Despite that somber reading, Last Flag Flying is a lot of fun in its own way. The chemistry between the performers is on point (this may be the best dramatic role of Carrell’s career), and structuring the script as a road movie is an ideal vessel for the rat-a-tat dialogue Linklater specializes in capturing. The transitions between the relaxed tone and scenes of serious dramatic weight are beautifully handled and cement Last Flag Flying as one of the most thorough and compelling films about the Iraq War by any filmmaker.

5. Dazed and Confused (1993)

Linklater’s commercial breakthrough is an epoch in 1990s cinema, a film that broke into the mainstream without major stars or a clear narrative structure. It all unfolds in one night when schools are out for summer in 1970s Austin, a riff on another New Hollywood classic, American Graffiti. But whereas Lucas’s film documented a bygone Americana, Dazed and Confused doesn’t bathe in its period setting despite the obviously meticulous attention to detail. The world feels lived in, so the characters feel more developed, allowing an ensemble of talented teens (including some future stars) to let loose with fun dialogue and surprising plot developments that conform to coming-of-age tropes without ever feeling tired.

Slacker portrayed a similar youth culture in a seamlessly naturalistic way, and in that sense, Dazed and Confused two years later represents a leaping point for Linklater as director. It is a more mainstream film with more conventional humor, hence its success on home video. Still, it is unmistakably a Richard Linklater film with dry humor and a fascination with the passage of time. The movie’s most famous quote (delivered by then-unknown Matthew McConaughey), “I get older, they stay the same age,” is a crude joke about high school girls but also reveals some of the artifice of the coming-of-age genre which Linklater attempts to peel away. Dazed and Confused portrays a fun night on the town with your friends but ends with an acknowledgment that all good things must end.

4. Waking Life (2001)

In the 2000s, Linklater began experimenting with rotoscoping, in which live-action footage is traced over so as to make the trippy tableaus of Waking Life technically comprise his first animated film. The film is largely plotless. In fact, it contains a protagonist so ethereal that he does not experience “scenes” in his own life. He simply flits between them without meaning in a liminal space between dreams and lucidity. Along the way, he encounters several figures who pose philosophical questions on the nature of life and dreams. Highlights include Caveh Zahedi (a real-life documentarian) reciting Bazin’s theory on the holiness of cinema and a return to the screen for Celine and Jesse of the Before trilogy.

Waking Life was not a hit for mainstream audiences, but there’s plenty to chew on for the more cerebral viewer and dedicated Linklater fans. Critics have noted similarities between this and Slacker, the director’s first widely available feature, and indeed the structure is similar. With advanced technology and more of a budget, this is the work of a filmmaker who is able to take a more expansive and experimental approach to the themes that interest him. It’s the work of a free man, a rare thing in the studio system, and a riveting archive of various thoughts and images that collide in a way that really inspires the creative mind.

3. Boyhood (2014)

Linklater received the best reviews of his career for Boyhood, a film whose behind-the-scenes gimmick perfectly complements its themes of aging and the seemingly random but remarkable vicissitudes of existence. As you probably know, the movie was made over 12 years and depicts a young man (played by Ellar Coltrane) from a child of 6 to a college-bound young man across various scenarios that explore how the smallest of moments influence our greatest decisions. Particularly potent is his relationship with his mother, played by Patricia Arquette, who won a deserved Oscar for her role as a determined woman overcoming hardship to provide for her children. Frequent Linklater collaborator Ethan Hawke is similarly sterling as the father, empathetic and affable, but also clearly someone who prioritizes his own wellbeing above his child’s.

In shooting for something so intensely personal and ostensibly mundane, Linklater arrives at something universal. A decade after Boyhood’s release and its overwhelming acclaim, you can appreciate the film beyond its gimmick. The gimmick is essential to the message, of course, but the themes of aging and the complexity of human relationships are simply an extension of his previous work. The themes work because they’re relatable, timeless, and seamlessly woven with Linklater’s light touch as director. In hindsight, this should’ve won even more Oscars.

2. Slacker (1990)

Slacker is far rougher around the edges than the films that precede it on this list, but in its own little way, it was a revolution upon its 1990 release. A year after Soderbergh won the Palme d’Or for Sex, Lies, and Videotape, Linklater planted his foot down as the next new face of American independent cinema with a film that is truly just that – independent. I mean this financially – there was no Miramax money in this, costing a measly $20,000 – and artistically, as there’s still nothing in the Linklater catalog quite as effortless and unorthodox as Slacker. In Austin, Texas, several junkies, hipsters, and misfits amble around the streets and engage in their daily routines… and that’s about it. Rather than trying to glean a concrete meaning from these images, Linklater allows you to observe, turning a passive act of film viewing into an active one.

In 2024, Slacker can be seen as something of an archival marvel; it is in the National Film Registry, after all. A stroll around city centers nowadays will reveal a perhaps less charming vision of modern life, meaning Linklater’s film is a touching chronicle of the loafing of yesteryear. It’s a crystal clear distillation of his driving idea as a filmmaker: the most important truths can be revealed in the idlest of moments. Nobody shoots dialogue and captures the minutiae of eccentric behavior quite like Linklater. It is an inspiring thought that Linklater shot this with friends for a pittance and soon scaled the studio system. Slacker still stands tall as an iconic and hilarious snapshot of a point in time for Austin, Texas, and its most creative residents.

1. Before Trilogy (1995, 2004, 2013)

Yes, it’s a cop-out of sorts. Everybody has a different answer for their favorite movie in the Before trilogy. Do they favor the swooning attraction of Before Sunrise (1995), the melancholic reunion of Sunset (2004), or the middle-aged milieu of Midnight (2013)? In three films over 18 years, Linklater and actors Ethan Hawke and Julie Delpy (who co-wrote the latter two screenplays) created one of cinema’s most enduring and authentic love stories with the story of Celine and Jessie, soulmates who time cannot separate.

Each installment in the trilogy picks up a day after the last and, in typical Linklater fashion, follows a single day. In Sunrise, they are complete strangers who hop off a train in Vienna together and spend a magical night filled with adorable flirting and beautifully realized emotional revelations. Nine years later, they reunite in Paris. Hawke’s character is now a writer who has based a popular novel on their night together.

Read More: 10 Best Movies to Watch for True Fans of Richard Linklater’s

The subsequent two films will explore the complexity of Jesse using his real experiences for his art, as well as the increasing difficulty of justifying their relationship’s more immoral aspects. Before Midnight may be my personal favorite, laden with arguments in which you can feel Hawke and Delpy channeling their own feelings in marriage and with each other’s characters come to the fore. It also gestures towards the generation younger than Celine and Jesse, with side characters who fell in love in similar circumstances over Skype, a flirtation with the modern for a love story that seems so archaic on paper.

In summation, the films are Linklater’s most outstanding achievement as a creative. It is hard to think of arthouse films that are more immediately lovely and involving, readily recommendable to anyone and everyone. Hawke and Delpy’s charm and chemistry, the scenic European locations, and the subtle editing emphasize each new beat that comes between the central duo. There’s so much to love and boundless creativity to dive into if you’ve somehow never had the pleasure.