The stage is set, the electorate is ready, and the script is being written. But what hidden forces guide their hands as they press the blazing blue button to shape the nation’s destiny?

Beyond the socio-economic realities that influence a voter’s perspective, Indian cinema stands out for its undeniable impact on the country’s political consciousness. While not always a direct civics lesson or overt propaganda, Indian films still possess a remarkable ability to spark a political awakening in a person, blatantly or through subtle, nuanced narratives.

For a generation untouched by the direct struggles against British rule or other external oppressions, the earliest and the most influential source of nationalism often emerged from the youngest art form: cinema.

Iconic films like “Mother India,” “Hum Hindustani,” “Haqeeqat,” “Border,” “Lagaan,” and “Swades” have portrayed powerful narratives of sacrifice, resilience, pride, and heroism in service of the nation, which has instilled a sense of political identity in many of us.

Use of Cinema for Politics

This profound connection between cinema and nationalism didn’t go unnoticed by political entities. Time and again, films have acted as a ‘friend’ to political parties, glorifying their ideologies, policies, and agendas while almost always failing to be honest with either fact or fiction.

The origin of films being used for propaganda can be traced back to 1915 with D.W. Griffith’s ‘Birth of a Nation’ — a three-hour artistic marvel of its time. While it made history by becoming the first film to be screened at the White House, it was also considered a “Lost Cause” propaganda piece, seeking to transform the image of the Ku Klux Klan from racists to heroes.

Hollywood continued its dance with propaganda with films like Hearts of the World (1918), designed to convince Americans to enter WWI, and Leni Riefenstahl’s German documentaries Triumph of the Will (1935) and Olympia (1936), promoted the Nazi agenda with chilling efficiency.

In India, as the young independent nation romanticized the end of the freedom struggle, the Nehruvian era of the 1950s saw a surge in films steeped in socialism and national awakening. Titles like Anand Math (1952), Jagriti (1954), C.I.D. (1956), Do Aankhen Barah Haath (1957), Ab Dilli Dur Nahi (1957), and Hum Dono (1961) focused on a united and progressive India.

In later decades, even when the theme was war, as in Haqeeqat (1964), or patriotism, as in Manoj Kumar’s trilogy — Upkaar (1967), Purab aur Paschim (1970), and Kranti (1981) — the films conveyed a strong message of national pride and unity. Some films broke the mold to interrogate the system and inspire political action. Movies like Do Bigha Zamin (1953), Awaara (1951), Pyaasa (1957), and Kissa Kursi Ka (1977) boldly highlighted social and economic inequalities, setting a precedent for socially conscious cinema. In the 1980s and 90s, films like Jaane Bhi Do Yaaro (1983), Albert Pinto Ko Gussa Kyoon Aata Hai (1980), and Khal Nayak (1993) used humor and satire to critique political corruption and bureaucratic inefficiencies.

Politicization of Indian Cinema Post-2014

The political landscape of India has undergone a significant transformation since 2014, and Indian cinema has followed suit. We have been oscillating between boycott calls, censorship, and tax-free tickets.

Films like The Kashmir Files, The Kerala Story, and Uri: The Surgical Strike have served up nationalism on a saffron platter, while others like Toilet: Ek Prem Katha (Swachh Bharat Abhiyaan), Padman, Mission Mangal, and hilariously, even a section of Animal (championing Atmanirbhar Bharat through the absurdity of a deadly weapon) have acted as celluloid cheerleaders for government policies and achievements.

Political biopics have flooded the screens, too, with films like “The Accidental Prime Minister,” “Thackeray,” “Mai Atal Hu,” and “NTR: Kathanayakudu” attempting to humanize certain political leaders while portraying others in a poor light.

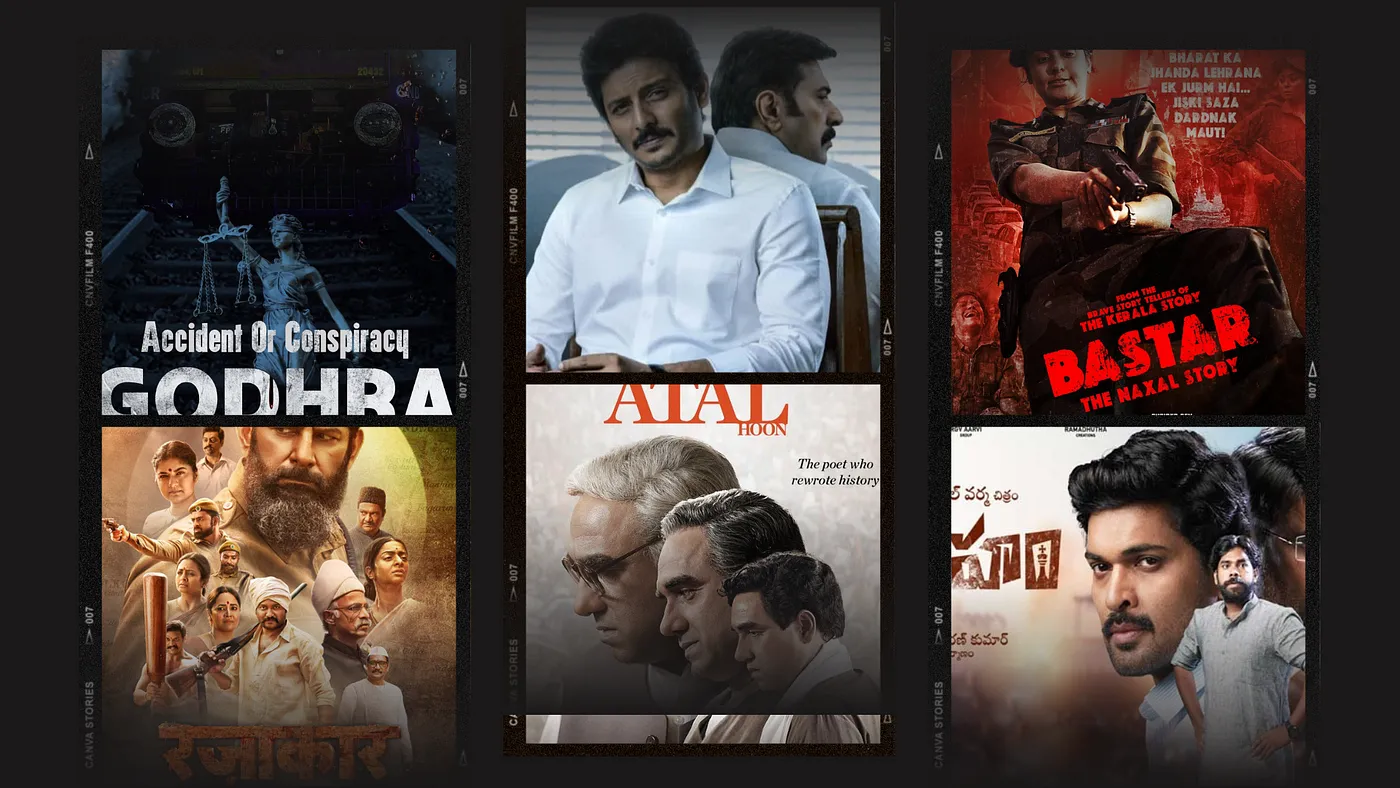

This election year, theatres were in a perpetual state of déjà vu — campaign films masquerading as entertainment. Over ten films in different languages aimed to sway voter sentiments. Titles like Article 370, Bastar — The Naxal Story, Swatantrya Veer Savarkar, The Vaccine War, Vyooham, JNU: Jahangir National University, Yatra 2, Razakar: The Silent Genocide of Hyderabad, Accident or Conspiracy: Godhra, Rajadhaani Files, and Vivekam dominated the screens. Some of these films received public endorsements from political leaders, including the Prime Minister.

This trend raises critical questions about the role of cinema in shaping future political discourse and the extent to which we, as consumers of cinema, allow it to influence our minds. In a nation where political elements can use our democratic strength against us, there are only a few unifying forces as powerful as cinema.

The movie theater is a shared space where we momentarily set aside our differences to become part of something greater than ourselves: the audience. Believed to be far more tolerant and reasonable than a directionless mob, we, as the audience, have a responsibility and the power to discern the narrative. We must critically evaluate the messages we’re fed and demand more from the stories we tell.

For, in the darkness of the movie theater, we find a shared humanity that needs to be protected. It can either be manipulated or empowered — the choice is ours.